-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2016; 6(6): 186-192

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20160606.05

Drug Counterfeiting: The Situation in the Gaza Strip

Mohammed Abuiriban1, Sami El Deeb2

1Drug Control Department, Ministry of Health, Gaza, Palestine

2Institute of Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Technical University Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany

Correspondence to: Sami El Deeb, Institute of Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Technical University Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Drug counterfeiting is sharply in rise and prevalent in developed and developing countries with its severity and harmful effects on public health and economic welfare. World Health Organization, drug and regulatory authorities, international, governmental and non-governmental organizations, enforcement agencies as well as pharmaceutical manufacturers associations striving against counterfeit drugs. This article highlights the situation of drug counterfeiting in the Gaza Strip. Drug sources, the role of Health Ministry, the evaluation of drug quality, facilities and limitations are discussed. Furthermore, the factors encouraging counterfeiting of drugs in the Gaza Strip and the consequences on public health are addressed. Due to the great threats to the public health in the Gaza Strip, great cooperation is required between governments, Ministry of Health and other relevant organizations to achieve a significant progress in the fight against counterfeit.

Keywords: Counterfeit drugs, Gaza Strip, Quality control, Fake drugs

Cite this paper: Mohammed Abuiriban, Sami El Deeb, Drug Counterfeiting: The Situation in the Gaza Strip, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 186-192. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20160606.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The emergence of counterfeit drugs was first internationally established in 1985, now it's becoming a vital issue expanded universally and still growing. The World Health Organization (WHO), international and non-governmental organizations endeavouring to gather data and to inform governments about the nature and extent of counterfeiting [1]. Every Country has its own definition and specification for counterfeit drugs; but the general definition which was given by the WHO in 1992 describes a drug which is deliberately and fraudulently mislabelled with respect to identity and/or source as being counterfeit. Counterfeit drugs can be in either branded and generic products with the correct, wrong, or none ingredients, with inappropriate quantities of active ingredient or with inaccurate or fake packaging and labelling [2]. However, one should differentiate between counterfeit drug and substandard drug. The later is defined as genuine drug that has failed to pass the quality measurements and specifications set [3]. Counterfeit drugs were classified into four subclasses [4]: 1) perfect; 2) imperfect; 3) apparent; 4) criminal. These subclasses are related to five groups of counterfeiters [5]. The perfect counterfeit drugs contain correct and right amount of active and excipient ingredients which are related to imitators and smugglers counterfeiters. They are manufactured in other countries and illegally transported. The major difference is the circumvention of taxes by the smuggler group. The imperfect counterfeit drugs are related to disaggregate counterfeiters that contain right ingredients with an incorrect concentration and/or formulation resulting in defective quality specifications. The apparent counterfeit drugs are related to fraudster’s counterfeiters. These drugs are similar to the original drugs but without active ingredient and not the drug of choice for a particular disease. The criminal counterfeit drugs are related to desperadoes’ counterfeiters that do not contain active ingredients but contain harmful or toxic substances. Despite of similarity to the original drugs, the consequences on consumers can be fatal. Drug counterfeiting is dramatically increasing in number and sophistication worldwide and is affecting both developed and developing countries. In most developed countries with effective regulatory systems and market control the prevalence of counterfeit drugs is estimated by less than 1%. In contrast, numbers given for the prevalence of counterfeit drugs in many developing countries ranged from 10% to 30%. Furthermore, the European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicines (EAASAM) has indicated that over than 50% of online purchased drugs are counterfeited [6, 7]. It is not easy to obtain an accurate percentage, since the phenomenon spreads, more and more drugs are counterfeited. Estimation put counterfeit drugs at more than 10% of the global drugs market. Certainly, the developing countries take the big portion with an estimation of 25% of the drugs consumed are believed to be counterfeited. In some countries, the percentage may jump to 50% [8-10]. Counterfeit drugs are spanning a broad spectrum of drugs ranging from lifestyle to life-saving drugs, including generic drug forms [6]. In Europe, 2.7 million counterfeit drugs were detected in 2006 which were five times more than in 2005 [11]. At the same year due to a counterfeit cough syrup in Panama, 115 persons died and more were disabled [12]. In 2009 about 84 children were died in Nigeria as a result of toxic chemicals in teething drugs [13]. In Angola in 2012 the largest import counterfeit antimalarial drug was confiscated with over 1.4 million packets of this drug shipped from China [14]. Despite of its prevalence on developed countries, the most frequently counterfeit drugs are the expensive lifestyle drugs as steroids, hormones and antihistamines that are used for erectile dysfunction, hair loss and weight management. While in developing countries, the most counterfeit drugs have been those used to treat life-threatening diseases as malaria, tuberculosis, anticancer, antiviral and HIV/AIDS [8-10]. The counterfeit drug trade exceeded the illicit drug trade by around 50% and its cost to the global economy in 2010 was estimated to be about $75.5 billion [15]. This threat was continued to proliferate more and more after that; this industry is growing rapidly each year. The aforementioned examples provide reasons for concern and to raise awareness of public, healthcare providers and government agencies about the severity and danger of this global threat. It is intended to provide exact data of our region in order to support a rational global dispassion of this topic.

2. Drug Counterfeiting in the Gaza Strip

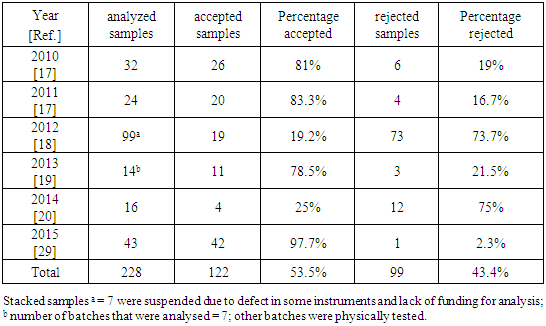

- There is little published research assessing the situation of drugs in the Gaza Strip. The overview is grounded on annual reports of General Administration of Pharmacy at the Ministry of Health (MoH) and relevant news. These reports provided little information regarding the situation of drug counterfeiting in the Gaza Strip.There are more than 4,000 drugs available in the Gaza Strip market, only around 725 drugs are produced by local pharmaceutical industry of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip [16] and only 1608 drugs are registered by the MoH [17-20]. The remaining drugs are imported from Israel, some come illegally from Egypt through tunnels.In 2009, the police in the West Bank seized the contents of more than two cosmetic and medical factories, confiscated raw materials and drugs. These factories, which had been in operation since 2005, had been manufacturing counterfeit drugs and relabeling expired drugs. Their products were sold to local markets for more than four years. The factories had obtained their materials from Israel settlements [21]. Furthermore, four tons of counterfeit drugs were seized in al-Ram in 2008, while a large number of expired drugs were seized in Nablus. These drugs included sixteen different types of cancer therapeutics and were estimated to be worth around two million USD [22]. These more efficient quality investigation procedures came after implementation of new standards by the West Bank’s MoH in 2007 to prevent stolen and counterfeit drugs from reaching pharmacy shelves. The Ministry committed to monitor drug manufacturers and ensure that pharmacists only buy drugs from licensed companies [23]. The chaos following the eruption of the second Intifada in 2000 increases the risk that counterfeit drugs enter the West Bank supply chains.Common counterfeit drugs in Israel are anti-impotence drugs and general antibiotics. In 2007, the Israel customs authority seized a shipment of counterfeit drugs from a container ship coming from China, which included more than 11,820 fake Viagra pills, 800 fake Cialis pills and several hundred other unidentified pills. It was claimed that the Palestinian authority was the final destination of the goods [24]. The Pharmaceutical Security Institute reported in top ten ranked counterfeit drugs seized/discovered in 2009, those 52 instances of counterfeit drugs found in Israel, making it the 9th highest ranking country in the world [25]. In 2012, the MoH in Israel established the Division of Enforcement and Inspection in order to carry out enforcement activities at the frequency required to eradicate manifestations that could endanger public health. One of the objectives of this division is dealing with all the various aspects of pharmaceutical crime (counterfeit and stolen medicines, drugs, counterfeit dietary supplements, etc.) [26].Other drug sources in the Gaza Strip are those drugs smuggled through Rafah tunnels on the Strip's border with Egypt and the donated drugs. Smuggling drugs continue to be a problem, as its presence remains high in the local market. Despite closing the majority of the smuggling tunnels in Egypt border in 2013, drugs are still finding their way into the Gaza Strip. Moreover, drugs are also probably reaching the Gaza Strip illegally from Egypt through the sea. In 2013, a new law regulation was approved in the Gaza Strip which making the abuse and trafficking of drugs a felony, which previously had been only a misdemeanor. The change has helped decreasing the amount of smuggled drugs. The legislative council in the Gaza Strip approved the “New Drugs and Mental Stimulants Law” in 2013. They established severe penalties with the goal of deterrence included tougher sanctions against dealers who could face the death penalty and penalizing drug users [27].Donated drugs which enter the Gaza Strip via Rafah border from Egypt are mostly transported in poor conditions. Sometimes, donors award large quantities of a particular medication which is not largely consumed by patients, other donated drugs reached close to expiry and some are labeled in foreign languages [28]. Currently, donated drugs are the main source of medications at the MoH. It represents more than 57% of the total drugs supplied to MoH in the last six years [17-20, 29].Counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip include preparations without active ingredients, toxic preparations, expired relabeled drugs, drugs issued without complete manufacturing information and drugs that are unregistered by MoH. The effects of counterfeit drugs on patients are difficult to detect, investigate and quantify and are mostly hidden in public health statistics. There are no reliable data on the mortality and morbidity resulting from the consumption of counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip.The Palestinian MoH has a limited effect in monitoring the quality of drugs available on the private market. Examples of private sector complain from drug quality are sedimentation in the bottle from Chlorohexidine gluconate which is a germicidal mouthwash that reduces bacteria in the mouth, another example is a cracked and spotted tablet of folic acid. These drugs failed to pass quality analysis test and have been withdrawn from the market. The number of samples that were taken from complains of private market to test their quality according to the MoH annual reports are summarized in Table 1. The data in table 1 shows that more than 43% of the drugs inspected from the private market complains for the past six years failed after analysis. This indicates a high prevalence of drug counterfeiting in the private market. However, this percentage may be underestimated due to the lack of random routine check from MoH. Moreover, the percentage of rejected drugs in 2012 and 2014 were higher than other years. It may be due to the smuggled drugs from Egypt in 2012 and donations of drugs after wars with Israel in 2012 and 2014.

|

|

2.1. The Center for Environmental and Occupational Health

- Analyses were carried out at this center which is located in the West Bank on a contract basis until 2008. Samples were not sent to this center in the West Bank for analysis after 2008 because of the lack of communication between the MoH in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip due to internal conflict thus worsening an already crumbling healthcare system in the Gaza Strip. Analyses at the center were limited to samples taken from drugs bought by the government, non-governmental and charitable organizations, as well as samples from donated drugs to public and charitable health institutions or newly registered, and rarely for samples of drugs that enter the private market [16]. Furthermore, analyses were carried out for locally manufactured drugs only and it could not process a large number of samples. The center also could not analyze cosmetic products [16].

2.2. Central Public Health Laboratory

- In 2013, the General Administration of Pharmacy founded a drug analysis unit on their laboratories. However, this unit has a very limited role in quality control analysis due to partial lack of appropriate instruments and staff. The number of drugs analyzed in this laboratory for MoH in 2013 and 2014 were 26 and 208 samples, respectively [30].

2.3. Center of Drug Analysis and Research

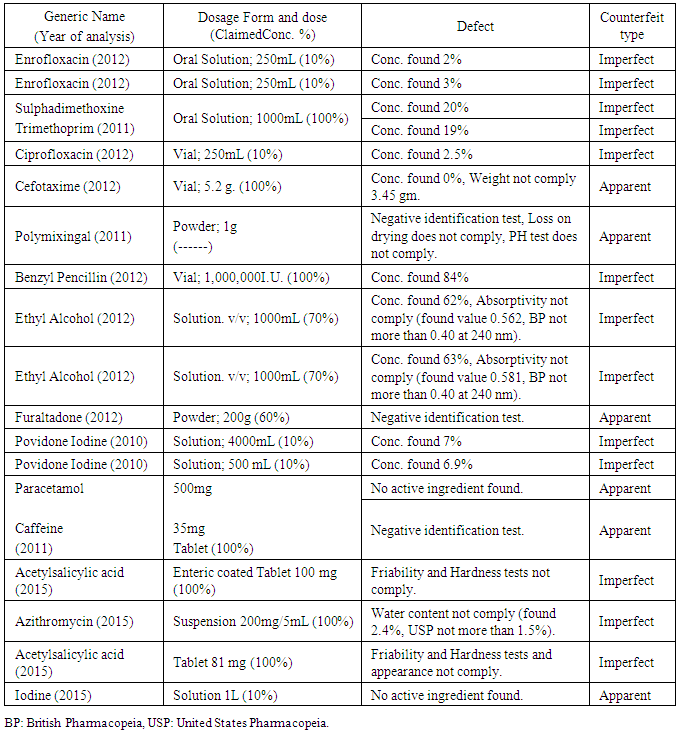

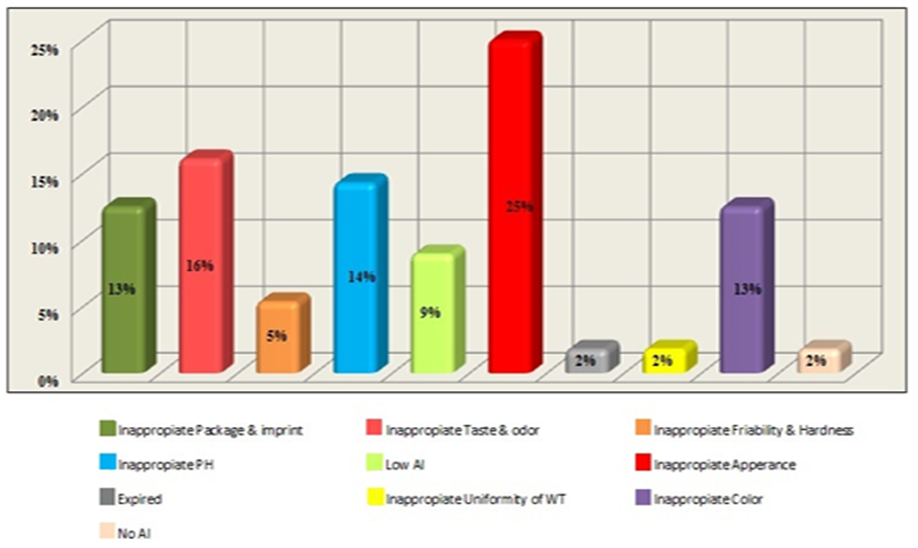

- The Center of Drug Analysis and Research of Al-Azhar University-Gaza was established in 1998 to serve the Palestinian community. It is the best qualified official center in the Gaza Strip. It offers drug quality certificate for routine control of locally manufactured, and externally imported drugs, as well as for the registration of new drug products. Furthermore, it offers quality control for veterinary products and raw materials. However, it has limited facilities in bioanalysis, analytical toxicology and testing of addictive substances [31]. The Center offers services for Al-Azhar University, and other universities in the Gaza Strip to help them carry out their scientific researches and offer consultation and service regarding instrumental analysis for academics and students. Furthermore, the center carries out different quality control tests for the MoH, the Ministry of Justice, United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (UNRWA), Pharmaceutical companies, and drug distributors. It is worth mentioning that the MoH in 2013 and 2014 analyzed 665 and 256 samples in this center, respectively [19, 30]. Table 3 and Figure 1 show some examples and causes of rejected drugs that were analyzed by the center, respectively.

|

| Figure 1. Causes of rejection for drugs analysed by the Center of Drug Analysis and Research of Al-Azhar University in Gaza in the time period between 1999-2013. AI: Active ingredient; WT: Weight |

3. Factors Encouraging Counterfeiting of Drugs in the Gaza Strip

- The loose control system in the Gaza economy has contributed to the circulation of fake and counterfeit drugs. There are general factors that contribute to counterfeiting of drugs in the Gaza Strip; Drugs are highly valued and strongly needed. The cost of fake products would be very low, because cheap substitutes can be used, no cost for quality assurance or meeting Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and can be produced in small cottage industries, buildings or in backyards. The factors facilitating the occurrence of counterfeit drugs vary from country to another. However, the most common factors are considered to be: lack of appropriate drug legislation prohibiting counterfeiting of drugs; inadequate, ineffective or weak drug regulatory control; unregulated importation, manufacture and distribution of drugs; weak enforcement and penal sanctions. Moreover, disregarding trademark rights may encourage large scale counterfeiting of drugs [32]. Demand of drugs exceeding supply, consumption of drugs in the Gaza Strip is very high. It is due to strong patient demand and irrational prescribing and over-prescribing by healthcare providers. Moreover, doctors tend to prescribe more expensive brand-name drugs. The pharmaceutical markets of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are not open to the international competition since Israel applies restrictions to protect its own market. If the Palestinian drug market was opened up to international competition, drug supply prices would decrease [16]. However, the cost of manufacture of counterfeit drugs is minimal and the profits to be made are significant. The presence of non-professionals in the pharmaceutical business is an additional contributing factor to the availability of counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip. These non-professionals are less capable of identifying fake drugs and are more out to make profit than seek the general wellbeing of the community. Probably, pharmaceuticals made for export are not regulated by many exporting countries to the same standard as those produced for domestic use. In addition, pharmaceuticals are sometimes exported through free trade zones where drug control is weak and where repackaging and re-labeling take place, as well as trade through several intermediaries. Greed, ignorance, corruption and conflict of interest are the driving forces behind poor drug regulation, which directly encourages drug counterfeiting [2, 16, 32].

4. Conclusions

- Drug counterfeiting remains one of the world's fastest growing industries, while the issue of counterfeit drugs has long been treated as an illicit case of circumvention of taxes; the view has often masked what is in fact a public health crisis. There is no published medical research assessing the prevalence, public health impact, or probable countermeasures for counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip. Highlighting the situation of counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip should influence policy to help reduce and eliminate the public health threat posed by these drugs.The counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip are pronounced in both public and private sectors. More than half of the total drugs supplied to MoH are donations and other main source of drugs in the Gaza Strip is smuggled drugs from Egypt. The precise percentage of counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip needs more research to determine. The role of MoH in routine check of drugs in central drug stores for public sector is getting better, but still need further development. Most importantly, the role of MoH in routine check of drugs in private sector is very poor and needs much more efforts and work.The result of counterfeit drugs diffusion in the Gaza Strip may lead to treatment failures, organ dysfunction or damage, worsening of chronic disease conditions and death of many patients. It is an important cause of mortality and morbidity and loss of public confidence in drugs and health structures. Even when patients are treated with genuine drugs, he/she might not respond due to resistance caused by previous intake of counterfeit drug. No single technique can eliminate the public health threat posed by counterfeit pharmaceuticals due to the complexity of the counterfeit drug problem.Education among the general public, distributors, wholesalers and retailers, as well as government agencies about the potential harm and damage to the public health and the severity of the issue will serve to reduce the prevalence of counterfeit drugs in the Gaza Strip.Ensuring the quality of drugs, in the public and private sectors, and combating counterfeiting of pharmaceutical products at national level is a shared responsibility involving, relevant government agencies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, health professionals, consumers and the general public. Governments have to create the appropriate environment for the participation of all concerned partners. Equally, the cooperation of the pharmaceutical industry, wholesalers and retailers to report to the drug regulatory authority cases of counterfeit drugs is necessary in combating this threat.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML