-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2016; 6(1): 7-15

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20160601.02

Hand Hygiene and Health Care Associated Infection: An Intervention Study

Slimah N. Abdraboh1, Waleed Milaat1, Iman K. Ramadan1, 2, Fatin M. Al-Sayes3, Khaled M Bahy4

1Community and Family Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, King AbdulAziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

3Hematology Department, Faculty of Medicine, King AbdulAziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Iman K. Ramadan, Community and Family Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, King AbdulAziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background:Healthcare-associated infection accounts for more deaths.There are millions spent annually as a direct cost, yet these infections are frequently preventable through hand hygiene. Although the hand hygiene is a relatively simple procedure, health care workers` compliance remains a major pitfall and a complex phenomenon that is not easily changed. To our knowledge, there are no published researches on hand hygiene knowledge and compliance changes after an intervention in King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital. Aim: The current research investigated hand hygiene knowledge and compliance among HCWs for the period of six months. Methods: A three-phase intervention study was conducted among all health care workers at King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital, using WHO structured self-administered questionnaire and Observation checklist, during the period from September 2014 to May 2015. Results:four hundred and eighty health care workers were invited and completed the study, with a response rate of 100%. Females constituted 78.3% of the population. More than half of HCWs (51.9%) were married. 85.2% of the HCWs were non- Saudi and two third with nursing background. Gender, department, baseline knowledge, and knowledge following three months of intervention were significantly associated with hand hygiene compliance. Conclusions: Hand hygiene improvement is affordable, and effective in healthcare setting, and a prolonged approach of education intervention and continuous observation results in improving hand hygiene knowledge and compliance.

Keywords: Hand Hygiene and Health Care

Cite this paper: Slimah N. Abdraboh, Waleed Milaat, Iman K. Ramadan, Fatin M. Al-Sayes, Khaled M Bahy, Hand Hygiene and Health Care Associated Infection: An Intervention Study, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 7-15. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20160601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Healthcare-associated infection (HCAI) is a serious burden disease for patient safety and should be promoted as a first priority for prevention and making healthcare settings safer. There are lots of impacts belonged to HCAI like prolonged hospital stay, long term disability, spread of antimicrobial resistant organisms, in addition to financial burdens, high risk of deaths, and extra costs for the health setting. [1] The Center of Disease Control CDC defined acute care HCAI as “a localized or systemic condition resulting from an adverse reaction to the presence of an infectious agents or its toxins”. “The infection should be neither present nor at the incubation period at the time of admission to the Intensive care setting.” [2]Hundreds of millions of patients around the world each year were affected by HCAI. [1] Therefore, HCAI remained a big concern that no organization or country can claim to have solved as yet. In developed countries, 5–15% of hospitalized patients were at risk to acquire infection particularly those admitted to intensive care units (ICUs). [1] Recent European study reported wide prevalence of hospital acquired infection (4.6% - 9.3%). [3] Also, in USA the estimated HCAI incidence rate was 4.5%. [1]On the other hand, in developing countries the prevalence study was carried out in Albania, Morocco, Tunisia and the United Republic of Tanzania, reported that HCAI was ranged between 19.1% and 14.8%. [4] Recently a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, Riyadh reported 8% HAI. [5]Fortunately, researchers reported that between 20% and 40% of HCAIs are preventable. [4] Hand hygiene at five moments is considered as the easiest way to anticipate the dissemination of infection. However, improving hand washing compliance and maintain this behavioral change is a significant challenge, because of the complexities of the health care environment and changing behavior. [6] Now it is recommended to practice hand hygiene as a basic for infection control for the sake of assuring patients. Though, increasing patient morbidity and mortality could be joined to the worldwide emergence and morbid dissemination of multidrug resistant pathogens. [7]“Hand hygiene is a general term that applies to routine hand washing, antiseptic hand wash, antiseptic hand rub, or surgical hand antisepsis.” [8] Although, it has long been recognized that effective hand hygiene was the crucial action to decrease the spread of infection in health care settings. Several studies, have reported that compliance to hand hygiene remains inefficient and needs corrective actions to be sustained. Therefore, the World Health Organization WHO, the CDC, have announced guidelines for hand hygiene among health care providers. [9]Although this simple procedure is very essential, it is not properly recognized by Healthcare workers HCWs, and a unsatisfactory compliance has been declared. [10]Hand hygiene link group defined nine controlled studies, reporting sound markdown in infections, same in highly infected places like intensive care units. Hand hygiene also, documented in reduction of transmission of Health-care-associated gram negative pathogen. [11]Therefore in 2005, World Health Organization floated the “First Global Patient Safety Challenge - Clean Care is Safer Care” aimed for global reduction of HAIs. Later, “SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands” initiative was declared to accentuate the role of hand washing in preventing health related infections. [12] For the sake of standardizing the optimum application of hand wash procedure, an approach was applied to distinguish, prepare, audit and address adherence to hand hygiene. [12] This standard was formulated as “My five moments for hand hygiene” which recognizes the basic points for health care providers and enforce when there is need for hand washing to breakdown the infection chain during taking care of patients. [11, 12]Several studies reported inadequate adherence to hand hygiene among healthcare providers (25% - 40%). [13-14] Despite that, systematic reviews of short-term non randomized studies reported that feedback might be the most successful intervention. [15, 16] Also, evidence from systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials, declared that feedback essentially improves healthcare workers’ compliance with other evidence-based guidelines. [17, 18]In 2011 an audit was carried out in 36 hospitals reported 74.7% as the average hand hygiene compliance score for all healthcare workers. Five months later they published the analyzed results from 42 hospitals and found that the average compliance had increased to 79.6%. [19]Education on proper methods of hand hygiene is the clue for dramatic reduction in the infection rate. A survey found an improved had hygiene knowledge for nurses in Singapore, after receiving comprehensive course of education. [20]Therefore, hospitals should arrange an action plan for departments that do not meet the target of hand hygiene compliance. These plans should include organized educational and training sessions and re-auditing until the target is achieved. Basically, there are three ways for investigating hand hygiene compliance; direct observation, product use measurement and survey conduction. [21]The gold standard among these methods is the direct auditing of the practice of hand hygiene among health care providers. Through, observation the used hand hygiene products careful cleaning, used equipment and procedure for dehydrating, used gloves, and providers performance in an opportunity can be documented. In addition, observation allows the observers to monitor the adherence to guidelines and to recommend prompt feedback whenever improvement is required. In contrast to these benefits, direct observation could be expensive, needs careful selection and training of the observers. [21]Unfortunately, compliance to hand hygiene guidelines is the lowest in critical care areas, however those patient are highly vulnerable to infection. [22-24]So, asserting healthcare workers` knowledge and awareness grant them efficiently ameliorated compliance with hand hygiene.

2. Subjects and Methods

- A three-phase quasi experimental study was conducted between September 2014 and May 2015. The study was carried out in King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital (KFAFH) in Jeddah. The hospital includes most major branches of medicine and surgery in addition to other departments like an intensive care unit, neonatology, and premature unit.The study population included all healthcare workers of King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital in critical care, emergency, medical and surgical departments. Four hundred eighty participants (100 physicians and 380 nurses) were recruited. 57 from Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (11 physicians and 46 nurses), 88 from Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (35physicians and 53 nurses), 100 from Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) (17 physicians and 83 nurses), 15 from Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) (5physicians and 10 nurses), 132 from Emergency Room (ER) (32 physicians and 100 nurses), 50 nurses from Medical ward who deal with critical care patients with competency of high dependent care, and also 38 Surgical ward nurses. All health care workers were identified by hospital ID.The study was carried out through three phases: ● Phase I (1 month): The preintervention phase, consisted of assessing HCWs' knowledge toward hand hygiene and baseline compliance to hand hygiene at the “World Health Organization’s (WHO) five moments” by link nurse in each department. [1]● Phase II (3 months): Intervention stage, comprised of the following four suphases: 1. Designing and implementing the intervention, based on the results of phase I. The intervention included educational group presentations which were adopted from WHO. [1] The intervention took the form of lectures and training workshop. These address the nessisity of hand washing, suggested plans to enhance hand washing, and different ways of observing hand hygiene. Continuos supply of alcohol gel was guranteed throughout the study. The reseracher conducted eight sessions with around 50 HCWs per session. 2. Immediate Posttest assessing knowledge level for the same selected group of HCWs. It was the same assessment questions of pre-test, and it was carried out immediately after the educational intervention.3. Immediate Observation of hand hygiene compliance immediately after the educational intervention through the link nurse who was trained for optimum filling the observation checklist.4. Feedback on baseline health care associated infection rate.● Phase III (1 month): postintervention follow up phase, three months later after the intervention stage, comprised of the following three substages: 1. Three months Post-test to assess knowledge level three months after the educational intervention among the same group of selected HCWs. 2. Observation of hand hygiene compliance three months after the intervention through the link nurse.3. Feedback on health care associated infection rates three months after the intervention.Study Instruments:∎ Part I Structured self-administered questionnaire consistingof the following two sections:A. Basic Characterstics of the study population:● Demographic data: Age, sex, nationality, marital status, background, and years of experience. ● Department, work shift, number of patients served by HCWs, attended training on hand hygiene, and sources of their hand hygiene knowledge.B. Questions assessing the knowledge of hand hygiene adopted from valid reliable, WHO’s hand hygiene questionnaire for health care workers [1]. This questionnaire consists of seven questions; six multiple choice questions and one “true” or “false” question. The seven questions cover; Situations where hand hygiene should be performed The efficient way to decrease number of bacteria on the blood soiled hands, the most frequent method of transmission of resistant baceria, infections which could be dissminated between health care providers and patients particularly when hand hygiene precautions were not taken into consideration, effect of alcohol-based hand hygiene products on Clostridium difficile, regular daily pathogens that survive in the patients` environment, and facts about alcohol-based hand hygiene products. Correct answers were coded as one and incorrect answers were coded as zero. The process of distributing the self-administered questionnaire among the HCWs was performed in a private room in the selected units, after informing HCWs about the study objectives and obtaining their written informed consent and ensuring the confidentiality of dealing with data. ∎ Part II Hand Hygiene Observation Checklist. This checklist was used during direct observation of healthcare workers providing patient care in the relevant department by well trained link nurse from Infection Prevention and Control Department (IPCD). Each link nurse was allocated to department and had a uniform educational and training session on how to observe hand hygiene compliance, and fill in the form in the relevant department. Each time an observed health-care worker entered the patient zone from the health-care area the link nurse observe the “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene”: before contact with patient, or an aseptic procedure, after exposure to any body fluid, after any contact with patient and his environment. The assigned link nurse noted the observed or missed hand hygiene actions associated with these indications and documented the data by scene and professional group, she also collected the information during twenty minute sitting (more or less than 10 min.) and did not observe more than three health‐care workers simultaneously”.In order to minimize the potential bias attributed to variability in training, skills and experience of the link nurse, the researcher used the following equation to calculate the inter-rater reliability: Number of Agreements / (Number of Agreements + Number of Disagreements). The link nurse was considered to be consistent if she achieves an inter rater reliability score ≥ 0.7. [6]Compliance to hand hygiene through; using alcohol based hand rubbing and hand washing practices were recorded against the opportunities. A pilot study was conducted on 10 HCWs (5 physicians and 5 nurses) to clarify the applicability and suitability of the questionnaire, identify difficulties that might be faced during administration, and estimate the time needed for filling the questionnaire. Overall, the questionnaire was suitable and took 3 to 5 minutes on average and no items required modification.

3. Ethical Considerations

- The Ethical Committee at King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, and King Abdulaziz University, approved the research. The permission of the head of each recruited departemnt was obtained. Consent Form started with simple explanation of the study aim. It confirmed the confidentiality of data. It included the researcher phone number and all possible communicating methods. It guaranteed the safe withdrawal from the study without affection of the work. It also, insured that all participants be informed about the study results. Statistical Analysis:Data Coding was carried out manually and then fed to the computer using STATA, version 13. Personal data that can identify the personality of the participant (ID) were not entered to data file to guarantee full confidentiality. The researcher hired a data entry and then checked randomly 10% of entries for potential errors. The range, minimum and maximum values, distributions and cross tabulations were checked to ensure that all questions had valid codes and values. The continuous variable age was summarized as mean and standard deviation. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical demographic and background data (gender, nationality, marital status, background, years of experience, department, shift, number of served patients per day, training attendance and source of hand hygiene knowledge). The outcome hand hygiene knoweldge was reported as a score ranged between zero and seven, while the compliance outcome was reported as compliant “1” and noncompliant “0”. The relationship between HCWs characteristics and knoweldge score was tested using a t test; while for marital status and sources of hand hygien knoweldge the resercher used one way ANOVA.The relationship between HCWs` characteristics and hand hygiene compliance was tested using a chi square test for all categorical variables The relationship between three phases of knoweldge and HCWs basic characteristics was tested using paired t- test. The relationship between three phases of hand hygiene compliance and HCWs characteristics was tested using a McNemar test. All p values were be two sided and the significance level was be set at α=0.05. Conditional Logistic Regression model was plotted to examine the predictor variables for changes of HCWs` hand hygiene compliance. The main model consisted of following predictor variables: gender (male was the reference), departemnt (ER was the reference), baseline knoweldge andknoweledge three months after intervention.Incidence rate ratio was calculated for the health acquired infection rate at baseline and three months after the intervention “HCAIs/person-days”.

4. Results

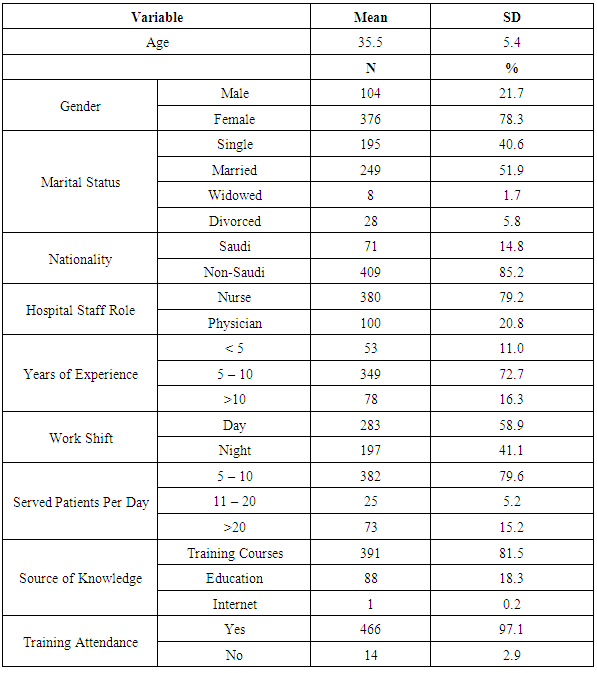

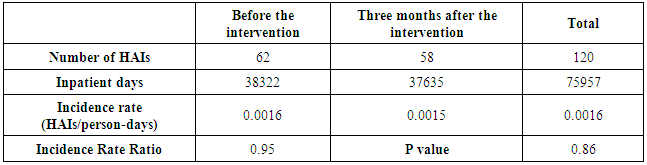

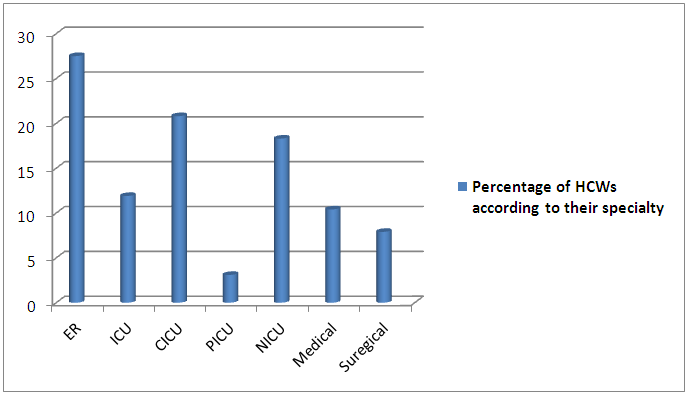

- All 480 health care workers were invited and completed the study, with a response rate of 100%. There were 132 (27.5%) HCWs from the ER, 100 (20.8)% from the CICU, 88 (18.3%) from the NICU, 57 (11.9%) from the ICU, 50 (10.4%) from the medical department, 38 (7.9%) from the surgical department and only 15 (3.1%) from the PICU (Figure 1). The average age was 35.5±5.4 years with a median of 36 years and a range from 24 to 57 years. Females constituted 78.3% of the sample population. More than half of HCWs (51.9%) were married. Almost all of the HCWs were non- Saudi (85.2%) and with nursing background (79.2%). In terms of their years of experience, 72.2% were had on average 5-10 years, 16.3% had more than 10 years and only 11.0% had less than 5 years of experience. More than half of HCWs (58.9%) were assigned for day shift work. The majority serve from 5 to 10 patients per day compared to 20.2 % who served more than 10 patients per day. Almost all HCWs (97.1%) were previously attended training courses regarding hand hygiene practice and nearly the same percentage (81.5%) reported that their knowledge towards hand hygiene was gained through training courses. (Table 1)

| Figure 1. Distribution of health care workers according to specialty |

|

|

|

|

|

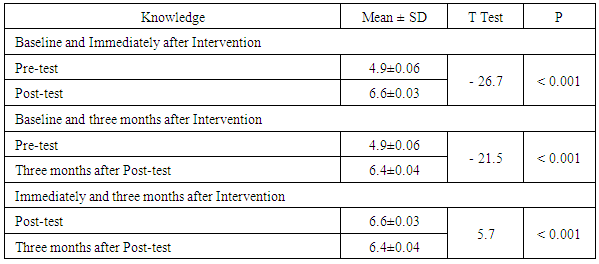

5. Discussion

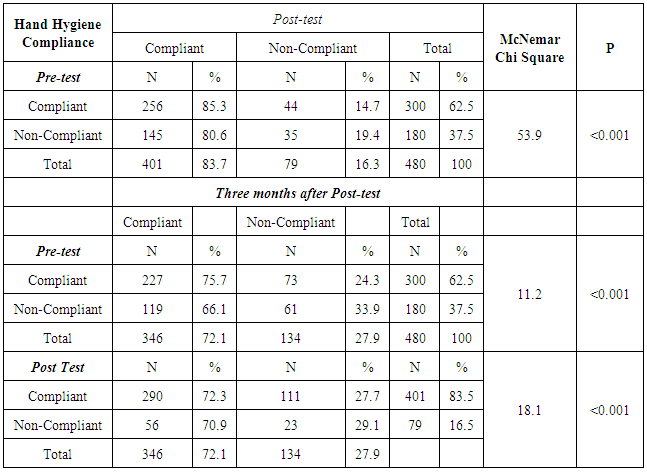

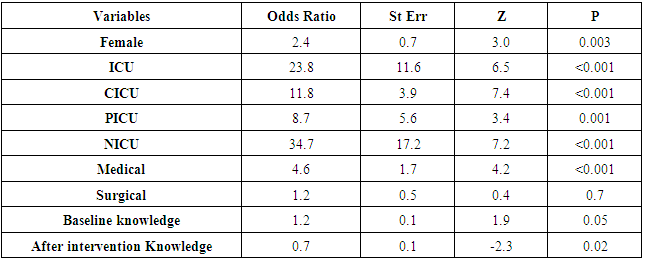

- Despite proper hand hygiene compliance remains as a backbone for HAIs prevention, lots of studies in a developed and a developing countries continued to identify improper compliance. The same dilemma is being faced at King Fahad Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah (KFAFH) which is a tertiary hospital which serves as a referral center for all military population in the western region in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. An indefinite number of variables are related to insufficient compliance with variable methods in auditing and declaring depending on the available resources and different settings. Defining the missed opportunities during providing care to patient is absolutely necessary so can be figured out for implementing a new policy. It was deep-seated that the WHO campaign is efficient at enhancing HCWs hand hygiene compliance and determined definite interventions that effectively advance the hand hygiene practices in hospitals, when appropriately implemented appropriately. [25]Although the hand hygiene is a relatively simple procedure which only takes 60 seconds for hand wash and 20 to 30 seconds for hand rubs as recommended by the WHO, HCWs` compliance remains a major pitfall and a complex phenomenon that is not easily explained or changed. This is obviously due to each time a healthcare worker stops to wash, gel, or foam their hands, it takes only short time, though the situations could add up to a reasonable period of time over the day.The researcher was aroused by the various available studies, however contrary to last documents from Saudi Arabia, it is the novel research specifying both hand hygiene knowledge and compliance in Jeddah using the “WHO hand hygiene knowledge and observation”. [26]The current study showed a dramatic improvement in hand hygiene knowledge among health care workers immediately and three months following a hospital-wide educational intervention. This finding could be attributed to an effective educational intervention and setting hand hygiene as a priority for patient safety among health care workers. These findings are supported by what was reported by Tan and Olivo, 2015 that knowledge of health related infections and hand hygiene among health care providers is pretty great. [27]Improved knowledge was maintained and audited allover many hospital areas. [21] This is consistent with the present study results which demonstrated the best knowledge at baseline and after three months of intervention in the NICU followed by surgical, ICU, CICU, PICU and ER. When assessing the knowledge three months after intervention, we found better knowledge among physicians compared to nurses. This is possibly because of a higher level of education or different cultural aspects. This is supported with what previous study reported that a less compliant nurses reporting inefficient attitude towards time. [35] Surprisingly optimal knowledge was reported among physicians who served more than twenty patients per shift this could be explained by their willing to learn more about hand hygiene to protect themselves and their patients.This is inline with what a previous four phases study reported; prior to the intervention the most adherence was in the NICU which sustained across the study phases then dropped in Phase IV, and the least was in the kidney center. However, great maintained advancement in adherence was noticed in the ICU all over the study. [28]Interestingly, regarding HCWs` hand hygiene compliance, the present study demonstrated higher baseline compliance (62.5%) compared to what was reported by other study (21%) (Elsevier 2012) they explained this low rate by the lack of sinks and work overload. The higher base line compliance in the current study could be attributed to several factors; there was MERS-CoV outbreak before starting the study in this case Saudi Arabia media was directed to the significance of hand hygiene and distribution of educational material to emphasize this issue. Also we could not ignore the effect of endorsing Islamic habits by Muslin healthcare providers in their daily practice. Hand hygiene is not only an activity proposed for body cleaning but it is made for traditional aspects and because it conveys a cardinal obligation in everyday life situations as proposed by many cultures and religions. Prophet Muhammad often praised Muslims to wash hands thoroughly and after apparently definite act: before and after eating; after using the bathroom; and after touching a soiled object. So, as Islam begins, a firm observation of hand hygiene with clear running water has been proposed to be Muslims. [29]Despite this good baseline compliance, we observed a striking improvement after educational intervention and those who was non compliant turned to be compliant. Unfortunately, this compliance is reduced after three month from educational intervention (83.5% to 72%). This could be explained by work overload, visitors’ inflow, the availability of facilities. This could be associated with the fact that time the hospital was flooded with patients and thus outnumbering the facilities available in the hospital. This is in agreement with a study which reported 67% total hospital hand hygiene compliance rate, and this rate was raised to 81% in the post-intervention phase, but decreased again after six months to be 59%. [21]Females tended to care about their hand hygiene compared to males and this is documented by the current results which found better female baseline compliance. This is due to that majority of females are married and they are taking care of their family and so they are keen to protect themselves against infections.All HCWs who worked in critical care area are practicing hand hygiene better than others; on the other hand ER had the lowest baseline compliance this could possibly due to the large number of patients served in ER so the HCWs did not have time to wash their hands properly between patients. By evaluating the effect of the educational intervention on the improvement of HCWs` compliance the current study observed a significant improvement either immediately or after three months following the intervention and it was obvious in both NICU and PICU and this could be related to effective ongoing auditing, monitoring and leadership especially in those two units. This is confirmed with what Nteli et al. (2012) [30] demonstrated that educational session was among the most essential activities to develop HCWs` hand hygiene compliance. Contradicting to the present study results, De Wandel et al. (2010) claimed that enhancing hand hygiene compliance was not achieved either with concurring a high level of knowledge or with social influence. Self-efficacy is an important agent for hand hygiene compliance. Also, this is This is confronted with what a 2010 Cochrane systematic review reported inadequate proves that interventions could enhance hand hygiene in the hospital. One study reported a significant hand hygiene improvement four months following the intervention, and other study did not find any effect after three months of the intervention. [31]There are many published researches assessing the long term impact of proper hand hygiene compliance on reducing the incidence of healthcare associated infection. Pessoa-Silva et al. (2007) [32] and Min (2013) [33] recorded that regular auditing is sufficient to improve adherence and is autonomously linked with reducing the infection rate. Despite, that many researches showed a transient association between advanced hand-hygiene compliance and declined infections, no one reached a continuous amelioration for long period “> 6 months”. Indeed, we have shown that there is no link between improving hand hygiene compliance and reduction in the HAI rate. As this needs a long term not only three months program. By analyzing the relationship between knowledge and hand hygiene compliance, the present study showed a significant relation and this is a very good sign that knowledge is aligned with practice. By constructing a model for the potential factors which could possibly predict good HCWs` hand hygiene compliance following the intervention, the study showed that, being married, divorced, working in the ICU or NICU, during day shift, and with good knowledge meant that you are a good hand hygiene compliant.All in all, the present study showed a significant relationship between knowledge and hand-hygiene compliance, providing a very good indication that knowledge is indeed aligned with practice. Lack of a true control group from health care workers might be considered as a limitation, finding a truly comparable group was difficult because it is part of the program to allow each health care worker to gain this type of knowledge. In addition, there was potential confounding by secular trends as there were other changes that occurred between the pre- and post-intervention periods aside from the intervention itself.Future studies are recommended to explore both hand hygiene compliance and its long term effectiveness on reducing healthcare associated infection rate. Patient and Staff engagement and positive role modeling are expressive interventions to advocate and enhance hand hygiene compliance. All service providers and receiver should consider hand hygiene a basic superiority.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML