Efegbere HA1, 2, Afiadigwe E3, Anyabolu AE4, Enemuo HE4, Efegbere EK2, Ebenebe EU1, Ezejiofor OI4, Onyeyili AN5, Sani-Gwarzo N2, 6, Omoniyi A2, 6, Ilika LI1, Igwegbe AO7, Oyeka CE8

1Department of Community Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

2Department of Research and Training, Global Community Health Foundation, Nnewi, Nigeria

3Department of Surgery, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

4Department of Internal Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

5Department of Nursing Services, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

6Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria

7Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

8Department of Statistics, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Campus, Awka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Efegbere HA, Department of Community Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Background:No reliable method exist to predict which patient will complete Tuberculosis (TB) treatment, however, failure to complete treatment has been associated with several factors including alcohol abuse, drug abuse, homelessness, HIV/AIDS infection , non-compliance to anti-tuberculosis treatment due to a poor correlation between patient and programme needs and priorities, relatively long period of treatment, the need for multiple drugs and socio-economic factors.MaterialsandMethods:A retrospective cohort study design used to analyze secondary data set (2007-2010) of patients accessing determinants of Tuberculosis – Directly Observed Therapy Short Course (TB-DOTS) outcomes in two comparable public facilities (Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, NAUTH and Department of Health Services Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Unit Nnewi North Local Government Area [L.G.A.] Secretariat, DHSTLCU) in Nnewi North L.G.A., Anambra State. Multivariate Logistic Regression was used to analyze for determinants.Results:Patients mean age 35.0±3.3. There were 69% (1000 patients) and 57% (250 patients) males at NAUTH and DHSTLCU respectively. In 2007-2010 the determinants of treatment outcome at NAUTH were year, category of treatment and sex of patient for defaulter treatment rate outcome; year and category of treatment for transferred-out rate outcome; category of treatment for failure rate outcome; year and HIV status of patients for death rate outcome; year and category of treatment for success rate outcome. In DHSTBLU, the determinants were year and category of treatment for cured rate outcome; only year for transferred-out rate outcome; only age for treatment failure rate outcome. Conclusions: Determinants of treatment outcomes at NAUTH were year, category of treatment, sex and HIV status of patient while at DHSTLCU, the determinants were year, category of treatment and age. Therefore, its recommended, further research to focus on the determinants for disaggregated respective years, identify centre-specific factors associated with poor treatment outcome, emphasise the place of treatment success rate and analyse primary data set for Tuberculosis epidemiological profiling and comprehensiveness.

Keywords:

Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Determinants, Treatments Outcomes, Public Mix

Cite this paper: Efegbere HA, Afiadigwe E, Anyabolu AE, Enemuo HE, Efegbere EK, Ebenebe EU, Ezejiofor OI, Onyeyili AN, Sani-Gwarzo N, Omoniyi A, Ilika LI, Igwegbe AO, Oyeka CE, Determinants of Treatment Outcomes of Public Mix Tuberculosis Control Programme in South-Eastern Nigeria, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 5, 2015, pp. 235-245. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150505.09.

1. Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from any single infectious disease in the world. [1] Moreover, Nigeria has the highest estimated number of new TB cases among the African countries (200,000 annually). [2] Completion of treatment of active cases is therefore the most important priority of tuberculosis control programmes. [3] WHO reports that infection with HIV is the main reason for failure to meet tuberculosis control targets in regions with high HIV prevalence. [4] More over, other risks factors that have contributed toward the persistent increase in the burden of tuberculosis in developing countries are political strife and war, lack of political commitment from government, lack of resources to effectively manage and deliver health care, poverty, alcohol and drug abuse, the long duration of treatment, the need for multiple drugs, socio-economic factors including personalities of patients and poor monthly compliance of patients to bacteriological surveillance via sputum smear microscopy. [5-9] Studies in Nigeria report males had a higher risk of poor treatment outcome than females, patients with a poor knowledge of tuberculosis had a higher risk of having a poor treatment outcome compared to those with a good knowledge of tuberculosis, older age, rural residence , smear negative PTB, retreatment. [10-13] Determinants for successful treatment might require addressing multiple factors beyond simple supervision of drug intake to HIV status of patients, inadequate health service infrastructure, insufficient decentralization of both diagnostic and treatment services and inadequate human, material and financial resources. [11-19] The treatment of TB in Nnewi is organized to follow the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme (NTBLCP) guidelines. [20] Although, completion of treatment is monitored primarily by the Department of Health Services Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Unit (DHSTLCU), Nnewi North LGA information on treatment outcome of public public mix form of collaboration is rarely reported.

2. Materials and Methods

i. Study Area/ Sites:Nnewi has an area dimension of 72 km2 and an approximate population of 155,443 (77,517 males and 77,926 females) with average population density of 2159 people per km2. [19] Igbo language is the vernacular though English is widely spoken. There are about 64 registered hospitals at Nnewi, 2 missionary hospitals, 1 tertiary (Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital) and 24 primary health centres. [20]ii. Sampling Technique:The sampling technique used to select the two public health facilities (Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH) and Department of Health Services Tuberculosis and Leprosy Unit (DHSTLCU)) was a multi-stage sampling technique. Stage I: Selection of Nnewi North L.G.A. by purposive sampling technique from a sampling frame of 21 L.G.As in Anambra State because the Principal Investigator works in Nnewi North LGA at Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH). Stage II: Selection by simple random sampling technique of two public health facilities health facilities that provide DOTS services for the past six years and registered with Anambra State Ministry of Health.iii. Study Population:The study population were tuberculosis patients that accessed anti-tuberculosis care in Nnewi North Local Government Area at NAUTH and DHSTLCU from the period of 2007 to 2010 (a four year period). iv. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Only health facilities registered with the Anambra State Ministry of Health and have been providing Directly Observed Therapy Short course (DOTS) services for treating TB for the past six years were enlisted for the study. Patient treatment cards with information on any of the six treatment outcomes according to the WHO [10] and Treatment Success rate outcome according to Maimela [22], socio-demographics (that is, age, sex and HIV status) and year of treatment initiation and category of DOTS administered were evaluated. Any health facility not registered with the Anambra State Ministry of Health even though provided DOTS services in the last six years were excluded from the study. Also, patient treatment cards with inadequate documentation of the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. v. Study Design:A retrospective cohort study design was used to evaluate the treatment cards of TB patients accessing anti-tuberculosis for treatment outcome and determinants for the period of 2007-2010. Data set of the selected treatment cards that have information of inclusion criteria were extracted using a checklist. Information sought from the records included category of treatment and treatment outcomes according to WHO [21] (that is, any of the six outcomes of tuberculosis treatment which were cured, treatment failure, died, interrupted, defaulter and transferred-out) including success treatment outcome [22], socio-demographics including age, sex, HIV status and year of treatment initiation. vi. Definition of Terms: Treatment outcome definitions, adapted from an international standard classification, were as follows: (1) cured (a smear-positive patient based on the medical record, who had a negative sputum smear during the eighth month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion); (2) died (a patient who died during treatment irrespective of cause); (3) failed (a smear-positive patient who remained smear-positive at the fifth month of treatment); (4) defaulted (a patient who did not come back to complete chemotherapy and there was no evidence of cure through the sputum result during the fifth month of therapy), (5) treatment interruption (a patient who did not collect medications for 2 months or more at a particular time or at interval, but still come back for treatment and in the 8th month of treatment, the sputum result was positive), and (6) transferred out (a patient who was transferred to another treatment center and for whom treatment results are not known). [21] Another terminology hereby analysed, treatment success rate is the percentage of patients who are cured plus those who have completed treatment but without laboratory proof of cure, of new smear positive patients. [22]vii. Data Analysis:Data was analysed using computer software package SPSS version 17. Results of variables were represented in tables and tests of statistical significance carried out using appropriate tests of Multivariate Logistic Regression, with statistical significance set at p value < 0.05.viii. Ethical Approval:Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Nnamdi Azikiwe University/ Teaching Hospital Ethical Committee (NAU/NAUTHEC). Permission to conduct this study was obtained from heads of the two DOTS facilities in Nnewi North Local Government Area.

3. Results

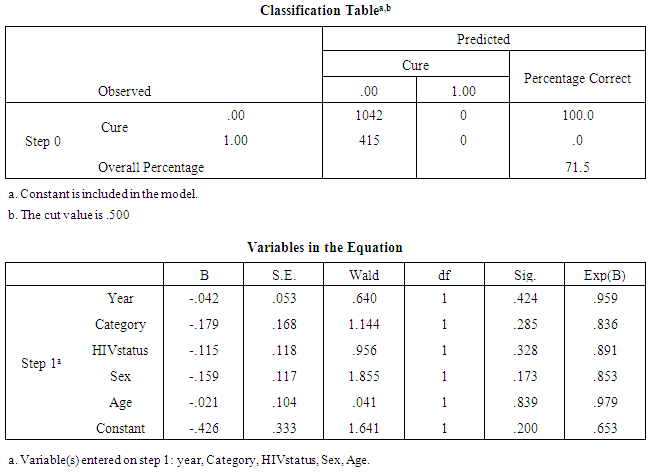

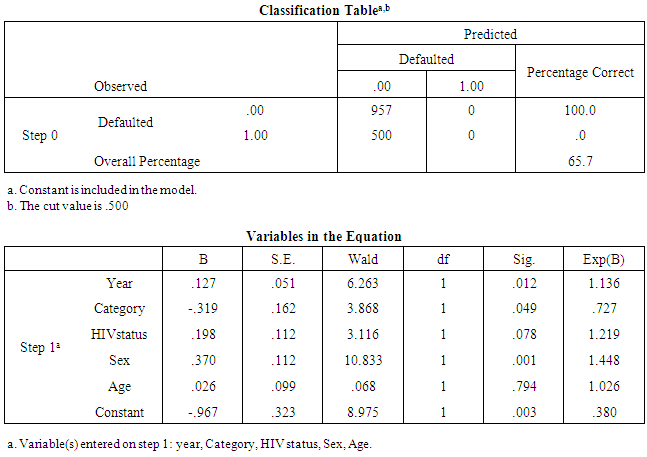

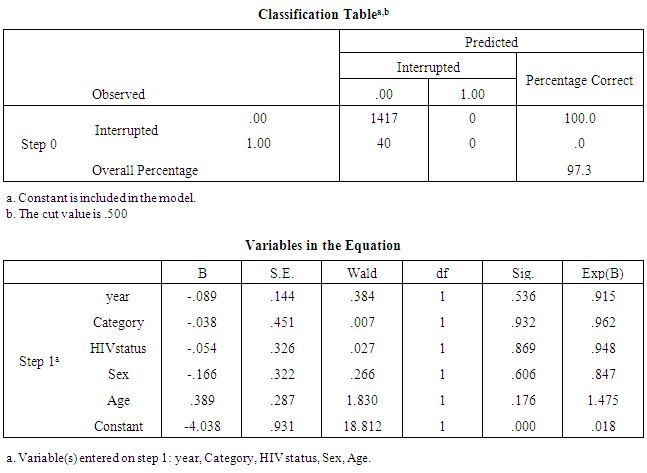

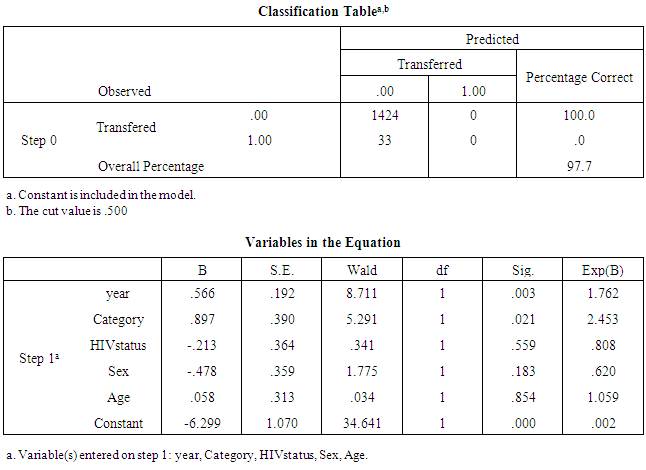

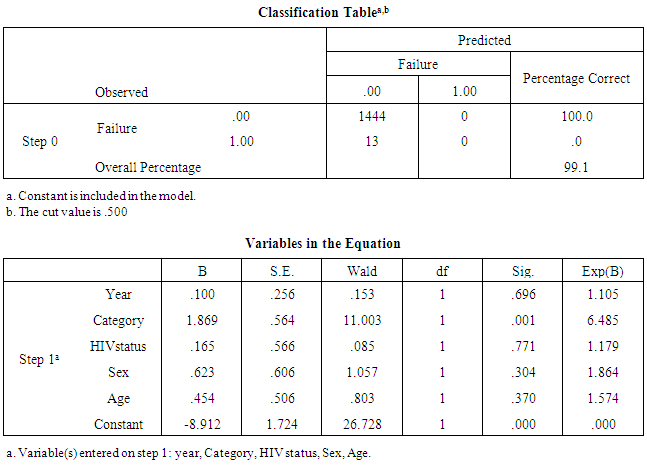

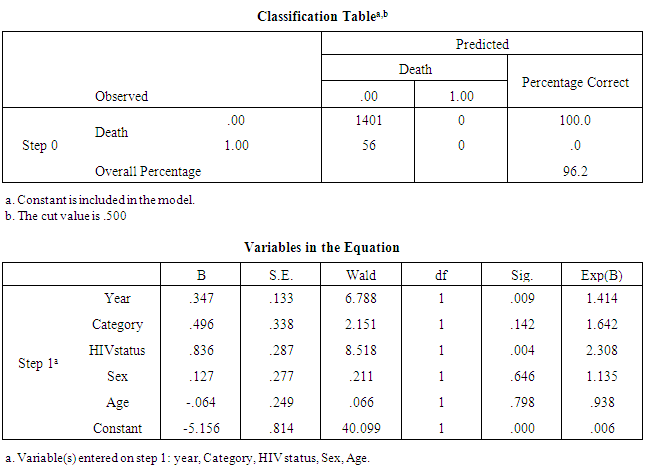

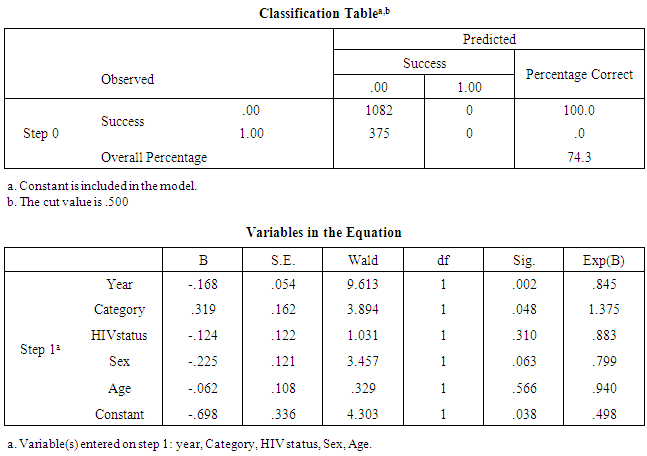

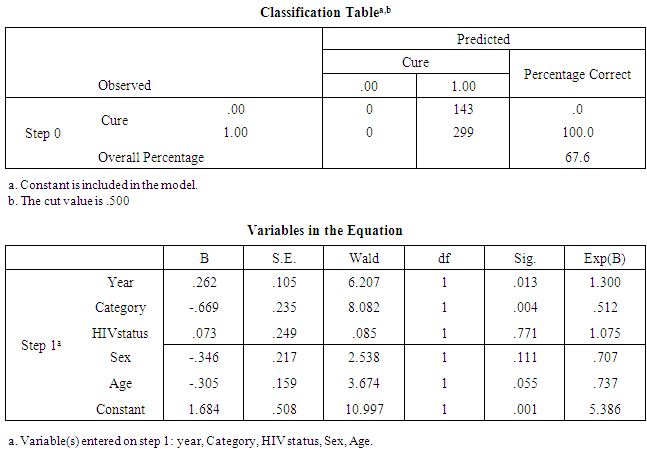

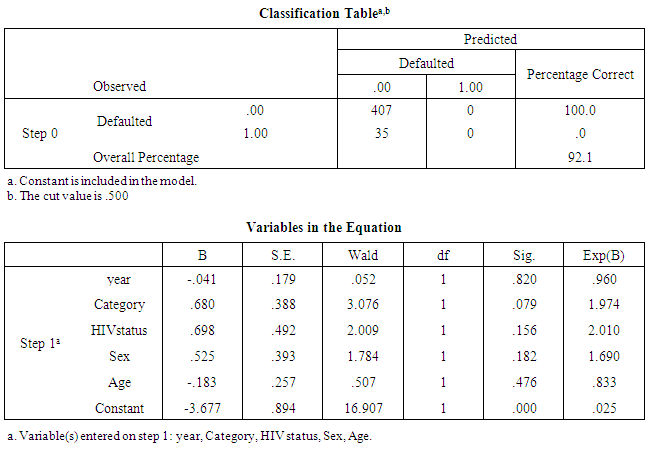

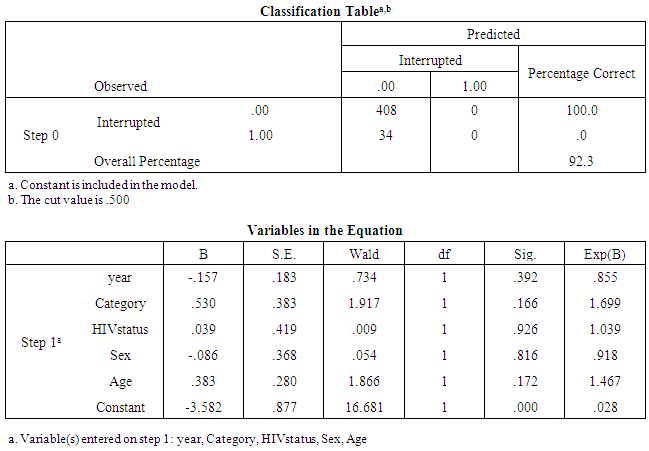

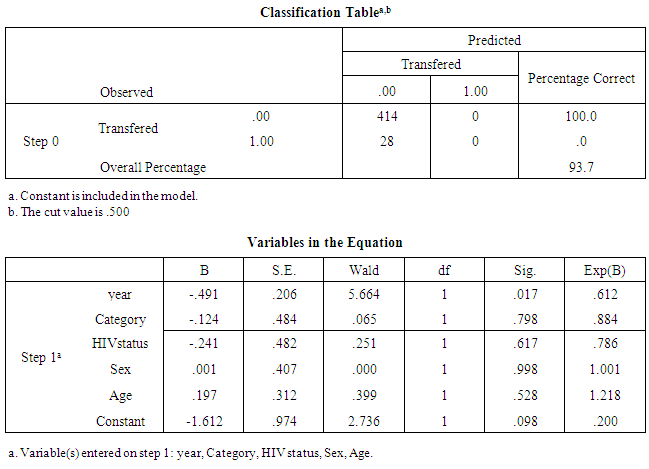

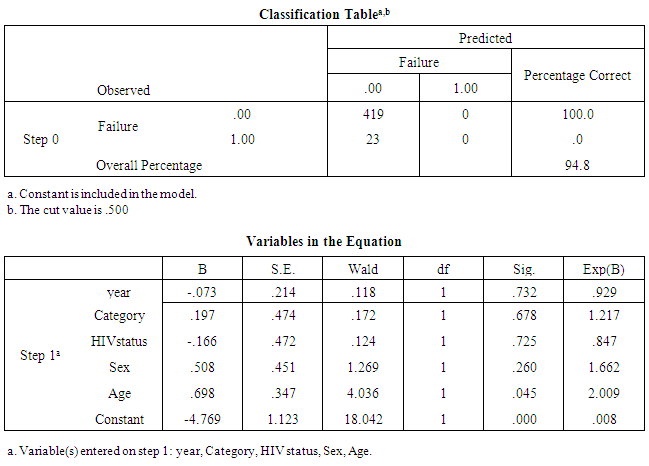

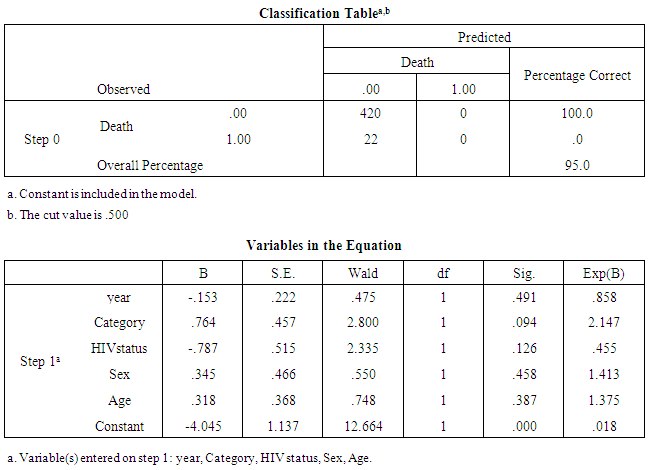

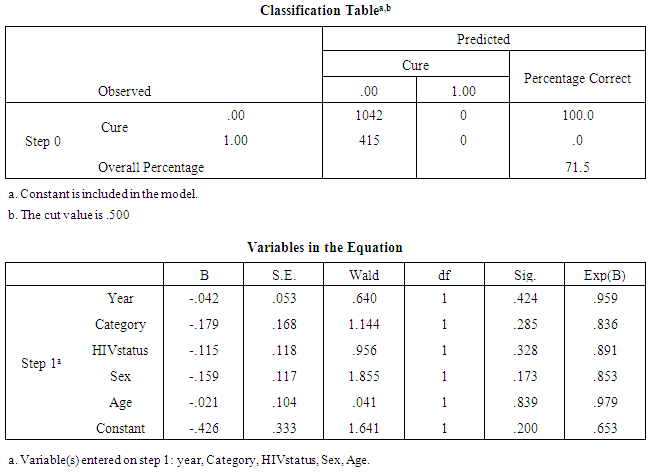

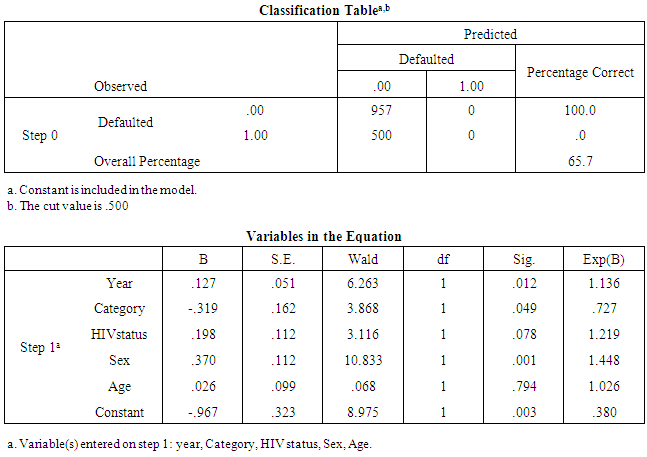

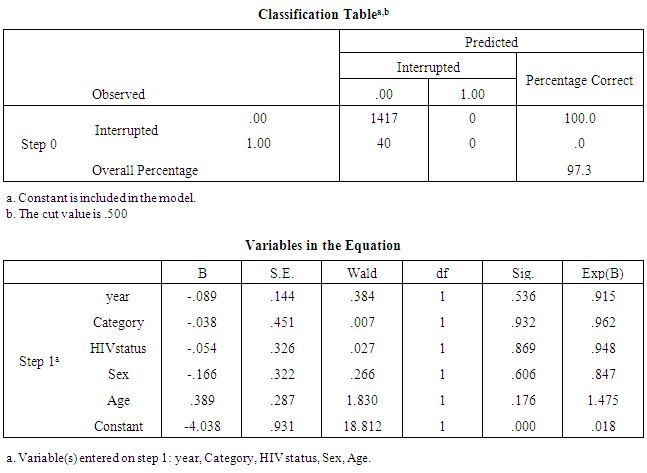

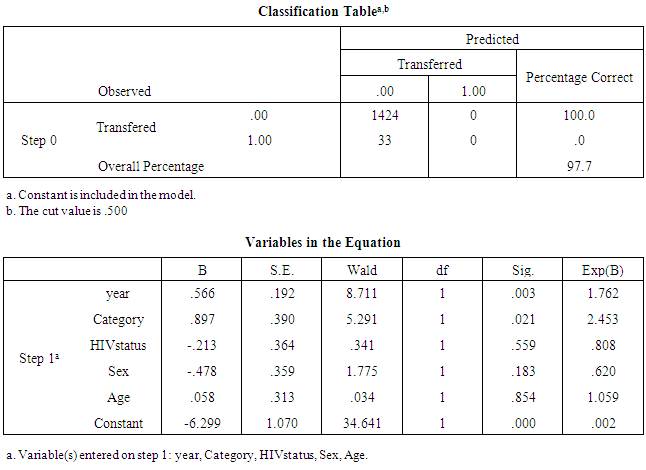

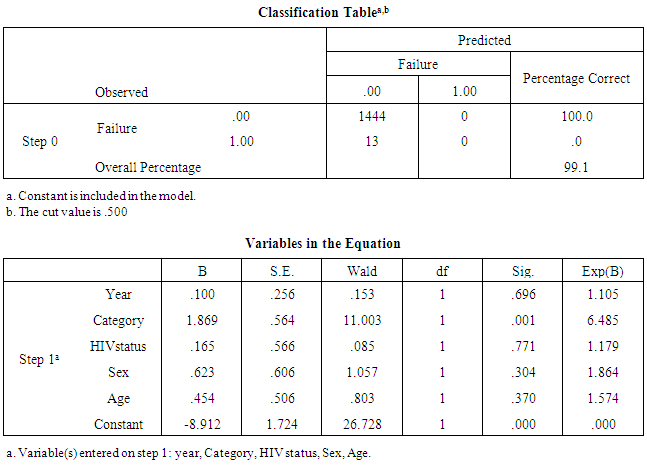

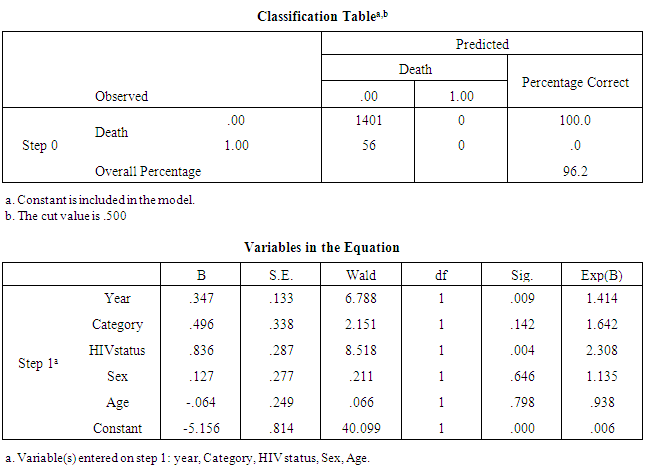

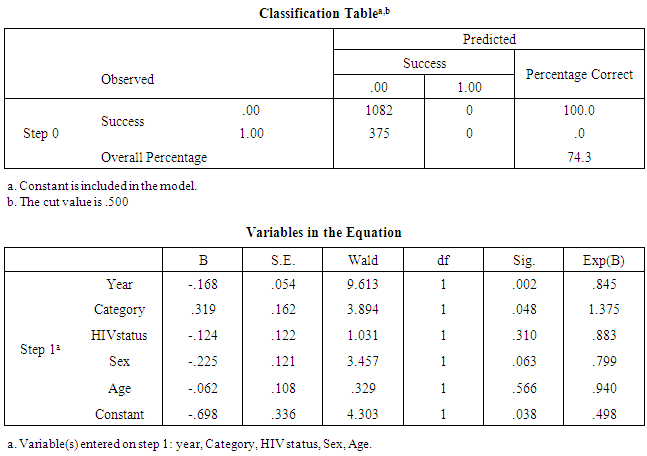

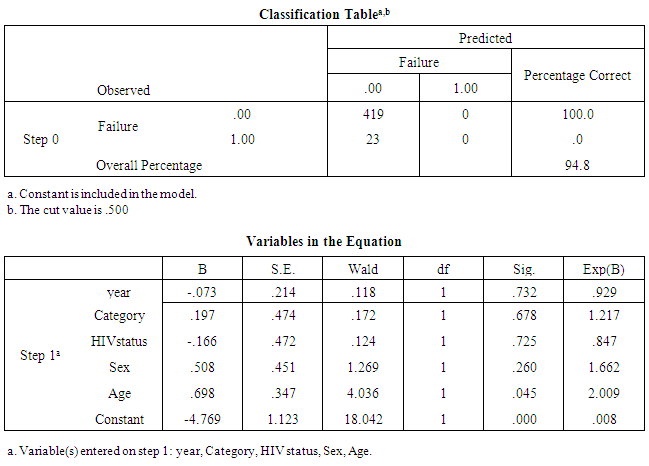

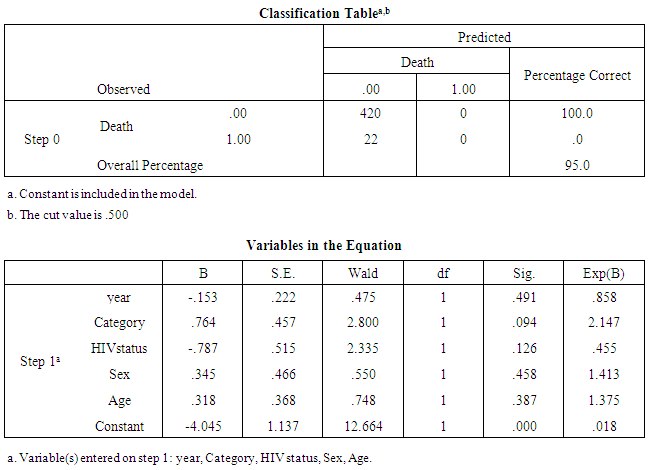

A total of 2,018 patients (1,899 patients in public health facilities and 119 in private health facilities) with the were reviewed with mean age of 34.0±4.2 years and majority males 60.0% (1100 patients) and 75% (90 patients) at public and private health facilities respectively. All patients were of Igbo origin. The determinants (covariates), following use of Multivariate Logistic Regression analysis for the different TB-DOTS treatment outcome of the public and private health facilities, showed that in the public health facilities 37.6% (714 patients) were cured without statistical significant difference traceable to any of the five covariates (year, category of DOTS treatment, HIV status, Sex and Age (see Table 1); 34.3% (500 patients) defaulted treatment with statistical significant difference contributed to by covariates of year ,category of DOTS treatment and sex corresponding to p-values at 0.012, 0.049 and 0.001 respectively(see Table 2); 2.7% (40 patients) interrupted their treatment with none of the five covariates contributing statistically significantly to treatment interrupted rate outcome(see Table 3); 2.3% (33 patients ) were transferred-out of NAUTH with covariates of year and category of DOTS treatment contributing statistically significantly with p-values of 0.003 and 0.021 respectively(see Table 4); 9% (13 patients) failed treatment with the covariate of category of treatment contributing statistically significantly with p-value of 0.001(see Table 5); 3.8% (56 patients) died with covariates of year and HIV status of patients contributing statistically significantly with p-value of 0.009 and 0.004 respectively(see Table 6); 25.5% (375 patients) treated successfully with covariates of year and category of treatment contributing statistically significantly with p-value of 0.002 and 0.048 respectively (see table 7). The determinants (covariates) responsible for the different treatment outcomes of DHSTLCU (hospital 2) , 67.6% (299 patients) were cured of TB with covariates year and category of treatment contributing statistically significantly with p-values of 0.013 and 0.004 respectively (see Table 8); 7.9% (35 patients) were defaulters with none of the five covariates contributing statistically significantly (see Table 9); 7.7% (34 patients) interrupted treatment with none of the five covariates contributing statistically significantly(see Table 10); 6.3% (28 patients) were transferred-out with only covariate of year contributing statistically significantly with p-value of 0.017 (see Table 11); 5.2% (23 patients) were failed treatment with only covariate of age contributing statistically significantly with p-value of 0.045 (see Table 12); 5% (22 patients) died during treatment with none of the covariates contributing statistically significantly(see Table 13).NAUTH (Hospital 1)Table 1. Logistic Regression of determinants of cured rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for cured patients it was observed that only 28.5% (415 patients) were cured. The covariates were found to be insignificant to the cure rate outcome.Table 2. Logistic Regression of determinants of Defaulter rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for defaulted patients it was observed that only 34.3% (500 patients) defaulted during observation. It was observe that year, category and sex contributed significantly to the status of defaulted patients with a corresponding p-value= 0.012, 0.049, and 0.001 respectively.Table 3. Logistic Regression of determinants of Treatment Interrupted rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for interrupted patients it was observed that only 2.7% (40 patients) interrupted their medication. The covariates were found to be insignificant to the interruption rate outcome.Table 4. Logistic Regression of determinants of Transferred-out rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for transferred patients it was observed that only 2.3% (33 patients) were transferred from the facility. It was equally, observed that year and category of treatment contributed significantly to the transferred out rate outcome with a corresponding p-value of 0.003 and 0.021 respectively assuming 95% CI.Table 5. Logistic Regression of determinants of Treatment Failure rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for failed patients it was observed that only 0.9% (13 patients) failed during the observation period. It was denoted that category of treatment contributed significantly to the status of failed rate outcome with a p-value of 0.001.Table 6. Logistic Regression of determinants of Death rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for dead patients it was observed that only 3.8% (56 patients) died during the observation period. It was observed that year and HIV status contributed significantly to the death rate outcome with a corresponding p-value of 0.009 and 0.004 respectively.Table 7. Logistic Regression of determinants of Success rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

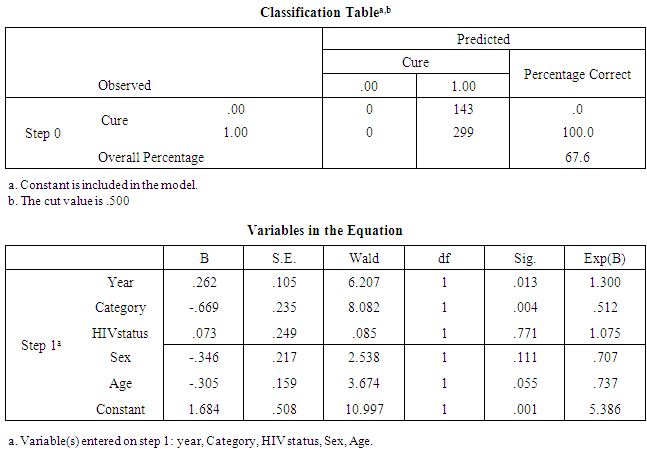

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for successful patients it was observed that only 25.7% (375 patients) were successful during the observed period. It was observed that year and category of treatment contributed significantly to the success status of the patients with a corresponding p-value of 0.002 and 0.048 respectively.Department of Health Services Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Unit (DHSTLCU)/ Hospital 2 Table 8. Logistic Regression of determinants of cured rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for cured rate outcome it was observed that only 32.4% (299 patients) were cured. It was observed that year and category of treatment contributed to the significance of the model with corresponding p-value of 0.013 and 0.004 respectively.Table 9. Logistic Regression of determinants of Defaulted rate outcome (2007-2010)

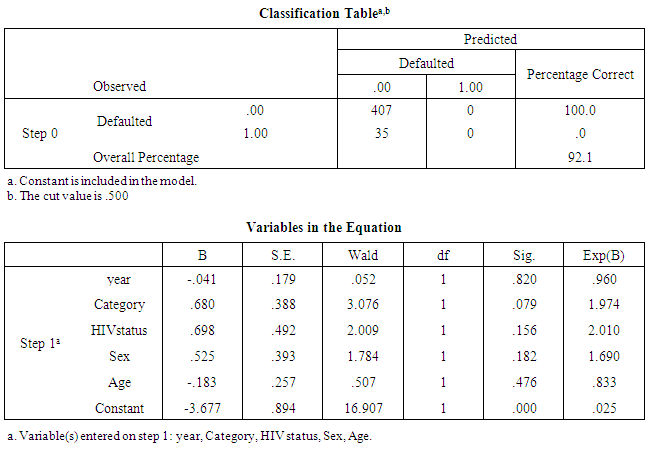

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for defaulted patients it was observed that only 7.9% (35 patients) defaulted. The covariates were found to be insignificant to the default rate outcome.Table 10. Logistic Regression of determinants of Treatment Interrupted rate outcome (2007-2010)

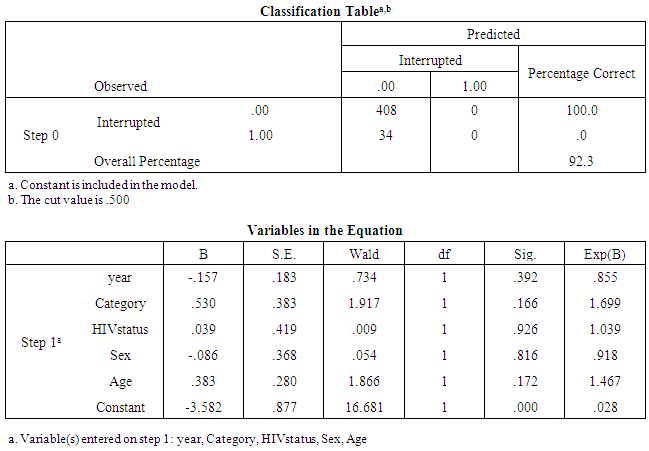

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for interrupted rate outcome it was observed that only 7.7% (34 patients) interrupted their treatment. The covariates were found to be insignificant to the interruption rate outcome.Table 11. Logistic Regression of determinants of Transferred-Out rate outcome (2007-2010)

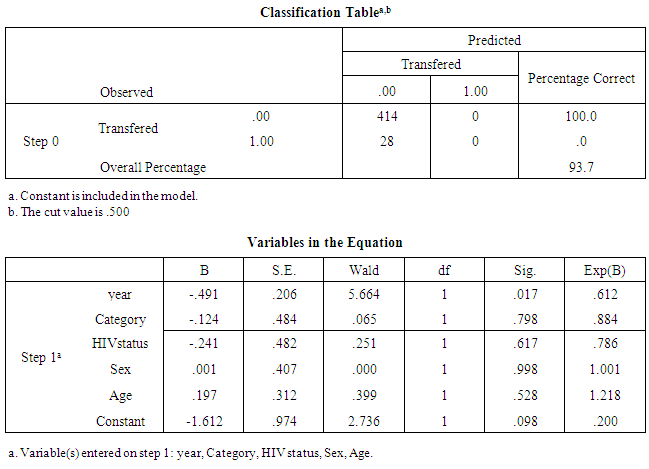

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for transferred out rate outcome it was observed that only 6.3% (28 patients) were transferred out from the facility. It was observed that year contributed to the transferred out rate outcome with a p-value= 0.017.Table 12. Logistic Regression of determinants of Treatment Failure rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for failed rate outcome it was observed that only 5.2% (23 patients) failed. It was observed that only the covariate of Age contributed to the failed rate outcome with a p-value of 0.045.Table 13. Logistic Regression of determinants of Death rate outcome (2007-2010)

|

| |

|

Interpretation: From the logistic Regression result for dead patients it was observed that only 5.0% (22 patients) died. The covariates where found to be insignificant to the death rate outcome.

4. Discussion

Any treatment outcome in which a cure is not established will pose a danger to the community, hence, prevention of such occurrences is necessary to maximize the efficiency of TB control programmes. The finding that the patients had mean age of 35.0±3.3 years is consistent with the age range reported by a study in Eastern Nigeria. [11] Also, the observation that a greater percentage of the patients in the cohort for NAUTH and DHSTCLU was male is consistent with other reports. [25, 26] The determinants of TB cured treatment outcome is nil of the five covariates at NAUTH while at DHSTLCU they are year and category of DOTS treatment. The implication of this may mean that the NAUTH facility more than DHSTLCU facility had robust human and material resources throughout the four year period under review and most of patients accessing care there complied with treatment. This is consistent with the report of a study conducted in DOTS centre in University College Hospital, Ibadan. [7] The unsuccessful treatment outcome for the two health facilities (defaulted, interrupted, transferred-out, failed and died) had determinants ranging from year, category, sex, HIV status and age. This finding is in keeping with reports by others. [5-11] The cure rate of 28.1 % and 67.1 % of NAUTH and DHSTLCU respectively found in this study are below the recommended target of 85% by the WHO. [4] More so, cure rate of NAUTH is lower than that reported (57.7%) by a study in a similar setting in eastern Nigeria. [11] An interesting finding of cure rate of 67.6% at DHSTLCU underscores the mainstreaming of community participation. [16] More so, the cure rate was much better than that (14.4 %) obtained by a study in similar setting. [27] Treatment failure rate at NAUTH (0.9 %) was better than that of DHSTLCU (5.2%). This could be attributable to specialist care more accessible at NAUTH. Treatment success rate at NAUTH was 25.7%.This study has several major limitations. It was retrospective and based only on data that was available public health records. We could not independently verify the accuracy of these records, nor could we collect additional data needed to confirm or refute our findings. This impacts variables such as those measuring the presence of an adverse event. We have no detail information of every patient in this study. However, this is beyond our control. Also, because of the difficulty of contacting patients with unsuccessful treatment outcome, our study could not address some of the factors leading to unsuccessful treatment outcome. Nevertheless, our findings are applicable to the current situation of TB control in public mix in Nigeria and African population, and may draw attention to major factors influencing unsuccessful treatment outcome in the management and control of TB.

5. Conclusions

Determinants of treatment outcomes at NAUTH were year, category of treatment, sex and HIV status of patient while at DHSTBLU, the determinants were year, category of treatment and age. Further research to focus on the determinants for disaggregated respective four years, identify centre-specific factors associated with poor treatment outcome, emphasise the place of treatment success rate and analyse primary data set using administered questionnaire for comprehensiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate all the four research assistants that worked tirelessly to collect data for this research.

References

| [1] | WHO. Global TB Control Report; Surveillance, Planning, Finance; 2007 [cited 2013 April 24]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int. |

| [2] | Stop TB partnership. Available from: www.Stoptb.org/stop_tb_initiative/amsterdam_conference/Nigeria_speech. Asp (cited November 24, 2012). |

| [3] | Wobester W, Yuan L, Naus M. The tuberculosis treatment completion study group. Outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis treatment in the tertiary care setting- Toronto 1992/93. CMAJ 1999; 160 : 789-794 |

| [4] | WHO .Global tuberculosis control (rep no WHO /TB/97.225). Geneva: WHO; 1997: 9-15. |

| [5] | Servin T, Atac G, Gungor G. Treatment outcome of relapse and defaulter pulmonary tuberculosis patients. In J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002; 6: 320-325. |

| [6] | Brudney K, Dobkin J. Resurgent tuberculosis in New York city. Human Immunodeficiency virus, homelessness and the decline of Tuberculosis control programs. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 144: 745-749. |

| [7] | Grzybowsky S, Enaarson D. Results in Pulmonary tuberculosis patients under various treatment programs condition [in French]. Bull Int Union tuberculosis 1978; 53: 70-75. |

| [8] | Antonie D, French CE, Jones J, Watson JM. Tuberculosis treatment outcome monitoring in England, Wales and Northern Ireland for cases reported in 2001. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007; 61 : 302-307. |

| [9] | Sumartojo E. When tuberculosis treatment fails: A social behaviour account of patients’ adherence. American Review of Respiratory Disease 1993; 147: 1311-1320. |

| [10] | Fatiregun AA, Ojo AS, Bamgboye AE. Treatment outcomes among pulmonary tuberculosis patients at treatment centers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med [serial online] 2009 [cited 2012 Dec 31];8:100-4. Available from:http://www.annalsafrmed.org/text.asp?2009/8/2/100/56237. |

| [11] | Ukwuaja KN, Ifebunadu NA, Osakwe PC, Alobu I. Tuberculosis Treatment Outcome and its Determinants in a Tertiary care setting in Southeastern Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J.2013 Jun; 20(2): 125-129. |

| [12] | Efegbere HA, Anyabolu AE , Onyeyili AN, Efegbere EK, Sani-Gwarzo N, Omoniyi A, Okonkwo RC, Eze OP, Oguwuike MU, Enemuo EH, Adogu PO, Ilika AL , Igwegbe AO, Oyeka IC . Determinants of treatment outcome of public- private mix tuberculosis control programme in South-Eastern Nigeria. AFRIMEDIC Journal 2014; Vol 5(1): 25-37. |

| [13] | Efegbere HA, Anyabolu AE , Efegbere EK, Sani-Gwarzo N, Omoniyi A, Okonkwo RC, Eze OP, Oguwuike MU, Enemuo EH, Adogu PO, Ilika AL , Igwegbe AO, Oyeka IC . Effectiveness of treatment outcomes of public-private mix tuberculosis control programme in Eastern Nigeria. Vol 4(1): 18-22 |

| [14] | Cox H, Kebede Y, Allamuratova S, et al. Tuberculosis recurrence and mortality after successful treatment: Impact of drug resistance. PLoS Med. |

| [15] | WHO .Global TB Control: Surveillance, planning, financing. Geneva.2002; WHO; WHO/CDC/TB/2002.295. |

| [16] | WHO Community Contribution to TB Care; Practice and Policy 2003; WHO/ CDC/ TB/2003.312. [cited 2012 September 26] Available from URL: http://www.who.int. |

| [17] | WHO .Guidelines for Implementing Community TB Care Programme; 2004[cited 2013 Apr 22]. Available from URL: http://afro.who.int/tb/respub/regional_guidelines_for _ctbc_ programs.pdf. |

| [18] | Kironde S, Kahirimbanji M. Community participation in primary health care programmes: Lessons from treatment delivery in South Africa; Afr Health Sci. 2002; 2(1): 16-23. |

| [19] | Gai R, Xu L, Wang X, Liu Z, Cheng J, Zhou C et al. The role of village doctors on tuberculosis control and DOTS strategy in Shandong Province, China. Bio Science Trends 2008; 2: 181-186. |

| [20] | Federal Ministry of Health .National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control program. Revised Workers manual 5th edn., 2008 : 1-227. |

| [21] | Federal Government of Nigeria .National Population Commission: Census 2006. |

| [22] | Anambra State Government of Nigeria. Ministry of Health Awka, 2013. |

| [23] | International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Tuberculosis guide for low income countries.4th ed. Paris: IUATLD; 1996. |

| [24] | Maimela E. Evaluation of Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and the determinants of treatment failures in the Eastern Cape Province (2003-2005). A thesis presented to University of Pretoria, South Africa.2009. |

| [25] | Salami AK, Oluboyo PO. Management outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis: A nine year review in Ilorin. West Afr J Med 2003;22:114-9. [PUBMED] |

| [26] | Scholten JN, Fujiwara PI, Frieden TR. Prevalence and factors associated with tuberculosis infection among new school entrants, New York City, 1991-1993. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis 1999;3:31-41. |

| [27] | Amoran OE. Determinants of Treatment Failure Among Tuberculosis patients on Directly Observed Therapy Short course in Rural Primary Health Care centres in Ogun State, Nigeria: Open Access 2011: 104.doi:10.4172/phcoa.1000104. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML