-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2015; 5(6): 273-278

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20150506.01

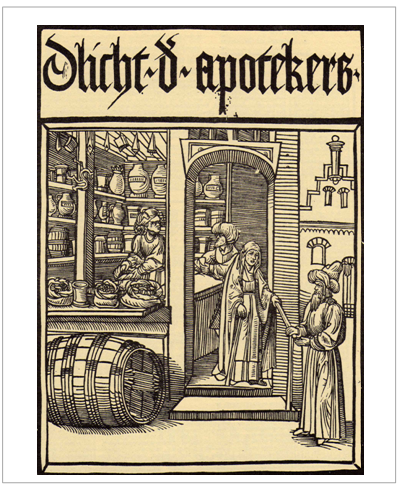

Apothecary Clothing in Time of the Burgundian State

Nanno Bolt

Society of the History of Pharmacy in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, Thury, France

Correspondence to: Nanno Bolt, Society of the History of Pharmacy in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, Thury, France.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The State of Burgundy from Charles the Bold included in 1477 the Low Countries (comprising large parts of present-day Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and northern France) as well the duchy of Burgundy and the counties of Nevers and Burgundy. The purpose of this study is to reveal more details on apothecary clothing during the 15th and 16th century within the territory of the Burgundian State. Identification of apothecaries has been accomplished based on a wide spectrum of (incidentally) sources. Details on the clothing of apothecaries were obtained by studying contractual documents, inventories, Burgundian Court accounts, pictures and sculptures. It is concluded that within the territory of the State of Burgundy the apothecaries in the 15th and 16th century were dressed similar to anybody else from the same social class. Based on the findings of this study some additional fine-tuning can be introduced: the court-apothecary wore court-clothing with the colours of the Burgundian, Bavarian or Guelders Court, the town-apothecary – being a municipal servant – wore the municipal clothing, an apothecary transformed into a medical-master wore a long black toga with damask lining and the ordinary apothecary followed the fashion of his social and financial standing: the higher middle class.

Keywords: Master-Apothecary, Burgundian State, Apothecary clothing, Court-Apothecaries

Cite this paper: Nanno Bolt, Apothecary Clothing in Time of the Burgundian State, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 6, 2015, pp. 273-278. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150506.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Most studies on the history of mediaeval apothecaries are country-based. But the State of Burgundy included in 1477 large parts of the actual Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France. [1] A (further) administrative cohesion for this territory was developed during the reign of Philip the Good with the convocation of the States-General in 1464 in Bruges. After the Act of Abjuration in 1584, the last link between the Netherlands and Burgundy expired. The purpose of this study is to reveal more details on apothecary clothing during the 15th and 16th century within the territory of the Burgundy State.

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of Apothecaries within the Territory of the Burgundian State

- In the 15th and 16th century a systematic administration of guild members did hardly exist: the first guild administrations origin in general from the end of the 16th century. Identification of apothecaries from the 15th and 16th century has been accomplished based on a wide spectrum of (incidentally) sources, such as appointment agreements between a town-apothecary and the town Magistrate, mentions in deeds of house sale, in heritage arrangements, in account registers from abbeys, churches, noble courts and town councils.A data base has been compiled by the author, based on publications in the Netherlands, Belgium and France, containing about 1000 apothecaries in 77 towns in the State of Burgundy during the 15th and 16th century. See for examples [2] and for the data base of the Low Countries. [3]

2.2. Obtaining Details on the Clothing of Apothecaries

- Details on the clothing of apothecaries were obtained by studying contractual documents, inventories, Burgundian Court accounts, pictures and sculptures.

3. Results

3.1. Clothing in the late Middle Ages

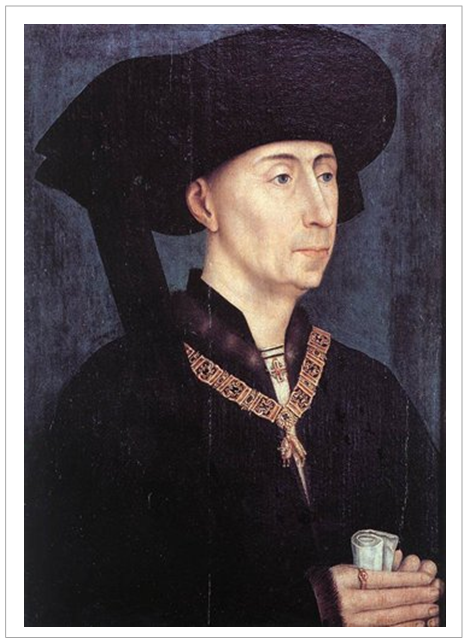

- Mediaeval clothing reflected the social standing of the person wearing them. During the 15th century the middle class (male) citizens wore clothing made up of a tunic, a super tunic or loose garment, long stockings tied to the girdle, a cape as outdoor wear and a wide variety of hat shapes: from small conic hats to turban like shapes and chaperons. Clothing was made of wool, linen, silk, fur and brocade. The more luxury robes of the higher and noble classes show often embroidery around the edges with silver or gold jewelled decorations. Dress fashion was primarily developed at the noble courts and followed by the higher class citizens later on. In the 15the century the Burgundian duchy was a trend setting court where the most luxurious robes, the most imaginative head-gear and the longest trains were found. [4]

| Figure 1. Examples of the wide variety of hat shapes. Polychrome sculpture, Amiens cathedral 1495 |

| Figure 2. Philip the Good with an unusually large bourrelet (Rogier Van der Weyden, 1450) |

3.2. Apothecary Clothing in the 15th and 16th Century

3.2.1. Apothecaries at the Courts of The Hague, Arnhem and Dijon

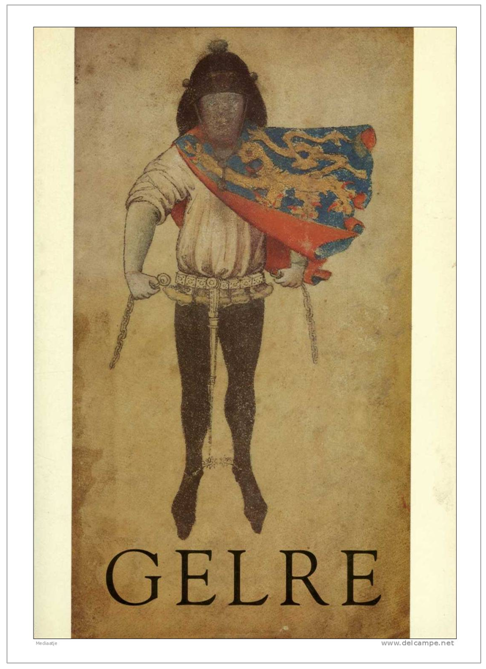

- In 1397 the apothecary Collaert van Ballustre got permission from the Duke Albert of Bavaria – who was (deputy) count of Holland and Zeeland as well – to establish a pharmacy in The Hague. Having a small client potential – the village of ‘’Der Haghe’’ counted 1300 inhabitants – the Duke granted additional privileges such as exemption from paying rent and heating costs (blocks of peat free of charge) and free court clothing. (“ende een roc vanden pleynen van onsen garsoenen clederen als men die geeft”). [6] As a court apothecary, Collaert wore highly probable a garment with the colours of Bavaria. Those Bavarian colours can be found in the Grand Armorial of the Golden Fleece, established in 1430 in Bruges by Philip the Good.Figure 5 shows the coat-of-arms in 1396 of the Duke of Bavaria in the Bavarian Armorial, comprising over 1000 coats-of-arms and which can be seen as a who is who in the Middle Ages. It was compiled by the herald Claes Heyenzoon, who administrated the coats-of-arms and announced the knights during tournaments. Recording heraldry was important at that time, among other things for indicating to which lord one belongs, not insignificant at the battle-field.In Arnhem we come across a court apothecary at that time as well: from 1395 apothecary Henricus Brant is purveyor to the Guelders Court. After the succession of Duke William by Duke Reynold IV in 1402, Brant was included into the Court of Guelders and received court clothing as well. [8] He should have worn the colours of the Duke of Guelders similar to the colours in the portrait of the herald Gelre from 1395 (Fig. 6). This herald Gelre is the same Claes Heyenzoon who we found a year later into service of the Bavarian Court.

| Figure 4. The colours of the Duke of Bavaria as painted in gouache in the Grand Armorial of the Golden Fleece (1430) [7] |

| Figure 5. The coat-of-arms of the Duke of Bavaria as represented in the Bavarian Armorial (1396) [7] |

| Figure 6. Portrait of the herald Gelre in the Gelre Armorial (1395) [7] |

|

3.2.2. The Ordinary Apothecary at the Turn of the 15th and 16th Century

- The frontispiece (Figure 1) of the Netherlands translation of the Lumen Apothecariorum, edited in 1515, was especially designed for this edition, with the typical Dutch house at the right of the picture. It gives an impression of the pharmacy and the clothing at that time. We see the apothecary and two of his male clients more or less similar dressed with their turban shaped head-dresses and in (early) mediaeval costume.From the same period (1508-1522) origins a wooden sculpture of an apothecary on the armrest of the choir-stalls at Amiens cathedral. The choir-stalls with their 110 wooden sculptures represent on micro-level the society of Amiens in that period with sculptures of the clergy, citizens and craftsmen. The apothecary is wearing a flat head-dress lifted up in the back, a doublet with puff-sleeves and puff-cuffs, a skirt with four rounded off flaps – perhaps a working-apron – and long stockings. Sossa [12] and Lemé-Hébuterne [13] conclude both that this apothecary is not wearing specific (guild-) clothing but follows the fashion of his social and financial standing: the higher middle class.Between 1502 and 1528 – overlapping the period of sculpturing the armrests of the choir-stalls – only 3 or 4 apothecaries were established in Amiens. From one of them, apothecary Jehan de Louvegny, the inventory is drawn up after his death in 1520. [14] He was among others owner of an old satin doublet, puff-cuffs, a bonnet and two shirts, like the clothing of the apothecary on the armrest.

| Figure 7. Frontispiece of “d’licht d’apothekers (1515) |

| Figure 8. Wooden sculpture of an apothecary on the armrest of the choir-stalls at Amiens cathedral (1508-1522) |

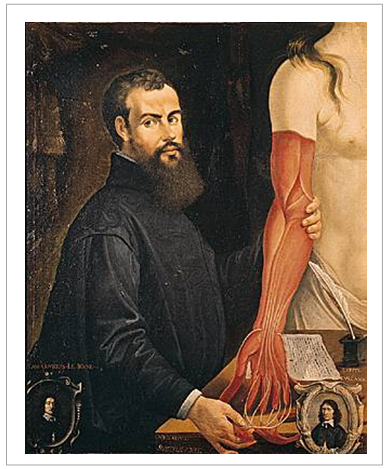

3.2.3. The Ordinary Apothecary: Special Cases

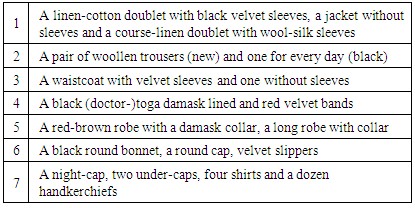

- Medical master and master apothecary Claes Corneliszn.An inventory for the orphan’s court at April 4, 1587 reveals that the Leyden apothecary Claes Corneliszn wore as an official robe a long black toga with damask lining like a medical doctor. In fact Claes Corneliszn obtained in 1554 the degree of medical master (“meester-medicyn”) and was allowed to wear a doctor’s robe. In a decree from 1553 the Magistrate of Leyden proclaimed that only academic educated doctors were allowed to exercise their profession and they had to show their sealed bull. However those who had exercised this profession before, without an academic education, were permitted to continue on condition that they had been examined by two “doctores medicinae”. It was March 19, 1554 that Claes Corneliszn visited in Amsterdam the doctors Dominicus Nardus and Gherit Hendricksz and that they concluded that Claes Corneliszn disposed of enough expertise to continue his medical activities and was allowed to operate human bodies as well (“Claes Corneliszn sal moghen opereren artem Medica in menschen lichaem als anderen practizynen”). [15]Town-apothecary Adam Dibbitz.In the Register of Counsel-resolutions of the city of Arnhem a resolution from June 20, 1587 is found – under the headline “Apothequar” – stating that the town apothecary, being a municipal servant, should wear the municipal clothing. [16] The only known apothecary in 1587 in Arnhem is Adam Dibbitz [3], so it is likely that Adam Dibbitz wore the municipal clothing of the city of Arnhem.

| Figure 9. Example of black doctor-toga, damask lined as worn by Andreas Vesalius (anatomist 1514-1564) |

|

4. Discussion

- In a study from 1930 [17] the question “how was an apothecary dressed in the 15th and 16th century” was addressed with the statement: similar to the dress of anybody else from the same social class. This study underlines this thesis for the ordinary apothecary as illustrated with the wooden sculpture on the armrest of the choir-stalls at Amiens cathedral, the inventory of Jehan de Louvigny and the frontispiece of the Netherlands translation of the Lumen Apothecariorum.On the other hand in Montpellier – forerunner in medical and pharmaceutical developments and regulations in the (late) Middle Ages – the apothecary robe was formally known. [18] In 1575 a paragraph was added to the articles of the association of pharmacists, stating that no master-apothecary was allowed to examine a candidate without wearing a long robe on penalty of 5 sols for each infringement. The first fine was already imposed on May 9, 1575 to two master-apothecaries without long robes. It is supposed that the robe was black coloured and similar to the actual toga of a lawyer. The robe was only worn at formal ceremonies. As a token of knowledge and erudition the graduate received a round head-dress, smaller than the square head-dress of the medical doctor. From that time origins in and around Montpellier the expression “to receive the master-bonnet”.

5. Conclusions

- Within the territory of the State of Burgundy the apothecaries in the 15th and 16the century were dressed similar to anybody-else from the same social class. Based on the findings of this study some additional fine-tuning to this statement can be introduced:− the court-apothecary wore court-clothing with the colours of the Burgundian, Bavarian or Guelders Court− a town-apothecary, being a municipal servant, wore the municipal clothing− an apothecary transformed into a medical-master wore a long black toga with damask lining− the ordinary apothecary followed the fashion of his social and financial standing: the higher middle class

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML