-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2014; 4(5): 139-149

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20140405.01

Improving Compliance of Hand Hygiene Practices among Intensive Care Unit Employees in AL-Istishari Hospital in Jordan

AlaDeen Mah’d Alloubani1, Weaam F. Jeorg Taktak2, Ayad Ahmed Hussein3, Rasha M. AlZanoun4, Hazar Najib Rabadi4, Tina Joyce5

1Nursing, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia P.O. BOX 741

2University of Petra, Amman, Jordan

3Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplantation Program, King Hussein Cancer Center, Amman, Jordan

4Institute of Leadership, Royal College of Surgeon Ireland, Dublin and Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

5Institute of Leadership, Royal College of Surgeon Ireland, Dublin

Correspondence to: AlaDeen Mah’d Alloubani, Nursing, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia P.O. BOX 741.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

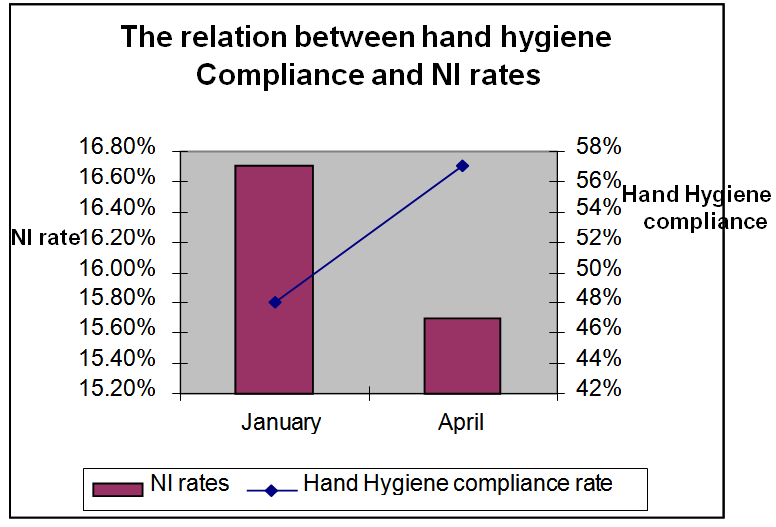

Hand hygiene (HH) is the most significant factor for the improvment of practices and reduction of microorganism transmission to patients, visitors, and health care workers, yet compliance rates remaining low.This study aims to improve the compliance of intensive care unit (ICU) staff in hand disinfection; either by washing or rubbing with alcohol-based solution.We analysised the HH compliance of ICU staff at Al-Istishari hospital in Jordan over a period of four months (December 2008-April 2009). A total of 24 study participants were observed to have a high ratio of HH compliance rate after removing gloves (76%).This prospective, interventional study employed an exploratory mixed qualitative-quantitative method. The study was conducted between December 2008 and April 2009 in the ICU at Al-Istishari Hospital, Amman, Jordan. The Hand Washing Questionnaire (HWQ) and 80 h of observations were used to measure and evaluate the compliance of HH practices among ICU employees.The effective compliance to HH practice was as low as 28% in January, rising to 32% in April; a total improvement of 4%. This was accompanied by a corresponding improvement in the rate of nosocomial infection (NI). The NI rate dropped by 5.6% over a short period; from 16.7% in January 2009 to 11.1% in March 2009.We identified an inverse relationship between HH compliance and NI rates.These findings suggest that the NI rate of ICUs can be reduced by relatively inexpensive strategies. We propose that a national HH program should be implemented in all healthcare sectors in Jordan.

Keywords: Hand Hygiene Compliance, Nosocomial Infection, Intensive Care Unit, Al-Istishari Hospital, and Jordan

Cite this paper: AlaDeen Mah’d Alloubani, Weaam F. Jeorg Taktak, Ayad Ahmed Hussein, Rasha M. AlZanoun, Hazar Najib Rabadi, Tina Joyce, Improving Compliance of Hand Hygiene Practices among Intensive Care Unit Employees in AL-Istishari Hospital in Jordan, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 139-149. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20140405.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Nosocomial infection (NI), also called Hospital-Acquired Infection, is an infection that has its onset during the hospitalization and was not present or incubated at time of admission. It occurs within: 48 hours of hospital admission, 3 days of discharge or 30 days after a surgical operation (World Health Organization, 2002).The WHO studies and others found that the highest prevalence of NI occurs in intensive care units (ICU). Not surprisingly, infection rates are higher among patients with more severe underlying diseases that necessitate ICU admission. These infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates (Makhoul et al., 2002; Stoll et al., 2004).The NI is usually acquired while doing simple tasks by the health care worker, like pulling patient up in bed, touching equipment like bed side rail or over bed tables and other monitors. Most of these infections can be avoided with relatively cheap strategies, such as adhering to recommended infection prevention practices, especially hand washing (Kampf & Kramer, 2004; Lam et al., 2004; Yildirim et al., 2008).According to United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the "hand washing is the single most important means of preventing the spread of infection." However; the idea of cleaning hands with some antiseptic emerged in the 19th century, when up to 25% of women during childbirth were dying from puerperal sepsis (Helder & Latour, 2009; O’Grady et al., 2002). Within three months after instituting a strict policy of hand washing with a chlorinated antiseptic solution, mortality rates dropped by 10 to 20 fold. Researchers have examined many of methods and groupings of methods to enhance hand washing (Gould et al., 2007; Naikoba & Hayward, 2001). Despite hand hygiene has been proven to decrease the prevalence of infections in healthcare facilities (Yildirim et al., 2008), health care workers often do not wash their hands when recommended (Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Pittet et al., 2000). NI is a serious consideration of prevention of infection in all of the worlds, but in developing countries they are the main source of preventable disease and death (Sanil Kumar, 2012). Rates of NI are markedly higher in many developing countries, especially for infections that can be preventable (WHO, 2002). In these countries, NI rates are high because the absence of supervision, inadequate prevention of infection practices, inappropriate use of limited resources, and overcrowding of hospitals.This study is aiming to improve the compliance of the working staff in the ICU regarding disinfecting their hands, either by washing or rubbing them with alcohol-based solution. Additionally, to assess the correlation between the hand hygiene compliance rate and the NI rate.Importance of the study: We think such a study is an important one from different perspectives;A- For the hospital: 1- In terms of Cost: decreasing the rate of NI can contribute in one way, or another to reduce the cost of:• Length of hospitalization.• Treatment with expensive medications (e.g. antibiotics)• Use of other services (e.g., laboratory tests, X-rays and transfusions).2- Competitive advantage: improving the patients’ outcome will lead to decreasing the hospital morbidity and mortality rates. B- For the patients:1- Controlling NI will affect: • Patients’ conditions and outcome. • Treatment cost. • Patients’ satisfaction.C- For the staff:1- Controlling the rate of NI will improve:• Safety.• Staff job satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

- This prospective, interventional study employed an exploratory mixed qualitative-quantitative method; the most popular approach used to facilitate scientific decisions includes quantitative and qualitative methods (Neuman, 2005; Polit & Beck 2006).The quantitative and qualitative methods proved valuable to discover and describe essential issues within the different fields (Hudacek, 2008; Burns & Grove, 2007). Both methods offered significant scientific knowledge that responded to many questions (Creswell, 2005). Quantitative and qualitative methods could be complementary to one another (Burns & Grove, 2007; Neuman, 2005).This study was conducted in 2 phases: a Four months pre-intervention period from December, 2008 to establish a baseline of hand hygiene compliance rate and post-intervention period from April, 2009 to measure the improvement in the hand hygiene compliance rate.

2.2. Setting

- This study was conducted between December 2008 and April 2009 in the ICU at Al-Istishari Hospital, Amman, Jordan. It is a relatively new hospital and, not surprising; it is paying some attention to infection control issue. AL-Istishari hospital is a general hospital that contains 108 beds. The ICU has 11 beds, five of which are isolated ones. Hand hygiene facilities are available in ICU; there are six sinks and four-alcohol-based-solution dispensers. The hospital adopts some useful initiatives regarding this issue, through conducting continual medical education sessions to the staff. It was found by the infection control committee at AL-Istishari hospital before starting this study that the rate of overall healthcare workers’ compliance with hand hygiene procedures scored 51% at the ICU, whereas the rate was 40% in the other departments.

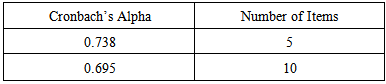

2.3. Instruments

- The Hand Washing Questionnaire (HWQ) and 80 hours observations were used in this study to measure and evaluate the compliance of hand hygiene practices among intensive care unit employees. The HWQ contains 12 items. The first five items assessed the compliance on a four-point rating scale.The anchors used by the HWQ include 1 = All the time, 2 = 1 out of 2 times, 3 = 1 out of 4 times, and 4 = Not at all.Items six to ten assess the staff knowledge about the two-hand hygiene methods effectiveness. The last two items evaluate the suggestion and the reasons which prevent the staff from practicing hand hygiene.Eighty hours observation was conducted using the direct observation method (the ‘gold standard’).

2.4. Population and Sample

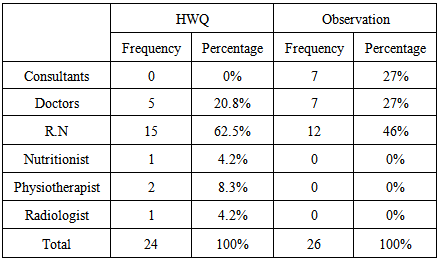

- A convenience sampling technique was used to obtain the desired sample size. At minimum, 50 participants were needed to improve confidence in the results. HWQ was distributed for Five doctors, 15-staff nurses, two physiotherapists, one-nutritionist and one radiologist.A random sample of 12 nurses, seven doctors and seven consultants were observed each time. Observed nurses were all working at 1:1 nurse to patient ratio.

|

2.5. Implementation

- The implementation process was held through many activities, the chronological sequence of which is as follows:§ Dec 25th, 2008, The first visit and the meeting with the medical director and head nurse of ICU, and infection control nurse§ Jan 14th-19th, 2009, The first observation§ Jan 28th, 2009, The first questionnaire§ Feb 1st, 2009, Increasing the number of the alcohol-based solution dispensers § Feb 5th, 2009, The second visit, poster installation and the staff meeting§ Feb 25th, 2009, The third visit and the first lecture§ Mar 23rd, 2009, The fourth visit and the second interactive lecture§ Apr 18th, 2009, The second questionnaire§ Apr 19th-24th, 2009, The second observationThe above activities are classified into five main elements; which are: 1- Visits & lectures: The first visit was held on Dec. 25th; 2008 starting at 10.00 am and lasting for almost two hours. Four-team members visited the hospital and met the medical director of the hospital initially to introduce the team, explain the project importance, objectives and plans, in addition to the official permission and agreement to start and facilitate the implementation process. The second meeting was held in the same day with the infection control nurse and head nurse of ICU. The importance of the study was explained in detail during that meeting, emphasizing the importance of cooperation between all parties. The meeting was very valuable; specifications about the hospital in general and the ICU, and its atmosphere in specific shaped some ideas, and reshaped others in our previously set plan. The visit ended by an exploratory tour to the ICU, to help form a clearer picture of the current situation and the reasonably aimed at one. The second visit was held on February 5th, 2009, started at 6:00 pm and lasted for about two hours. The visit was scheduled in the afternoon to ensure the attendance of most of the nurses (nurses change shifts at 7:00 pm). Three-team members attended the meeting in addition to 15-ICU nurses, five doctors, two physiotherapists, one radiology technician, and one nutritionist and infection control nurse. The purpose of the meeting was to re-explain the importance and objectives of the study and to promote the staff involvement and commitment to the implantation of the project. The proper hand washing technique was clearly and carefully demonstrated in that meeting also. The unwanted effects of improper procedure were thoroughly explained and discussed. The third visit was held on February 25th, 2009 to give a lecture which was scheduled earlier. The lecture consisted of a Power Point presentation along with the movie. It lasted for about 1.5 hour. There were 27 attendees, 16 of which were ICU nurses, four physicians, infection control nurse, head nurse of ICU, four nurses from other departments and 1-radiology technician. The main purpose of the lectures was to demonstrate the most important steps that might help in reducing the hospital-acquired infections through improving hand hygiene practice. An interesting Interaction was noticed among all attendees, and all questions and inquiries were clearly answered by our team members. It was noticed through that visit that the staff members have very good knowledge about hand hygiene, but it seemed that they were not practicing it in a proper and effective way. The fourth visit took place on March 23rd and lasted for 2.5 hours. The visit was aimed to follow in the previous hand hygiene practice implementation, enhancing the active involvement of all staff, and also an interesting lecture about the last updated information regarding hand hygiene practice was given. There were 29 attendants, 13 of them were ICU nurses, eight nurses from other departments, infection control nurse, 2-radiology technicians, 1-physiotherapist and 3 physicians, in addition to the head nurse of ICU. The presentation was enforced by using more multimedia tools which showed the proper technique, and the effect of the improper practice. It was clearly noticed that there were more attendants as well as more interaction during the lecture compared to the former one. Our team and the attendants interacted closely, and felt that as we were spreading out, motivational and enthusiastic atmosphere for everyone. 2- Questionaire:An eleven-item questionnaire was distributed to most of the involved staff at two phases; in the beginning and toward the end of the project implantation. The questions addressed different factors related to hand hygiene practice and knowledge.The questions were clearly explained in full details by our team to reduce ambiguity. We made it clear for the staff that there are not any personal identification information in the questionnaire, in order to reduce any discomfort that could affect the honesty of their answers. We also demonstrated that the proper results of this questionnaire will help us in recognizing the real causes behind the improper hand hygiene practice or knowledge. The first questionnaire was distributed on the 28th of January, 2009 to a total of 24 recipients, including 15 ICU nurses, 5 doctors, 2 physiotherapists, one-radiology technician and one nutritionist. The same questionnaire was distributed at the 18th of April, 2009 to 24 recipients; for the same staff. The answered questionnaires were collected four days after the distribution at the two occasions. 3- Observational study: An eighty hours observation in the ICU was done by our team member who works there as an ICU nurse. The observation was divided equally into two phases. The first one took place between January 14th and January 19th. And the second started on April 19th and ended on April 24th. The interval between the two phases gave enough room for the other interventions to have a measurable impact (the maximum of our limited allowed time). The persons selected for observation were closely monitored to detect both their compliance to hand hygiene practices and the effectiveness of those practices. It is to be noted here that our observer had another implementation responsibility. He communicated continuously with the members of the staff explaining them the importance of the project; not only for the patients in the unit, but also for them to ensure their safety and indirectly increase their job satisfaction. It was a challenging attempt to change their behaviour, increasing their compliance, and overcoming the expected resistance to change which might occur due to any reason. 4- Posters’ introduction:Two kinds of posters were installed in the facility on February 5th, 2009: 1) Instructing Posters, which explain the steps of the proper hand washing technique. Those posters were attached at the top of each of the 3 sinks. 2) Reminding Posters were installed at the main door of the ICU, and also at different places inside the ICU to remind the staff and visitors about the importance of proper hand washing. 5- Technical interventions: Two main changes were introduced to the ICU at the beginning of the project implementation:A- The alcohol dispensers were increased from 3 to 13, one dispenser by each bed (a total of 11 beds), one at the ICU entrance door and one between the patients’ rest room and that of the staff. Increasing the number of dispensers served on two aspects. First, it increased the availability, and the accessibility, reducing the impact of the claimed effect of the shortage in disinfectants. Second, the presence and distribution of this number of dispensers worked as a reminder for the working staff, dropping down the “forgetting” excuse of the staff members.B- Disposable paper towels also were installed at the top of each sink to prevent contamination of hands when turning off the tap.Most of the facility modifications took place during the third visit in February, except for the introduction of the added alcohol dispensers which was done earlier at the end of December 2008.

3. Statistical Analysis

- The statistical analysis was performed using a one-sided P-value with a 95% confidence level and comparing proportions as percentages. All the statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) System for Windows, version 21.

4. Results

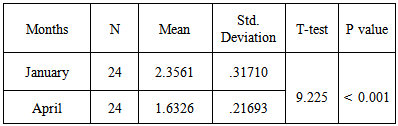

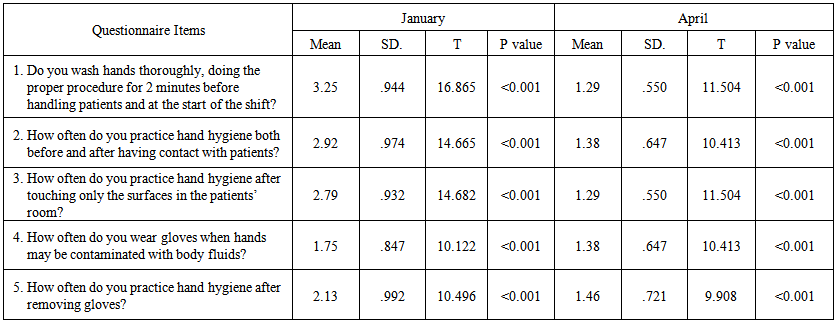

- 1- The questionnaire:Upon analysing collected data from the questionnaires at the beginning and the end of the project, the following observations can be shown below:The table number 2 depicts that there is a strong relationship of compliance of hand hygiene in the hospital as the values shown in the table is significant; there is a significant impact of hand hygiene compliance among Health care workers in Al-Istishari hospital in Jordan. The significant relationship is shown by the P-value less than 0.01 and T value 9.225 through the t-test for equality of means.

|

| Table (3). Means, Standard deviations, and T-Test value for the first five items of the hand washing questionnaire |

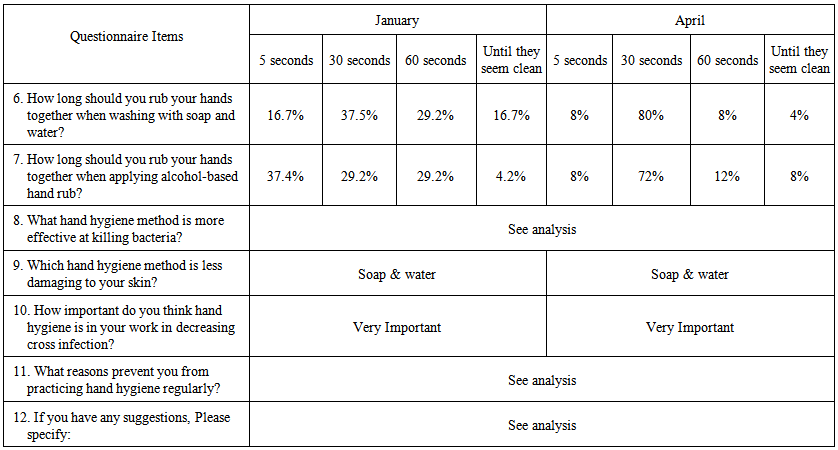

| Table (4). Percentage value of the hand washing questionnaire items |

|

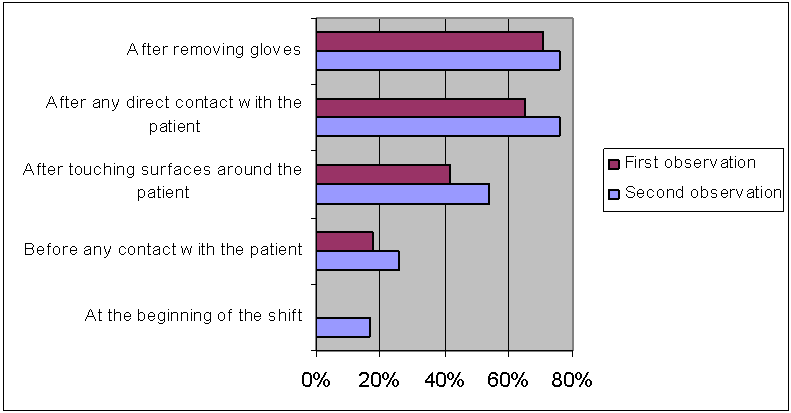

| Figure (1). The ratio of compliance to hand hygiene practices |

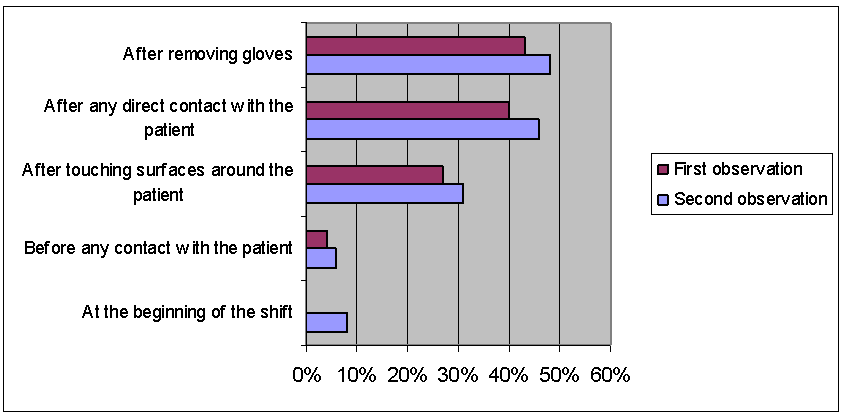

| Figure (2). The mean ratio effective hand hygiene practice at different shift activities |

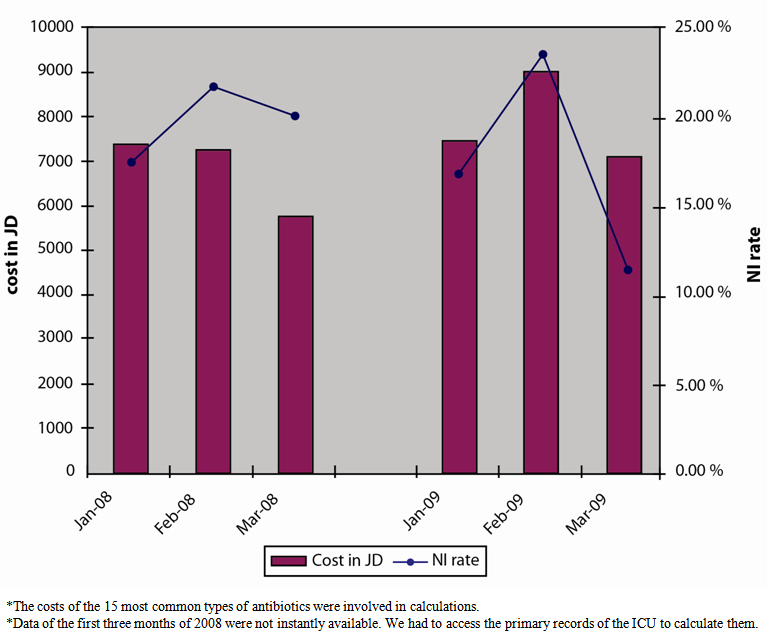

| Figure (3). The relation between NI rate and cost of disinfectant and antibioti |

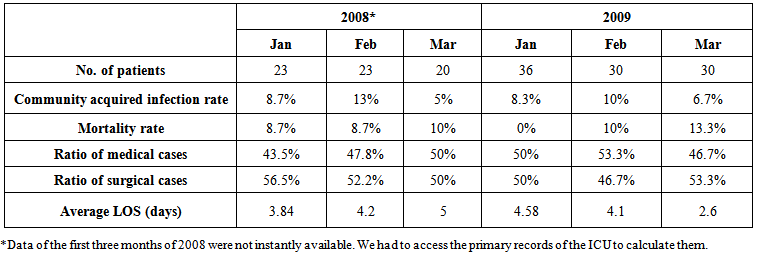

| Table (6). NI rates and related statistics |

| Figure (4). The relation between hand hygiene compliance and NI rates |

5. Discussion

- Hand hygiene is broadly assumed to be an efficient way to decrease nosocomial infection (NI) in hospitals, especially in intensive care units (ICUs). NI is frequently viewed as indicating non-compliance with hand-washing practices. The data reveal useful knowledge and high awareness levels of the working staff in the ICU of Al-Istishari Hospital in (Jordan) concerning hand hygiene practices. Analyses of the questionnaire showed higher levels of compliance. However, observations conducted at the ICU reflected a different point of view. The inconsistencies in the results may be attributed to measuring two distinct entities: cognitive knowledge and actual behaviour. Pessoa-Silva et al. (2005) and Jenner et al. (2005) hypothesized that social cognitive models may help to elucidate the impact of human behaviour. Behavioural science may additionally inspire new directions in the research field.These same aspects apply for the knowledge of the staff about the effectiveness of hand hygiene practices. Their knowledge, although below expected levels, was reasonable compared with the findings of both observations. Previous studies reported baseline compliance rates ranging from 28–44% (Lam et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2003). In this research, the baseline compliance rate for hand hygiene was as high as 48–57%. This finding reveals that most Health care employees perceive the necessity of hand hygiene. The highest compliance scores were seen after Health care professionals removed their gloves. This result could be due to one of two main reasons: A- Gloves are usually worn before conducting an invasive procedure on a patient or where contact with secretions or fluids from the patient’s body is expected. B- Powder is left on the hands upon the removal of gloves. Both reasons explain why Health care professionals wash their hands after wearing gloves. Even the effectiveness of hand hygiene practices was the highest after removing gloves; the second highest effectiveness was after direct contact with patients. It is possible to draw a conclusion that these results are due to a selfish attitude on the side of the staff; they are concerned more about themselves and less about their patients and their safety. This result is in agreement with a hospital-wide, cross-sectional study that recommended that Health care employees practice hand hygiene for their own protection, rather than to protect their patients (Novoa, 2007). Another study that supports our findings was conducted in the ICU by O’Boyle et al. (2001), who showed that hand hygiene compliance (evaluated through direct observation) was the highest ‘after completion of care and remove the gloves’ (87.1%) and ‘after direct contact with body substances’ (87.1%). Complete hand washing also included washing the wrists, finger tops, thumbs, and between the fingers. Lam et al. (2004) evaluated hand-washing methods with soap and water and also observed an enhancement after an intervention. The improvement in the compliance rates seen via an observational study toward the end of the project implementation was 9%, which was a substantial rise in such a short period of time. We believe that the staff responded well to the implementation activities, which indicates that the staff have the ability to create dramatic improvements in staff practices in general and in hand hygiene in particular. Our understanding of a higher hand hygiene compliance rate among employees after the intervention was comparable to the compliance rates monitored in many ICUs in the United States (Pessoa-Silva, 2007). More time and effort is necessary to demonstrate the real effectiveness of project implementation. As a general rule, human behavioural changes necessitate long periods of time and significant effort. The improvement in the corresponding rates of NI over a short period of time was 5.6% (from 16.7% in January to 11.1% in March). Although this figure exceeds the predicted value slightly, several main points can be highlighted here: • The primary NI rate provided by the infection control program was a general figure for all of 2008 and the rate was 33%; our measured rate in April 2009 was 15.5%. This time duration is a short period over which to comment on the actual reduction in the rate of NI, yet there is an encouraging, improving trend. Repeated awareness of appropriate hand hygiene is necessary, and different creative methods are important for renewing this message among Health care employees. Single, multifaceted interventions seem to have a more prolonged impact (Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Huang et al., 2002; Salemi et al., 2002). The incurred costs were proportionally related to the NI rates in 2009, an issue of significant importance for hospital management, cost of treatments and patients’ outcomes.

6. Conclusions

- This study presented that hand hygiene compliance observation, in addition to the other orientation tools used in our campaign, is a useful tool for improving hand hygiene compliance in ICU at Al-Istishari private hospital in Jordan. Enhancing hand hygiene concept among population in the whole society, to be reflected in the technical work among Health care workers. This will lead to an easier and better adherence to the instructions as it becomes a natural habit of daily human activities. A more Interventional study with a longer period is necessary to support the observed enhancements in the nosocomial infection rates associated with the improved rate of hand hygiene compliance in ICU. To sustain this current level of enhancement, Proper training of the all health care workers about hand hygiene and Periodic re-evaluation and re-training of all health care workers regarding hand hygiene practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- We would like to thank Dr. Osama Atari (Medical director of the hospital) for his invaluable assistance and support, which helped us in completing this research through various stages.Our sincere thanks also go to the Mrs. Hanan Albakri (Head nurse of Intensive care unit) for her cooperation during the study period. Our thanks and appreciation also goes to infection control staff for willing to help us. Lastly, thank you once again for your great support in the successful completion of this research.

Declarations of Interest

- “We hereby certify that this material, which we now submit for your Journal is entirely our own work and there is “No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.”

Funding Statement

- Received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors, or support in the form of equipment or other assistance.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML