-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2014; 4(1): 19-22

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20140401.04

Cardiac Output Changes in Hepatorenal Syndrome

Khaled El Karmouty, Nanees Adel, Reham Al Swaff, Eman Elbedwehy

Internal Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Nanees Adel, Internal Medicine department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Background: Recent studies suggest that the development of hepatorenal syndrome occurs in the setting of a reduction in cardiac output, indicating that the progression of circulatory and renal dysfunction in cirrhosis is caused not only by splanchnic vasodilatation but also by a reduction in cardiac output. Aim of the study: This study aimed to evaluate cardiac output changes in Egyptian patients with HCV related decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome. Patients and Methods: cardiac output changes were evaluated in 100 Egyptian patients with HCV related liver cirrhosis who were recruited from the hepatology outpatient clinic and were classified into 3 groups as follows: group I included 20 patients with compensated liver cirrhosis, group II included 40 patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites, group III included 40 patients with hepatorenal syndrome.Results: insignificant higher mean cardiac output values were found in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and patients with hepatorenal syndrome as compared to the patients with compensated cirrhosis.Conclusion: patients with HCV related decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome have normal or high cardiac output values which seem to be insufficient to maintain adequate tissue perfusion.

Keywords: HRS, Cardiac output, Cirrhosis

Cite this paper: Khaled El Karmouty, Nanees Adel, Reham Al Swaff, Eman Elbedwehy, Cardiac Output Changes in Hepatorenal Syndrome, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 19-22. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20140401.04.

1. Introduction

- Liver cirrhosis is associated with a wide range of cardiovascular abnormalities. These abnormalities include hyperdynamic circulation which is characterized by an increase in cardiac output and a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance[1].A complex interplay between the splanchnic, systemic, and renal circulations takes place once portal hypertension is established[2].The reduction of the effective arterial blood volume and renal impairment which occur in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites are consequences of not only progressive arterial vasodilatation but also cardiac systolic dysfunction [3-5].There seems to be a complex and bidirectional interaction between the heart and the kidneys, and different observations have suggested that a type of cardiac dysfunction known as cirrhotic cardiomyopathy significantly contributes to the pathophysiology of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)[5].Recent studies suggest that the development of hepatorenal syndrome occurs in the setting of a reduction in cardiac output, indicating that the progression of circulatory and renal dysfunction in cirrhosis is caused not only by splanchnic vasodilatation but also by a reduction in cardiac output. This finding suggests that HRS may be the consequence of a fall in cardiac output in the setting of marked splanchnic vasodilatation[3, 4, 6].

2. Aim of the Study

- This study aimed to evaluate cardiac output changes in Egyptian patients with HCV related decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome.

3. Patients and Methods

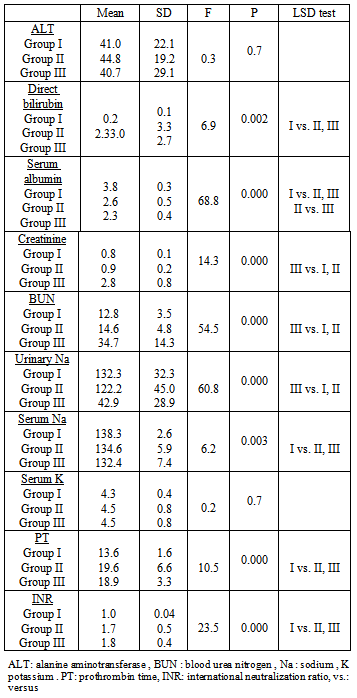

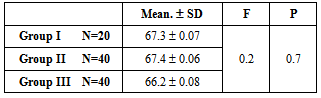

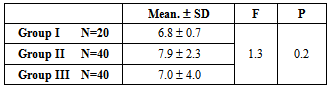

- This study was conducted in the gastroenterology and hepatology unit, internal medicine department, Ain Shams University Hospital Cairo, Egypt. 100 Egyptian patients with HCV related liver cirrhosis were recruited and were classified into 3 groups as follows: group I included 20 patients with compensated liver cirrhosis, group II included 40 patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites, group III included 40 patients with HRS.Diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome was established according to the International Ascites Club’s diagnostic criteria of Hepatorenal syndrome (2007)[7]:1. Cirrhosis with ascites.2. Serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl.3. No improvement in serum creatinine (decrease to a level of <1.5 mg/dl) after at least 2 days with diuretic withdrawal and volume expansion with albumin. The recommended dose of albumin is 1 g/kg of body weight per day up to a maximum of 100 g/day.4. Absence of shock.5. No current or recent treatment with nephrotoxic drugs.6. Absence of parenchymal kidney disease as indicated by proteinuria < 500 mg/day, microhematuria <50 RBC/high power field and normal renal ultrasonography.All the studied patients were subjected to the following:• History taking, clinical examination, laboratory investigations including: liver function tests, renal function tests, prothrombin time& INR, CBC, alpha feto-protein, fasting and 2h post prandial blood glucose and viral markers (HBsAg, HCVAb and HIV antibody using ELISA technique)• Diagnostic paracentesis was done for group I and II for assessment of ascetic fluid cells, chemical analysis (total proteins, glucose, albumin and LDH), bacteriological and pathological examination.• Radiological investigations including: Abdominal ultrasonography, Chest X ray and Electrocardiography.• Eccho cardiography (Aloka SSD 4000, Japan) using 2-4MHZ convex probe, front-end technology including a 12-bit A/D converter, wide-band super high-density (W-SHD) transducers, Pixel Focus and a Pure harmonic detection (Pure HD) feature. All patients were examined in supine and left lateral recumbent positions and had trans-thoracic 2 dimensional, M mode, pulsed wave and continuous wave Doppler echocardiography. Measurements have been obtained from apical and left parasternal views according to American Society of Echocardiography recommendations. The technique was applied by the same operator who was blinded with respect to clinical and laboratory data.• Diuretic therapy was stopped at least 4 days before enrollment in the study[4].• This study was approved by the scientific and ethical committee of Ain Shams University hospital, Cairo, Egypt.• Written informed consents were signed by all patients before participating in the study.Exclusion criteria:• Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.• Patients with hereditary haemochromatosis.• Regular or excessive alcohol consumption.• Patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.• Patients with vascular hepatic disorders (Budd Chari and veno-occlusive diseases).• Patients with any form of cardiovascular and /or pulmonary disorders.• Patients with intrinsic renal disease.• Patients receiving any form of cardio-depressing drugs (including selective and non selective beta-blockers).• HIV infection.• Current intravenous drug abuse.• Patients refusing to participate in the study.Statistical methodology:The statistical analysis of data was done by using computer programs Microsoft Excel version 7 (Microsoft Corporation, NY, and USA) and SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical program. The following tests were used: calculation of the mean value and standard deviations (SD), one way Analysis of variance (ANOVA). The probability of error (P) was expressed as following: P-value > 0.05: non-significant, P-value ≤ 0.05: significant, P-Value <0.01: highly significant

4. Results

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- Hepatorenal syndrome is estimated to occur in 10% of patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites[8]. Recent studies suggest that cardiac dysfunction precedes development of hepatorenal syndrome[6].Reduction of cardiac output is a very relevant event in the clinical course of cirrhosis as it is an independent predictor of hepatorenal syndrome[9].The present study aimed to evaluate cardiac output changes in patients with hepatorenal syndrome and revealed an insignificant difference between patients with hepatorenal syndrome, patients with decompensated cirrhosis and patients with compensated cirrhosis as regards cardiac output values. This result agrees with Salerno, et al.2008[10] who stated that cardiac output values in patients with HRS may be low, normal or high, but it is insufficient for the patient’s needs because of reduced peripheral resistances.In discordance with the previous reports Angeli and Merkel. 2008[11] observed a higher cardiac output values in patients with cirrhosis and HRS than in cirrhotic patients without HRS. They interpreted the discrepancies between their study and previous studies which reported that in HRS cardiac output was similar or reduced as compared to patients with cirrhosis without HRS to the fact that effective circulating volume does not depend only on vascular peripheral resistance, but also on a series of other factors which are prone to be altered in patients with cirrhosis[12]. The results of the current study also disagree with Ruiz-del-arbol, et al.2005[4] who found a positive correlation between the development of hepatorenal syndrome and the reduction in cardiac output and stroke volume. This discrepancy may be related to the differences in the inclusion criteria between both studies as Ruiz-del-arbol, et al.2005[4] included 66 patients, cirrhosis was alcohol related in 35 patients, hepatitis C virus infection related in 25and alcohol plus hepatitis C infection related in 6. Fifteen of the 41 patients with alcoholism were active drinkers at inclusion, most of the patients were admitted to the hospital for the treatment of an episode of tense ascites alone (n=54) or associated with hepatic encephalopathy (n=6). The remaining 6 patients were admitted with ascites and infections (n=4) or gastrointestinal hemorrhage (n=2). 27 patients had hepatorenal syndrome. In contrast, the current study included 100 patients, all patients had HCV-4 related cirrhosis and 40 patients had hepatorenal syndrome. None had gastrointestinal hemorrhage or infection at the time of enrollment in the study. Reduction of cardiac output in patients with HRS was also reported by Ruiz-del-Arbol, et al.2003[13] who studied systemic and hepatic hemodynamics in 23 cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) at infection diagnosis and after SBP resolution. Only eight patients developed HRS. Cardiac output was found to be significantly reduced in patients with HRS. They relayed reduction of cardiac output to SBP only and suggested that cardiac output may decrease in SBP as a consequence of a combination of septic cardiomyopathy and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.In the current study, cardiac output was not high in patients with compensated cirrhosis. This agrees with Alqahtani, et al.2008[14] and Møller and Henriksen. 2006[15] who found that cardiovascular impact was not observed in all patients with liver cirrhosis because in the early stages of compensated cirrhosis the presence of a hyperdynamic circulation is often not apparent but with the progression of the liver disease, there is an overall association between the severity of cirrhosis and the degree of hyperdynamic circulation. In contrast to the previous findings Cardenas and Gines. 2006[16] stated that in the initial stages of cirrhosis (compensated state) in the process of progressive vasodilatation both intravascular volume and cardiac output increase to maintain hemodynamic homeostasis. This contradiction is probably related to the differences in patients’ inclusion and exclusion criteria, etiology of the liver disease and associated co morbidities. Andrés Cárdenas, et al.2000[17] also found that patients with compensated cirrhosis have increased cardiac output and arterial blood pressure within normal limits. In conclusion: Patients with HCV related decompensated liver cirrhosis and HRS have normal or high cardiac output values which seem to be insufficient to maintain adequate tissue perfusion.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML