Adogu P. O. U.1, Ubajaka C. F.1, Emelumadu O. F.1, Alutu C. O. C.2

1Department of Community Medicine and PHC Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching, Hospital/Nnamdi Azikiwe University, (NAU/NAUTH) Nnewi, Nigeria

2Faculty of Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adogu P. O. U., Department of Community Medicine and PHC Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching, Hospital/Nnamdi Azikiwe University, (NAU/NAUTH) Nnewi, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Background: Over the past centuries, mortality and morbidity patterns have been changing all over the world albeit with variations in timing and pace. These changes have been referred to as the epidemiologic transition. The main features of the transition include a decline in mortality, an increase in life expectancy, and a shift in the leading causes of morbidity and mortality from infectious and parasitic diseases to non-communicable, chronic, degenerative diseases. The transition is linked to improvements and advances in nutrition, hygiene and sanitation, and medical knowledge and technology. As such, the epidemiologic transition is related to the demographic transition and the nutritional transition, and is part of a more broadly defined health transition. Objectives: This paper was aimed at studying these shifts in pattern of mortality, life expectancy, and causes of death. Methods: Relevant literature was reviewed from medical journals, library research, Pub Med search, Google search and search using other internet search engines. The key words for the search were “Epidemiologic transition”, “Developing countries”, “Diseases” and “health related events”. Result: Several studies have given perspectives on epidemiologic transition, the factors that are responsible for the transition, the effects on the health of man, the scenarios in developed world and in the developing countries. Also highlighted are the challenges posed to humanity and possible measures to arrest the situation. Conclusions: It is obvious that epidemiologic transition is a reality that is present with humanity. In the developing world we have more problems on our hand as we have not succeeded in controlling the communicable diseases and the non-communicable diseases mostly nutrition-related are becoming predominant. This calls for action to prevent the dire consequences of double burden of disease arising from inaction.

Keywords:

Epidemiologic transition, Developing countries, Diseases, Health related events

Cite this paper: Adogu P. O. U., Ubajaka C. F., Emelumadu O. F., Alutu C. O. C., Epidemiologic Transition of Diseases and Health-Related Events in Developing Countries: A Review, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 150-157. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150504.02.

1. Introduction

Whereas common infectious and parasitic diseases such as malaria and the HIV/AIDS pandemic remain major unresolved health problems in many developing countries, emerging non-communicable diseases relating to diet and lifestyle have been increasing over the last two decades, thus creating a double burden of disease and impacting negatively on already over-stretched health services in these countries. Prevalence rates for type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVDs (cardiovascular diseases) in sub-Saharan Africa have seen a 10-fold increase in the last 20 years [1]. In the Arab Gulf current prevalence rates are between 25% and 35% for the adult population, whilst evidence of the metabolic syndrome is emerging in children and adolescents [1]. Thus, as acute infectious diseases are reduced, chronic degenerative diseases increase in prominence, causing a gradual shift in the age pattern of mortality from younger to older ages. It is believed that the epidemiologic transition in industrialized countries emerged towards the early 1900s, with rising levels of non-communicable diseases (NCD) that probably peaked by the mid 1950s, accompanied by a marked fall in infectious-disease morbidity and mortality [2]. Evidence for the emergence of the epidemiologic transition has often been associated with epidemics of diseases of the heart and blood vessels (including hypertension, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease), cancers, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, neuropsychiatric disorders and other chronic diseases [3], which are now major contributors to the burden of disease in both developed and developing countries. A developing country, also called a lower developed country, is a nation with an underdeveloped industrial base, and low Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries [4]. The objective of this review is to study these shifts in pattern of mortality, life expectancy, and causes of death in developing countries.

2. Methods

Relevant literature was reviewed from medical journals, library research and other internet search engines such as Pub Med search, Google search, Ageline, AGRIS (Agricultural database), CHBD (Circumpolar Health Bibliographic Database), Global Health, HubMed, POPLINE and SSRN (Social Science Research Network). In all these, the key words used were “Epidemiologic transition”, “developing countries”, “Diseases” and “health related events”.

3. Limitation of Study

The authors did not do a systematic review.

4. Results / Discussion

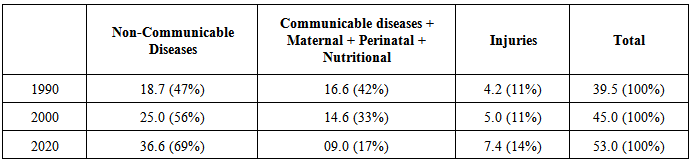

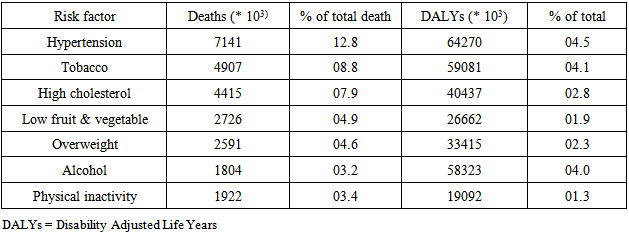

For a while, these diseases were associated with economic development and so called diseases of the rich. Then, by the dawn of the third millennium, NCDs appeared sweeping the entire globe, with an increasing trend in developing countries (Table 1) where, the transition imposes more constraints to deal with the double burden of infective and non-infective diseases in a poor environment characterized by ill-health system.Table 1. Evolution of NCD in Developing Countries (in millions) [5-7]

|

| |

|

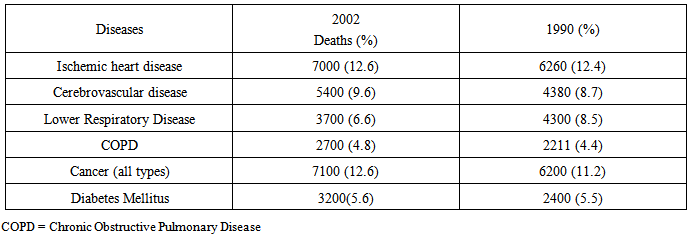

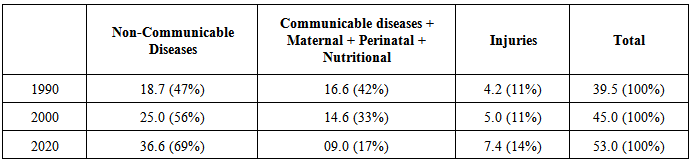

In 1990, the leading causes of disease burden were pneumonia, diarrhoeal diseases and perinatal conditions. By 2020, it is predicted NCDs will account for 80 percent of the global burden of disease, causing seven (7) out of ten (10) deaths in developing countries, compared with less than half today [5, 8].According the World Health Organization's statistics, chronic NCDs such CVDs, diabetes, cancers, obesity and respiratory diseases, account for about 60% of the 56.5 million deaths each year and almost half of the global burden of disease. In 1990, 47% of all mortality related to NCDs was in developing countries, as was 85% of the global burden of disease and 86% of the DALYs (disability adjusted life years) attributable to CVDs. An increasing burden will be born mostly by these countries in the next two decades. The socio-economic transition and the ageing trend of population in developing countries will induce further demands and exacerbate the burden of NCDs in these countries. If the present trend is maintained, it is predicted that, by 2020, NCDs will account for about 70 percent of the global burden of disease, causing seven out of every 10 deaths in developing countries, compared with less than half today. In 1990, approximately 1.3 billion DALYs were lost as a result of new cases of disease and injury, with the major part in developing countries. In 2002, these countries supported 80% of the global YLDs (years lost to diseases) due to the double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Consequently, their people are not only facing higher risk of premature life (lower life expectancy) but also living a larger part of their life in poor health [5]. These remarks indicate that NCDs are exacerbating health inequities existing between developed and developing countries and also making the gap more profound between rich and poor within low and middle-income countries.Table 2. Deaths caused worldwide by specific diseases (in millions) [5, 6]

|

| |

|

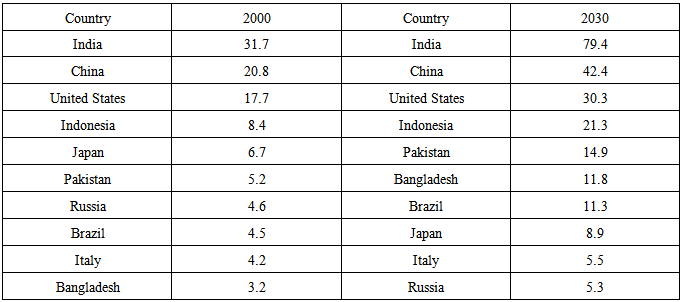

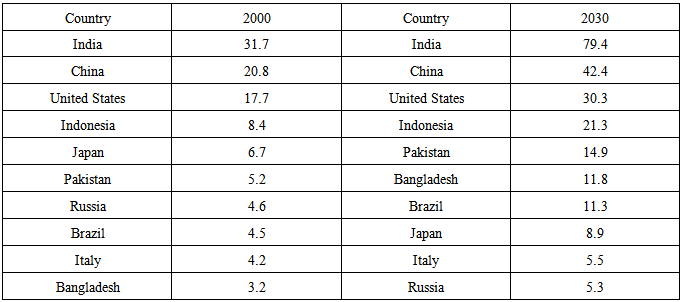

Table 3. Diabetes Prevalence (in millions) [9]

|

| |

|

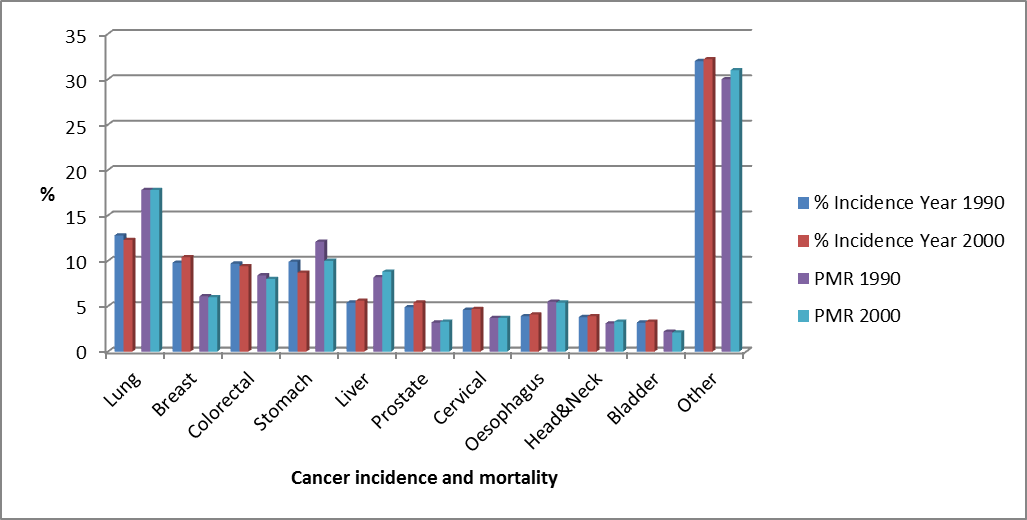

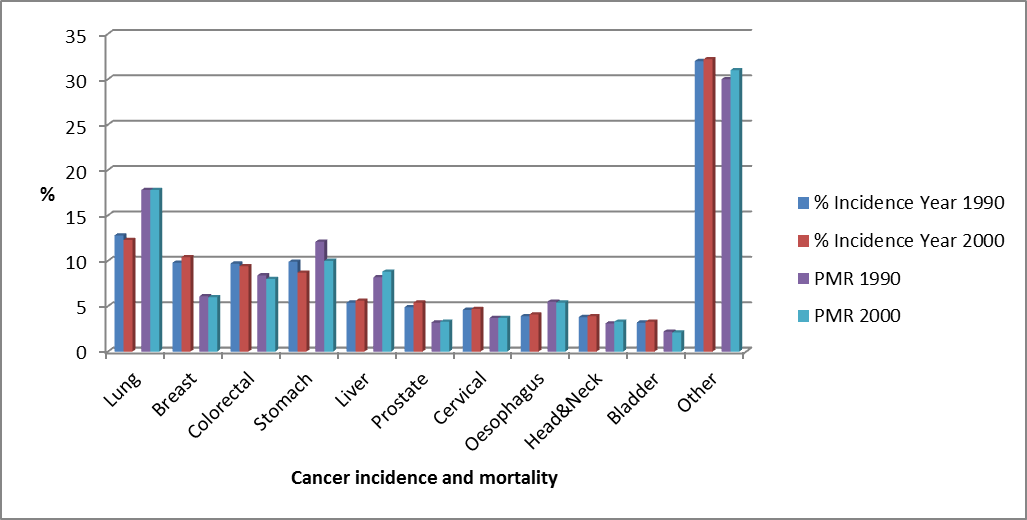

| Figure 1. Global cancer incidence and Proportional mortality rate 2000 and 1990 [10, 11] |

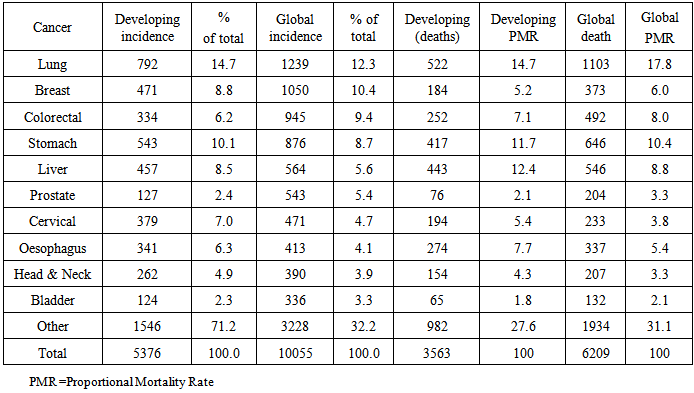

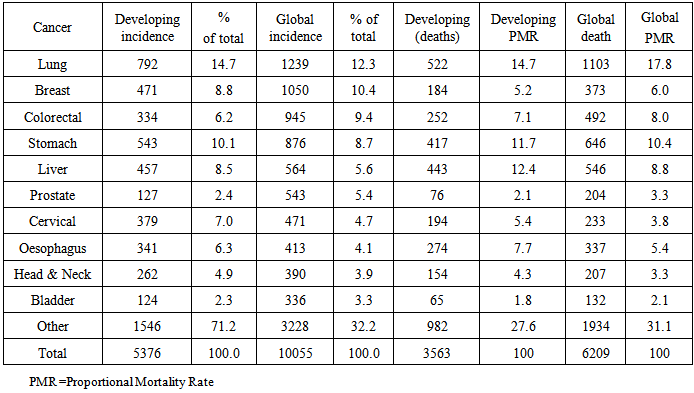

Table 4. Cancers: developing countries versus global incidence and death (in millions) in 2000 [10]

|

| |

|

Epidemiologic transition cannot be fully discussed without mentioning the other two well-known transitions in public health. They are “Demographic transition” and “Nutrition transition”. Demographic transition is the shift from a pattern of high fertility and high mortality to low fertility and low mortality [12]. | Figure 2. Population-Age Pyramids of the Developed and Developed Worlds |

| Figure 3. |

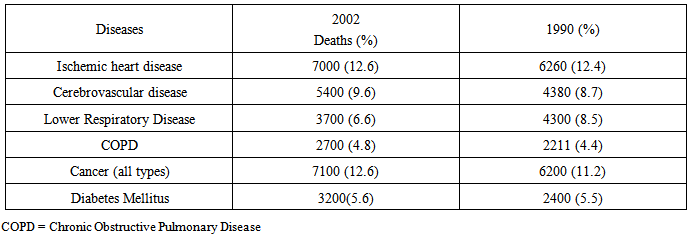

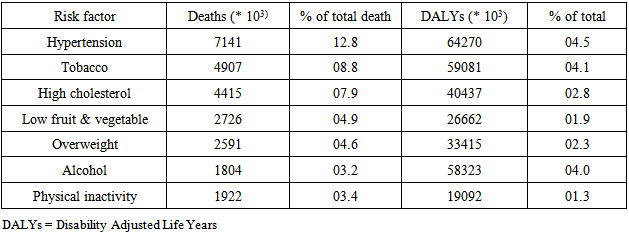

Demographic changes and the epidemiological transition are closely related. As discussed earlier, mortality levels start to decline at the beginning of the demographic transition. This is mainly caused by the reduction in mortality from infectious diseases and maternal and childhood conditions. As the health transition progresses, fertility levels and the burden of communicable diseases decline, and the average age of the population increases. Thus, eventually, there are more elderly people in the population, and they are more susceptible to non-communicable diseases than younger people. The increase in the number of susceptible individuals at older ages increases the overall incidence and prevalence of non-communicable diseases, thereby accelerating the epidemiologic transition. The developing countries are undergoing this transition but at a slower pace. There is improvement in child survival, increase in life expectancy at birth and decreasing fertility in developing countries [13].On the other hand, nutritional transition is malnutrition resulting not merely from the need for food, but the need for high quality nourishment [14]. Nutrition transition is also described as a shift from lack of food, to a rising problem of overabundance and obesity [15]. The term nutrition transition has been used to characterize the shift in disease patterns towards diet- or nutrition-related non-communicable disease including type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke, high blood pressure, gout and certain cancers. This shift in disease patterns is associated with changes in behaviours, lifestyles, diets, physical inactivity, smoking and alcohol consumption. The stages of the nutritional transition include: [12] The Hunter-Gatherers (Palaeolithic man) stage, Monoculture period, Industrialization/Receding famine stage, Nutrition-related Non-communicable diseases stage and Behavioural change stage.Stages of Epidemiologic TransitionEpidemiologic transition has been described to occur in 3 stages by Omran in 1971, [16] though Rogers and Hackenberg in 1987, [17] felt that the original theory lacked reference to violent and accidental deaths and death due to behavioural causes. They therefore proposed a fourth stage that they called the hybristic stage. The stages include:• The first or pre-transitional stage: the age of pestilence and famine• The second stage: the age of receding pandemics.• The third stage: the age of degenerative and man-made diseases.• The fourth stage: the hybristic stage.The age of pestilence and famine, is characterized by fluctuating mortality in response to epidemics, famines, and war. Crude Death Rate (CDR) is high and ranges from 30 to 50 deaths per 1,000 population. Life expectancy at birth is low, between 20 and 40 years, and the leading causes of death are infectious and parasitic disease, such as influenza, diarrhoea, and tuberculosis.The age of receding pandemics, is a transitional phase. During this stage, mortality starts to decline. CDR reaches a level of less than 30 deaths per 1,000 population, and life expectancy at birth increase to about 55 years. Improved sanitation, hygiene, and nutrition, and later also advances in medicine and public health programmes, help control epidemics and pandemics of infectious and parasitic diseases. As a result, an increasing number of people no longer die from infections at young ages but from chronic degenerative diseases at middle and older ages. The age of degenerative and man-made diseases, mortality continues to decline until it stabilizes at a level of less than 20 deaths per 1,000 population. In addition, life expectancy at birth increases and exceeds 70 years by the end of the third stage. The major causes of death are the so called chronic degenerative and man-made diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes. The term ‘man-made’ disease, hereby, include diseases related to radiation, accidents, food additives, occupational hazards, and environmental pollution.The hybristic stage reflects a change in the underlying causes of mortality and morbidity. The term ‘hybris’ refers to excessive self-confidence or a belief of invincibility. During the hybristic stage, morbidity and mortality are affected by man-made diseases, individual behaviours, and potentially destructive lifestyles. Individual behaviour such as physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, excessive drinking, and cigarette smoking increase the risk of adverse health outcomes, including heart disease, diabetes, cirrhosis of the liver, and lung cancer. Rogers and Hackenberg further remarked that while most environmentally-based infectious diseases are eradicated during the hybristic stage, some infectious diseases are increasing in importance due to individual lifestyle and man-made causes. A well-known example of such an infectious disease is HIV/ AIDS.A more widely acknowledged and adopted fourth stage of the epidemiological transition is the age of delayed degenerative diseases as proposed by Olshanky and Ault [18]. After mortality rates for males had stabilized during the 1950s and 1960s as a result of ‘epidemics’ of cardiovascular disease, male mortality again began to decline from around 1970 onwards. Olshanky and Ault considered this decline as a new stage in the epidemiologic transition. The age of delayed degenerative disease is characterized by “rapid mortality declines in advanced ages that are caused by a postponement of the ages at which degenerative diseases tend to kill” [18]. The postponement of deaths from degenerative diseases is a result of additional public health measures and advances in medical technology. Life expectancy at birth is expected to reach over 80 years by the end this stage.Models of Epidemiologic TransitionCountries and regions have shown differences in passing through the above-mentioned stages, with regard to timing, pace, and underlying mechanisms. Therefore, Omran [16] proposed several basic models of the epidemiologic transition. Initially he proposed three models, but later added a fourth variant.• The classical or western model• The accelerated variant of the classical model• The delayed model• The transitional variant of the delayed model.The classical or western model describes the gradual transition experienced by western societies. According to Omran, this transition started in the 19th century and was accompanied by a process of modernisation and industrial and social change.The accelerated variant of the classical model describes the transition observed in Japan and Eastern Europe. In these countries, mortality decline started later but reached the low level in a shorter period of time. The changes were based on general social improvements (for example in nutrition) as well as sanitary and medical advances.The delayed model depicts the transition as it occurs in developing countries. Mortality drop in these countries have mainly been achieved through the application of modern medical technology. Though initially mortality decline was fast, it slowed down after 1960s, especially in terms of infant and child mortality.The transitional variant of the delayed model typifies the transition in a number of developing countries such as Singapore, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, and Jamaica. In these countries, the rapid decline in mortality in the 1940s was comparable to that in countries matching the delayed model. However, the decline did not slacken to the same extentDeterminants of Epidemiologic TransitionThere are several factors involved in the epidemiologic transition. The most important are considered below.Demographic changes: These are composite of changes in both mortality and fertility. As populations become healthier, a reduction in mortality, particularly of infants and children, usually occurs, followed later by a fall in fertility rates. Therefore, more people will survive to adulthood and will have the disease patterns of adults, with non-communicable diseases at the top of list. They will also be exposed to diseases that more frequently affect elderly people, such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Thus, even with constant age-specific incidence rates of non-communicable diseases, the absolute number of cases and deaths from these diseases increases substantially with the above-mentioned demographic change. As life expectancy increases, the number of old people will increase. This will lead to changes in disease patterns and problems characteristic of the elderly and eventually the total number of deaths will increase as a result of the new age structure.Risk factors: Considering the factors affecting the emergence of non-communicable diseases, they do have a common denominator which is the risk factors. Indeed, tobacco, alcohol, high blood pressure, diet and physical inactivity were indicated, at different levels, as risk factors in the development of NCDs. Moreover, these risk factors are seen to affect people worldwide with an increasing tendency. (Table 5)Table 5. Burden of diseases and risk factors worldwide: year 20004 [19]

|

| |

|

Globally, many of the risk factors for heart disease, diabetes, cancer and pulmonary diseases are due to lifestyle and can be prevented. Physical inactivity, western diet and smoking are prominent causes [20]. Tobacco is the enemy number one. It is the most important established cause of cancer but also responsible in CVDs and chronic respiratory diseases. Tobacco and diet are the principal risk factors, responsible for more than 40% of cancer deaths and incidence. Obesity and dietary habits are the principal risk factors for diabetes mellitus type 2.Tobacco: In the 20 the century, approximately 100 million people died worldwide from tobacco-associated diseases such as cancers, chronic lung disease, diabetes and CVDs [5, 8, 21]. While tobacco consumption is falling in most developed countries, it is increasing in developing countries by about 3.4% per annum. Today, 80% of the 1.2 billion smokers in the world live in poorer countries where smoking prevalence among men is nearly 50% (48%) and 50% of the 5million deaths attributed to smoking in 2000 occurred in developing countries, also responsible for the increase in deaths by more than one million during the last decade. Tobacco remains the most important avoidable risk for the four classes of NCDs. It increases the risk of dying from coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease 2–3 fold. It increases the risk of many types of cancer, for lung cancer the risk is increased by 20-30fold. According to studies conducted in Europe, Japan and North America, 83–90% of lung cancers in men and 57–80 in women, are imputable to tobacco. Between 80 and 90 % of oesophagus, larynx and oral cavity are caused by tobacco and alcohol [22]. In developing countries, an estimated one-third of all cancer deaths was attributable to smoking in 1995. Finally, tobacco exacerbates the conditions of people living with COPD and asthma. Lifestyle: About 80% of cases of coronary heart disease, and 90% of cases of types 2 diabetes, could potentially be avoided through changing lifestyle factors [8, 23-25]. One-third of cancers could be avoided by eating healthily, maintaining normal weight, and exercising throughout life. It was estimated that in high-risk populations, an optimum fish consumption of 40–60 grams per day would lead to approximately a 50% reduction in death from coronary heart disease. A recent study based on data from 36 countries, reported that fish consumption is associated with a reduced risk of death from all causes as well as CVD mortality. Unfortunately, the fish consumption is very low even in some countries known for their large fish stock like the north African region. Daily intake of fresh fruit and vegetables in adequate quantity (400–500 grams per day), is recommended to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and high blood pressure. But, once more, this is thwarted by the western lifestyle invading developing countries.Overweight/Obesity: Overweight and Obesity lead to adverse metabolic changes such as insulin resistance, increasing blood pressure and cholesterol [8, 26]. Consequently, they promote CVDs, diabetes and many types of cancer. Worldwide, overweight affects 1.2 billion of which 300 million are clinically obese. In some developed countries like USA, the prevalence reaches 60% but developing countries like Kuwait have also a very high prevalence. More and more children are suffering from overweight and obesity. However, the most contrasting phenomenon is to find Overweight/ Obesity and malnutrition side by side in low- and middle-income countries and hence contributing to the growing burden afflicting these countries. According to the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) and the WHO World Health report 2002, about 60% of diabetes globally can be attributable to overweight and obesity. In other respects, it is estimated that 60% of world's population do not do enough physical activity.Alcohol: Alcohol consumption has also increased in the last decades, with the major part of this increase imputable to developing countries. In 2000, Alcohol was responsible for nearly 2 million deaths in the world, representing 4% of the global disease burden. Moreover, alcohol was estimated to cause 20 to 30% of oesophagus cancer, liver disease, epilepsy, motor vehicle accidents and other hazards [8].Practices of modern medicine: Several changes have occurred in the quantity, distribution, organization and quality of health services that have contributed to the epidemiologic transition. The discoveries and technological developments of the twentieth century, such as the development of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents, insecticides, vaccines and diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, have resulted in remarkable progress in the prevention and control of many diseases and in the effective management of many others. One of the most dramatic victories has been the eradication of smallpox. Another evident success has been the reduction of morbidity and mortality from diseases for which there are available protective vaccines such as poliomyelitis, diphtheria, tetanus and measles. It must, however, be remembered that relaxation of vaccination efforts can very quickly result in the re-emergence of these diseases as happened with poliomyelitis in Pakistan and is now the case with diphtheria in Russia and Ukraine [19].Although therapeutic interventions have been the key element in saving millions of lives each year and in reducing some of the serious complications that often follow infection, they actually do not modify the probability of becoming ill (except in so far as early treatment reduces the risk of spread of infection to others). In chronic diseases, this type of intervention actually produces the paradoxical effect of increasing the absolute morbidity level.On the other hand, the cure-oriented intervention techniques of modern medicine that permit the liberal use of antimicrobials and chemotherapeutic agents and an increasing number of manipulative procedures have been responsible for some side effects of diseases. In addition to side effects such as allergy, depression of bone marrow activity and deafness, excessive use of antibiotics may cause what are described as superimposed infections. The excessive use of antimicrobials inhibits indigenous organisms that compete with external invaders and permits colonization and proliferation of organisms that are non-pathogenic under normal conditions.Infections associated with manipulative techniques are another example, particularly under conditions where aseptic techniques are not strictly followed. The most evident of these is neonatal tetanus, which occurs through contamination of the umbilical stump. The spread of viral hepatitis B and C and HIV infection through the use of contaminated needles and through unscreened blood transfusions is another example in which intervention becomes a source of infectious disease. In addition, the use of equipment such as urethral catheters and endotracheal tubes permits organisms to gain access to otherwise healthy sterile organs.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The changing pattern of diseases observed over recent years, from acute infectious and deficiency diseases to the chronic non-communicable diseases, is a continuous process of transformation with some diseases disappearing and others appearing or reappearing.It is clear that infectious diseases are still an important public health problem and a major cause of death and of illness and will continue to be so for future generations. At the same time, non-communicable diseases are coming to the forefront as causes of illness and death, especially in countries where it used to be possible to control many communicable diseases.This transition is very vulnerable as many biological, environmental, social, cultural and behavioural factors have been responsible for structuring these patterns in the community. It is subject to breaks in continuity, slowdowns or even reversals of the transition.Several stages of transition may overlap in the same country. This represents a challenge to national health authorities, which must continuously modify their health care services to address the needs created by this changing pattern of diseases. Epidemiologic surveillance has a major role to play in identifying the chances and in planning how to address them and should be given the attention it deserves. Also, health authorities have an important duty to try and shape the transition in a positive way by all possible means.The public has a major role to play, and hence the necessity for public health education and promotion of healthy lifestyles. Health education efforts to achieve positive behavioural changes are essential for the prevention and control of diseases. A carefully conceived media campaign can have a beneficial effect on changing behaviours related to the occurrence of diseases, such as smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption and other dangerous behaviour and lifestyles.

References

| [1] | Amuna P, Zotor FB. Epidemiologic and Nutritional Transition in developing countries: impact on human health and development. Proceedings of The Nutrition Society. 2008 February;67(1):82-90. |

| [2] | Detels R, Breslow L (1997) current scope and concerns in public health. In Oxford Textbook Public Health,vol.1, 3rd ed., pp3-17[R Detels, WW Holland, J McEwen and GS Omenn, editors]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [3] | Patel MS, Srinivasan M, Laycock SG (2004) Nutrient-induced maternal hyperinsulinemia and metabolic programming in pregnancy. In the impact of maternal nutrition on the off springs. Vol. 55, Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series Paediatric Program, pp. 137-157[G Hornstra, R Uauy and X Yang, editors]. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd. |

| [4] | Sullivan A, Steven M S. Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. 2003; p. 471. ISBN 0-13-063085-3 |

| [5] | The World Health Report: Today’s challenges. [http://www.who.int/whr/2003/en]. Geneva, World Health Organization. |

| [6] | Burden of Disease Unit: The global burden of disease in 1990. [http://www.hsph.havard.edu/organizations/bdu/GBDseries.htm]. Havard University Press. |

| [7] | Hutubessy R, Chisholm D, Edejer TT: Generalized cost-effectiveness analysis for national-level priority setting in health sector. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2003, 1:8. |

| [8] | World Health Organization: Diet, Nutrition and the prevention of Chronic Diseases. In Technical report Series 916 Geneva, World Health Organization:2003. |

| [9] | International Diabetes Federation (IDF): Action Now: A joint initiative WHO and IDF.[http://www.idf.org]. |

| [10] | GLOBOCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. 2000 [http://www-dep.iarc.fr/globocan/globocan.html]. |

| [11] | Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J: Global Cancer Statistics. CA CANCER J CLIN 1999; 49:33-64. |

| [12] | What is Nutrition Transition? http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/nutrns/whatis.(Accessed on 30 November 2012). |

| [13] | Omran AR. The Epidemiological Transition: a theory of the Epidemiology of population change. The Milbank Quarterly,2005;83(4):731-757. |

| [14] | Wikipedia. Nutrition Transition. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/nutrition transition(Accessed on 30 November 2012) |

| [15] | Alanna O. Cultural Culinary Wisdom: Combating the nutrition transition. Global studies student papers. http://digitalcommons.province.Edu/glbstudy students/15 (Accessed on 30 November 2012). |

| [16] | Omran AR (1971). The Epidemiologic Transition: a theory of epidemiology of population change. Milbank Q49:509-538. |

| [17] | Rogers R G, Hackenberg R. Extending Epidemiologic Transition Theory, Social Biology, 1987;34:234-243. |

| [18] | Olshanky J, Ault B. The Fourth Stage of the Epidemiologic Transition: the age of delayed degenerative diseases. The Milbank Quarterly, 1986; 64 (3):355-391. |

| [19] | Mechanisms of Epidemiologic Transition. http//www.cba.edu.kw/eqbal/epidemiological/transition.htm(Accessed on 30 November 2012). |

| [20] | Alberti G: Non-communicable disease: tomorrows pandemic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001;79:906-1004. |

| [21] | This month’s special theme: Tobacco. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2000; 78:866-948. |

| [22] | Le code Europeen contre le cancer [http://telescan.nki.nl/code/fr code.html]. |

| [23] | Stampfer MJ: Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl j Med 2000; 343:16-22. |

| [24] | Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group: Reduction in the incidence of type 11 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl j Med 2002; 346:343-403. |

| [25] | Key TJ: The effects of diet on risk of cancer. Lancet 2002; 360:861-868. |

| [26] | Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, Wilson PM, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Vasan RS: Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl j Med 2002; 347:305-313. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML