-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2015; 5(4): 181-189

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20150504.07

Factors Affecting Antihypertensive Medications Adherence among Hypertensive Patients in Saudi Arabia

Fatmah Alsolami1, 2, Ignacio Correa-Velez1, Xiang-Yu Hou1

1School of Public Health and Social Work, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of technology, Brisbane, State of Queensland, Australia

2Faculty of Nursing, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Fatmah Alsolami, School of Public Health and Social Work, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of technology, Brisbane, State of Queensland, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Hypertension is a health problem that has increasing prevalence worldwide. Antihypertensive medications are the key for achieving controlled blood pressure. Little is known about predictors of antihypertensive medications adherence in Saudi Arabia. This is a cross-sectional study of 308 participants from a general hospital in Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia conducted between July 2013 and February 2014. Out of the 308 participants, the results showed that 27.9% were classified as perfect adherents and 72.1% were classified as non-perfect adherents to antihypertensive medications. Significant predictors of non-perfect antihypertensive medications in this study were having non-formal education (p=0.031, OR=2.3, 95%CI = [1.82-5]), reporting a poor relationship with physicians (p=0.004, OR=2.25, 95%CI= [1.29-3.9]), and having no co-morbidities (p=0.048, OR=1.86, 95%CI [1.00-3.46]). The outcome of this study highlights the need for policies and interventions that enhance the level of formal education at a population level and improve physician-patient relationships in health care settings.

Keywords: Antihypertensive, Medications, Adherence, Saudi Arabia

Cite this paper: Fatmah Alsolami, Ignacio Correa-Velez, Xiang-Yu Hou, Factors Affecting Antihypertensive Medications Adherence among Hypertensive Patients in Saudi Arabia, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 181-189. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150504.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hypertension is a global health problem, and its prevalence is still increasing. In 2000, it was estimated that one billion people suffered from hypertension, and this number is predicted to increase to 1.56 billion by 2025 (Kearney et al., 2005). Follow-up and medication adjustments should continue until the goal of blood pressure (BP) lower than 140/90 mmHg is achieved. This is the level required to decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease complications. The goal for patients with hypertension and co-morbidities such as diabetes or renal disease is to achieve a BP lower than 130/80 mmHg. Follow-up visits for stable individuals who have reached their BP goals usually occur at 3 to 6-month intervals (Chobanian et al., 2003).The use of antihypertensive medications is a key component of the long-term approach to controlling BP levels. The effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment is well established and has been quantified in terms of overall reduction in the relative risk of stroke and other cardiovascular disease events as well as lower healthcare costs (Dragomir et al., 2010). Adherence to antihypertensive medication is an effective step for controlling blood pressure and preventing complications. Low-adherent patients have a higher risk of cardiovascular events than high-adherent patients (Mazzaglia et al., 2009). A cohort study of 59,647 hypertensive patients living in Quebec, Canada, showed that poor adherence to antihypertensive medication is correlated to a high risk of hospitalization and higher healthcare costs, which could be as much as USD $3,574 (95% CI, $2897–$4249) per person within a three-year period (Dragomir et al., 2010).There are several factors that affect a hypertensive patient’s behavior regarding adherence to antihypertensive treatments. These factors can be categorized as: (1) patient-related factors such as socio-demographics, beliefs about treatment and knowledge about hypertension and its treatment; and (2) patient-provider factors such as the patient-provider relationship and the support received from healthcare services (Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Van Oppen, Van Marwijk, De Beurs, & Van Dyck, 2004). A study of 250 Iranian patients in Shiraz investigating the impact of socio-demographic factors on their medication adherence found that patients who were older than 45 years were more likely to adhere to antihypertensive regimens and also to have better knowledge of their condition compared to those who had low knowledge about their health condition (Hadi & Rostami-Gooran, 2004). There is a positive relationship between levels of adherence and knowledge regarding treatment (Hayrettin et al., 2009). In a study in Saudi Arabia, it was found that 43.7% of 190 patients believed they could stop taking antihypertensive drugs once their blood pressure had stabilized. This demonstrates how a lack of knowledge and information regarding treatment can contribute to patient non-adherence (Al-Sowielem & Elzubier, 1998).When patients have positive beliefs regarding the efficacy of their treatment and also trust that their medication is working well to control their illness, their adherence often improves (Fraser, Hadjimichael, & Vollmer, 2001; Holzemer et al., 1999). On the contrary, believing that medications are not important or are harmful is a barrier to adherence (Cohen, Rogers, Burke, & Beilin, 1998). The belief that taking antihypertensive medication will result in side effects is common among hypertensive patients (Cohen et al., 1998). Importantly, patients’ beliefs about medical management, and about drugs in particular, are not necessarily associated with their religious beliefs (Al-Sowielem & Elzubier, 1998) or cultural background (Li, Stewart, Stotts, & Froelicher, 2006). The presence of co-morbidities or uncontrolled blood pressure that requires a complex drug regimen can affect patients’ medication adherence. When compared with complex drug regimens, simpler regimens have been found to be associated with greater levels of patient adherence (Iskedjian et al., 2002). Furthermore, poor control of hypertension results in more frequent physician visits and higher drug costs (Paramore et al., 2001). The costs of medications have an inverse relationship with medication adherence (Paramore et al., 2001). The more expensive the medication, the less chance that some patients would be able to afford it. This results in poor blood pressure control due to no available treatment.Health education resources such as patient education sessions and written patient education materials, are provided by the healthcare system to enhance treatment practices. The aim of providing such resources is to increase patient knowledge about their health condition and the required management. However, compared to no active intervention, the clinically significant effect of printed educational materials on adherence appears to be minor (Farmer et al., 2008). The level of satisfaction and degree of autonomy patients experience when they deal with healthcare providers is determined by the quality of the therapeutic relationship (Armstrong, 2010). Patients may perceive that the healthcare environment is not therapeutic if they feel dissatisfied with their relationship with healthcare providers. Poor relationships between patients and healthcare providers decrease patient empowerment and lead to lower levels of medication adherence (Safeer & Keenan, 2005).To date, limited literature exists on medication adherence and its predictors among antihypertensive patients in Saudi Arabia (AL-Rukban, Al-Sughair, Al-Bader, & Al-Tolaihi, 2007; Al-Sowielem & Elzubier, 1998; AlNozha, Ali, & Osman, 1997). Compliance to antihypertensive treatments was assessed in a cross-sectional study of 190 patients attending primary health care in Saudi Arabia. The results showed that 34.2% of patients were compliant with the recommended treatment (Al-Sowielem & Elzubier, 1998). A 2007 study which focused on the management of hypertension for Saudi patients receiving primary health care, reviewed the medical records of 201 patients and found that only 25% showed a controlled blood pressure. Findings from this study reflected inadequate physician practice with respect to patients with hypertension (AL-Rukban et al., 2007). In another study, a population-based cross-sectional survey of 13,700 hypertensive patients in Saudi Arabia reported that the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension (ISH), isolated diastolic hypertension (IDH) and systolic diastolic hypertension (SDH) among adults above 18 years was 1.8%, 3.8% and 3.5%, respectively (AlNozha et al., 1997). This paper reports on the findings of a study conducted between 2013 and 2014 which examined the levels of medication adherence and its predictors among 308 hypertensive patients attending outpatient clinics in a general hospital in Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Method

- Ethical approval was gained from the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee in Brisbane, Australia (approval number 1200000522) and King Fahad General Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (approval number 00163).

2.1. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

- The inclusion criteria for this study were (1) adult patients aged 18 years or older attending the outpatient clinics at King Fahad General Hospital (Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia); (2) who had a diagnosis of hypertension and had started their antihypertensive medication more than six months ago. Individuals who had been diagnosed with hypertension within the previous six months were excluded as they were likely to require frequent monitoring for medication adjustment to achieve a stable BP.

2.2. Study Design

- This cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2013 and February 2014. A total of 308 hypertensive patients were interviewed during the clinic hours (8 am to 2 pm weekdays) at the outpatient department, King Fahad General Hospital in Jeddah city. Convenience sampling was used by approaching all patients who visited outpatient clinics (cardiology, endocrinology, and internal medicine) for follow up with the treating physicians. Patients were invited to participate while visiting the nursing room to complete the initial assessment (pulse, blood pressure, temperature) prior to their medical appointment. The principal researcher explained the study to potential participants and those who agreed to participate were asked to sign a consent form. Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire in the waiting area after they completed their clinic visits; the principal researcher was available to answer any inquiries. For patients who could not read or write, the principal researcher and research assistants (two of the staff nurses in the treatment room) assisted them by reading the survey questions and response categories, and recording their answers in the questionnaire.

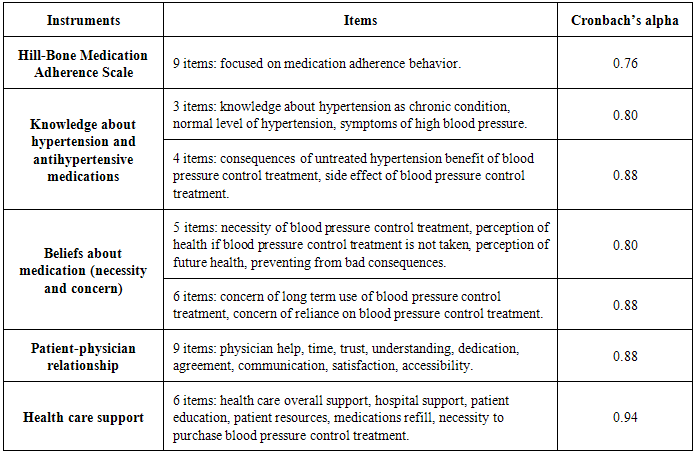

2.3. Research Instrument

- The instruments used to assess adherence to antihypertensive treatment and its related factors are shown in Table 1. To measure adherence level, an Arabic version of the Hill-Bone questionnaire was used. The Arabic version was validated in a previous study reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 (Alsolami, 2013). It includes nine questions with four response categories ranging from 1 = None of the time to 4 = All of the time.

|

3. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the socio-demographic, health-related and adherence-related variables. Bivariate analyses using the Pearson’s Chi-square test were employed to assess the association between the outcome measure (level of adherence) and each of the socio-demographic, health-related, and adherence-related variables. Adherence level was dichotomized into perfect adherence and imperfect adherence by grouping and coding the responses for “some of the time, most of the time and all of the time” as imperfect adherence, and “none of the time” responses as perfect adherence, based on a previous study that used the Hill-Bone questionnaire (Koschack, Marx, Schnakenberg, Kochen, & Himmel, 2010).Binary logistic regression analysis using the backward stepwise likelihood-ratio method was used to assess the predictors of adherence controlling for the socio-demographic factors (gender, age, marital status, education status, employment status, smoking status, income, and time since diagnosis of hypertension) which were fixed into the model. The final binary logistic regression model includes all the socio-demographic factors and the significant predictors of adherence. The alpha level of significance for all inferential statistics was set at 0.05. Overall model fit was estimated using the R2 statistic. SPSS v. 21 (SPSS IBM Statistics) was used to conduct all statistical analyses.

4. Results

- Of the 347 questionnaires that were distributed, 316 were returned, for a response rate of 85%. Eight of the returned questionnaires were incomplete and therefore this analysis is based on 308 completed questionnaires.

4.1. Participant’s Characteristics

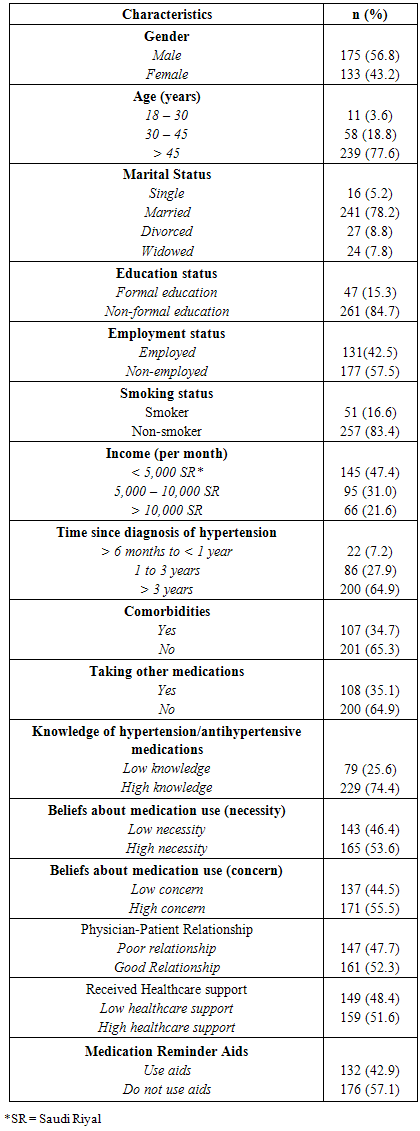

- The socio-demographic, health-related and adherence-related characteristics of participants in this study are shown in Table 2. The majority of participants were male (56.8%), older than 45 years (77.6%), married (78.2%), with non-formal education (84.7%), and non-smokers (83.4%). Those with non-formal education were mostly older patients who came to Jeddah city originally from rural villages and were illiterate or had learned basic reading and writing skills at the mosques. Almost half of respondents had an income lower than 5,000 Saudi Riyals [$1,350 USD].

|

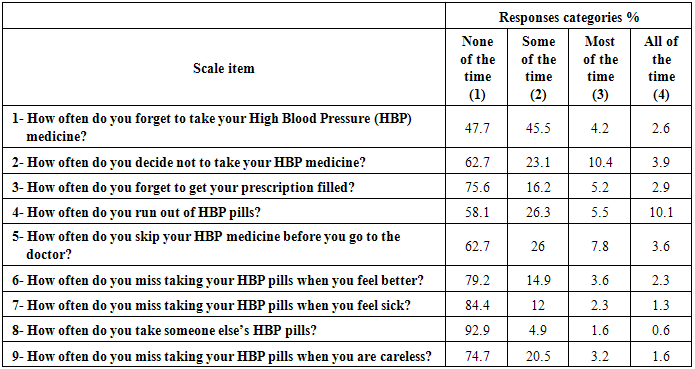

4.2. Adherence Level

- Table 3 reports the frequency of responses to the Hill-Bone scale items. The results show that out of the 308 patients who participated in this study, 27.9% were classified as reporting perfect adherence and 72.1% were classified as non-perfect adherence (Song et al., 2011).

|

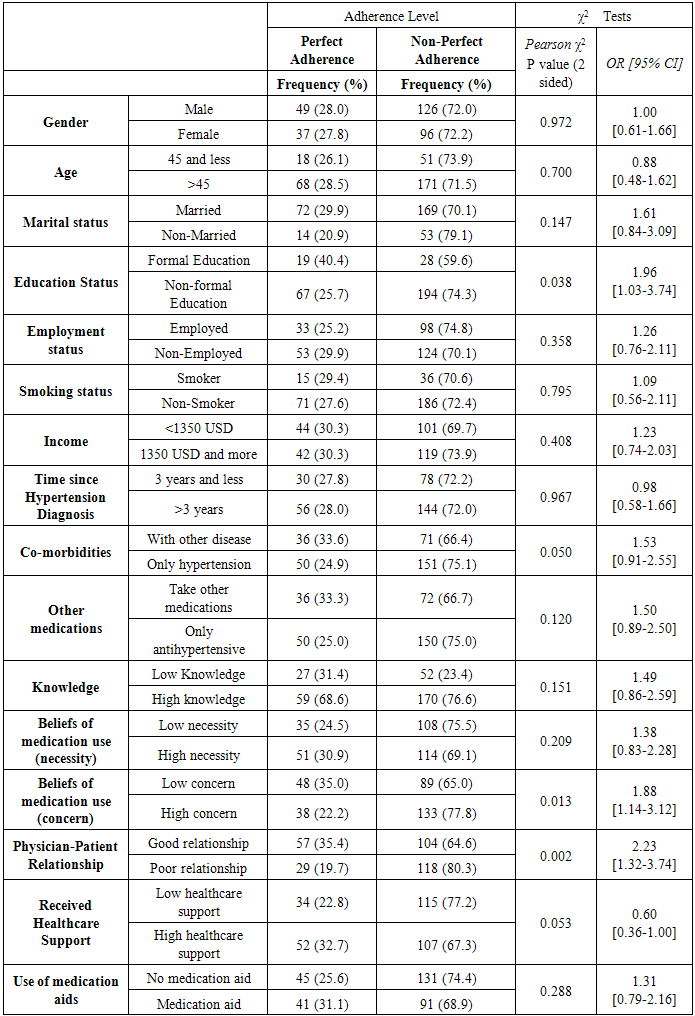

4.3. Bivariate Analysis

- Table 4 shows the bivariate associations between the level of adherence and each of the socio-demographic, health- and adherence-related factors. The bivariate analyses found that level of education, beliefs about medication (concern), the physician-patient relationship and co-morbidities were significantly associated to level of adherence. The odds of reporting none perfect adherence to antihypertensive treatments were 2.3 times greater among non-formally educated patients compared to those who received formal education, 1.89 times greater among patients who reported high level of concern about taking the medications compared to those with low concern, 2.25 times greater for those who reported poor relationship with their physicians compared to those who reported good relationship with their physicians and 1.86 greater with patients who only hypertension as a health condition to those with other co-morbidities.

|

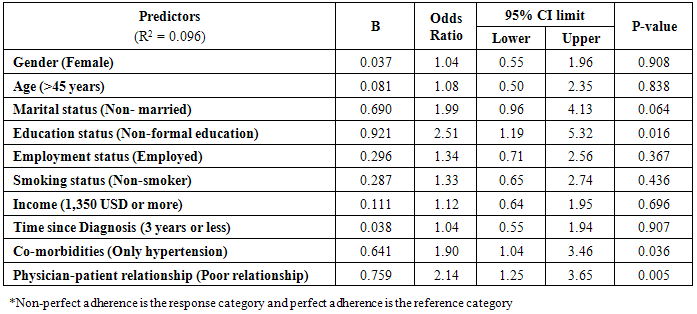

4.4. Regression Analysis

- A binary logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the predictors of medication adherence. All socio demographic characteristics were fixed in the model. The final model (Table 5) includes the socio-demographic characteristics and all the factors that reported significance (p<0.05). The Nagelkerke R2 was 0.096. Table 5 shows that having non-formal education (p=0.031, OR=2.3, 95%CI = [1.82-5]), reporting a poor relationship with their physicians (p=0.004, OR=2.25, 95%CI= [1.29-3.9]), and having no co-morbidities (p=0.048, OR=1.86, 95%CI [1.00-3.46]) were significant predictors of non-perfect adherence, after controlling for all the other factors in the model.

|

5. Discussion

- For patients with high blood pressure, adherence to medication is a significant factor in preventing damaging complications to body systems. The literature has identified several factors that contribute to a lack of adherence to antihypertensive medication in hypertensive patients such as socio-demographic characteristics, physician-patient relationship and health care support. Addressing these factors is a significant step towards the successful control and management of hypertension.Very limited research has investigated adherence to antihypertensive medication and its associated factors in Middle Eastern countries in general and in Saudi Arabia in particular. The present study has addressed this research gap by investigating the levels of medication adherence and its predictors among 308 hypertensive patients attending an outpatient hospital clinic in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. In our study, 72% of the participants reported non-perfect adherence to their medications. These results are higher than those from previous studies conducted in Tabuk City, Saudi Arabia (47.0%) (Khalil & Elzubier, 1997), Palestine (54.2%) (Al-Ramahi, 2013), Egypt (25.9%) (Youssef & Moubarak, 2002) and Pakistan (64.7%) (Saleem et al., 2012). The difference in our results can be explained by the different methodologies used, study population and settings. Previous studies used yes/no responses for adherence questions (Song et al., 2011), which reduces the range of responses for participants. Other studies used the pill-counting method (Chin, 2001) and pharmacy records (Koschack et al., 2010). The results from the current study are based on patients’ self-reports using a Likert (Hill-Bone) scale to assess medication adherence. This scale has been developed specifically to measure the level of adherence for hypertensive patients (Lambert et al., 2002). The scale testing reported high level of validity and reliability in different studies (Kim, Hill, Bone, & Levine, 2000; Lambert et al., 2002; Song et al., 2011).This study focused on both patient- and patient-provider related factors and found that non-formal education, absence of co-morbidities, and poor physician-patient relationship were significant predictors of non-perfect adherence. The significant association found between patients’ education level and medication adherence is in line with previous studies in Saudi Arabia and internationally (Baune, Aljeesh, & Bender, 2005; Hashmi et al., 2007), where patients with formal education reported a higher level of medication adherence compared to those with non-formal education. Patients with greater levels of formal education may have a better understanding of the goal of controlling their blood pressure, the consequences of poor adherence and the potential side effects associated with antihypertensive treatments.We also found that the absence of co-morbidities predicted non-perfect adherence among this group of patients. Similarly, previous studies in the U.S. found that patients with both hypertension and diabetes were more likely to adhere to multiple medications (An & Nichol, 2013; Loeppke et al., 2011). This is because of their experience with multiple symptoms from hypertension and other co-morbid conditions which requires them to adhere to their medications to relieve these symptoms. Consistent with previous studies (Aljumah, Ahmad, & AlQhatani, 2014), we found a significant association between poor physician-patient relationship and non-perfect medication adherence. Good physician-patient relationship is associated with better medication adherence. In the outpatient clinics in general hospitals in Saudi Arabia, there is very limited chance for patients to be seen by the same physician on every visit, as consultations may be provided by a number of physicians or medical graduates under the supervision of a senior physician. Given the high volume of consultations, patients who wish to be seen by the same physician are likely to be placed on a waiting list. Lack of continuity of care prevents the establishment of quality long-term relationships between patients and healthcare providers. According to Thom and other colleagues, building physician-patient trust is underpinned by patient’s receiving clear communication and the expectation of a long-term relationship (Thom, Kravitz, Bell, Krupat, & Azari, 2002). Although some attempts have been made to explore physician-patient communication in Saudi Arabia, there is a scarcity of quality research investigating this issue and its impact on medication adherence. This is an important gap given the potential impact of culture, education and health beliefs on the quality of physician-patient relationships. The findings of our study showed that patient’s beliefs about antihypertensive medications were not significant predictor of medications adherence. Patients’ knowledge about their health condition tends to determine their beliefs about treatment and medication, and when healthcare providers fail to provide relevant information or education support to hypertensive patients related to the medications, patients’ beliefs about the necessity of taking medications decreases and their level of concern increases.Our results showed a not statistically significant association between knowledge of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment, and medication adherence. This is contrary to the findings from other study which found that knowledge is a significant predictor of adherence to antihypertensive treatment (Williams, Baker, Parker, & Nurss, 1998). However, the use of educational interventions to increase patients' knowledge about hypertension and the antihypertensive treatment have failed to show a significant impact on patients’ medication adherence practice (Amado Guirado, Pujol Ribera, Pacheco Huergo, Borras, & Grp, 2011; Hayrettin Karaeren et al., 2009). A study of 227 hypertensive patients in Turkey showed that having greater knowledge of the side effects of antihypertensive treatments can lead to a reduction in adherence (Karaeren et al., 2009). Increasing patient’s knowledge about their health condition and treatment may change patient’s behavior, but patients require time to adjust before these behavioral changes, such as improved adherence, can be observed (Magadza, Radloff, & Srinivas, 2009).Previous studies on antihypertensive treatment adherence have also assessed the impact of time since diagnosis on medication adherence (Caro, Salas, Speckman, Raggio, & Jackson, 1999; Mazzaglia et al., 2009). These studies have shown that newly diagnosed patients with hypertension are more likely to report low level of adherence to their treatment (Mazzaglia et al., 2009). Recently diagnosed patients who have started a new treatment usually experience the unpleasant side effects of the medication, such an increase in the frequency of urination or light-headedness which can lead to poor medication adherence. The chronic nature of hypertension can also impact on patients’ ability to adapt to the regular and long-term use of medications. Our study however did not find a statistically significant association between time since diagnosis and medication adherence in this population group. The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this was a small non-random sample of patients attending an outpatient clinic in a general hospital and therefore findings cannot be generalized to the overall population of hypertensive patients in Saudi Arabia. Second, this survey was based on self-reports of patients regarding their medication adherence and under-reporting of non-adherence may have occurred (although higher levels of non-perfect adherence were found compared to previous studies). A more accurate picture of non-adherence to antihypertensive treatment can be obtained using additional methods such as accessing medical and pharmacy records. Also, the high proportion of non-formally educated patients in our study could have impacted on their understanding of the survey questions.

6. Conclusions

- Despite these limitations, this is the first study (to the best of our knowledge) that has assessed the predictors of medication adherence among hypertensive patients in Saudi Arabia. We have found that having non-formal education, absence of co-morbidities and a poor physician-patient relationship are significant predictors of non-adherence among this group of patients. These findings highlight the need for policies and interventions that enhance the level of formal education at a population level and improve physician-patient relationships in health care settings. Given the high prevalence of non-adherence reported in this study, further research is also needed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of interventions that can improve treatment adherence among hypertensive patients in Saudi Arabia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- A special thanks for Queensland University of Technology for their academic support during the conducting of this study. We thank the nursing staff in the outpatient departments in King Fahad General Hospital, who provided a supportive environment and facilitated the conducting of this research in the hospital.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML