-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2014; 4(6): 216-222

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20140406.04

Psychological Predictors of Post Examination Failure Depression among Preclinical Medical and Dental Students in Ibadan Nigeria

Adebayo Oluwole1, Oladayo Sunday Oyedun2

1Department of Guidance and Counselling, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

2Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oladayo Sunday Oyedun, Department of Anatomy, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

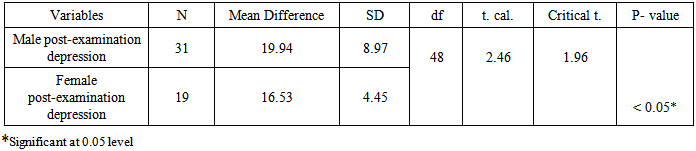

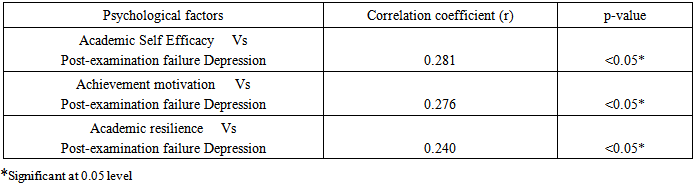

Objectives: This study examined the influence of gender and some psychological factors on pre-clinical medical students' post-examination depression in University of Ibadan. Methods: The study employed a descriptive survey research design using ex-post facto type. Fifty pre-clinical medical students who were academically depressed in the University of Ibadan were selected for the study using proportionate random sampling technique. Academic Self-Efficacy Scale, Achievement motivation scale, Academic Resilience Scale and Goldberg's Depression test were used for collecting data. Four hypotheses were tested at 0.05 significant level. Data were analyzed using multiple regression and t test statistics. Results: It is evidenced from the result that males (Mean = 19.94; ± 8.97) have higher scores in the post-examination depression than the females (Mean = 16.53; ± 4.45). Also, there was significant positive correlations between academic self efficacy and post-examination depression (r = 0.281; p < 0.05). There was significant relationship between achievement motivation and depression (r = 0.276; p < 0.05). Further, the result revealed that there is significant positive relationship between academic resilience and post-examination depression (r = 0.247; p<0.05). Conclusions: Medical school administrators and curriculum experts should pay special attention to the pre-clinical medical students' well being in order to guarantee their academic fulfillment.

Keywords: Academic Self Efficacy, Academic Resilience, Achievement Motivation, Post-Examination Depression, Pre-Clinical Medical Students

Cite this paper: Adebayo Oluwole, Oladayo Sunday Oyedun, Psychological Predictors of Post Examination Failure Depression among Preclinical Medical and Dental Students in Ibadan Nigeria, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 216-222. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20140406.04.

1. Introduction

- In developing countries such as Nigeria, the pre-clinical medical students are facing serious challenge of bleak future as a result of inability to pass the qualifying examination into the clinical class. Medical and dental schools in Nigeria run a two-part curriculum over a period of five years. In the preclinical segment, both medical and dental students are taught Anatomy, Physiology and Biochemistry over a period of two years after which they write a qualifying examination (Part I MB;BS, BDS examination) to cross to the clinical segment. This transition examination constitutes a major concern to the preclinical students as failing on two occasions translates to withdrawal from the course. Unlike in the pre-clinical years, the curriculum for the medical and dental students differs in the clinical years as they rotate through different specialties. This study examined depression in medical and dental students who failed the Part I MB;BS and BDS examinations. In the Past, research indicates that mental health problems of university students are on the increase. The college years are also a time during which most students get their first opportunity to engage in serious independent study without parental intervention. Given the potential stress students may experience while attempting to cross to the resident years in college of medicine in addition to the high amount of examination anxiety and family pressure to succeed, pre-clinical students may be at increased risk for psychological problems such as depression compared to same aged peers in other climes [1-3]. This study adds to the existing literature and expands on the relatively small research base pertaining to gender and psychological factors contributing to post-examination depression among the pre-clinical medical students population. In addition, this study investigated the prevalence of depression based on gender among the pre-clinical students.The theoretical underpinning of this study was Beck’s Cognitive Model on Depression. Beck’s cognitive theory was used to operationalize depression [4, 5]. There are three specific notions to explain depression in Beck’s cognitive model. These notions are the cognitive triad, schemas, and cognitive errors. Beck’s theory also suggests that depression is the activation of three major cognitive patterns that lead individuals to view themselves, the world, and the future in a negative manner, known as the negative triad [5, 6]. In sum, a negative view of the world, self, and future is likely to have an impact on academic self efficacy, achievement motivation and academic resilience of the students irrespective of their gender.Most studies have found clear gender differences in the prevalence of depressive disorders. Typically, studies report that women have a prevalence rate for depression up to twice that of men [7, 8]. For example, Kessler et al [9] reported that women in the United States are about two-thirds more likely than men to be depressed, and a national psychiatric morbidity survey in Britain showed a similar greater risk of depression for women [10]. Gender differences in depression appear to be at their greatest during reproductive years [7]. Nazroo et al [11] explained that women may be more likely to have been socialized to express dysphoria in response to stress and men may be more likely to have been socialized to express anger or other forms of acting out. In support of this, studies have shown that expected gender differences in depressive disorders were balanced out by higher male rates of alcohol abuse and drug dependency [9, 10]. Conversely, individuals with low self efficacy level feel threatened when they encounter difficult situations and try to avoid them. They are less committed to the set goals and may avoid cognitively oriented goals and tasks, they are quick to attribute failure to lack of capacity to persist in the face of adversities [12]. Self efficacy has also been prominent in studies of psychological and educational construct such as attribution of success and failures [13, 14]. Bouffard-Bouchard [15] observed that in spite of the constructs assumed predictive power, however, research on the relationship between self efficacy and academic performance is although growing still limited.Understanding the factors that affect achievement is important because motivation affects achievement and level of occupation [16]. Murray [17] described achievement motivation as the desire to accomplish something difficult to overcome obstacles and attain a high standard; to excel oneself. Burger [18] indicated that high-need achievers are moderate risk takers, have an energetic approach to work, and prefer jobs that give them personal responsibility for outcomes.Resilience in psychology refers to the idea of an individual’s tendency to cope with stress and adversity. This coping may result in the individual bouncing back to a previous state of effectiveness or using experience of exposure to adversity to produce a steeling effect and individual’s personal factors, environments and behaviour [19]. However, there are several alterable factors that have been found to influence resiliency in children. According to Bernard [20]. There are four personal characteristics that resilient children typically display: Socio competence; Problem solving skills; Autonomy and A sense of purpose. McMillan and Reed [21] described four other factors that appears to be related to resiliency; Personal attributes such as motivation and goal orientation; Positive use of time (e.g. home-work completion on task behaviour and participation in extra-curricular experience; Family life (e.g. family support and expectations), and, School and classroom learning environment (i.e. facilities, exposure to technology, leadership and over all climate).Against this backdrop, four objectives are raised for this study. 1. To examine the difference in the post-examination depression mean scores of male and female students;2. To determine the relationship between academic self efficacy and post-examination depression among the pre-clinical students;3. To investigate the relationship between achievement motivation and depression among the pre-clinical students;4. To establish the relationship between academic resilience and post-examination depression among the pre-clinical students.

2. Method

- The study employed a descriptive survey research design using ex-post facto type. Using the Beck's Depression Inventory, seventy year-2 pre-clinical medical and dental students who wrote and failed the end of pre-clinical examination once or twice in the University of Ibadan were screened for the study. Fifty respondents were selected using proportionate random sampling technique. That is, 25 students each were selected from Departments of Medicine and Dentistry respectively. This is to ascertain that the two groups do have equal representation in the sample size.Ethical Permission Guiding the StudyEthical approval was obtained, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to the study.InstrumentationThe instruments were used to collect data for the study. All the instruments do have high validity which make them relevant and useful for the study.Academic Self-Efficacy Academic Self-Efficacy was measured using the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale by Schwarzer [22] was adapted for use in this study. The scale was tailored for use among the University students. The scale comprised 10 items. The 10 items were scored as follows: 1 = Not at all true 2 = Hardly true 3 = Moderately true 4 = Exactly true.The points scored on all items were summed up to give participant’s score on the scale. The items were coded because there are both negative and positive statements which should be reversed. Scores on the scale ranged between 10 and 40. The psychometric property of the instrument was pilot-tested by administering the scale on two sets of 15 students from two non medical departments, on two separate occasions of three weeks interval. The test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.77.Achievement motivationThe short form of the Ray achievement motivation scale [23-25] was adopted and used. It was a 7 item short form of the Ray Achievement Motivation scale. When tested on seven samples from Sydney, London, Glasgow and Johannesburg it showed reliabilities of over .70 when applied to English speakers. It is also balanced against acquiescent response set and has validities well comparable with other longer scales. General population norms obtained in the four countries revealed the English, Scots and Australians to have similar levels of achievement motivation with South Africans significantly higher. The items of the short form of the Ray-Lynn AO scale. Response options are "Yes", (scored 3), "?" (scored 2), "No" (scored 1). Items marked "R" are to be reverse-scored (e.g. "1" becomes "3") before addition to get the overall score. For the current study, a pilot study was carried in order to tropicalise it for use, a high reliability was found using Cronbach’s alpha (α = .68).Academic Resilience The academic resilience questionnaire (ARQ) constructed and validated by Connor and Davidson [26] was extracted as a measure of resilience questionnaire. The scale comprises 25 items, each rate on a 5-point likert. The scale has been found to be valid and reliable, with Cronbach ‘s alpha of 0.89, [27, 26].DepressionThis 18-question self-test by pioneering researcher Dr Ivan K Goldberg highlights signs and symptoms associated with depression. Screening test scoring are: 0-9 No Depression Likely; 10-17, Possibly Mildly Depressed; 18-21, Borderline Depression; 22-35, Mild-Moderate Depression; 36-53, Moderate-Severe Depression, and 54 and up, Severely Depressed. For diagnostic purpose, the higher the number, the more severe the depression.Procedure and Data AnalysisAll the participants completed the four questionnaires on Academic Self-Efficacy Scale, Achievement motivation scale, Academic Resilience Scale, Goldberg's Depression test and demographic variables (age, gender and no of times they failed the pre-clinical examination). The reliability and internal consistency (item-total item correlation) for the questionnaires was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The values are as follow: Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (α = 0.84), Achievement motivation scale (α = 0.76), Academic Resilience Scale (α = 0.73) and Goldberg's Depression test (α = 0.80). The statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 18.0. For statistical analysis, p-values lower than .05 were considered statistically significant. Four hypotheses were tested at 0.05 significant level. Data were analysed using multiple regression and t test statistics.

3. Results

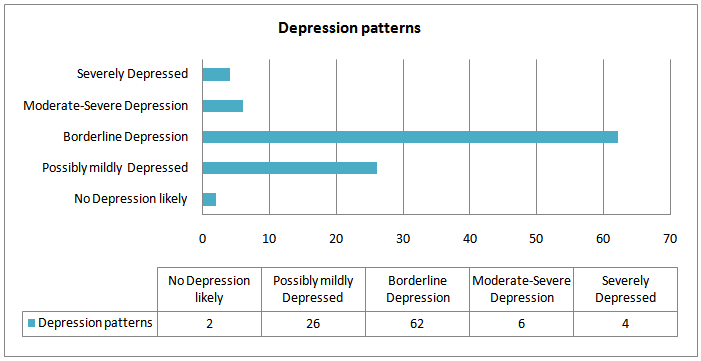

- Fifty Preclinical students (25 medical and 25 dental students) were selected for the study. 62% (n-31) of the participants were males while 38% (n-29) were females.Fig: 1 summarizes the level of depression among the studied group. 2% (1) of the participants may not be depressed; 26% (13) were possibly mildly depressed; 62% (31) were suffering from borderline depression; 6% (3) were experiencing moderate-severe depression while 4.0% (2) were severely depressed.

| Figure 1. Descriptive information on the level of depression among the participants in the study |

|

|

4. Discussion

- The findings from this study (Table 1) revealed that there is a significant difference between male and female pre-clinical students in their post-examination depression of male and female students. The finding affirmed that male students have higher depression mean score compared to their female classmates. This finding buttressed that of Centre for Disease and Control report [28] that men in the U.S. are about four times more likely than women to commit suicide. A staggering 75% to 80% of all people who commit suicide in the U.S. are men. Though more women attempt suicide, more men are successful at actually ending their lives [29]. A common cause for this unsavory end is depression. It is more likely that male pre-clinical students are exposed to undue pressure to succeed at all cost in Medicine and medical related courses because several people in Nigeria believe that it is their sure way of breaking the poverty cycle in their families.Nazario [29] also explained that understanding how men in our society are brought up to behave is particularly important in identifying and treating their depression. Depression in men often can be traced to cultural expectations. Men are supposed to be successful. They should rein in their emotions. They must be in control. These cultural expectations can mask some of the true symptoms of depression. Instead, men may express aggression and anger -- seen as more acceptable "tough guy" behavior.Though depression has been perceived as 'woman's disease' across culture, study such as this has busted this myth because Medicine and Dentistry courses have been long stereotyped as men's career paths most Nigerian societies. as a result of this misconception, many male medical students are just trying to fit into their expected male role of belonging to medical sciences professions. This could bring about cognitive dissonance in this male medical students whereby they are facing conflicts between their career choices and the career expectations of their parents and the extended society. This study also found a significant relationship between academic self efficacy and post-examination depression among the pre-clinical students in the University of Ibadan. Many studies examined academic efficacy impact on school performance [30, 31]. Few studies have focused on possible relations between academic efficacy on young adult depression, and even fewer have focused on the specific cognitive mechanisms linking self-regulatory efforts and depression. Scott [32] established a relationship between cognitive self-regulatory processes and depressive symptoms among the Native American youths. Moreover, Bandura [33] hinted that one major pathway to depression occurs when individuals possess a low sense of self-efficacy for performing the actions required to realize valued goals. There is strong support for a relationship between efficacy judgments and depression in adults. The implication of this is that the lower the self efficacy of an individual, the more the tendency to be vulnerable to depression. Among the pre-clinical medical students who were underperforming in their course of study, it is only those who are confident that they can overcome that adversity and realize valued futures are the ones most likely to develop successfully and competently.The present finding in this present study indicated that there is significant correlation between achievement motivation and depression among the pre-clinical students. Although this study does not dichotomise participants into achievement motivation compartments of performance goal and mastery approaches, several studies have done this. According to Dykman [34], the negative effects of exposing performance-oriented students to challenging math exercises would be manifested with elevated depression, anxiety, and negative affectivity and with loss in self-esteem. Dykman [34] proposed that following a challenging task, performance-oriented individuals would show elevated anxiety and may also show signs of depression when performance is low.In the light of this, it could be inferred that majority of the students experiencing post-examination depression may likely fall into the category of performance goal individuals, hence, they lack the deep processing, concentration, the use of optimal strategies, and persistence which are attributes of mastery-oriented students. Whereas, attending to extrinsic rewards and/or performance outcomes has previously been found to relate negatively to effort, particularly for such challenging tasks [35]. Based on this fact, it could be deduced that the depressed medical students might have lost the value they attach to Medical profession and reduced their effort in achieving success in their examinations. Thus, the value and importance associated with the pursuit of a goal may be the critical element in attaining positive achievement outcomes and in resisting depression.The study showed that there is a significant relationship between academic resilience and post-examination depression. A key determining factor in academic success in any discipline, particularly medicine is resilience. Resilience is vital to positive adjustment to college life, attending to reading, practical, and routine exercises as well as giving all it takes to succeed despite poor social support, decayed infrastructures, high cost of textbooks and non-stimulating environment such as Nigeria. As elusive as the concept of resilience is, there is agreement among scholars that it depends largely on individual, community, and institutional factors [36].It is unfortunate that most medical students are not very much aware of the amount of stress that awaits them in the medical college. Those that cave in easily will possibly be liable to experience depression. This is so since resilience suppose to help medical students to reject the potential negative effect caused by adversity or risk factors such as examination failure that could make them vulnerable to depression and suffered diminished well being.The present studies have both advantages and limitations. An advantage is the insight gained into the existing nexus among gender, achievement motivation, academic efficacy and academic resilience on post examination depression of pre-clinical students. A limitation of the study was an inability to mount intervention strategies in managing the depression of the students. Also, the sample size of the participants is relatively small which could affect the generalization estimates of this study. Previous study on causes of post examination failure depression in Nigerian medical students is rare but direct observation reveals fear of losing a rewarding profession, lack of family support and lack of support program for medical students withdrawn from the department as likely causes. This differs from the situation in developed countries where causes of depression in medical students have been identified as competitive environment, work overload, constant pressure of examination and previous history of depressive disorders [36]. The difference in the causes of depression may be attributed to difference in cultural perception of failure, level of organization students counseling structure and level of poverty.Medical students with post-examination depression may benefit from psychotherapy which is geared towards the changing students’ negative perception of thought pattern, encouraging positive thinking and ensuring sustained support counseling.

5. Conclusions

- This research contributes to the existing theoretical aspects of achievement motivation, resilience, academic self efficacy and post-examination depression. The results could be applied in improving medical education in Nigeria and rest of the world by extension. Also, counseling support programmes are essential for medical students in order to help them discover insight on how their self-perceptions could affect their performance.Given that depression is attributed to motive dispositions and goal setting, depression prevention should start with the early school experiences. Teachers may structure their environment to promote interest in academic tasks and value mastery and improvement rather than competence. Structuring the classroom environment in a way that encourages the pursuit of multiple goals may also prove to be adaptive. Admission procedure for students into medical college in Nigeria is faulty because there is increased advocacy for selection based on cognitive capabilities. It is essential that non-cognitive (attitudinal and motivational) capabilities and interview screening which include scenario assessment be encouraged. For example, using some of the psychological tools which test for trait resilience, achievement motivation and self efficacy would be a useful part of admissions screening and this will help in reducing academic failures and wastage among medical trainees.The possibility that self efficacy and resilience can be strengthened by interventions after the early years of life is an attractive concept for health professional training, and has not been well explored particularly in the medical education literature. The development of self efficacy and resilience has been discussed as a mechanism through which depression could be reversed so as to bring about improved well-being among the medical students. Counselling psychologists should be partnered with for self efficacy and resilience-promoting program to be integrated effectively into the medical education training.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML