-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2015; 5(2): 82-86

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20150502.04

Cessation of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Cesarean Section Mothers: Need More Attention

Mahshid Ahmadi, Seyyed Mohammad Moosavi, Seyed Jaber Mousavi, Yekta Ghasemi

Department of Community Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

Correspondence to: Mahshid Ahmadi, Department of Community Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

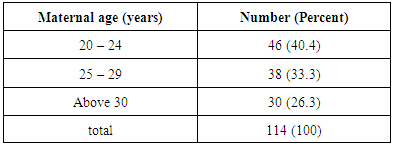

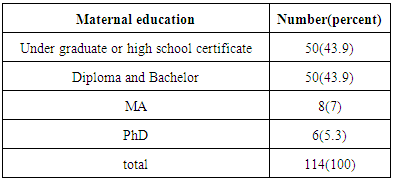

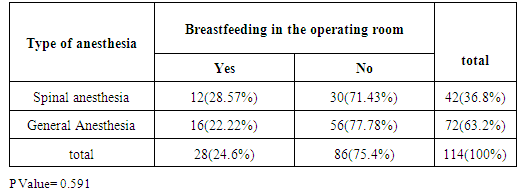

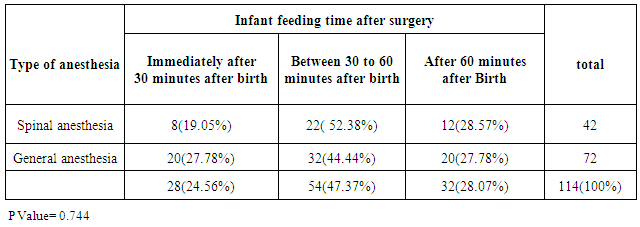

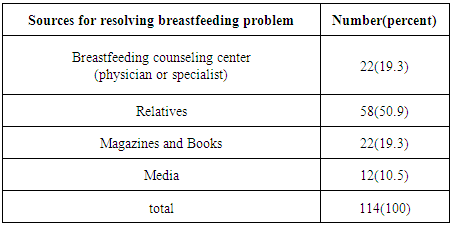

The global rate of caesarean section which can influence exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and finally children's health is rising progressively. Assessing the related factors can improve this issue. This study evaluated the factors influencing cessation of exclusive breastfeeding. In this cross-sectional study, data were obtained from 114 Cesarean mothers who had formula feeding referred to health centers (2013). Chi-square test and SPSS-19 were used for statistical analysis and P-value less than 0.05% was considered as significant. Of the 114 mothers participating in the study, 46 mothers (40.4%) were aged 20-24 years (26.29 ± 4.04); 43.9% were under-graduates or high school graduates; 71.9% were unemployed; 56.1% passed their first delivery, 68.4% had given birth in private hospitals, 63.2% underwent general anesthesia and 75.4% had no breastfeeding in the operating room, no statistically significant difference was noted in terms of breastfeeding in OR and type of anesthesia (P Value = 0.591). Breastfeeding in 30 minutes after delivery was observed in 24.56%, no statistically significant difference was noted in terms of time to start breastfeeding and type of anesthesia (P Value= 0.744). 75.4% didn’t experience skin to skin contact after delivery and for 57.9%, rooming-in policy was not implemented. For 50.9%, relatives were main source for resolving the nursing problems. No significant relationship was found between the type of anesthesia and breastfeeding in OR, as well as the time to feed the baby after birth. Implementing WHO ten steps, at all hospitals especially private ones, supporting young mothers with lower parity, medical consultation to address mothers’ nursing issues after delivery, improving the knowledge of the less educated & housewives are also important measures that should be considered.

Keywords: Exclusive Breastfeeding, Cesarean Section, Formula feeding

Cite this paper: Mahshid Ahmadi, Seyyed Mohammad Moosavi, Seyed Jaber Mousavi, Yekta Ghasemi, Cessation of Exclusive Breastfeeding in Cesarean Section Mothers: Need More Attention, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 82-86. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150502.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- During the last decades, the importance of good nutrition for growth and development of infants has been well established and is considered as a major public health issue. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life provides unique benefits for infants and mothers as well [1]. The Global Performance Monitoring based on the World Health Organization report on 2013 indicates that only 37% of infants worldwide and 28% of infants in Iran are fed exclusively with breast milk in the first 6 months of life [2]. Among factors contributing in failure of exclusive breastfeeding during first 6 months of life, cesarean section has been evaluated in several studies [3-13]. Cesarean section may influence exclusive breastfeeding in various ways; including anesthetic effects on mother and baby during first contact, mother's inability to get correct position for breastfeeding due to pain or having intravenous line and also impaired Bonding bonding between mother and) newborn due to negative feelings of mother to herself, baby, physician or relatives [2, 11-16]. On the other hand, feeding the infants with formula in mothers who undergone cesarean section is associated with decreased duration of breastfeeding and may lead to early weaning [17-19]. Since 40% of deliveries in Iran are performed by cesarean section 2), which is higher than global rate, and since the cesarean section negatively affects exclusive breastfeeding in first 6 months of life, yet few studies have been done in Iran about factors influencing natural process of breastfeeding in mothers who undergone cesarean section and the contributing factors still are not fully understood.In this study, we assessed the factors affecting cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in mothers who referred to Sari Health Centers in order to implement prophylactic measures and minimize risk factors so that children’s health to be improved and breastfeeding to be promoted.

2. Materials and Methods

- In this descriptive–analytical study, the respondents were selected from mothers who referred to Sari Health Centers for six months in 2013, seeking care for their children. The entire sample for the present study consist of 134 women, based on sample size formula and considering the previous researches in this field. So, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 114 mothers were recruited. The inclusion criteria were: 1- Mothers who gave birth by cesarean section delivery; 2-Gestational age of 38-40 weeks at time of delivery; 3- Healthy newborn (normal physical examination and discharge from hospital without the need for special care); 4- Infants under one year of age during study period; 5- Infants fed with formula or with combination of formula and breastfeeding since first month of age; 6- Sari as the birthplace of infants.The exclusion criteria were: 1- Introducing artificial formula because of maternal diseases (such as HIV infection, CMV, chicken pox, measles and tuberculosis) that are contraindications for breastfeeding; 2- Introducing artificial formula because of consumption of drugs (such as stimulants and narcotics, anti-neoplasm and radioactive agents) by mother that are contraindications for breastfeeding; 3- Mother breast problems that may interfere with successful breastfeeding (such as lack of breast development during pregnancy, breast hyperplasia, previous breast surgery, flat or inverted nipple); 4- Infant diseases (such as galactosemia and phenylketonuria ) that make breastfeeding impossible; 5- Starting formula after first month of age( because of eliminating factors which may be unrelated to cesarean delivery); 6- When mother cannot recall required data about her pregnancy.Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences granted study ethical approval. Women were informed about the benefits of the study and reassured about anonymity and confidentiality of their information and their right to withdraw from the study, then consent form was introduced to them. Each of the participants who voluntary decided to participate in the study signed the consent form and filled data recording forms. In this study researchers used questionnaire including mothers’ demographic information (age, occupation, level of education), parity, place of delivery, type of anesthesia, kangaroo mother care (KMC) at operating room, starting time of first breastfeeding, mother's need for analgesics, education for correct positioning of breastfeeding, breastfeeding after birth in hospital and its time period, assistance by nursing staff for breastfeeding, assistance by mother’s relatives in hospital, rooming-in policy, infant or maternal diseases, any special problems (including breast problems, insufficient milk and infant refusing to take breast after hospital discharge) and finally, mother’s source to resolve breastfeeding problems out of hospital, to validate the mother’s self-reported items hospital record checked too. The obtained data were statistically analyzed using SPSS-16 and Chi-Square test and P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

- In this study that was done to evaluate factors influencing natural process of breastfeeding after cesarean section, 114 mothers aged 26.29 ± 4.04 years were evaluated. Forty six (40.4%) mothers were in 20-24 years group or in young age period (as seen in table 1). Fifty (43.9%) mothers were Under graduate or had high school certificate and 50 (43.9%) had Diploma and Bachelor degree (as seen in table 2).

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- This study has evaluated the factors affecting the exclusive breast feeding in mothers who gave birth by cesarean section delivery. Based on the findings, 73.7% of mothers were aged less than 30 years and 56.1% of them were experiencing their first delivery, It seems more formula feeding percentage in lower age & parity partly relates to increasing knowledge and experience of mothers with increasing age, As this study showed that with increasing the level of literacy, formula feeding rate decreased (87.7% of mothers had less than a bachelor's degree). Begum et al [20], also Kornides and colleagues [21], found in their studies that increase in mother knowledge is associated with more trends to start and continue breast feeding. Furthermore, in this study 71.9% of mothers were housekeeper, and 28.1% were employed. Although the mother's employment factor is one of the factors affecting on breastfeeding [22], But it affects when mother returns to work [23], and it seems that working mothers have better attitudes and are more willing to breast-feed during maternity leave because of in service trainings and work environment limitations, and it is necessary to compare the two groups' attitudes and willingness about formula feeding in future studies. As Attanasio, et al in their study found that working mothers had higher education level and their employment had no effect on their breastfeeding in compare with housewives, rather increasing in working hours was associated with cessation of exclusive breast feeding [24]. So lower mother age and parity and employment raise more need to education and supporting these mothers which bring up the importance of WHO ten steps (Step 3 & 10) [1].In this study, 68.4% of deliveries were performed in private hospitals. According to the instructions provided by Ministry of Health and Medical Education, both public and private hospitals with obstetrics and gynecology wards must implement the WHO ten steps to achieve successful breastfeeding of infants so to be awarded the Baby-Friendly Hospital designation 1). Thus, being a public or private hospital should not impact on the prognosis of breastfeeding, but being Baby-Friendly Hospital, is more important. Rowe-Murray found that the Baby-Friendly Hospitals have better performance compared to other hospitals, especially in terms of shorter time to start breastfeeding after birth by cesarean section 25). In our study the mothers (1) did not know what is Baby-Friendly Hospital, (2) did not know their hospital was Baby-Friendly or not, (3) being Baby-Friendly Hospital has not been an important measure for them to choose the hospital for delivery, On the other hand, the number of deliveries in public hospitals is far more than private hospitals and in contrast, number of mothers who refer to private hospitals for cesarean section is higher than public hospitals [26]. Therefore, with regards to the above subjects, it is required to conduct a study to compare cesarean mothers who feed their infants with formula in both private and public hospitals and also private hospitals should be monitored continuously.In this study, 63.2% of mothers who started formula after cesarean section had been undergone general anesthesia. Infants delivered by cesarean section are sleepier than those have not received anesthesia. It may take several days for sleepiness to be disappeared and infants may temporarily have weak sucking reflex too. On the other hand, following general anesthesia, mother is still sleepy for a time which in turn, can affect the contact between mother and newborn. While in spinal anesthesia, mother can start breastfeeding immediately after delivery 1), that improves quality of breastfeeding [27, 28].step 4 of WHO ten steps emphasizes on early breastfeeding & skin to skin contact after delivery1), Delayed breastfeeding for the first time after birth is directly associated with failure of exclusive breastfeeding [13-15, 28], and skin to skin contact even without breast sucking improves the rate of successful breastfeeding [29], In our study, 75.4% of mothers didn’t fed their babies in the operating r oom (71.43% and 77.78% of mothers who had undergone cesarean section by spinal anesthesia and general anesthesia respectively), no significant relation was noted between type of anesthesia and earlier start of breastfeeding in operating room (P=0.591). Spear et al, showed similar results [30]. In Iran there is no exact data about implementation of this policy in operating room but based on the data of normal vaginal deliveries, Nahidi et al found that 90% of midwives in Iran do not implement skin contact between mother and newborn after birth [31]; so it seems the problem is implementation of this policy rather than type of anesthesia. Presence of mothers’ relatives in the operating room can improve this condition as Spear et al emphasized that30); while current policies in our country does not allow mother’s relatives to attend in delivery room or operating room.Educating breastfeeding techniques to mothers before and after cesarean section, affects breastfeeding process in several aspects [28, 32-33], and should be carried out based on steps 3 & 5 in WHO ten steps1). In our study, 43.9% of mothers had not received breastfeeding education. Two possibilities exist; f irst, the mothers might be multipara and experienced from their previous deliveries; or the education policy was not executed in these hospitals and remained to be more clarified in future studies.Rooming-in policy (WHO step 7) was performed just for 42.1% of our cases that is very important in successful breastfeeding 1), and hospital managers should revise their policies.In our study, 96.5% of newborns had no physical problem as a reason for formula feeding although mothers were not asked about reason for starting formula; which was among the limitations of our study, and based on the data 17.5% of mothers had some problem (Fissure, Engorgement, Mastitis, Abscess) in breastfeeding after discharge; and 50.9% of them sought help from their relatives in order to fix the problem and only 19.3% referred to the medical team; while breastfeeding counseling centers have been launched across the country and it is probably due to insufficient educational campaigns which necessitates further working.One of the limitations of this study was no addressing to the type of cesarean section (elective or emergency), which was due to insufficient information of mothers of this issue and lack of medical documents which would be helpful if available. In the study conducted by Bahadori et al, most cesarean sections in Iran are performed without medical indication (not emergency) [35]; but fortunately, successful breastfeeding is more performed in elective deliveries 1). Biro and Dorothy found that emergency cesarean section has more negative effect on this process [5, 18].

5. Conclusions

- Implementing WHO ten steps, at all hospitals especially private ones, supporting young mothers with lower parity, medical consultation to address mothers’ nursing issues after delivery, improving the knowledge of the less educated & housewives are also important measures that should be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- This study was supported by MUMS in Iran (This study was unfunded). We are thankful of healthcare providers in health centers who helped us and Mothers who participated in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML