-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2015; 5(3): 130-134

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20150503.04

Risk Factors of Mortality among Children Admitted with Severe Pneumonia at a Reference Hospital in Khartoum, Sudan

Karimeldin Mohamed Ali Salih 1, Jalal AliBilal 2, Amani Hussein Karsani 2

1College of Medicine, University of Bahri, Khartoum North, Sudan; College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, KSA

2College of Medicine, Qassim University, Buraydah, KSA

Correspondence to: Karimeldin Mohamed Ali Salih , College of Medicine, University of Bahri, Khartoum North, Sudan; College of Medicine, King Khalid University, Abha, KSA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction: Pneumonia is the leading cause of mortality among under-five children. Previous studies have documented factors of mortality. These factors were not addressed in this country. This study aimed to determine risk factors of death among children hospitalized for severe pneumonia. Methodology: This cross-sectional hospital-based study was conducted in Khartoum Children Emergency Hospital among children with severe pneumonia aged 2-59 months from August 2010 to April 2012. Management outcome (died/survived) were recorded within 5 days. History and physical examination were recorded, chest radiograph and a sample of 5 ml of venous blood was collected for white blood cells count, hemoglobin level and serum level of albumin, urea, creatinine and C-reactive protein. Blood samples were cultured in appropriate media. Data were analysed using SPSS software for windows version 16.0. Results: Of the195 recruited children, 33 died (16.9% case fatality). Children who died were younger compared to survivals (n=162) (p<0.001). Malnutrition, dehydration and chest in drawing were frequent among dead compared to survivals; p<0.001, p=0.033 and p=0.017, respectively. The dead had lower mean hemoglobin (p=0.010) and lower mean serum albumin level (p<0.001) and significantly high mean C-reactive protein concentration (p<0.001) and high blood urea (p<0.001). Independent risk factors of mortality were: young age (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.02-1.12), chest in drawing (OR 8.63; 95% CI 2.08-35.83) and history of bronchial asthma (OR 10.31; 95% CI 2.25-47.22), a low concentration of C-reactive protein (OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.37-0.66) and increased hemoglobin concentration (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.32-0.49). Conclusions: improvement of management policies and settings of severe pneumonia to decrease mortality. In addition, primary prevention, health education programs and strategies to combat co morbidities. Addressing the risk factors of increased mortality of children with severe pneumonia. These are young age, history of bronchial asthma, high C-reactive protein and anemia.

Keywords: Pneumonia, Hypoalbuminemia, Anemia, Diarrhea, C-reactive protein, Chest in drawing

Cite this paper: Karimeldin Mohamed Ali Salih , Jalal AliBilal , Amani Hussein Karsani , Risk Factors of Mortality among Children Admitted with Severe Pneumonia at a Reference Hospital in Khartoum, Sudan, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 3, 2015, pp. 130-134. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150503.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pneumonia is a wide spread infection with an incidence of30% and 39%among children in Africa and Southeast Asia respectively [1]. The worldwide estimate was120 million episodes of childhood pneumonia and 1.3 million deaths, the bulk of which (81%) was in children under the age of 2 years [1]. Despite the global decline in under-five mortality rate, dropping from 90 to 46 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2013, pneumonia is still the leading cause of mortality among this age group [2]. Mortality issues identification to label children at risk of death from pneumonia on admission and during hospital stay is of paramount importance. Previous studies have documented sets of factors that may indicate an unwanted outcome of pneumonia [3, 4]. An Indian study identified head nodding at admission, abnormal leukocyte counts, cyanosis, pallor and altered sensorium as factors associated with mortality [3]. Furthermore, Demers et al reported indrawing of the chest, hepatomegaly, young age, grunting, alteration of general condition and malnutrition as mortality factors associated with severe pneumonia in children from Bangui, Central African Republic [4].Further studies in low-resources countries are essential to determine mortality factors of pneumonia in young children. The findings may help employment of the scant resources for the development of appropriate strategies for prevention. These factors were not addressed before in this country.This study was conducted to determine risk factors of death among Sudanese children hospitalized for respiratory symptoms satisfying the WHO clinical criteria of severe pneumonia.

2. Materials and Methods

- Study designThis cross-sectional hospital-based study was conducted in Khartoum Children Emergency Hospital (KCEH) in the period from August 2010 to April 2012. KCEH is the major children referral as well as primary care hospital. It has a capacity of 240 beds serving more than five million people, the population of the capital, Khartoum [5].Sample collectionsCases enrolled are those who report to the ER of KCEH because they have severe pneumonia. Cases sorted as severe pneumonia out of all cases presented to the ER, Inclusion and exclusion criterionsChildren who satisfied the inclusion criteria namely age 2-59 months and had respiratory system findings fulfilling the WHO definition of clinically severe pneumonia were enrolled in this study. Severe pneumonias defined by the WHO as having cough or difficult breathing plus at least either central cyanosis/oxygen saturation <90%, severe respiratory distress and signs of pneumonia with a general danger sign [6]. Critically ill children on admission were excluded as well as children who are known to have tuberculosis, possibility of HIV or other chronic conditions complicated by pneumonia. Children whose parents/ guardians refused to be enrolled in the study were excluded as well.

3. Methodology

- After admission parents/guardian had signed an informed consent and children were managed by the hospital medical staff according to the WHO guidelines of management of severe pneumonia and the outcome variables (died/survived) were recorded within 5 days of admission [6]. At admission, relevant history was noted and physical examination findings were recorded for every child in addition to anthropometric measurements. Fever was defined as an axillary temperature of ≥37.5°C. Antibiotic treatment was noted within the last 5 days prior to hospital report. Malnutrition was defined as weight for age < −2 Z score. Anterior-posterior chest radiography was taken in erect position from every child and independently interpreted by a radiologist. The chest radiograph was interpreted as either abnormal, if it showed pleural effusion, consolidation and/or infiltrate, or otherwise normal if none of the previous radiological findings was detected [7]. A sample of 5 ml of venous blood was collected for white blood cells count, hemoglobin level and serum level of albumin, urea, creatinine and C-reactive protein. In addition all blood samples were cultured in appropriate media and recorded as positive or negative based on whether there was colony growth.For the purpose of this study two outcomes were defined as survived versus died in the hospital in a period of 5 days standard WHO treatment of severe pneumonia [6]. Data were collected using a flow data sheet.Data were entered into SPSS software for windows version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A. 2007). Variables were analyzed and summarized in frequency tables. Means (SD), medians and modes where necessary, were calculated for numerical variables. Dichotomous variables were compared by the Χ2 test as well as Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. The Student t-test was used to compare means of normally distributed numerical variables and Mann-Whitney test was used for skewed data. Variables that were associated with death by univariate analysis at a significance level of p<0.10 were included into a model of multivariate logistic regression. The significance of the association was set at p<0.05 while the strength of the association was determined by estimating the odds ratio (OR) within 95% confidence interval limit.Ethical clearanceThe hospital Development and Ethical Committee had approved this study.

4. Results

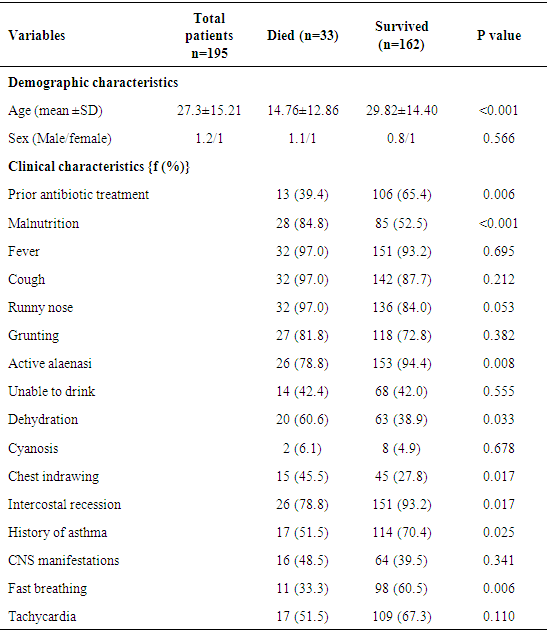

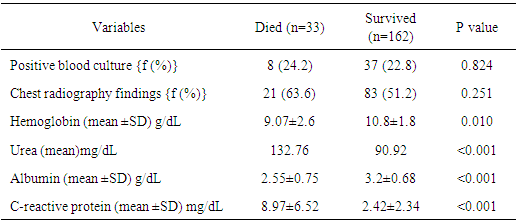

- The total number of children who were admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of severe pneumonia during the study period was 247. Fifty children were either discharged against medical advice or their guardians did not agree to be enrolled in the study. Two children were excluded because of inadequate data. The data of the remaining195 children were analyzed. They had a mean (SD) age of 27.3 (15.7) a mode of 24 and a range of 57months. Female/male ratio was 1.2/1 however; there was no gender difference among different ages (p=0.233). There were 33 deaths accounting for a case fatality rate of 16.9% among children admitted with severe pneumonia. The remaining (n=162) children were alive on in hospital treatment completing the 5 days period of the study.Children were classified into two groups those who died (n=33) and those who survived (n=162) during hospitalization for severe pneumonia.Children who died of severe pneumonia during hospitalization were younger (age < 18 months) compared to survivals (p<0.001) however, there was no significant difference in sex distribution (p=0.566). Malnutrition, dehydration and chest indrawing were significantly frequent among those who died compared to those who survived severe pneumonia; p<0.001, p=0.033, p=0.017, respectively. On the other hand, prior antibiotic treatment, active alaenasi, intercostals recession, history of asthma and fast breathing were frequently seen among survivals compared to those who died p=0.006, p=0.008, p=0.017, p=0.025 and p=0.006, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the frequency distribution of fever, cough, runny nose, grunting, inability to drink, cyanosis, central nervous system (CNS) manifestations and tachycardia (p>0.05) as table 1 illustrates.

|

|

|

5. Discussion

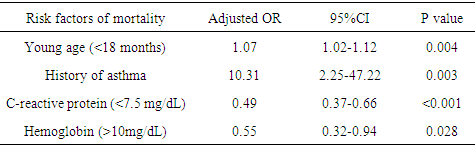

- The magnitude of the major health problems in children in Sudan was not recently studied except for two reports on adherence on guidelines of childhood pneumonia treatment protocol and pneumonia characteristics in children below five years of age [8, 9]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on risk factors of mortality among children hospitalized with WHO-defined severe pneumonia in Sudan.The case fatality rate of severe pneumonia among 2-59 month old hospitalized children was approximately 17% in this study. This rate is higher than comparable settings but consistent with Indian reports [10-14]. Different definitions of variables and classifications of pneumonia and the period of follow-up may attribute to the different figures of mortality conveyed in these studies [9, 10]. Moreover, seasonality of pneumonia mortality was documented in which lower respiratory tract infections, as in this study period, coincided with incidence pattern [15]. However comorbid factors, which were not otherwise excluded in this study, might have confounded for this high rate of fatality. Standardized management of severe pneumonia in children and clear operational definitions might help improve comparison. Mortality associated with severity and young age is consistent with other studies [11]. The common features among these settings are the poor hospital facilities. Similar to other studies, the co morbid condition smalnutrition, dehydration and the clinical sign chest indrawing were significantly frequent among those who died compared to those who survived [14, 16, 17]. Moreover, death was associated with low hemoglobin and serum albumin concentration, and high C-reactive protein. Low serumalbumin and hemoglobin concentrations and high CRP value were reported in previous studies to be associated with reduced survival of patients with community-acquired pneumonia [18, 19].Documentation of risk factors of mortality due to pneumonia at admission or during the clinical course is helpful to foresee and monitor approaches to reduce mortality during hospitalization [13]. In this study young age, chest in drawing, history of bronchial asthma, hemoglobin concentration<10g/dL and a C-reactive protein >9mg/dL were adverse risk factors of mortality. A child younger than 18 month, in this report, had 7% chance of mortality due to severe pneumonia than an older one. Several studies, however with varied definitions, had documented young age as an independent risk factor of mortality in children with pneumonia [10, 13, 14, 17, 20]. These young children, as reported by Ramachandran et al., were mostly malnourished and had low hemoglobin concentration [14].The immune system of the young may be weakened by malnutrition particularly in infants who are not exclusively breastfed. This necessitates a rational for meticulous care of young children upon admission.This study validates chest in drawing as the single useful clinical predictor of mortality in children with pneumonia as it increased the odds of dying by more than 8 times. This finding is in accordance with WHO definition of severe pneumonia [6]. Nevertheless, chest in drawing is a subjective clinical sign with variable interpretation among different health workers. Wandeler et al., haddocumented chest in drawing as a significant predictor of hypoxemia in similar age children with pneumonia (adjusted DOR 9·8, 95% CI 1·5–65) hence death is most likely among hypoxemic children. However, Ramakrishna et al had refuted any relation between mortality and chest in drawing [21].Chest in drawing alone, in one setting, was found to have has a high positive predictive value but indefinite negative prediction although when combined with other clinical variables such as age or weight for age, its value as a risk of mortality was much increased [22]Children, who history of bronchial asthma in this study had had significantly increased odds of dying than that without. Nascimento-Carvalho ET al., reported a comparable result from Brazil [17]. However, Jroundi et al results documented history of asthma as the only protective factor against negative outcome of pneumonia [23]. Though, absence of fever can differentiate asthma from pneumonia however, fever caused by viral infections are known to be triggers of asthma attacks [24]. The ambiguity of differentiation between asthma and pneumonia on the basis of the WHO criteria might label asthmatic children as pneumonia, a factor that may attribute to the difference in mortality reports [6].High serum concentration of C reactive protein and low hemoglobin concentration were reported as predictors of severe pneumonia and as risks of mortality in different setting as in this series [18, 20, 25]. However, conflicting results on C reactive protein as predictor of mortality were reported [26]. These disputes might have instigated from inconsistencies in the model characteristics of the enrolled patients among different studies. Similarly, the cut-off value of hemoglobin concentration at which mortality risk increases might vary with the causes of anemia and pneumoniain the population [20].This study has limitations. First the sample was collected from a single facility and hence the results are difficult to be generalized as they may underestimate the real burden of pneumonia. Second, many other demographic and clinical variables that may yield better results were not included. Finally, the follow-up period was limited to the first 5 days of admission however, extension might change the outcome.

6. Conclusions

- In conclusion, pneumonia case fatality rate is high necessitating improvement of management policies and settings. Augmentation of the primary prevention, health education programs and early management strategies to combat co morbidities such as malnutrition, anemia and dehydration. Apt management of children with hypoalbuminemia, high C reactive protein and high urea level and specifically addressing the independent risk factors of increased mortality of severe pneumonia as young age, history of bronchial asthma, high C-reactive protein and anemia.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML