-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2015; 5(2): 63-72

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20150502.02

Osteopathic Manual Therapy Versus Traditional Exercises in the Treatment of Mechanical Low Back Pain

Mohammad F. Ali1, 2, Mohammad N. Selim3, Shereen H. Elwardany4, 5, Noran A. Elbehary6, 5, Akram M. Helmy7, 5

1Orthopedic physical therapy department, faculty of physical therapy, October 6 university

2Physical therapy department, college of medical rehabilitation, Qassim university, Saudi

3Physical therapy department, Elkaser Elainy Elfranssawy, Cairo university hospitals

4Physical therapy department, ELkaser Eleiny, cairo university hospitals

5Physical therapy department, college of medical rehabilitation, Qassim university, Saudi Arabia

6Basic science department, Physical therapy college, Cairo university

7Pediatric department, Physical therapy college, Cairo university

Correspondence to: Mohammad F. Ali, Orthopedic physical therapy department, faculty of physical therapy, October 6 university.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Objectives: This study was conducted to compare the efficacy of positional release technique with traditional exercises in the treatment of mechanical low back pain. Methods: Thirty two patients with mechanical low back pain their age ranged from 30-55 years with mean of (48.54±5.8) and their BMI below 30 kg/m2were randomly distributed into two equal groups. Group (A) 16 patients received infrared, ultrasound and traditional exercises. Group (B) 16 patients received infrared, ultrasound and positional release technique three sessions per week for 4 weeks. The primary outcome measures were pain, lumbar ROM and functional disabilities. Pain was measured by visual analog scale (VAS), lumbar ROM was measured by the inclinometer and functional disabilities were assessed by Oswestry disability index. Results: Group (B) had significant decrease in pain intensity level and the limitation of functional disabilities and significant increase in lumbar ROM; flexion and extension than group (A) (p <0.05). Conclusions: Positional release technique proved to be effective in reducing pain, improving lumbar range of motion and decreasing the limitation of functional disability more than traditional exercises in patients with mechanical low back pain.

Keywords: Osteopathic Manual Therapy, Traditional Exercises, Mechanical Low Back Pain

Cite this paper: Mohammad F. Ali, Mohammad N. Selim, Shereen H. Elwardany, Noran A. Elbehary, Akram M. Helmy, Osteopathic Manual Therapy Versus Traditional Exercises in the Treatment of Mechanical Low Back Pain, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 63-72. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Mechanical Low Back Pain (MLBP) is the general term that refers to any type of low back pain caused by strain on muscles of the vertebral column and abnormal stress. It accounts for 97% of cases, arising from spinal structures such as bone, ligaments, discs, joints, nerves, and meninges [35]. Among subjects experiencing MLBP, 90% have the possible recurrence of symptoms in their life due to improper follow up of Good posture, Exercises and Ergonomics [26]. Myofascial trigger points result from injured or overloaded muscle fibers leading to involuntary shortening and loss of oxygen and nutrient supply with increased metabolic demand on local tissues [10].Positional release technique or strain-counter strain technique (PRT or SCS) is a passive intervention aimed to relieve musculoskeletal pain and related dysfunction than that from taking medication [7, 8]. Derived from osteopathy, Positional Release Technique (PRT), or Strain-Counter strain (SCS), can relieve pain by relaxing tight (shortened) tissues and improving local circulation. Unlike massage and stretching, PRT is safe to apply even on damaged or inflamed tissues. If the soft tissues were painful and shortened, they can be gently placed into a position in which they are made even shorter, pain is usually temporarily removed. If that "position of ease" is maintained for a minute or so, the tight, tense muscle (and often trigger points housed there) are likely to release and relax [7, 4]." Nearly half of patients after manual therapy experience adverse events that are short-lived and minor; most will occur within 24 hours and resolve within 72 hours. The risk of major adverse events is very low, lower [5]. There is lacking in research into the neural and physiologic mechanisms of the process by which PRT alleviates somatic dysfunction. Clinicians should consider PRT as one essential tool of Osteopathic Manual Therapy (OMT) to be integrated into the overall plan to treat somatic dysfunction.There are different methods used in the treatment of (MLBP).Infrared radiation (IR) had been proven to be effective in relieving, reducing muscle spasm and disability in acute and chronic; it increases the extensibility of soft tissue, remove toxins from cells, enhance blood flow, increase function of the tissue cells, encourage muscle relaxation, and help relieve pain [32].Ultrasound (US) had been proven to be effective in increasing the range of motion and decreasing pain [31].Stretching exercises improve flexibility and improve nutrition of intervertebral disc induced by motion and partially by release of endorphins that modify the perception of pain [24].Strengthening exercises: Although exercise-based rehabilitation programs can reduce LBP intensity, alleviate functional disability, and improve back extension strength and endurance. Spine stabilization exercises for patients with spine dysfunction stresses the importance of the deep local stabilizing muscles, especially the multifidus and transverses abdominal muscles [21]. However, it is currently unclear whether positional release technique produces more beneficial effects than traditional therapeutic exercises for patients with MLBP. Until now, no study has provided which type of manual therapy is more effective in providing faster improvement regarding the reduction of pain, improvement of back range of motion and function disability and no studies compared efficacy of positional release technique with traditional therapeutic exercises in the treatment of MLBP. So, the current study was conducted to compare the efficacy of positional release technique with traditional therapeutic exercises in the treatment of mechanical low back pain.

2. Methods

- This study was conducted in the outpatient clinic of physical therapy department in New El Kaser El Eainy teaching hospital to compare the efficacy of positional release technique compared with traditional therapeutic exercises in the treatment of mechanical low back pain.Thirty two patients (25 male and 7 female) had diagnosed as MLBD, their age ranges from 30 to 55 years selected and distributed randomly into two equal groups. Group (A) 16 patients received infrared, ultrasound and traditional therapeutic exercises (stretching exercises and strengthening exercises for back and abdominal muscles). Group (B) 16 patients received positional release technique and the same modalities (infrared and ultrasound). Pain was measured by visual analog scale (VAS), lumbar ROM was measured by the inclinometer and functional disabilities were assessed by Oswestry disability index before and after12 sessions for both groups.All patients were referred by orthopedic surgeons who are responsible for diagnosis of cases based on clinical and radiological examinations. All patients signed written consent form.Inclusion Criteria:Patients had low back pain for at least 3 months ago, with moderate disability care (20-40%) determined through Oswestry LBP Disability Questionnaire, no previous episodes of LBP, able to perform (ROM) test of lumbar Spine (flexion and extension) within limit of pain and patient were not under medical treatment(analgesics and anti-inflammatory) are included in this study.Exclusion Criteria: Patients with history of previous back surgery, vertebral compression fracture, over weight person as BMI greater than 30, symptoms of vertigo or dizziness, cardiopulmonary disease with decreased activity tolerance, pregnant women, any sensory or neurological disturbance and back pain caused by viscerogenic causes are excluded in this study.Instrumentations: The primary outcome measures were pain, lumbar ROM and functional disabilities. Pain was assessed by Visual analog scale (VAS). VAS is a scale is 10cm line with 0 (no pain) and 10 (worst pain) on the other end. Patients were asked to place a mark along the line to denote their level of pain [30]. Functional disability of each patient was assessed by Oswestry disability questionnaire. It is valid and reliable [13]. It is consists of 10 multiple choice questions for back pain, patient select one sentence out of six that best describe his pain, Higher scores indicate great pain. - Scores (0-20%) minimal disability.- Scores (20%- 40%) moderate.- Scores (40% - 60%) severe.- Scores (60% - 80%) crippled.- Scores (80% - 100%) patients are confined to bed Lumbar flexion and extension ROM were assessed by universal inclinometer Fig. (1). It is a pendulum-based goniometry consisting of a 360 degree scale protractor with a counter weighted pointer maintained in a constantly vertical position, it's a hand held, circular, air or fluid disk, and it is valid and reliable to measure spinal motion [20].

| Figure 1. Universal inclinometer |

| Figure 2. Measuring lumbar flexion of the spine |

| Figure 3. Measuring lumbar extension of the spine |

| Figure 4. PRT for Quadratus lamborum |

| Figure 5. PRT for Multifudus muscle |

| Figure 6. PRT for Piriforms muscle |

| Figure 7. PRT for Gluteus Medius Muscle |

3. Results

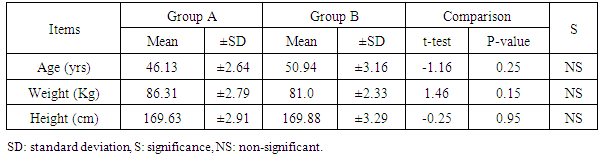

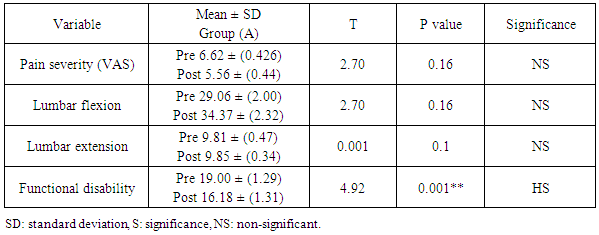

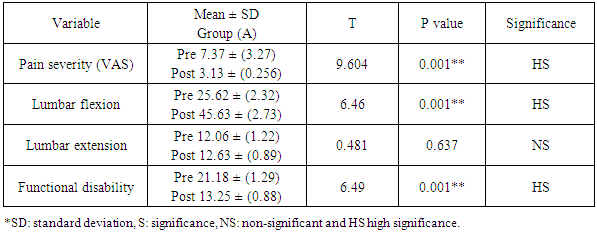

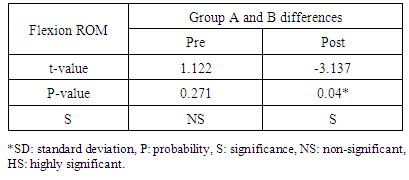

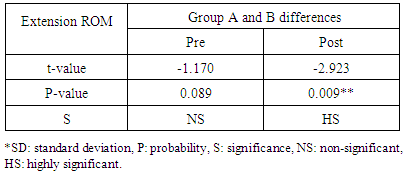

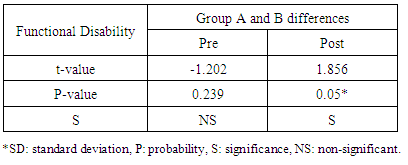

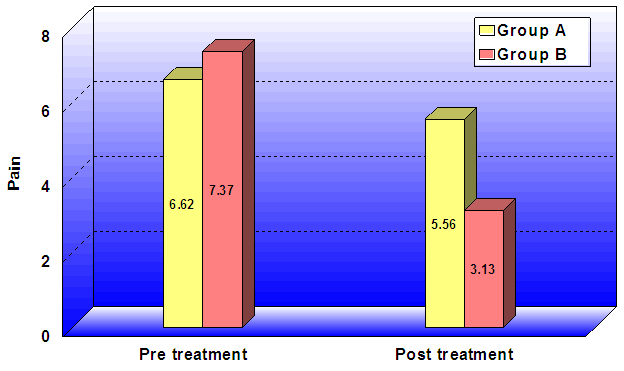

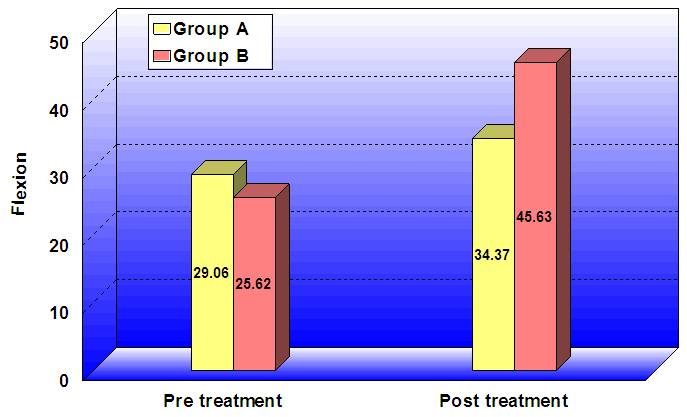

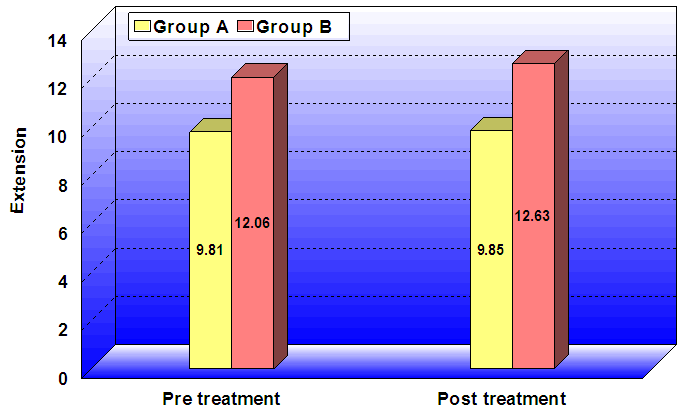

- The purpose of the study was to investigate the efficacy of positional release technique compared with traditional therapeutic exercises in the treatment of MLBP. 32 patients participated in this study; they were assigned randomly into two groups;1) Group (A) which consisted of 16 patients with mean age of 46.13(±2.644) years, mean weight of 86.31(± 2.79) kg, mean height of 169.63(±2.911) Cm. 2) Group (B) consisted of 16 patients with a mean age of 50.94 (±3.16) years, mean weight of 81.0 (± 2.33) Kg, mean height of 169.88 (± 3.29 cm).There was no significant difference between both groups in their ages, weights and height where their t and P value were (1.16, 0.25), (1.46, 0.15), and (3.29, 0.25) respectively shown in table (1). There was no significant difference in pre treatment assessment between groups in pain severity level, lumbar ROM physical function.Within group difference:Paired t-Test shows that there was not significant difference between pretreatment assessment and post treatment assessment of all dependent variables except functional disability in group (A) as shown in Tables (2) & Fig.(8,9,10). There was significant difference between pretreatment assessment and post treatment assessment of all dependent variables except lumber extension ROM in group (B) as shown in Tables (3) & Fig.(8,9,10).

|

|

|

| Figure 8. Mean and ±SD for pain severity pre and post treatment for groups (A, B) |

| Figure 9. Mean and ±SD for lumbar flexion ROM pre and post treatment for groups (A, B) |

| Figure 10. Mean and ±SD for lumbar extension ROM pre and post treatment for groups |

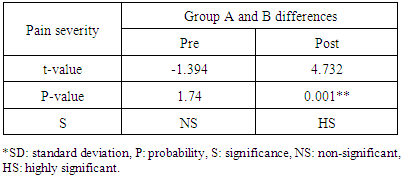

- Between group difference:Unpaired t-Test shows that there was significant difference between group (A) and group (B) in pretreatment assessment and post treatment assessment of all dependant variables in groups (A&B) as shown in Tables (4,5,6,7).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The main finding of this study was that positional release technique proved to be effective in reducing pain, improving lumbar range of motion and decreasing the limitation of functional disability more than traditional therapeutic exercises in patients with mechanical low back pain.Group (B) that received infrared, ultrasound and positional release technique showed greater significant improvement in post treatment measures than group (A) that received infrared, ultrasound and traditional therapeutic exercises (stretching and strengthening exercises for back and abdominal muscles) in reducing pain, functional disability and increasing active lumbar range of motion in both flexion and extension.Group A (Traditional therapeutic exercises)The improvement in group (A) was attributed to the following:Infrared heat effect leads to pain relief, reduction of muscle spasm and increase in sensory responses via an increase in endorphins release [25]. Heat application had been proven to be effective in relieving pain, reducing muscle spasm and disability in acute and chronic (LBP) [32].Ultrasonic therapy increases the threshold of pressure produced by pain receptors. The conduction velocity of large diameter nerve fibers (A beta) increased after application of ultrasonic while the conduction velocity of small diameter nerve fibers (A delta fibers) that are responsible for pain decreased [11]. It causes a significant tissue heat that altered the viscoelastic properties of connective tissue making it move extensible [2].Strengthening exercises for lower back muscles increased the strength of weak muscles which increase the stability of the spine which helped in reduction of pain level. In addition, strengthening exercises increased plasma concentration level of beta endorphins which result in pain reduction and increase pain threshold. Repeated muscular contraction lead to activation of the ending of A delta fibers which stimulate enkephalinergic nerve cells in the thalamus that decrease the pain and improve functional activities [37]. Strengthening exercises influence the fluid dynamics of the injured area as the stasis of the fluid and alteration of the chemical environment of the tissues which stimulate the nociceptor and cause reduction of pain [33].Dynamic strengthening exercises increased back muscle strength resulting in increased stability of lower back and reduced the load and strain in passive structures responsible for stability i.e. ligaments and joints, this improve function and range of motion [1].The role of the multifidus muscle in the stabilization of the lumbar region is being given much attention. The inner abdominal muscle thicknesses (multifidus muscle, transverse abdominal muscle) show high correlation with the stability of the lumbar region). Low activity of the inner muscles requires the outer muscles (erector spinae, musculus rectus abdominis, abdominal oblique) to compensate to keep the lumbar region stable. This compensation is one of the causes of low back pain. In the trunk structure, pathological change appears most often at the L4–L5 level. At this level the multifidus muscle is considered to be the main muscle protecting the spinal structure and improving functional stability [18].The results of this study were agreed by the results of Handa et al., [14]. Who investigated trunk muscle strength and the effect of trunk muscle exercises in patients with chronic low back dysfunction where the patients had reduction in extension strength of the trunk. Trunk extensors strengthening exercises were useful for increasing muscle strength and improving pain level in Low back Dysfunction (LBD) patients.Furthermore, the results of this study were agreed by the results of Bayramogluet al., [3]. Who examined the effect of trunk extensors strength in patients with LBD and the short-term impact of trunk extensors strengthening exercises on the same patients. Decreases in trunk extensors strength were important factors in chronic LBD, and trunk extensors strengthening program would be helpful in reducing the pain.As LBD seems to be due to shortening or contracture of the paraspinal muscles; they lead to stimulation of the nociceptors which lead to more severe pain. [34]. So, the significant reduction of pain level may be due to the effect of stretching on paravertebral muscles and other back soft tissues which reduced muscle tension and relieved the compression on muscles nociceptors and on nerve root and broke the vicious circle. Also, it decreased cellular connective tissues in paravertebral muscles and decreased muscle stiffness which lead to reduction of pain [29]. Stretching exercises had a crucial role in reduction of pain and improvement of lumbar ROM, it helps in improvement of LBD patient's functional abilities.In current study we combined both of the spinal flexion and extension exercises to ensure strengthening of both abdominal and back muscles and prevent muscular imbalance that could result from strengthening of only one group of them. Both flexion and extension exercises programs were found to be effective in reducing functional disability in chronic low back dysfunction patients. Low back pain can produce reflex muscle inhibition for paraspinal muscles to prevent movement and protect the structures. So, strengthening of these muscles reduces pain and improves function that increased trunk flexion range of motion after flexion and extension exercises due to increased flexibility and mobility of the trunk [6, 21].This finding also, has been supported by Johanssen et al., [24]. Who found that dynamic exercises for back and abdomen with stretching exercises were effective in reducing functional disability. Improvement of multifidus muscle strength (which is atrophied in low back pain) improve the functional activities.Group B (Positional release technique)The results showed highly significant improvement in all variables in group (B); the explanation of these results may be attributed to the following:As LBD seems to be due to tight and contracted muscles, where muscle fibers respond to trauma or abnormal stress by releasing calcium from the sacroplasmic reticulum or through the injured sacrolemma, which causes uncontrolled shortening activity and increased metabolism, this sustained muscle contraction decreases the blood supply, leading to an accumulation of waste products, and eventual muscle fatigue and also to the stimulation of the nociceptors which leads to more severe pain. These lead to increase muscle stiffness, thus decreasing active lumbar ROM [16]. These findings were in agreement with Howell et al., [17]. Who provides evidence in support of Korr’s [27]. It hypothesized that the characteristic restriction of motion present in somatic dysfunction was due in part to an alteration in the sensitivity of the monosynaptic stretch reflex, and could therefore be reset to restore range of motion, as reported there was an effect of PRT for patients with Achilles’ tendonitis on improving pain and restore motion. Positional release technique decreases joint and muscle pain, decreases joint swelling and stiffness and so increase mobility and a quality of life [8]. The improvement of functional ability for chronic LBD patients in this study could be attributed to analgesic effect of PRT which lead to decrease pain and improve back functions.These findings were in agreement with the study of Marc, [30] on sacroiliac diagnosis and treatment as effect of positional release and rehabilitation exercise on Gluteus Medius, Piriformis and Pubic Symphysis on low back pain. The results revealed significant improvement in pain and ROM.The result of OMT effect in this study supported by Jobn et al., [22] who compare the effect of OMT with US in chronic LBP, they found that OMT patients achieved moderate to substantial improvements which met or exceeded the Cohrance Back Review. By contrast US therapy was not efficacious in reliving back pain. This was supported in a study by Dardinski et al., [9]. That founds in a retrospective review of 20 patients suffering from chronic localized myofascial pain, the use of the PRT could be beneficial in reducing pain and improving function. The current study was in agreement with Hariharasudhan et al., [15]. Who found that both MET and SCS was effective in alleviating mechanical low back pain in terms of pain, increases in lumbar ROM, and reduces disability.The current study was not in agreement with Lewis et al., [28] who compared SCS with exercise in acute low back pain subjects and found that there is no advantage in using this method as an intervention in acute low back pain subjects. When compared with MET, SCS intervention did not achieve any substantial improvement in outcomes. The explanation of the difference in measurements outcomes may be because the difference in the sample; the current study sample was mechanical low back pain but in that study was acute low back pain.

5. Conclusions

- Positional release technique proved to be effective in reducing pain, improving lumbar range of motion and decreasing the limitation of functional disability more than traditional therapeutic exercises in patients with mechanical low back pain.

6. Recommendations

- Further studies with large sample size and applyingpositional release technique for all abdominal and back muscles responsible for MLBP are recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are thankful to Prof. Dr. Sherifa Eldebery, Dean of Qassim university and Dr. Ahmed Fawzy Ghonaim, lecturer of Mathematics, Math. Department, Helwan university for their critical contribution in the present study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML