-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2017; 7(2): 87-91

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20170702.08

Prevalence of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children with Idiopathic Epilepsy at Assiut Children University Hospital

Eman Fathalla Gad1, Azza Ahmed El-tayeb1, Islam Shabaan2

1Department of Pediatrics, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt

2Department of Psychiatry, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt

Correspondence to: Eman Fathalla Gad, Department of Pediatrics, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopment disorder affecting approximately 5%–7% of children worldwide. Many studies have shown that there is an increased prevalence of ADHD in children with epilepsy. Objectives: To determine the prevalence of ADHD and its associations in children with idiopathic epilepsy in Assiut University children hospital. Methods: A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at Assiut University children hospital from October 2015 to October 2016. Our patients aged from 3 to 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy for at least 1 year were recruited into the study. Data were collected using a pre-tested interviewer administered questionnaire. ADHD was defined using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria. Chi-square test and multiple logistic regressions were used in the analysis. Results: This study included 120 children. 90 patients were males and 30 patients were female. 85 patients had generalized epileptic seizures and 35 patients had partial epileptic seizures. 35 (29%) patients had ADHD. Partial epileptic seizure type; duration of epilepsy over 2 years and uses of more than one anti-epileptic drug was significantly associated with increased risk of having ADHD. Having partial epileptic seizures and use of more than one antiepileptic agent were independent predictors for the development of ADHD in multiple logistic regression. Conclusions: More than 29% of epileptic children in this study had associated ADHD. Partial epileptic seizure type, duration of epilepsy over 2 years and use of more than one antiepileptic drug were significantly associated with ADHD.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Seizure, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD and children

Cite this paper: Eman Fathalla Gad, Azza Ahmed El-tayeb, Islam Shabaan, Prevalence of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children with Idiopathic Epilepsy at Assiut Children University Hospital, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 87-91. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20170702.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder associated with at least six symptoms of inattention and/or at least six symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity. Symptoms must be severe enough to interfere with functioning, must occur in at least two settings (i.e., school and home), and must have an age of onset before 12 years of age [1]. Diagnoses can be specified as a predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/ impulsive, or combined presentation. ADHD has a prevalence about 7%–9% of children and 2.5%–4% of adults [2, 3]. Many studies reported various prevalence rates in school-aged children. Farahat et al., in Egypt, Pineda et al., in Colombia, Pastura et al., in Brazil, and Sanchez et al., in Panama, have reported general prevalence of ADHD 6.9%, 16.4%, 8.6% and 7.4% respectively [4-7]. The prevalence of ADHD among elementary school children in Assiut City, 3rd grade was about 6% [8]. Epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were reported to co-occur at rates higher than expected for coincidental findings [9]. Population studies suggest that the prevalence of ADHD in patients with childhood epilepsy is between 12 and 17%. Several factors may account for this finding. These include common genetic propensity, noradrenergic system dysregulation, subclinical epileptiform discharges, seizures, antiepileptic drug effects and psychosocial factors [10]. Aim of work: To determine the prevalence of ADHD and its associations in children with idiopathic epilepsy in Assiut University children hospital.

2. Patients and Methods

- A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted inpediatric neurology clinic at Assiut University children hospital from October 2015 to October 2016. The ethical clearance was taken from the ethical review committee, Faculty of Medicine Assiut University. During the period of one year consecutive patients were recruited in to the study until a sample size of 120 is achieved. Our patients aged over 3 years with a confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy for at least 1 year were recruited into the study. Lower cut off age of 3 years was used, as it was difficult to diagnose ADHD before this age. Patients with cerebral palsy, degenerative disease and global developmental delay were excluded from the study as, they were well known confounding factors associated with ADHD [11]. Parents/caretakers were informed about the details of the study and written consent was obtained before recruiting their children into the study. We took all informations for the study (e.g. confirmed diagnosis, EEG findings, Drug treatment and response etc). Data were collected using pre-tested interviewer- administered questionnaire. Questionnaire contained questions on age & sex of children, duration and type of epilepsy, EEG abnormalities, current treatment and questions to assess ADHD. ADHD was defined using DSM-IV diagnostic criteria [12]. Seizures were classified using international classification of epileptic seizures [13]. Data were entered in to worksheet in Microsoft Excel and were analyzed using computer package SPSS 16.0 for windows. Chi square test and multiple logistic regressions were used in the analysis.

3. Results

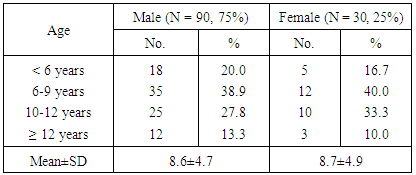

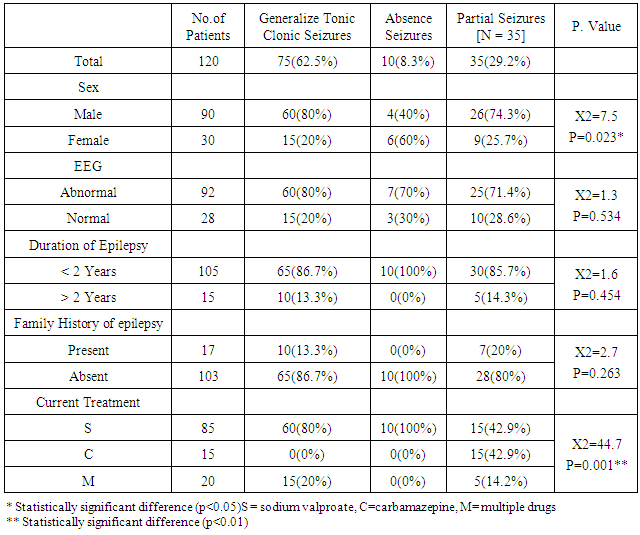

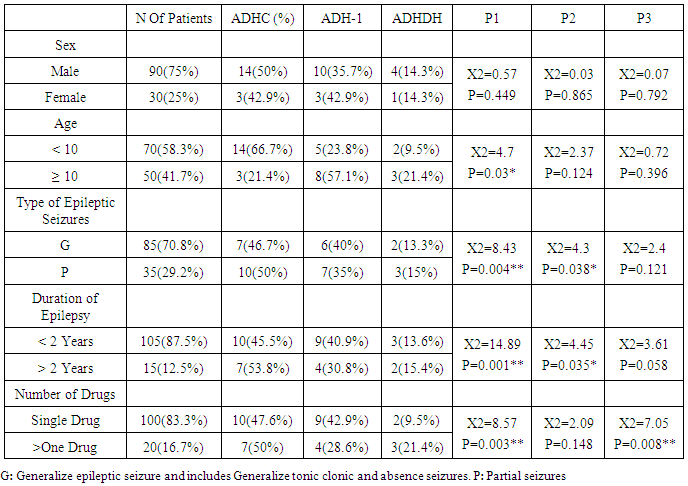

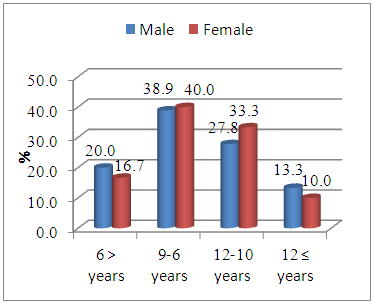

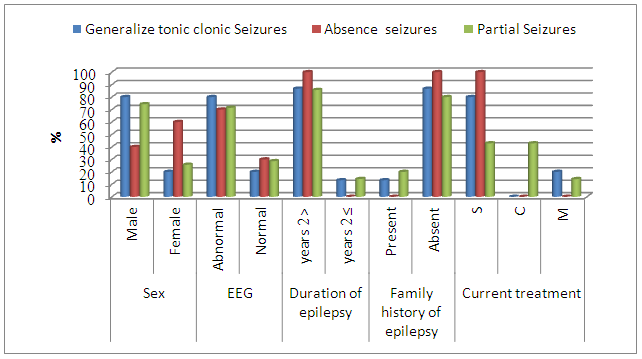

- This study included 120 children. 90 patients were males and 30 patients were female Distribution of age is shown in (table 1).In (table 2) we found that 85 patients had generalized epileptic seizure of whom 75 had generalized tonic-clonic seizures and 10 had absence seizures. 35 patients had partial epileptic seizures. Clinical characteristics of different seizure types are shown in (table 2). In (table 3) we found that thirty-five (29%) patients had ADHD spectrum disorders. 17 patients (14.1%) had ADHD combine type (ADHD-C), 13 (10.8%) had predominantly inattentive type (ADHD-I and 5 (4.1%) had predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type (ADHD-H). Associations between sub types of ADHD with sex, age categorytype of epileptic seizures, duration of epilepsy, current treatment and response to treatment is shown in (table 3).

|

| Figure 1. Age Distribution of the Study Population |

|

| Figure 2. Clinical Characteristic of Different Epileptic Seizure Types |

|

4. Discussion

- In our study there is high prevalence (29%) of ADHD symptoms compared to general population normative values (3-5%). The prevalence of ADHD in our sample is quite similar to that reported by Dunn & Kronenberge and they recorded that the prevalence of ADHD as high as 20%–40% [14]. Although other recent studies suggest that the difference might not be so large, it is still significantly greater than general population estimates [15, 16]. The reverse is also true, in that 2.3% of children with ADHD have epilepsy [16]. Which is higher than general population rates. In our study the combined type of ADHD is most common followed by inattentive type and lastly the hyperactive impulsive. Other studies recorded that the inattentive presentation of ADHD appears to be the most common in the epilepsy population [17, 18], although other studies suggest that, as in the general population, the combined type is most common [19, 16]. The prevalence of ADHD in our sample is quite similar to that reported by [20, 21]. We found significant correlation between ADHD (combined and hyperactive-impulsive subtype) and partial epileptic seizure type. This is different to the finding of Hempel and coworkers who noted that children with intractable generalized seizures were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD [22]. Our sample differs in that we did not have a separate group of intractable epilepsy. Further Elisabeth and coworkers found that children with ADHD inattention sub type were more likely to have localization related epilepsy than generalized epilepsy [23]. It is known fact that patients with partial epileptic seizure type are having increased incidence of structural brain lesions compared to patients with generalized epilepsy [24]. Furthermore structural brain pathology is a recognized aetiological factor contributing towards the development of ADHD [24]. Our data suggests that the ADHD symptoms are significantly higher in patients who had epilepsy for more than 2 years. This may be due to chronic effects of seizures or prolonged use of antiepileptic drugs. Wei and Kelly, found associations between prolonged use of sodium valproate and ADHD [25]. Further in our study, we found that use of more than one antiepileptic drug was significantly associated with ADHD. This is supported by the finding of Williams and coworkers, who noted that children on polytherapy had verbal and visual significantly lower memory scores than children on monotherapy [26]. Without information on duration of exposure and dosage or blood levels, it is not possible to make any conclusions on antiepileptic drugs and symptoms of ADHD. In most psychiatric samples, ADHD was more common in males and is most often the combined type. Those results were similar to our findings showing that ADHD is significantly higher in males and is most often the combined type. This raises the question of etiological similarities causing both ADHD and epilepsy. Several possible explanations can be made for the association between ADHD symptoms and epilepsy. These might be neurological dysfunction, seizure variables, medication effects or psychosocial response to epilepsy. Male to female ratios were similar to the figures commonly reported for this syndrome [overall prevalence of current DSM-IV-like ADHD was 9.2% with a male: female ratio of 2.28:1] [27]. The Number of males was three times as great as the number of females (3:1) in our study. The male to female ratios for the Hyperactive (4:1) and combined (4.7:1) subtypes were also similar to ratios reported in the literature. With the inattentive subtype, the male to female ratio (3.3:1) was lower than that observed for the other subtypes. The predominance of Combined ADHD has been reported in other countries [28]. Furthermore, boys were three times more likely to develop ADHD, especially in the Combined or hyperactive/impulsive subtypes. These data are consistent with the male predominance (70%) reported for 88 hyperactive/ impulsive ADHD patients in the US [29]. In Greece, the estimated prevalence of ADHD was 8% for boys and 3.8% for girls [30].

5. Conclusions

- There is high prevalence of ADHD is seen among the children with epilepsy in our study. Partial epileptic seizure type, duration of epilepsy over 2 years and use of more than one anti-epileptic drug were significantly associated with increased risk of having a disorder in the ADHD spectrum. Having partial epileptic seizures and use of more than one antiepileptic agent were independent risk factors for the development of ADHD spectrum disorders in epileptic children.

6. Recommendations

- Further large study on large number of children with epilepsy to detect the prevalence of ADHD among epileptic and to detect the nature of the comorbidity of these two conditions. Because ADHD is a treatable behavioral syndrome with effective pharmacological and behavioral therapies, a large number of children with epilepsy might potentially benefit from screening and medical intervention. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of ADHD medication treatment both in healthy children and in Child with epilepsy. The importance of consideration for ADHD treatment was recently highlighted again by a large population. Further study to assess the effect of treatment of ADHD on epileptic patients is recommended.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML