-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2017; 7(2): 67-73

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20170702.05

Prevalence of Bronchial Asthma in Primary School Children

Alaa-Eldin A. Hassan1, Sabah Abdou Hagrass2

1Pediatric Department, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt

2Community Health, Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

Correspondence to: Alaa-Eldin A. Hassan, Pediatric Department, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

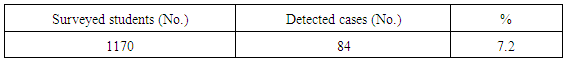

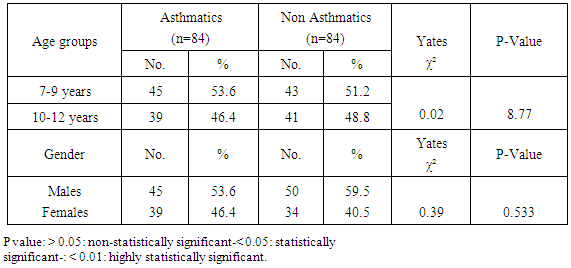

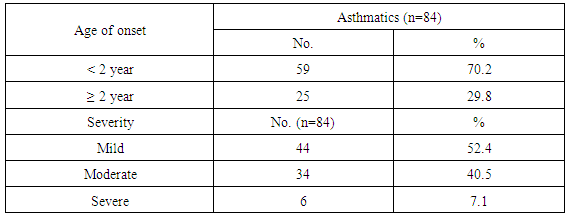

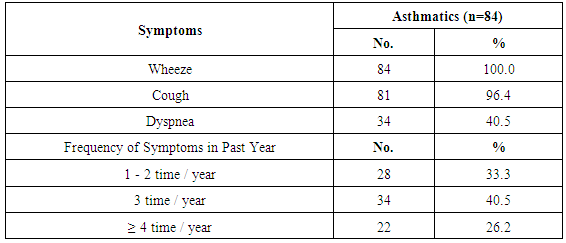

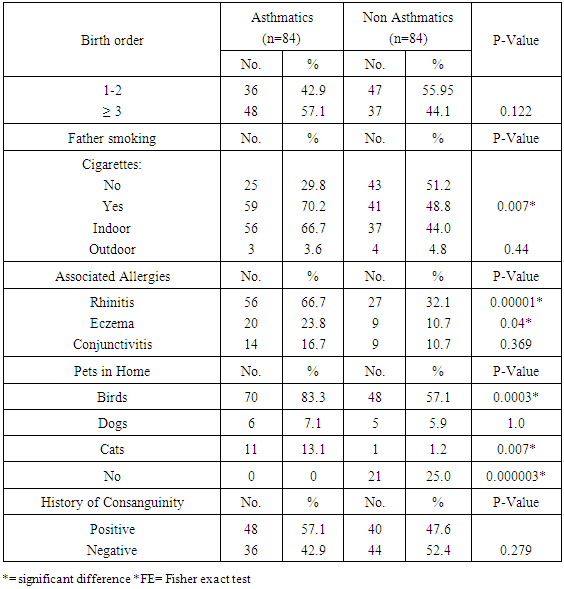

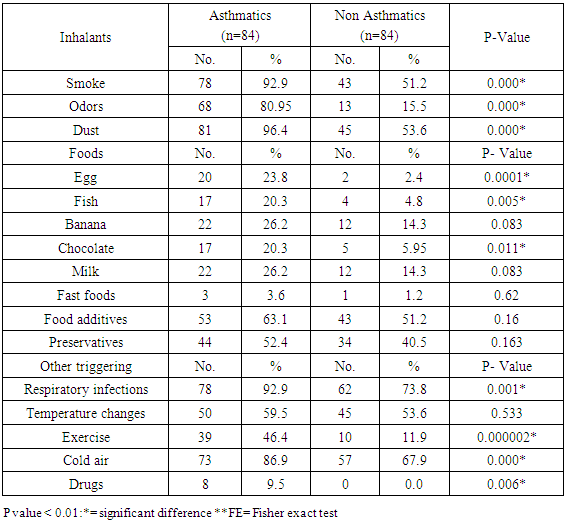

Background: Asthma in childhood is strongly associated with allergy, especially in developed countries. Common exposures such as tobacco smoke, air pollution, and respiratory infections may trigger symptoms and contribute to the morbidity and occasional mortality. Asthma is a highly prevalent chronic respiratory disease affecting 300 million people world-wide. Aim of the work: The aim of this study is to assess prevalence of bronchial asthma among primary school children and identify associated symptoms and its risk factors. Patients and methods: The present study was conducted in among 1170 children in primary schools in Assiut City in Upper Egypt. All children had inclusion criteria of age between 6-12 of primary school children. Data were collected by two questionnaires. Screening was done at two (2) steps. First step screening: children were screened for chest symptoms. The questionnaire was given to 1300 pupils, the number of pupils who respond to us were 1170 and those pupils become the screened number for our study, the age of those children range between 6-12 years old and the number of girls were 40.5% and the number of boys were 59.5%. Second step screening: All children who selected from first step screening who reported specified respiratory and asthmatic symptoms were selected and assessed individually for the second step questionnaire, as the numbers of those children were 84 children. For every diagnosed asthmatic child, we selected randomly a normal child from the pupils list inside each class. The questionnaire filled by the researcher inside the classes to have total number of 168 pupils. Results: Among asthmatic students males constituted 53.6% and females 46.4%. The prevalence of asthma among the studied students was 7.2%. Asthma was not significantly associated with age and gender. The prominent symptoms of asthma were wheeze 100%, cough 96.4% and dyspnea 40.5%. In our study 70.2% of children with asthma begun wheezing before 2 years age. The severity of asthma among studied children was mild asthma in 52.4%, moderate asthma in 40.5% and severe form of asthma in 7.1% as the frequency of attacks in past year was 1-2 times / year 33.3%, 3 times / year 40.5% and more than 4 times / year in 26.2%. The impact of symptoms on health among studied school children 100% of nocturnal awaking, 96.4% of emergency room visits and 66.7% of hospital admission. There was non-significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to low weight for age (<5th percentile) and height for age. There was significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to normal weight for age (5th –95th percentile) and overweight for age (>95th percentile). This study revealed that the presence of one type or more of other allergic disease (skin 23.8%, nasal 66.7% and eye 16.7%) was significantly associated with asthma (p = 0.000). History of asthma and other allergic conditions in the family was significantly associated with asthma in the studied children (p = 0.000). Using logistic regression analysis: a positive family history of allergy and the presence of other one or more allergic diseases were significantly associated risk factors for asthma. The triggering factors incriminated most for the attacks were dust (96.4%), smoke (92.9%), odors (80.9%) cold air (86.9%) drugs (9.5%), temperature changes (59.5%). Upper respiratory tract infections were the precipitating factor in more than two thirds of the studied children (92.9%). Exercise as a triggering factor of asthma occurred in 46.4% of the studied children in this study and has been reported in about 11.9% of the general healthy children. There was significant association between asthma and presence of family pets in the home as birds (83.3%), dogs (7.1%) and cats (13.1%). In this study there was significant association between asthma and family size.

Keywords: Bronchial asthma prevalence, Risk factors

Cite this paper: Alaa-Eldin A. Hassan, Sabah Abdou Hagrass, Prevalence of Bronchial Asthma in Primary School Children, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 67-73. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20170702.05.

1. Introduction

- According to the last edition of GINA asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation. It is defined by the history of respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation. This definition was reached by consensus, based on consideration of the characteristics that are typical of asthma and that distinguish it from other respiratory conditions [1] (GINA, 2014). Asthma in childhood is strongly associated with allergy, especially in developed countries. Common exposures such as tobacco smoke, air pollution, and respiratory infections may trigger symptoms and contribute to the morbidity and occasional mortality. Asthma is a highly prevalent chronic respiratory disease affecting 300 million people world-wide [2] (Dougherty and Fahy, 2009). Asthma is by far the most common of all chronic diseases of childhood and estimates from developed countries suggest that it affects between 11 and 20% of all school age children [3] (Godfrey, 1992). The prevalence of asthma and allergies is increasing in both western and developing countries. The prevalence of asthma among Egyptian children aged 3 - 15 years was estimated to be 8.2% [4] (El-Hefny, 1994). Despite a large volume of clinical and epidemiological researches within affected populations, the etiology and risk factors of these conditions remains poorly understood [5] (Hill et al., 1989).Aim of the work: The aim of this study is to assess prevalence of bronchial asthma among primary school children and identify associated symptoms and the risk factors affecting the development of the disease and determine the effect of asthma on general health of the children.

2. Patients and Methods

- The present study was conducted in among 1170 children in primary schools in Assiut City in Upper Egypt. All children had inclusion criteria of age between 6-12 of primary school children. Children with one or more of the following criteria were excluded from the study: children aged <6 years and >12 years, and children with chronic illness: heart diseases, chronic liver diseases, chronic renal diseases and chest diseases other than asthma. Participants were selected from the first grade as a representative sample. All schools in the city were mixed schools for boys and girls. From each school only one class in each age group was selected randomly. Total coverage of the students in the first grade was done to have a total of 1170 students. Data were collected by two questionnaires. The first questionnaire was in Arabic language while the second was self-administered questionnaire in English language which was filled by the researcher inside the classes. Screening: Screening was done at two (2) steps. First step screening: children were screened for chest symptoms by a questionnaire during the period from November 2015-December 2016. The questionnaire was in Arabic language comprising many questions. It was developed especially for the purpose of this survey. The questionnaire thought to uncover symptoms rather than diagnosis, and the term asthma was not used. The key question was "Has your child ever had attacks of wheezy chest ". There were also three supplementary questions about recurrent nocturnal cough, sudden shortness of breath and wheezing, shortness of breath or cough on exertion. The first questionnaire included the following variables:Personal history including: name, sex, age and residence of the school child, recurrent cough especially at night, wheeze, dyspnea or cough on exercise, there allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis or dermatitis, and there any member of the family suffering from allergic rhinitis or conjunctivitis or dermatitis. The questionnaire was given to 1300 pupils, the number of pupils who respond to us were 1170 and those pupils become the screened number for our study, the age of those children range between 6-12 years old and the number of girls were 40.5% and the number of boys were 59.5%. Second step screening: All children who selected from first step screening who reported specified respiratory and asthmatic symptoms were selected and assessed individually for the second step questionnaire, as the number of those children were 84 child. For every diagnosed asthmatic child, we selected randomly a normal child from the pupils list inside each class. The questionnaire filled by the researcher inside the classes. The second questionnaire included the following variables: Personal history including: name, sex, age and residence of the school child, clinical history including: symptoms of asthma (recurrent cough, wheeze, dyspnea), age of onset of the symptoms, severity of the disease (mild, moderate, severe), frequency of the symptoms, associated allergic conditions in the child (eczema, rhinitis, conjunctivitis), medications of asthma including (B2 agoist–Glucocorticosteroids – Methylxanthines- Anticholinergics- Cromolyn Na-Ketotifen- leukotriene antagonist), impact of symptoms (nocturnal awaking - emergency room visits -hospital admission - missed school days), history about risk factors (respiratory infections - dust –smoke –exercise – odors – drugs –cold air – change in temperature), food allergy to specific type of food (egg –banana- fish –milk)-usage of food additives fast food - canned food, family history of consanguinity, family size, occupation of the father and whether the father is a smoker, if yes the smoking is indoor or outdoor). The presence of allergic manifestations in any family member including; asthma, nasal allergy, dermal allergy, or conjunctival allergy, history of housing: number of rooms, number of persons in bedroom, sharing in patients bed and presence and type of family pets (dogs, cats, birds and others), in addition to the questionnaire, all children were subjected to full clinical and physical examination and anthropometric measurements.Criteria of diagnosis of asthma: the diagnosis of asthma is based primarily on history and physical examination. The clinical features a patient exhibits, particularly the symptoms he complains of and the signs noted on physical examination, are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis of asthma: the characteristic symptoms of asthma are cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. Wheezing is the most common symptoms of asthma. Physical examination of the respiratory system may reveal no apparently abnormality if the patient is not in asthmatic attack. Wheezing predominantly occurs on exhalation. If the child has physician-diagnosed asthma (documented clinical professional diagnosis, follow-up school clinic cards, health insurance cards), the child is on regular asthma medications.Statistical analysis: data were analyzed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) software package version 16. The data, categorical variables, were expressed as frequency and percent and the comparison between these variables was carried out using Yates chi square (2) test or Fischer exact test as appropriate. The level of significance was adjusted at P value < 0.05. Presentation of the collected data in tables and figures. Finalization of the study research including final reviewing of liter-ature, discussion of the results, conclusions and recommendations, summary, and references of the study.

3. Results

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Worldwide, the prevalence of asthma among children has increased steadily during the last two decades. Considerable evidence indicates that there is a significant regional variation in the prevalence of asthma and in the relative weight of risk factors [6]. Few studies evaluated asthma prevalence in Egypt. In a survey including 115 health centers in five governorates, (Khallaf et al., 1993), [7] reported that asthma prevalence was 4.8% in Egypt. (El-Hefny, 1994), [4] found that asthma prevalence was 8.2%, using a questionnaire among 13028 children 3-15 years old. (Georgy et al., 2006) [8] used translated and adapted version of the ISAAC questionnaire which was distributed to a sample of 2645 person, 11-15 years old school children in Cairo. They revealed that wheeze during the last year was 14.7% and physician diagnosed asthma was 9.4%. (Clark et al, 2010), [9] reported that prevalence of asthma in Canada among 3482 studied children aged 3-5 years was 9%. (Abdalah et al., 2012), [10] reported that prevalence of asthma in Assuit among 1048 in primary school children was 6.2%. In our study, the prevalence of asthma was 7.2% among primary school children in Assiut city by using a questionnaire among 1170 pupils. This rate is more than what has been previously estimated in Assuit in 2012 (Abdalah et al., 2012), [10]. This may be due to increase exposure to risk factors and use of fast foods and food additives. Otherwise this rate is less than that estimated in Cairo in 2006 (Georgy et al., 2006), [8]. This may be due to the different geographical, social and environmental factors between these two localities. Cairo is mainly an urban district surrounded by multiple industrialized areas where air pollution by sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone and particulate matter is one of the highest levels worldwide due to industrialization and heavy traffic, while Assiut is a semiurban area surrounded by rural societies, and has less industrial areas (MSEA, 2001), [11]. In the Middle east, asthma prevalence (ranges from 5% - 23%) has previously been reported to be lower than in developed countries (Behbehani et al., 2000; Shohat et al., 2002; and Georgy et al., 2006), [12, 13, 8] and so these results agree with our results. In our study, although most asthmatic children were males (53.6%), the prevalence of asthma among studied children was not significantly associated with gender. (Barbee and Murphy, 1998), [14] reported that asthma was more common and more severe in boys than girls while (Landau et al., 1993), [15] found that gender difference regarding asthma prevalence were less evident after the age of 6 years. Until age 13-14 years, the incidence and prevalence of asthma are greater among boys than among girls (De Marco et al., 2000), [16]. Before age 12, boys have more severe asthma than girls, with higher rates of admission to hospital. In our study, whereas 53.6% of asthmatic children had asthma for less than 9 years, 46.4% of asthmatic children between 10-12 years, the prevalence of asthma among studied children was not significantly associated with age variable. Mannino et al., (1998), [17] reported that approximately 25% of children with persistent asthma have begun wheezing before 6 months of age and 75% by the age of 3 years. Also (Hsu et al., 2004), [18] found that 30% of their patients had their onset of symptoms before the age of 14 years. In our study approximately 70.2% of children with asthma begun wheezing before 2years age. Spergel and Paller, (2000), [19], Rosener and Virchow, (2007), [20] and Abdalla et al., (2012), [10] revealed that the prominent symptoms of asthma were dyspnea and cough (44.6% and 27.7% respectively). Besides, 58.5% of the asthmatic children had their asthma attack at night (nocturnal asthma). The mechanisms accounting for the worsening of asthma at night are not fully understood but may be driven by circadian rhythm of circulating hormones such as epinephrine, cortisol and melatonin and neural mechanisms such as cholinergic tone. An increase in airway inflammation at night has been reported. This might reflect a reduction in endogenous anti-inflammatory mechanisms (Calhoun, 2003), [21]. In our study, the prominent symptoms of asthma among studied children were wheeze 100%, cough 96.4% and dyspnea 40.5% similar to (Rosener and Virchow, 2007, [19] and Hossny et al., 2009), [22]. In our study, severity of asthma among studied children was mild asthma in 52.4%, moderate asthma in 40.5% and severe form of asthma in 7.1% as the frequency of attacks in past year was 1-2 times / year 33.3%, 3 times / year 40.5% and more than 4 times / year in 26.2%. The impact of symptoms on health among studied school children 100% of nocturnal awaking, 96.4% of emergency room visits and 66.7% of hospital admission. In our study, 100% of asthmatic cases were treated with methylxanthine and 92.9% of the cases were treated with inhaled corticosteroids. While 76.2% of asthmatic cases were treated with cromolyn Na, 70.2% of the cases were treated with leukotriene antagonist and 65.55 were treated with B2 agonist. In an attempt to determine the effect of asthma on the general health (weight and height) of the children we observe that there was no significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to low weight for age (<5th percentile). There was significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to normal weight for age (5th –95th percentile). There was significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to overweight for age (>95th percentile). There was no significant difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic group regard to height for age. This study revealed that the presence of one type or more of other allergic disease (skin 23.8%, nasal 66.7% and eye 16.7%) was significantly associated with asthma this in agreement with (Abdalla et al., 2012), [10]. In our study 66.7% of the asthmatic children had allergic rhinitis. Atopy, particularly atopic dermatitis is a significant risk factor for development and persistence of asthma in children (Wright et al., 1995, [23] and Spergel and Paller, 2003), [19]. In another study in Egypt (Hossny et al., 2009), [22] found that 53.3% of studied asthmatic children had associated allergic disease (atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis or food allergy). History of asthma and other allergic conditions in the family was significantly associated with asthma in the studied children. Our results are in agreement with (Kalyoncu et al., 1999; Zedan et al., 2009 and Abdalla et al., 2012), [24, 25, 10]. This can be explained by the fact that asthma is a syndrome influenced by genetic and environmental factors; the hereditary component has been demonstrated by (Demoly et al., 1993), [26]. Case-control and family-based association studies have mostly confirmed a link between a novel gene-ADAM33- and asthma (Holgate et al., 2006) [27]. The most common triggering factors for asthma attacks among studied students were: exposure to dust (96.4%), smoke (92.9), odors (80.9), cold air (89.9), drugs (9.5%), temperature changes (59.5%) and exposure to cigarette smoke (70.2%) and goza smoke (23.8%). (Abdalla et al., 2012) [10], revealed most common triggering factors for asthma were: exposure to house dust (84.6%), exposure to cigarette smoke (81.5%), playing and physical activity (58.5%). (Ernst et al., 1996, [28] and Surdu et al., 2006), [29], stated that exposure to allergens, particularly house dust mites is a risk factor of asthma development and exacerbation. Hence, measures to reduce exposure to house dust mites such as using mattress and pillow covers with mites impermeable characteristics are recommended. Also, bedding should be washed regularly at temperature greater than 60°C, rooms should be well ventilated and carpets (cleams) should be removed from the living areas and especially the bedrooms (Halken et al., 2003) [30]. It has been reported that tobacco smoke is the most important indoor irritant and a major precipitant of asthma symptoms in children and adults (Surdu et al., 2006 and Hossny et al., 2009), [29] and [22]. These data and ours emphasize the need for systemic, persistent effort to stop the exposure of children with asthma to environmental tobacco smoke. Upper respiratory tract infections were the precipitating factor in more than two thirds of the studied children (92.9%) similar to (Abdalla et al., 2012), [10]. Respiratory viral infections precipitated acute exacerbations of asthma and were the most common reason for hospital admissions in (Hossny et al., 2009, [22] and Zhao et al., 2002) [31]. How viruses provoke asthma is not clear, a study using a human B-cell culture system found that rhino virus-induced double-stranded RNA activates an antiviral protein kinase that can induce Ig class switching to IgE, suggesting a mechanism for viral provocation of allergy and asthma (Rager et al., 1998) [32]. (Jacoby, 2002), [33] suggested that the mechanism of virus-induced airway responsiveness is likely to be multifactorial including, impairment in the inactivation of tachykinins, virus effects on nitric oxide production, and virus-induced changes in neural control of the airway. Exercise as a triggering factor of asthma occurred in 46.4% of the studied children in this study and has been reported in about 11.9% of the general healthy children. (Abdalla et al., 2012), [10] reported exercise induced asthma in 58.5% of the cases. (Gotshall, 2002, [34]) has been reported exercise induced asthma in 70% to 90% of patients with persistent asthma and in about 10% of the general population. So they are in agreement with our results. Food allergy was noticed in the studied children as there was allergy to egg in 23.8%, fish 20.3%, banana 26.2%, chocolate 20.3% and milk 26.2%. Also the use of fast foods reported in 3.6%, food additives 63.1% and food preservatives in 53.4%. There was no significant association between them and asthma. (Tsai and Tsai, 2007), [35] concluded that consumption of sweetened beverages and eggs were associated with increased risk of respiratory symptoms and asthma. In our study, there was significant association between asthma and presence of family pets in the home as birds (83.3%), dogs (7.1%) and cats (13.1%). (Abdalla et al., 2012), [10] reported no significant association between asthma and parental educational level, mother's work, school level, crowding index and father's smoking. (Zedan et al., 2009), [25] reported no significant association between asthma and passive smoking whereas, they reported that bad housing was significantly associated with asthma. In our study, there was significant association between asthma and fathers occupation as 29.8% had manual laborer fathers, 65.5% had skilled laborer and 4.8% had fathers with high education (professional). There was significant association between asthma and family size. There was no significant association between asthma birth order and history of consanguinity. There was no significant association between asthma and room number, number of persons in bedroom and patients bed.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML