-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2014; 4(6): 256-261

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20140406.11

Semmelweis, the Savior of Mothers and an Early Pioneer of Antiseptic

Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan)

Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan) , Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Ignaz Phillipp Semmelweis (1818-1865), Hungarian- born obstetrician while practicing medicine at the Vienna Krankenhaus noticed that most women who died after childbirth were on a ward attended by medical students who also dissected corpse. He suspected students brought infective putrid particles (germ). Semmelweis insisted the students wash their hands in chlorinated lime. In about two years, the ward’s mortality rate fell from over 10 percent to less than 1.5 percent. Although this resulted in an immediate decline, his views were heatedly attacked by then outstanding surgeons and obstetricians of Vienna, and he eventually forced to resign. He was not proved right until 1879, when Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), French chemist and father of bacteriology introduced the basis for contagion. Committed to a lunatic asylum, he died in 1865 of a blood infection.

Keywords: Semmelweis, Puerperal fever, Antiseptic

Cite this paper: Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan) , Semmelweis, the Savior of Mothers and an Early Pioneer of Antiseptic, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 256-261. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20140406.11.

1. Hint

- William E. Clarke, a practitioner from Rochester, New York endeavoured a tooth extraction under eather, in January 1842. Horace Wells (1815-1848), a Connecticut dentist was the first to use oxide nitrous as an anesthetic during surgery in January 1845. The use of ether as a surgical anesthetic was also developed by a Boston dentist, William Thomas Green Morton in 1846. Employment of ether as an anesthetic spread to Europe. Robert Liston (1794-1847), British surgeon who was renowned not least for his speed, performed the first major operation under eather anesthesia in London [1]; he called the anesthetic method a “Yankee doge [2].” Anesthesia gained approval although ether was challenged by the safer chloroform. Sir James Young Sympson (1811-1870), British obstetrician and pioneer of anesthesia in childbirth and one of the founders of gynecology, used chloroform for the first time to relieve the pains of childbirth, and it soon began to be used extensively for this purpose, even for Queen Victoria [3]. Victoria (1819-1901), Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1837-1901), and Empress of India (1876-1901), received chloroform administered by John Snow (1811-1857), brilliant British anesthetist and epidemiologist for the birth of two of her children [4].Acceptance of anesthesia made more protracted surgery feasible, but it did not by itself revolutionize surgery, however, because of the severe mortality rate from postoperative infection [5]. The menace of infection was well known.Sometimes whole wards of lying- in women were “swept away” by the disease. Epidemics also occurred in town. An epidemic in Aberdeen, Scotland, which lasted from 1789 to 1792 was studied by Alexander Gordon (1752-1799), an obstetrician from Aberdeen who proposed the contagious nature of childbed fever (puerperal fiver). He advocated disinfection of clothes of the midwives and doctors attending the mother. Many doctors and obstetricians confirmed his finding, and one who often quoted was Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), American physician and writer that studied puerperal fever and recommended hygiene precautions in hospitals for its prevention, and advocated cleaness as a means of controlling childbed fever. In 1843, he published the finest essays in the history of obstetrics which was republished in 1855 as a pamphlet entitled “Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence [6].”Holmes work was soon followed by the work of Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), Hungarian obstetrician who remonstrated against the dreadful mortality level from puerperal fever. In 1848, working in the first obstetrical clinic of the Vienna general hospital, the “Allgemeines Krankenhaus”, he observed that the first clinic, run by medical men, had a much higher puerperal fever mortality rate than the second obstetrical clinic, run by midwives. Semmelweis in keeping with the new statistical spirit of the 19th century and who assembled the facts and analysed the happening in the obstetrical wards puerperal fever. In keeping with the new statistical spirit of the 19th century, Semmelweis assembled the facts and analysed the happening on the obstetrical wards of the Vienna general hospital, “Allgemeines Krankenhaus” to prove the contagious nature of postpartum infection. He observed that the annual mortality rate on one of the wards where medical students were trained was more than 10 percent and the rate reached almost 20 percent during some months chiefly due to puerperal fever. One the ward where the midwives received instruction, the deaths rate never reached as high as three percent. He became convinced that this was caused by medical staff and students going directly from the post mortem to the delivery rooms, thereby spreading infection7. Furthermore, Semmelweis noted that the women who came down with infection were usually in a row of beds conforming to the routine of examination that day. His suspicions were further confirmed when he viewed the autopsy of his colleague Kolletschka, who had died of an infection from a scalpel wound sustained while performing an autopsy on a puerperal fever victom. Kolletschkaʼs organs showed the same changes as seen in the corpses of those dead of postpartum (occurring after childbirth) infection.

| Jakob Kollestchka Austrian pathologist who died of an infection from a scalpel wound sustained while performing an autopsy on a puerperal victom |

| Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818-1865), the savior of mothers |

2. The Highlights

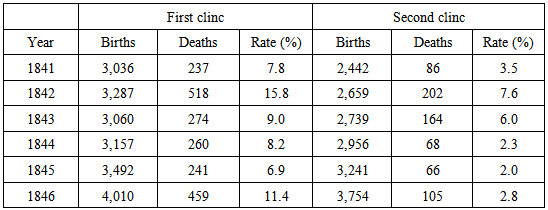

- • Ignaz’s father, Josef Semmelweis (1778-1846), was a Danube Swabian.• Maternity institutions were set up all over Europe to address problems of infanticide of illegitimate children. They were gratis institutions and offered to care for the infants, which made them attractive to underprivileged women, including prostitutes. In return for the free services, the women would be subjects for the training of doctors and midwives. Two maternity clinics were at the Viennese hospital. The first clinic had an average maternal mortality rate of about 10 percent due to puerperal fever. The second clinic’s rate was considerably lower, averaging less than 4 percent. This fact was known outside the hospital. The two clinics admitted on alternate days, but women begged to be admitted to the Second Clinic, due to the bad reputation of the First Clinic. Semmelweis described desperate women begging on their knees not to be admitted to the First Clinic. Some women even preferred to give birth in the streets, pretending to have given sudden birth en route to the hospital (a practice known as street births), which meant they would still qualify for the child care benefits without having been admitted to the clinic. Semmelweis was puzzled that puerperal fever was rare among women giving street births. “To me, it appeared logical that patients who experienced street births would become ill at least at frequently as those who delivered in the clinic. […] What protected those who delivered outside the clinic from these destructive unknown endemic influences?” Semmelweis was severely troubled that this First Clinic had a much higher mortality rate due to puerperal fever than the Second Clinic. It “made me so miserable that life seemed worthless.” The two clinics used almost the same techniques, and Semmelweis started a meticulous process of eliminating all possible differences, including even religious practices. The only major difference was the individuals who worked there. The First Clinic was the teaching service for the medical students, while the Second Clinic had been selected in 1841 for the instruction of midwives only.• The result of hand washing: The result was the mortality rate in the First Clinic dropped 90 percent, and was then comparable to that in the Second Clinic. The mortality rate in April 1847 was 18.3 percent. After hand washing was instituted in mid- May, the rates in June were 2.2 percent, July 1.2 percent, August 1.2 percent and, for the first time since the introduction of anatomical orientation, the death rate was zero in two months in the year following this discovery.• His views conflicted with the scientific and medical opinions and ideas of the time.• The theory of disease was highly influenced by humoralism (humorism), the doctrine that diseases arise from some charge in the humours or fluids of body.• As a result, his ideals were rejected by the medical community. Other more subtle, factors may also have played a role. Some doctors, for instance, were offended at the suggestion that they should wash their hands, feeling that their hands, social status as gentlemen was inconsistent with the idea that their hands could be unclean.• Specifically, Semmelweis’s claims were thought to lack scientific basis, since he could offer no acceptable explanation for his findings. Such a scientific explanation was made possible only some decades later, when the germ theory of disease was developed by Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and others. • During 1848, Semmelweis widened the scope of his washing protocol, to include all instruments coming in contact with patients in labour, and used mortality rates time series to document his success in virtually eliminating puerperal fever from the hospital ward.• From the end of 1847, Semmelweis’s work began to spread in Europe.• Semelweis and his pupils wrote letters to the directors of several leading maternity clinics describing their recent findings.• Ferdinand von Hebra the editor of a prominent Austrian medical journal, announced Semmelweise’s discovery in the December 1847 and April 1848 issues of the medical journal. Hebra claimed that Semmelweis’s work had a practical significance comparable to that of Edward Jenner’s introduction of cowpox inoculations to prevent smallpox.• In late 1848, one of the Semmelweis’s former students wrote a lecture explaining Semmelweis’s work. The lecture was presented before the Royal Medical and Surgical Society in London and a review published in The Lancet, a prominent medical journal. A few month later, another of Semmelweis’s former students published a similar essay in a French periodical. Some accounts emphasize that Semmelweis refused to communicate his method officially to the learned circles of Vienna, nor was he eager to explain it on paper. • According to his own account, Semmelweis left Vienna because he was “unable to endure further frustrations in dealing with the Viennese medical establishment.”• In a textbook, Carl Braun, Semmelweis’s successor as assistant in the first clinic, identified 30 causes of childbed fever; only the 28th of these was cadaverous infection. Other causes included conception and pregnancy, uremia, pressure exerted on adjacent organs by the shrinking uterus, emotional traumata, mistakes in diet, chilling, and atmospheric epidemic influences. The impact of Braun’s views are clearly visible in the rising mortality rates in the 1850s. • Ede Flórián Birly, Semmelweis’s predecessor as professor of obstetrics at the University of Pest, never accepted Semmelweis’s teachings; he continued to believe that puerperal fever was due to uncleanliness of the bowel.• August Breisky, an obstetrician in Prague, rejected Semmelweis’s book as “naive” and he referred to it as “the Koran of puerperal theology”. Breisky objected that Semmelweis had not proved that puerperal fever and pyemia are identical, and he insisted that other factors beyond decaying organic matter certainly had to be included in the etiology of the diseases.• Carl Edvard Marius Levy, head of the Copenhagen maternity hospital and outspoken critic of Semmelweis’s ideas, had reservations concerning the unspecific nature of cadaverous particles and that the supposed quantities were unreasonably small. “If Dr. Semmelweis had limited his opinion regarding infections from corpses to puerperal corpses, I would have been less disposed to denial than I am. […], and with due respect for the cleanliness of the Viennese students, it seems improbable that enough infective matter or vapor could be secluded around the fingernails to kill a patient.”

|

| The comparison of puerperal mortality rates for first and second clinics in the Vienna General Hospital, in 1841-1846 |

3. Life

- Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was born on July 1, 1818 in the Taban, an area of Buda, part of present Budapest, Hungary (then part of the Austrian Empire). He was the fifth child out of ten of a wealthy grocer family of Joseph Semmelweis (1778-1846), and Teresa Müller, daughther of the famous coach (vehicle) builder Fülöp Müller. Ignaz began studying law at the University of Vienna in 1837, but by the following year, he switched to medicine, and was awarded his medical degree in 1844. After failing to obtain an appointment in a clinic for internal medicine, he studied obstetrics. His outstanding teachers included Karl von Rokitansky who was the first to differentiate lobar from lobular pneumonia, Joseph Skoda who correlated physical signs with pathological lesions, and Ferdinand Hebra, German great dermatologist.

| Semmelweis’s book, “Etiology, concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever.” |

4. Conclusions and Impact

- Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis Hungarian obstetrician and advocate of asepsis for prevention puerperal sepsis, studied childbirth fever, its causes and spread and introduced strict hygiene measures to reduce mortality rate. He demonstrated that the death rate due to puerperal fever could be decreased if doctors, students and stuff washed their hands. In this way, puerperal (childbirth) fever was brought under control since 1847, and many medical advances were made on hospital wards.Nevertheless, most surgeons were hostile to his finding from autopsies of deceased women. They also showed a confusing multitude of physical signs, which emphasized the belief that childbirth fever was not only one, but many different, yet unidentified diseases. His finding also ran against the conventional wisdom that infections were caused not by contact but by miasmata in the air, emanations given off by non- human sources. Adherents of such views therefore gave priority to ventilation and prevention of ever crowding as preventive measures. Therefore he was not proved right until 1879, when Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), French chemist and father of bacteriology helped formulate the modern germ theory of disease. On the whole his work had a practical impact comparable to that of Edward Jenner’s introduction of cowpox inoculations to prevent smallpox.

Note

- 1. A comparable position today in a United States hospital would be “chief resident.”

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML