-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2014; 4(4): 108-113

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20140404.02

Application of Forrest Classifiction in the Risk Assessment and Prediction of Rebleeding in Patients with Bleeding Peptic Ulcer in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Akande Oladimeji Ajayi1, Ebenezer Adekunle Ajayi1, Taiwo Hussean Raimi1, Patrick Temi Adegun2, Samuel Ayokunle Dada1, Olatayo Adekunle Adeoti1, Michael Abayomi Akolawole1

1Department of Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B 5355, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

2Department of Surgery, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B 5355, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Akande Oladimeji Ajayi, Department of Medicine, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B 5355, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

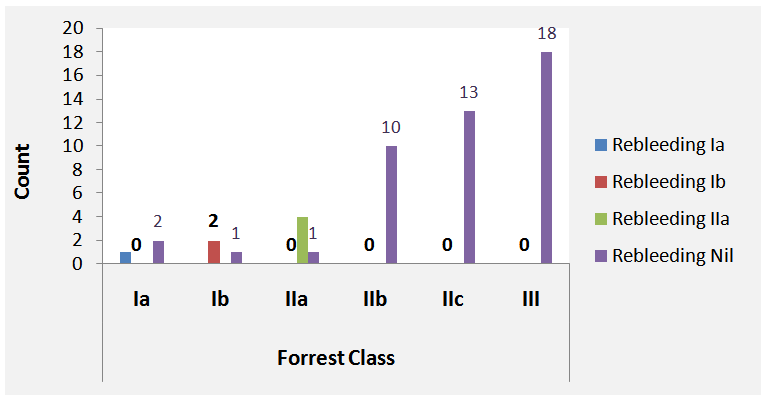

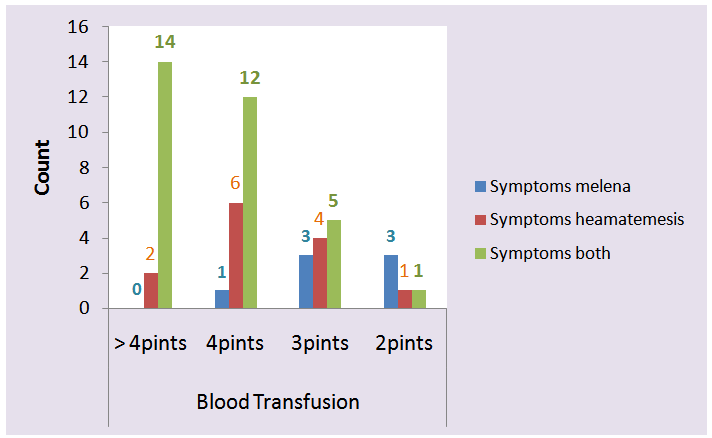

Aim and Background: Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most frequent cause of non variceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Rebleeding is a frequently observed complication of peptic ulcer bleeds. Recurrence of hemorrhage is one of the most important factors affecting the prognosis, and early prediction and treatment of rebleeding. The aim of this study was to assess if Forrest classification is still useful in the risk assessment and prediction of rebleeding after acute UGIB in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria and to compare it with other results in literature.Materials and Methods: Fifty two consecutive patients who presented with clinical signs and symptoms of acute peptic ulcer bleeding between 1st of January 2009 and 31st of December 2011 were enrolled into the study. All underwent emergency endoscopy within 24 hours of admission. Forrest classification was used to categorize the various stigmata of active or recent bleeding seen at endoscopy. The study was carried out at the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. An ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the institution’s Ethical and Research committee and all the patients gave written consent for the study. SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was applied for statistical analysis using the t-test for quantitative variables and χ2 test for qualitative variables. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if P value was less than 0.05. Results: The mean age of the studied population was 53.92±12.14 years (age ranged from 29-78 years) while the female: male ratio was 1: 2.5. The presenting symptoms were; melena in 13.5% (7), haematemesis in 25% (13) and coexistence of both melena and haematemesis in 61.5% (32) of the patients. Findings at endoscopy were stratified using Forrest classification into: Forrest class IA; 3 (5.8%), Forrest class IB; 3 (5.8%), Forrest class IIA; 5 (9.6%), Forrest class IIB; 10 (19.2%), Forrest class IIC; 13 (25%) and Forrest class III; 18(34.6%). Rebleeding was found after initial stabilization and cessation of bleeding in 33.3% of those in Forrest class IA, 66.7% in Forrest class IB and 80.0% in Forrest class IIA. No rebleeding was found in the other classes. 30.8% of the patients had more than 4 pints of blood transfusion, 36.5% had 4 pints of blood, 23.1% had 3 pints of blood and 9.6% had 2 pints of blood.In the Univariate analysis, Forrest class was statistically significant to the occurrence of rebleeding (χ2 = 91.135, p = 0.001, α = 0.005 i.e. 95% confidence interval). Also, blood transfusion was found to be statistically significant to the severity of symptoms (χ2 = 17.979, p = 0.006, α = 0.005, i.e. 95% confidence interval). Conclusions: This study demonstrates that Forrest classification is still useful in predicting rebleeding of peptic ulcers; however, it does not predict mortality arising from UGIB. It is recommended that patients with UGIB be referred to centres with endoscopy facilities for initial assessment using Forrest classification to predict the risk of rebleeding and the need for urgent interventions as major bleeding episodes can be fatal for the high risk patients. This study is limited by the number of patients studied; hence a multicentre study is advocated to validate the conclusion made in this study in Nigeria.

Keywords: Forrest classification, Peptic ulcer disease, Rebleeding

Cite this paper: Akande Oladimeji Ajayi, Ebenezer Adekunle Ajayi, Taiwo Hussean Raimi, Patrick Temi Adegun, Samuel Ayokunle Dada, Olatayo Adekunle Adeoti, Michael Abayomi Akolawole, Application of Forrest Classifiction in the Risk Assessment and Prediction of Rebleeding in Patients with Bleeding Peptic Ulcer in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 108-113. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20140404.02.

1. Introduction

- The annual incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is 48–160 events per 100,000 adults in the US [1], while in Europe, the annual incidence in the general population ranges from 19.4 - 57.0 events per 100,000 individuals [2-3]. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most frequent cause of non variceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding (NVUGIB), being responsible in about 50% of cases, with an overall mortality rate of 10 to 14% [4-5]. Recurrence of hemorrhage is one of the most important factors affecting the prognosis, and early prediction and treatment of rebleeding would improve the outcome in such patients [6]. Several clinical factors and endoscopic signs have been found to be associated with further hemorrhage.Rebleeding is a frequently observed complication of peptic ulcer bleeds which often prevent early discharge from hospital [7]. Studies have estimated the incidence of continued bleeding and/or rebleeding and mortality following NVUGIB to range between 2% and 17% [8–11], with an average 30-day mortality of 8.6% after peptic ulcer hemorrhage [12]. Prediction of the risk of recurrent bleeding in the patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding has been the focus of attention in the last decades. In the United States, studies have shown that around 4 million people have a recurrent form of the peptic ulcer disease [13]. Haemorrhage stops spontaneously in about 80% of UGIB with medicaments therapy only, while in 10-20% cases after initial haemostasis patients have rebleeding [14]. Rebleeding was defined as a new episode of bleeding during hospitalisation, after the initial bleeding had stopped, that manifested as: recent haematemesis, hypotension (systolic pressure lower than 100 – 90 mmHg), tachycardia, (rapid pulse higher than 100 – 110 beats per minute), melaena, transfusions requirement greater than 4 - 5 units and the level of haemoglobin lower than 100 g/l in the first 72h from the initial endoscopic treatment [14-15].Forrest classification [16] developed about four decades ago groups patients with acute UGIB into high- and low-risk categories for mortality. This classification is also significant for the prediction of rebleeding and in the evaluation of the endoscopic intervention modalities [16]. It is equally used to identify patients who are at an increased risk for rebleeding and mortality. The aim of this study was to assess if Forrest classification is still useful in the risk assessment and prediction of rebleeding after acute UGIB in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria and to compare it with other results in literature.

2. Materials and Methods

- All the fifty two patients who presented with clinical signs and symptoms of acute peptic ulcer bleeding, i.e. haematemesis, melena or both and anaemia between January 2009 and December 2012 were included in this study. The study was carried out at the Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Relevant clinical information such as age, gender, clinical presentations, history of smoking, alcohol use, previous gastrointestinal haemorrhage, ingestion of non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) / anticoagulants, and associated co-morbidities were obtained from the patient.After initial resuscitation and stabilization with intravenous fluids and blood transfusion, they all underwent emergency endoscopy within 24 hours of admission. Forrest classification (Table 1) was used to categorize the various stigmata of active or recent bleeding seen at endoscopy [16]. Patients with Forrest classes IA, IB, IIA and IIB were treated by endoscopic injection with epinephrine (1/10 000) and intravenous Rabeprazole, while those with Forrest classes IIC and III were treated with intravenous Rabeprazole only. All patients with signs and symptoms of rebleeding after the initial stabilization and therapy (recurrent haematemesis, melena, hypovolaemia and 2 g/dl decrease in haemoglobin level) underwent a repeat endoscopy and surgery. An ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the EKSUTH Ethical and Research committee and all the patients gave written consent for the study. SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was applied for statistical analysis using the t-test for quantitative variables and χ2 test for qualitative variables. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if P value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

- Fifty two patients were enrolled into this study comprising 15 (28.9%) females and 37 (71.1%) males. The female: male ratio was 1: 2.5. The mean age of the studied population was 53.92±12.14 years (age ranged from 29-78). Majority of the patients were in the age group 41-70 years (Table 2). The presenting symptoms were; melena in 13.5% (7), haematemesis in 25% (13) and coexistence of both melena and haematemesis in 61.5% (32) of the patients. The risk factors identified for PUD in the study populations were; NSAIDS (30.8%), H. pylori (38.5%), alcohol (17.3%) and peppery/spicy food intake in (13.5%). These risk factors were however, not statistically significant to the occurrence of rebleeding (χ2 = 4.079, p = 0.906, α = 0.005 i.e. 95% confidence interval).

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Correlation of Forrest class to rebleeding |

| Figure 2. Relationship between symptoms and blood transfusion |

4. Discussion

- Rebleeding is considered the most important independent risk factor for mortality. It has been shown to cause more than 5 times higher mortality rate in patients with initial bleeding and those in whom bleeding stopped spontaneously.Several scoring systems such as Forrest classification, Rockall and Blatchford have been developed and described in literature to predict and stratify patients with UGIB [16, 17]. While Forrest classification is based only on endoscopic assessment, Rockall evaluates clinical, biochemical and endoscopic variables for the prediction of rebleeding as well as outcome of UGIB. Blatchford on the other hand, evaluates certain clinical and biochemical variables without endoscopic evaluation of bleeding lesions for the prediction of clinical outcome. Forrest classification has the advantage of being easy to carry out and causes little additional burden for the patients. Its main disadvantage is that it does not predict mortality.In this study, acute UGIB occurs more frequently in the male than the female gender and this was found to increase according to age and in tandem with the findings in the study of Longstreth et al [18]. The risk factors identified for PUD in this study populations were; NSAIDS (30.8%), H. pylori (38.5%), alcohol (17.3%) and peppery/spicy food intake in (13.5%).Applying Forrest classification, the following were found at endoscopy; three (5.8%) in Forrest class IA, three (5.8%) in Forrest class IB, five (9.6%) in Forrest class IIA, ten (19.2%) in Forrest class IIB, thirteen (25%) in Forrest class IIC and eighteen (34.6%) in Forrest class III. Major stigmata of haemorrhage was found in 21 (40.4%) of the patients compared to the 58.3% obtained in the study of Lanas et al [19]. Endoscopic injection of epinephrine (1/10,000) combined with intravenous Rabeprazole was carried out in those with major stigmata of haemorrhage (40.4%) while intravenous Rabeprazole was administered only in 59.6% of the patients (those in Forrest classes IIC and III). Lanas et al [19], found in their study that the most commonly used procedures for the treatment of acute NVUGIB were epinephrine injection (24.6%), and injection sclerotherapy (11.5%) and that utilization of these procedures vary; Spain (36.0% and 24.3% respectively) and in Greece (19.9% and 2.0% respectively). Rebleeding rate in this study was highest in Forrest class IIA (80%) and lowest in Forrest class IA (33.3%), contrary to the findings in the study of Hadzibulic et al [20] where rebleeding rate was highest in Forrest class IIB. The smaller percentage obtained in Forrest class IA in this study compared to cases described in literature [7, 21], might be due to the relatively small number of the patients enrolled. Overall, the rebleeding rate in this study was 13.5%, this is comparable to the 13.3% and 14.6% reported in the studies of Guglielmi et al [6] and Barkun et al [22] respectively, and slightly lower than the 16.5% obtained by Hadzibulic eta al [20]. No rebleeding was reported in Forrest IIB, IIC and III in this study compared to the rebleeding rate of 15.6% in IIC and 6.5 % in III obtained in the study of de Groot et al [23]. Majority (72%) of the rebleeding occurred between 24-48 hours of the initial haemorrhagic episode while in the remaining 28%, rebleeding time ranged between 3-7 days. No rebleeding was observed after one week from the initial episode. The overall mortality rate in this study was 5.8% (33.3% [1/3] in both Forrest classes IA and IB, 25% [1/4] in Forrest class IIA and 0% in the other Forrest classes). This overall mortality rate compares favourably with the rates of between 3.8-15% reported in other studies [6, 23-27]. One of these deaths was from haemorrhagic shock prior to surgery while the remaining two were from causes unrelated to gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopic treatment with epinephrine was effective in 66.7% of our patients compared to the 86.8% success obtained in the study of Guglielmi et al [6]. The difference in the success rate of endoscopic treatment in the two studies might be due to the fact that while epinephrine injection was combined with intravenous Rabeprazole in our study, epinephrine injection and 1% polidocanol were combined in the other study. Ten patients (19.2%) underwent emergency surgical operations and seven of these were as a result of rebleeding.In this study, Forrest class was statistically significant to the occurrence of rebleeding (p = 0.001), this is in agreement with that reported in literature [6, 28-29]. Also, blood transfusion was found to be statistically significant to the severity of symptoms (p = 0.006). The risk factors identified for PUD in the study populations were; NSAIDS (30.8%), H. pylori (38.5%), alcohol (17.3%) and peppery/spicy food intake in (13.5%). These risk factors were however not statistically significant to the occurrence of rebleeding (p = 0.906). The significance of applying Forrest classification to predict rebleeding in undeveloped countries where endoscopy facilities are not widely available cannot but be emphasized. In these countries, most acute UGIBs are managed empirically with proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists thereby making precise inspections and prediction of rebleeding almost impossible.

5. Conclusions

- This study demonstrates that Forrest classification is still useful in predicting rebleeding of peptic ulcers; however, it does not predict mortality arising from UGIB. It is recommended that patients with UGIB be referred to centres with endoscopy facilities for initial assessment using Forrest classification to predict the risk of rebleeding and the need for urgent interventions as major bleeding episodes can be fatal for the high risk patients. This study is limited by the number of patients studied; hence a multicentre study is advocated to validate the conclusion made in this study in Nigeria.

References

| [1] | Button, L. A. et al. 2011, Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther., 33: 64–76. |

| [2] | Lau, J. Y. et al.2011, Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion, 84:102–113. |

| [3] | Bardhan, K. D., Williamson, M., Royston, C. & Lyon, C. 2004, Admission rates for peptic ulcer in the Trent region, UK, 1972–2000: changing pattern, a changing disease? Dig. Liver Dis., 36: 577–588. |

| [4] | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC.1996, Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut, 38: 316–321. |

| [5] | Imhof M, Schroders C, Ohmann C, Roher H.1998, Impact of early operation on the mortality from bleeding peptic ulcer – ten years’ experience. Dig Surg, 15: 308–314. |

| [6] | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Sandri M et al.2002, Risk Assessment and Prediction of Rebleeding in Bleeding Gastroduodenal Ulcer. Endoscopy, 34: 771–779. |

| [7] | Laine L, Jensen DM.2012, Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol, 107: 345–360. |

| [8] | Muller T, Barkun AN, Martel M. 2009, Non-variceal upper GI bleeding in patients already hospitalized for another condition. Am J Gastroenterol., 104:330–339. |

| [9] | Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, et al.2008, Predictive factors of mortality from nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol., 103:1639–1647. |

| [10] | Viviane A, Alan BN.2008, Estimates of costs of hospital stay for variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United State. Value Health, 11:1–3. |

| [11] | Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, et al.2010, Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol., 105: 84–89. |

| [12] | Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, et al. 2011, Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion, 84:102–113. |

| [13] | Longstreth GF.1995, Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage:a populationbased study. Am J Gastroenterol., 90: 206-210. |

| [14] | Sung JJ, Mossner J, Barkun A et al. 2008, Intravenous esomeprazole for prevention of peptic ulcer re-bleeding: rationale/design of Peptic Ulcer Bleed study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther., 27: 666–677. |

| [15] | Wong SKH, Yu LM, Lau JYM, Lam YH, Chan ACW, Ng EKW, Sung JJY, Chung SCS. 2002, Prediction of therapeutic failure after adrenaline injection plus heater probe treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. Gut, 50:322-325. |

| [16] | Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ.1974, Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet, 2:394-397. |

| [17] | Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford MA. 2000, Risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet, 356:1318–21. |

| [18] | Longstreth GF, Feitelberg SP.1998, Successful outpatient management of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: use of practice guidelines in large patients series. Gastrointest Endosc., 47:219-222. |

| [19] | Lanas A, Aabakken L, Fonseca J, Mungan Z et al. 2012,Variability in the Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Europe: An Observational Study. Advances in therapy, 29 (12):1026-1036. |

| [20] | Hadzibulic E, Govedarica S. 2007, Significance of Forrest classification, Rockall’s AND Blatchforf’s risk scoring system in prediction of rebleeding in peptic ulcer disease. Acta Medica Medianae, 46(4):38-43. |

| [21] | Laine L, Peterson WL.1994, Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med, 331: 717–727. |

| [22] | Barkun A, Sabbah S, Enns R, Amstrong D et al. 2004, The Canadian Registry on non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and endoscopy: Endoscopic haemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with improved outcomes in a real-life setting. Am Coll of Gastroenterology, 99: 1238-1246. |

| [23] | De Groot NL , van Oijen MGH, Kessels K, Hemmink M et al. 2014, Reassessment of the predictive value of the Forrest classification for peptic ulcer rebleeding and mortality: can classification be simplified? Endoscopy, 46: 46–52. |

| [24] | Saeed ZA, Cole RA, Ramirez FC et al.1996, Endoscopic retreatment after successful initial hemostasis prevents ulcer rebleeding: A prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy, 28: 288–294. |

| [25] | Bourienne A, Pagenault M, Heresbach D et al. 2000, Stude prospective multicentrique des facteurs pronostiquTs des hTmorragies ulcTreuses gastroduod Tnales. Gastroenterol Clin Biol., 24: 193–200. |

| [26] | Rutgeerts P, Rauws E, Wara P et al. 1997, Randomised trial of single and repeated fibrin glue compared with injection of polidocanol in treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer. Lancet, 350: 692–696. |

| [27] | Brullet E, Campo R, Calvet X et al. 1996, Factors related to the failure of endoscopic injection therapy for bleeding gastric ulcer. Gut, 39: 155–158. |

| [28] | Chow LW, Gertsch P, Poon RT, Branicki FJ. 1998, Risk factors for rebleeding and death from peptic ulcer in the very elderly. Br J Surg., 85: 121–124. |

| [29] | Corley DA, Stefan AM, WolfM et al. 1998, Early indicators of prognosis in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol., 93: 336–340. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML