-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2016; 6(3): 66-72

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20160603.02

Prevalence and Socio-demographic Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity among Healthcare Workers in Kisumu East Sub-County, Kenya

Ondicho Z. M.1, Omondi D. O.2, Onyango A. C.3

1Department of Health Services, Koibatek Sub-County, Baringo County, Eldamaa Ravine, Kenya

2Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute and Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Maseno, Kenya

3Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Maseno, Kenya

Correspondence to: Ondicho Z. M., Department of Health Services, Koibatek Sub-County, Baringo County, Eldamaa Ravine, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Overweight and obesity are a serious public health problem globally. Healthcare workers in some countries have been reported to be having a high prevalence of overweight despite them being well informed of aetiology and risks of excessive body weight. However, the problem of overweight and obesity among Kenyan healthcare workers remain uninvestigated. Objective: The aim of this study was to assess prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among the Kenyan healthcare workers in Kisumu East SubCounty. Materials and Methods: This was a cross sectional study conducted between April and August 2014 involving 165 respondents sampled from 9 health facilities. Demographic, socio-economic and lifestyle Data was collected using questionnaires and anthropometric measurements were taken using electronic weighing scale and height measuring bar. Results: Mean age was 37.1 years and prevalence of overweight and obesity was 58.8%. Increasing age was significantly associated with overweight and obesity OR (95% CI) = 7.3(2.0-25.98) p=0.002 while sex, marital status and vigorous physical activity were associated with overweight and obesity but were not independent predictors. Conclusions: This study found high prevalence of overweight and obesity among healthcare workers, which was about three times the estimated national prevalence. Higher order age group emerged as the most conspicuous predictors of overweight and/or obesity.

Keywords: Overweight, Obesity, Healthcare workers, Non-Communicable diseases

Cite this paper: Ondicho Z. M., Omondi D. O., Onyango A. C., Prevalence and Socio-demographic Factors Associated with Overweight and Obesity among Healthcare Workers in Kisumu East Sub-County, Kenya, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 66-72. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20160603.02.

1. Introduction

- Overweight and obesity is one of the leading causes of preventable deaths globally [1]. According to the World Health Organization estimates in 2008, over 2.8 million deaths annually and 35.8 million (2.3%) of global Disability Adjusted Life Years are caused by overweight, making it the fifth leading risk for global deaths. In addition, 44% of the diabetes burden, 23% of the ischaemic heart disease burden and between 7% and 41% of certain cancer burdens are attributable to overweight and obesity [2]. In 2008, 1.4 billion adults were overweight. Of these, over 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese [3]. Population surveys done in various sub Saharan countries show that prevalence rate of overweight and obesity is increasing in the general population [4]. Furthermore, non-communicable diseases commonly associated with overweight and obesity such type II diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cancers and hypertension are gradually replacing infectious diseases as a major source of morbidity in African countries [5]. In Kenya, the proportion of overweight and obesity rose by 7.3% between the years 2003 and 2008 [6, 7]. The rise in overweight and obesity has majorly been attributed to sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, rapid urbanization, and improved socioeconomic status [8]. Other risk factors associated with overweight and obesity include increasing age, marital status, parity, alcohol intake and stress [9, 10].The risk of overweight and obesity is not uniformly spread across the population, some groups of persons have a higher risk relative to the general population. Such groups include healthcare workers. Even though healthcare workers are a group considered to be well informed about aetiology and risks of overweight and obesity, studies conducted in some countries including USA, Mexico, South Africa and Nigeria [11-14] have consistently found them to be disproportionately having a higher risk of overweight and obesity compared to the general population. To the best of our knowledge, similar studies have not been conducted among Kenyan healthcare workers. Lack of documented evidence in Kenya on the extent and determinants of overweight and obesity among Healthcare workers is worrying, as the problem may escalate unrecognized. The Kenya National Diabetes Strategy (2010-2015) acknowledges that little attention is given to prevention and control of overweight and obesity in the country due to lack of comprehensive research to inform design and implementation of appropriate overweight and obesity prevention programs [15]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine prevalence and risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among healthcare workers in Kisumu East Sub-County, Kenya between April and August 2014.

2. Materials and Methods

- This was a cross sectional study conducted in Kisumu East Sub-County, Kisumu County, Kenya. The Sub-county is located in Western Kenya besides Lake Victoria, it has an estimated population of half a million people and hosts Kisumu City, the third largest urban area in Kenya. Health facilities in the district comprise of 1 regional referral hospital, 1 Sub-County referral hospital, 7 health centers and 26 dispensaries and 14 private health facilities. The study population included 793 Health Care Workers in public health facilities and it was conducted between April and August 2014.Sample size was calculated using the formula n=z2pq/d2 where n = desired sample size if target population is > 10,000; z = standard normal deviate at the required confidence level (1.96); d = the marginal error allowed (0.05); p = prevalence of overweight and obesity in the study area (14%) [16], q = 1- p. Since target population was below 10, 000, an adjustment was made to the formula: nf = n/ (1+ n/N) where nf = the desired sample size when the population is less than 10,000; n = the desired sample size when the population is more than 10,000; N = the estimate of the actual target population. After making an allowance of 10% for non response, sample size was 165. All public health facilities in the Sub-County were included in the sampling frame. Thereafter, a sample size proportionate to population size in each facility was calculated. Sampling frame for participating health workers was obtained from each health facility. Healthcare workers were then stratified according to cadre and number of participants selected from each cadre was proportionate to its population size. Selection from each cadre was done by random sampling method with the aid of a random number generator.Demographic and lifestyle data was collected by use of a self administered questionnaire, anthropometric measurements were taken using electronic weighing scale for weight and height measuring bar for height. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using the formula; (kg)/height (m2). BMI was then classified according to World Health Organization guidelines [22]. Data collection tools were pretested in Ahero Sub-County Referral Hospital among 17 healthcare workers. The tools were adjusted appropriately according to feedback from the healthcare workers.

3. Results

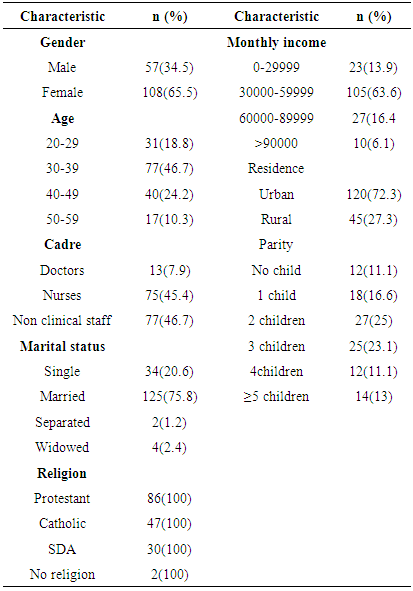

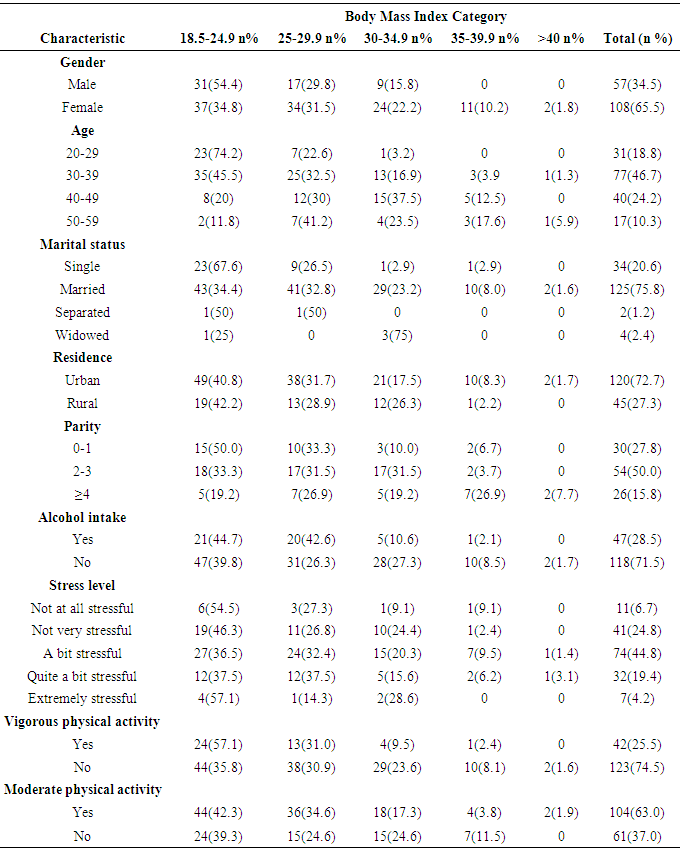

- Characteristics of the study participantsA total of 165 respondents were interviewed. Majority of those interviewed were females (65.5%). Mean age was 37.1 ± 8.7 years. About 47% of respondents were between the age of 30-39, 24% were between the age of 40-49 years while 18.8% were below 30 years. Non-clinical cadre staff comprised of 46.7% of participants while the rest were clinical cadre staff (Table 1).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

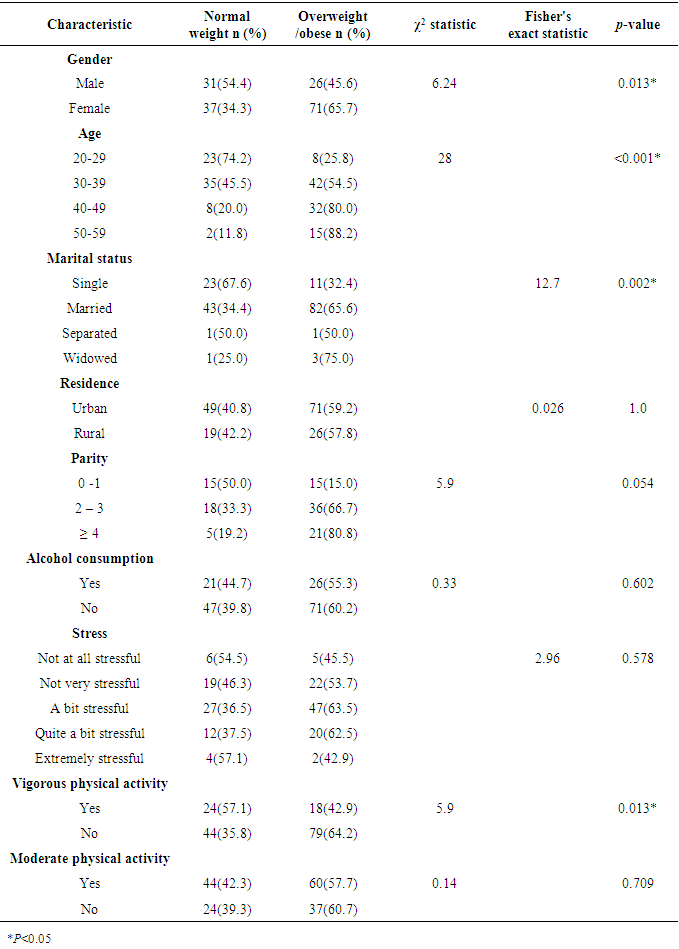

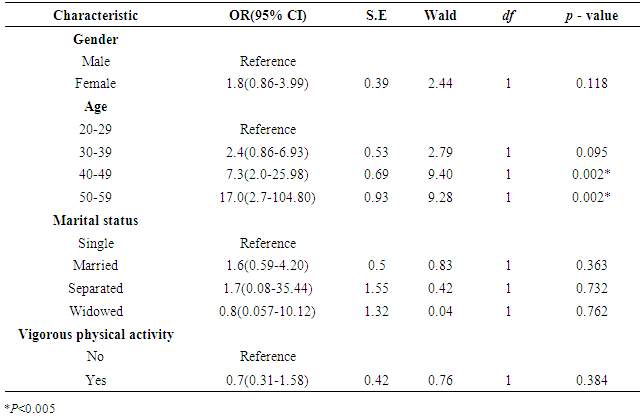

- This study found a high prevalence of overweight and obesity among Kenyan healthcare workers which was about 3 times the national average, estimated to be 20.5% by the WHO in 2008 [2]. This finding is consistent with similar studies conducted elsewhere that reported a disproportionately high prevalence of overweight and obesity prevalence among healthcare workers compared to the general population. In a cross sectional study conducted in Mexico among 76 participants, 26% and 52% of male and female healthcare workers respectively were reported to be obese [12]. Similarly, in a study conducted in South Africa among 200 healthcare workers in one tertiary health facility, prevalence of overweight and obesity was found to be 75% [13]. In Nigeria, 72% of healthcare workers in one tertiary health facility also were found to be either overweight or obese [14]. It should be noted that whereas participants in the mentioned studies were mostly sampled from one tertiary health facility, participants in this study were sampled from 9 health facilities within an administrative region. The high prevalence of overweight and obesity among the healthcare workers predisposes them to non communicable diseases including hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancers. Furthermore, unhealthy healthcare workers may not provide healthcare services optimally. Overweight/ obesity has been linked to reduced productivity and absence at the workplace [17, 18]. Health care workers ought to be role models in leading healthy lifestyle and maintaining normal body weight, this will not only contribute towards improvement in their own health status, but also enhance better health services delivery especially to overweight or obese patients. There is evidence that healthcare workers leading healthy lifestyle and those with normal Body Mass Index are more likely to counsel and motivate their patients to adopt healthy lifestyle and maintain normal body weight [19]. After controlling for confounding, age was the only independent predictor of overweight and obesity in the current study. Consistent with previous studies [20, 21], older participants had a significantly higher risk of overweight /obesity. Those between 40-49 years had a 6 times higher risk compared to respondents below 30 years. This could be attributed to a combination of factors such as reduction of physical activity and decrease in metabolic activity, both associated with increasing age [22]. Socio-demographic and lifestyle variables including gender, residence, parity, marital status and level of physical activity, alcohol intake and stress levels were not independently associated with overweight and obesity. Females had a significantly higher risk of overweight/ obesity compared to males. Various population surveys in developed and developing countries have reported similar findings [4, 23]. Females tend to gain the greatest amount of weight during the child bearing years, and some of them develop overweight/obesity through the retention of gestational weight gain [24]. In a study conducted in Iran, high prevalence of overweight and obesity in females was attributed to differences in level of physical activity [21]. Even though a significantly lower proportion of women (17.6%) engaged in vigorous physical activities compared to males (40.5%) p = 0.002, this did not account for differences in overweight/obesity prevalence. The similar prevalence rates found in both urban and rural areas is in contradiction with population based surveys done in developing countries that have consistently reported higher prevalence of overweight among residents of urban areas [7, 25]. The target population in this study was a fairly homogenous, it is therefore more likely that healthcare workers have similar lifestyle regardless of their area of residence. In this study, average monthly income, which was used as an indicator of socio-economic status was not associated with overweight and obesity (p = 0.403). The finding is contrary to similar studies done in developing countries, where higher socio economic status has been positively associated with overweight and obesity [20]. In our sample, monthly average income fell within a narrow range (median 47, 000 IQR 56000 – 30000); this could partially explain why monthly income did not have an effect on BMI status of the respondents. Parity has been significantly associated with overweight and obesity [26, 27]. Women within the child bearing age have elevated risk of overweight/obesity as a result of gaining and retaining of gestational weight [24]. However, such an observation was not made in this study owing to the relatively smaller sample studied. Studies investigating relationship between alcohol intake and BMI have yielded inconsistent results [28, 29]. Physiologically, oxidation of alcohol is prioritized over other macronutrients, some of the body’s energy needs is met while a greater proportion of energy from other foods is stored, this mechanism is thus associated with increased risk of abdominal obesity [30]. Finally, there was no association between stress levels and prevalence of overweight/obesity. However, a large percentage of respondents (68.5%) reported moderate to high levels of stress. We did not explore whether the reported stress was work related or otherwise. There are different ways in which persons respond to or cope with stress at work and at home. Some persons may deliberately indulge in behaviors predisposing them to weight gain and others may adopt behaviors associated with weight loss. So far, there is no conclusive evidence that stress is linked to Body Mass Index. A large scale study conducted in Canada involving 112,716 respondents reported an increased risk of obesity among participants with stress [31], whereas in some people, stress was associated with reduced Body Mass Index [32]. Mechanism through which stress leads to overweight is not well understood. Possible mechanism proposed is that, stress may activate a neural stress-response network, and induce eating in the absence of hunger. Another possible explanation is that stress induces secretion of glucocorticoids and insulin, resulting in an increase in intake of energy dense foods [32, 33].The high prevalence of overweight and obesity reported in this study has several implications for policy, action and research. There is need to promote and integrate healthy lifestyle in work places. Healthcare workers engaging in healthy lifestyle should be encouraged to continue, while those living unhealthy lifestyle should also be encouraged to start. Viable planned physical activities for health care workers include going to the gym or participating in a sporting activity. Unplanned exercises such as brisk walking should also be encouraged. Larger scale studies to investigate association of other determinants with overweight and obesity among Kenyan health care workers should be carried out since factors investigated in this study accounted for only 26% of the its variance. Particularly, the role of dietary patterns among healthcare workers should be investigated. Furthermore, overweight/obesity co- morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, cardio-vascular diseases and cancers among this group of workers ought also to be investigated. Human resource for health is scarce in most developing countries in Africa, non-communicable diseases that endanger retention of healthcare workers in service must receive adequate attention from policy makers and other relevant stakeholders.This study had limitations. Its design was cross-sectional, therefore causal relationship between risk factors and BMI status could not be established. Finally, this study was conducted among healthcare workers, therefore the findings can only be generalized to groups of persons with similar socio-economic and demographic characteristics and not the general population.In conclusion, this study found a high prevalence of overweight and obesity among Kenyan healthcare workers. Age was an independent significant predictor of overweight and/or obesity among the healthcare workers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank the healthcare workers in Kisumu East Sub-county who participated in this study. We also appreciate the leaderships of Kisumu County Department of Health Services, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital and Kisumu East Sub-county Department of Health Services for giving us permission to conduct our study within their areas of jurisdiction.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML