-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2013; 3(6): 156-165

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20130306.08

The Effects of Family Dentists on Survival in the Urban Community-dwelling Elderly

Rumi Tano 1, 2, Tanji Hoshi 2, Toshihiko Takahashi 2, Naoko Sakurai 3, Yoshinori Fujiwara 4, Naoko Nakayama 2

1Division of Oral Health Sciences, Department of Health Sciences,Saitama Prefectural University School of Health and Social Services

2Tokyo Metropolitan University, Graduate School of Urban Environmental Sciences, Department of Urban System Science

3Graduate school of Medicine, The Jikei University

4Research Team for Social Participation and Health Promotion, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology

Correspondence to: Rumi Tano , Division of Oral Health Sciences, Department of Health Sciences,Saitama Prefectural University School of Health and Social Services.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Objectives Recent reports have shown oral hygiene to be an effective prophylactic for life-threatening systemic diseases, indicating the importance of dental medical support and management provided by family dentists. The present study aimed to clarify the relationship between the presence of a family dentist and survival. Methods A self-administered questionnaire survey was conducted by postal mail on 16,462 community dwelling elderly residents of one city in Japan regarding subject characteristics, presence of a family dentist, and factors potentially determining survival. The initial survey was conducted in 2001 and a follow-up study in 2007 (6 years later) confirmed subjects’ survival status. Chi square test and Kendall’s tau were used to analyze the relationship between each survival factor and the presence of a family dentist and sex for the initial 2001 survey. To analyze survival 6 years later, a Kaplan-Meier survival rate curve was sought and factors determining survival were comprehensively verified by multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazard model. Results A total of 13,066 of the 16,462 responses (collection rate, 79.1%) to the initial survey were analyzed. Presence of a family dentist was reported by 70% of both men and women. With regard to the relationship between each survival factor and presence of a family dentist and sex, no significant difference was observed for number of illnesses under treatment for both men and women and smoking habits in men based on of a family dentist. With regard to other survival factors, significantly better lifestyle status was reported by subjects with a family dentist compared to those without (p<0.001). In the follow-up study 6 years later, the status of 919 subjects could not be confirmed and 1,899 subjects had died. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that regardless of sex, subjects with a family dentist had a significantly higher cumulative survival rate 6 years later than those without (p<0.001). Cox’s regression analysis showed that women with a family dentist had a significantly lower mortality rate 6 years later than women without (hazard ratio, 0.695; 95% confidence interval, 0.56-0.87). Conclusion The present findings demonstrated for the first time that the survival rate was higher for both men and women with a family dentist than those without and suggest that the presence of a family dentist is a significant factor determining survival in women.

Keywords: Family Dentist, Urban Elderly Dwellers, Cumulative Survival Rate, Cox Proportional Hazards Model

Cite this paper: Rumi Tano , Tanji Hoshi , Toshihiko Takahashi , Naoko Sakurai , Yoshinori Fujiwara , Naoko Nakayama , The Effects of Family Dentists on Survival in the Urban Community-dwelling Elderly, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 156-165. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20130306.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In dentistry in Japan, the teeth and oral cavity are generally seen as organs independent of the rest of the body by not only public health, medical and welfare specialists, but also the general public. For example, while regular dental checkups for children are currently based on the maternal and child health and school health systems, from adulthood, they are performed separately from the legally established general health checkups and are left to the discretion of the individual. Dental diseases are also often seen as localized phenomena that occur in the teeth or mouth, as seen from the perception that they are not directly linked to life[1]. Thus, visits to dental hospitals are more common for the purpose of treatment than preventive measures[2], and the low visit rate for regular dental checkups compared with general regular health checkups is an issue. One cause of this is thought to be the history of dentistry to date, which has focused on surgical procedures for restorations and prostheses.In recent years, however, there have been reports showing a relationship between the body in general and the mouth, and the need for comprehensive medical care and support based on collaboration and cooperation between medicine and dentistry has been advocated[3]. In Japan, with its rapidly aging population, attention is being focused on the importance of the teeth and mouth in their contribution to general health as the relationship between dental and systemic diseases has become clear[4,5] and oral care for the elderly has been shown to prevent systemic diseases[6,7]. In 2003, the World Health Organization also warned that oral diseases in elderly people invite decreased physical function and cause decreased quality of life (QOL), and it has raised oral care as an important 21st century public health issue[8]. At the same time, the significance of a regular dentist who provides comprehensive dental health guidance, support, and management is also being debated. From the above, it is conjectured that the effects of having a regular dentist who supports the health of the teeth and mouth may not be limited to the oral cavity, but may also contribute to survival through general health. However, we have found no reports, either from Japan or other countries, that focus on whether individuals have a regular dentist and clarify the relationship of that with survival. Elucidation of the role of dental healthcare in maintaining life will provide scientific evidence that dental healthcare activities contribute to life. Therefore, the demonstration of a relationship between dental healthcare activities and life maintenance is promising for the presentation of measures to prolong life. Such findings will also be useful for the promotion and establishment of support systems by regular dentists.The aim of this study was to show the relationship between survival and whether people have a regular dentist, with urban community-dwelling elderly people as subjects.

2. Methods

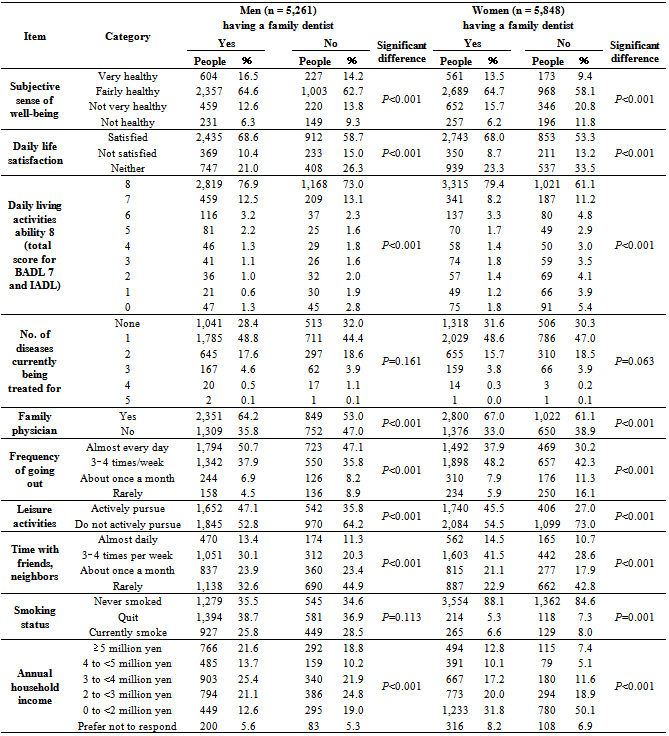

- Of the 17,119 elderly residents aged ≥65 years in a single municipality in Tokyo Prefecture as of September 2001, subjects were 16,462 people remaining after 657 institutionalized residents were excluded. The survey was performed in September 2001 using a self-administered questionnaire that was distributed and collected by mail. Survey items were sex, age, whether the respondent had a regular dentist, QOL indicators, indicators of daily living activities ability, number of diseases under treatment, whether the respondent had a family physician, frequency of going out, leisure activities, time spent with friends and neighbors, smoking habit and total household income (total income of husband and wife) over the past year.In order to determine whether respondents had a family physician and dentist, the question “Do you have a ‘primary doctor[dentist]’ who you see regularly for treatment or to consult about health?” was asked separately for the doctor and dentist. QOL indicators were subjective sense of well-being, which is said to have high predictive validity in estimating survival[9–12], and daily life satisfaction. Subjects were asked the question, “What do you think of your health?” for subjective sense of well-being and “Are you satisfied with your daily life?” for daily life satisfaction.With regard to the daily living activities ability index, Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) were used, in which the reliability of the scale has been confirmed[13], and decreased activity ability has been reported to significantly increase mortality[14–17]. BADL consists of the items “Can use toilet”, “Can take a bath”, and “Can walk when going out”, while IADL consists of the items “Shopping for daily necessities”, “Preparing meals”, “Making bank withdrawals and deposits”, “Completing pension and insurance forms”, and “Can read newspapers and books”. Each item was scored with the options “Can do = 1” and “Cannot do = 0”, and was calculated with a maximum total score of 8 and minimal total score of 0 for both the BADL and IADL.For diseases currently under treatment, the total number of diseases was counted from the response options for hypertension, stroke, diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, other and none (multiple responses allowed). For items related to activities of daily living, questions on “Frequency of going out”, “Positive attitude toward leisure activities”, and “Frequency of spending time with friends and neighbors” were asked, which have been shown to affect life prognosis [18]. The questionnaire also asked about smoking status, which has been shown to be strongly related to death[19–21]. The response options for questions on the questionnaire are shown in Table 1. In performing the analysis, age was divided into 5-year groups based on responses. The options for annual household income were none, less than one million yen, one million to less than two million yen, two million to less than three million yen, three million to less than four million yen, four million to less than five million yen, five million to less than seven million yen, seven million to less than eight million yen, eight million to less than nine million yen, nine million to less than ten million yen, and ten million yen or more. These responses were reclassified as shown in Table 1. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows, with 5% taken as the level of statistical significance.The survey of September 2001 was used as baseline data, with a follow-up performed five years and 11 months later, until August 2007. Survival status during those six years of data was examined with linkage based on ID management, performed with the cooperation of the city government. In the analysis, χ2 test and Kendall’s tau test were used for relationships with each item in two groups of subjects, those with and without a regular dentist in 2001. Analysis of survival after six years was performed with a log-rank test using the Kaplan-Meier method. A Cox regression analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model after dividing each variable into subject and reference groups was also performed as a comprehensive test of whether the measured variables could be predictors of survival.This study was approved by the ethics committees of the Graduate School of Urban Science, Tokyo Metropolitan University, and the Department of Urban System Science, Tokyo Metropolitan University. A letter of agreement was concluded between the city and university for the protection of privacy and obligation to maintain confidentiality.

3. Results

- In the 2001 survey, responses were received from 13,195 people (including proxy responses by a family member), for a response rate of 80.2%. One hundred and twenty-nine people were excluded because of missing responses, leaving 13,066 as the total number of subjects for the analysis, including 6,012 men (46.0%) and 7,054 women (54.0%).

3.1. Relationship of Lifestyle Factors in People with and without a Family Dentist and in Men and Women

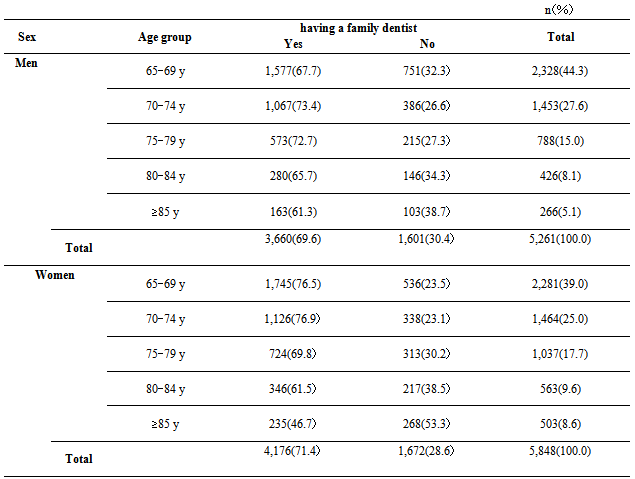

- The number of people with family dentists was 7,836 (60.0%) overall and the number without a family dentist was 3,273 (25.0%). It was unknown in 1,958 (15.0%). By sex, the number with family dentists was 3,660 men (69.6%) and 4,176 women (71.4%). The proportion was about 70% in both men and women (Table 2).

|

|

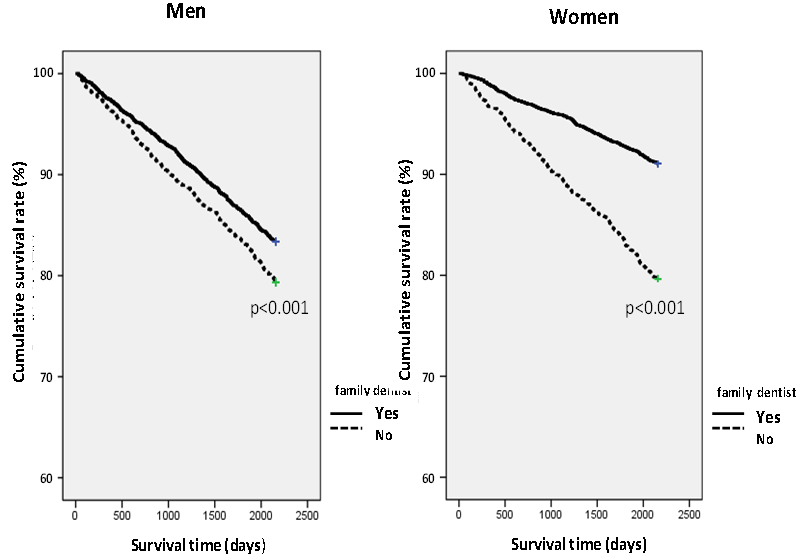

| Figure 1. Cumulative survival rates in subjects with and without a family dentist |

3.2. Cumulative Survival rate in People with and without a Family Dentist

- In the follow-up survey, after six years based on the 2001 data, 919 subjects had moved out of the city and 1,899 were confirmed to have died. Therefore, the total number of subjects for the 2007 analysis was 12,147 people, including 5,665 men (46.6%) and 6,482 women (53.4%).A survival analysis of the cumulative survival rate over the six years was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method using a log-rank test for subjects with and without a family dentist and for men and women. The results showed that cumulative survival rate was significantly higher in those with a family dentist than in those without a family dentist in both men and women. The cumulative survival rate after six years in the groups with a family dentist was 83.4% in men and 91.0% in women, as compared with 79.3% of men and 79.7% of women without a family dentist. Thus, the cumulative survival rate was higher, particularly in the group of women with a family dentist, as compared to those without a family dentist, and in groups without a family dentist, the decrease in the cumulative survival rate showed a very similar survival curve for both men and women (Fig. 1).

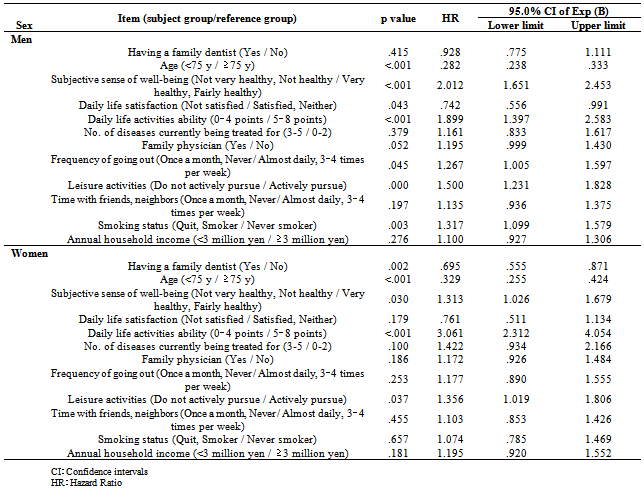

3.3. Comprehensive Analysis of Lifestyle Factors that Affect Mortality Rate in Men and Women

- As a comprehensive analysis, including lifestyle, of effects on survival with and without a family dentist, an analysis was conducted using a Cox proportional hazards model. The results showed that in men, although the group with a family dentist had a lower hazard proportion after six years than the group without a family dentist, the difference was not significant (HR: 0.928, 95% CI: 0.78–1.11). In women, however, the hazard ratio was significantly lower in the group with a family dentist than in those without (HR: 0.695, 95% CI: 0.56–0.87).

|

4. Discussion

- A family dentist is defined as “a dentist who provides health, medical and welfare care related to the mouth and teeth through the patient’s life cycle, and can fulfill several necessary community-based roles”[22]. In the present questionnaire survey the respondents were asked whether they had a primary dentist who they could visit for regular treatment and to consult about health. Therefore, among the roles of family dentists proposed by dental healthcare providers, a family dentist is mainly perceived as being someone who provides necessary dental care to community residents and dental health consultations according to the needs of community residents. At the same time, however, reports on the functions of family dentists indicate that there are differences in perception between community residents and dental healthcare providers[23,24]. Discussion of the roles of family dentists has also heightened with the establishment in 2000 of initial and return visit fees for family dentists in the health insurance remuneration for medical services, and in recent years, attention has been directed to the significance of having a family dentist[25].

4.1. Effect on Survival Time of Having/not Having a Family Dentist and Lifestyle Factors

- The results of a comprehensive analysis of survival time and whether a person has a family dentist in this study, using a Cox proportional hazards model, showed longer survival times in both men and women for those with a family dentist than in those without a family dentist. However, a significant correlation was demonstrated between survival time and whether a person had a family dentist in women only.It was originally thought that dental prostheses to support eating were an important factor in the reason for the positive effects of a family dentist on life prognosis in both men and women. Many elderly people require treatment with dental prostheses, and their relationship with life prognosis has been investigated as a direct effect on eating and nutritional intake[26,27]. In other words, it was thought that people with a family dentist obtained desirable living habits based mainly on dietary lifestyle through the dental health behavior of seeking dental treatment. Having a family dentist was also suggested to be related to positive health behaviors in which mental, physical and social factors contribute to significantly preserve life.Next, with regard to the finding that a family dentist was significant as an independent factor in women only, it was reported that dental care facilities are switching to a more prevention-centered approach in recent years, and that in women, there has been a shift to emphasis on prevention with the aim of receiving dental treatment[28]. That report showed a clear difference between men and women in the type of dental treatment received, which was not seen in a 1999 survey on health and welfare trends. Thus, it is possible that the greater frequency with which women receive support for dental care and health by family dentists affects life prognosis. Moreover, in this survey, women with low daily living activities ability were shown to have a mortality rate about three times higher than that of women with high ability. Decreased life activities ability is likely to lead to difficulty in performing the oral health behaviors of receiving dental treatment and cleaning the mouth. This suggests that one role that should be performed by family dentists is active provision or support for elderly women so that they can receive treatment, or providing visiting dental care for elderly women with decreased living functions, which may contribute to the life prognosis of elderly women.

4.2. Relationship between Having/not Having a Family Dentist and Lifestyle Factors

- To date, studies have focused mainly on the relationship between the oral cavity and whether a person has a family dentist. Many reports have shown that people with a family dentist have better oral health status and oral health behaviors[29-31]. However, there have been few reports looking at the status of the relationship of lifestyle factors in people with a family dentist in which the subjects were community-dwelling elderly living in a city. In this study, 70% of both men and women had a family dentist. The percentage of people with family dentists was 60% in a survey of adult community residents[32] and among the results of surveys conducted in Tokyo Prefecture the percentage was 70% in municipalities similar to that in the present study[33]. Thus, the present survey results do not differ greatly from other studies. Subjective sense of well-being and daily life satisfaction were both significantly higher in people with a family dentist. Eating is one of the pleasures of elderly people[34,35] and decreased chewing ability has been shown to be a factor in a feeling of poor health[36]. This also indicates the possibility that the teeth and oral cavity, which serve major roles in the series of actions of ingesting, chewing, and swallowing that are related to eating, serve an important role in maintaining and improving QOL. The significantly higher living activities ability in the group with a family dentist is supported by results of previous studies[37,38] indicating that oral status is closely involved with physical functions. The percentage of subjects currently being treated for disease was not significantly different between groups with and without a family dentist in either men or women. The answer options in this survey were for typical diseases, and “Other” was included, so it is possible that many respondents had some kind of disease regardless of whether they had a family dentist.No significant differences in smoking habit were seen in respondents with or without a family dentist among men only, which agreed with a previous study[29]. Smoking has been shown to be related not only to systemic diseases but also to the dental diseases of periodontal disease and oral cancer[39,40]. In the future, it may be necessary to actively promote efforts by family dentists to support smoking cessation in order to maintain or improve oral and general health.A relationship between economic factors and regular dental checkups was previously demonstrated[41], and it is reported that financial difficulties limit dental hospital examinations in elderly people in particular[42]. According to a dental treatment white paper, the cost of dental treatment increases according to income, and people in households with the highest income pay 2.5 times more for dental treatment than people in households with the lowest incomes. In other countries, low income households also have a lower rate of dental examinations[43] and low income has been shown to be related to decreased chewing ability[44]. In the present survey, those with higher income had family dentists, which supports these earlier studies. Having a family dentist is significantly related to lifestyle factors that may dictate survival, and there is a need to investigate a dental insurance system that will allow elderly people to receive the dental treatment and care they need.

4.3. Cumulative Survival Rates for People with and Without a Family Dentist

- According to vital statistics (2010) of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the leading cause of death in Japan is malignant neoplasm, with heart disease second, cerebrovascular disease third, and pneumonia fourth. In 2010, these four diseases accounted for 70% of all deaths. Among malignant neoplasms, oral cancer, which is a malignant tumor that occurs in the oral region, is said to account for 1–2% of all cancer in Japan and to be somewhat more frequent in men[45]. The incidence of oral cancer is reported to be about 3% of all cancers in the USA[46,47], Canada[48] and Germany[49]. The incidence rate among all cancers is thus low internationally. However, it may be concluded from the many epidemiological studies that have examined the relationship between oral cancer, survival duration, survival rate and life prognosis that there is a close relationship between oral cancer and survival[50–53]. Oral cancer is asymptomatic in the precancerous stage and although the 5-year survival rate is higher than 90% with early detection[54], 60% of cases are discovered in the advanced stage[55]. The significance of early detection in the precancerous stage by a dentist has been indicated[56]. As society ages, the importance of early detection and treatment of oral cancer in elderly people[57] in particular has been emphasized. Thus, early detection of oral cancer by a family dentist serves an important role in improving survival rate.Recent research has shown that heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, the major causes of death after malignant neoplasms, are correlated with periodontal disease[58,59]. According to the 2005 Survey of Dental Diseases, about 80% of adults in Japan have established oral infections. Periodontal pathogens first occur in the gingival sulcus, and with persistent infection the gingival tissue breaks down and at the same time bacteria invade into capillaries of the gingival epithelial attachment and circulate to the entire body. Thus, the periodontal pathogens that cause chronic infections place a burden on organs and tissues of the entire body via the blood, suggesting an effect on heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. The detection of periodontal pathogens in coronary artery disease[60], the relationship between poor oral status and cardiovascular mortality rate[61], and the involvement of poor oral hygiene with pneumonia[62] have been reported, thus supporting the position that periodontal disease is involved in heart disease. Therefore, on the grounds that intraoral bacteria are associated with the blood circulation system, treatment and prevention of periodontal disease by family dentists may contribute to prevention of systemic diseases.There are accumulating results from clinical studies showing that prevention of aspiration pneumonia, which occurs when foreign matter is aspirated into the lungs [63–66]. Aspiration is particularly common in elderly people, in whom decreased physiological and reflex functions related to swallowing and respiration are seen, and in people with cerebrovascular disorders. Pneumonia caused by the aspiration of oral bacteria into the lungs is therefore a problem. Oral care consists of organic oral care performed by the individual (including his or her family members or caregiver) and professionals for the purpose of oral hygiene, and functional oral care with the purpose of maintaining or improving oral function. Oral care support by a family dentist reduces the number of bacteria in the oral cavity and pharynx[67] and may help to prevent pneumonia by bringing about improved oral function related to swallowing.Family dentists serve to diagnose dental disease and contribute to the control of oral bacteria, suggesting that the survival rates of groups with family dentists would be increased. To extend healthy lifespan in the future, a medical system with coordination between doctors and dentists is desired, and interactions from the perspective of mutual involvement with life are thought to be necessary.

4.4. Issues for Future Study

- This study was a large-scale survey of all community-dwelling elderly people in one city. Random error was minimized by the high response rate and the study results may be considered to have high internal validity. However, a random sampling survey in another community to raise the external validity, comparative investigations by country to maintain the universality of the study results, and more comprehensive and expanded studies are warranted [68,69]. In addition, as there have been no similar reports internationally, reproducibility from follow-up is needed for the findings obtained from this study.A limitation of this study is that it was not an empirical study with interventions that examined the oral cavity, including the condition of the oral cavity, oral hygiene status and oral function tests of subjects. In addition, subjects were not asked the purpose of visits to their family dentist, type of treatment or type of support from their dentist and dental hygienist. Therefore, together with examinations of the oral cavity, a survival follow-up study after determining the purpose for visiting the family dentist and the specific content of self-care and professional care for the teeth and oral cavity are issues for the future. In doing so, an exploration of the real clinical signs and obtaining correlative data between the prophylactic action or oral therapeutics and the stage of systemic compensation or decompensation to allow a real quantification of the role of a family dentist is warranted.This study was only an attempt to describe the relationship between having or not having a family dentist, and cumulative survival rate and survival time from a follow-up study. To verify the functions of family dentists, a survey with questions that enable the functions of family dentists to be understood quantitatively will be necessary in the future. Subsequently, clarification of the causal relationship between having a family dentist and physical, mental and social factors that dictate health is necessary. In addition, from the perspective of healthy lifespan, which is emphasized in Japan with its aging population, an exploration of the relationship with care prevention focused on preventive dentistry is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Funding for this study was provided primarily by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (1989–1991: H10-Ken-042), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (1993–1995 No. 1531012), and Tokyo Metropolitan University 2001-2002, Tokyo Metropolitan University Center for Urban Studies joint research, “Research on Urban Development for Safety and Health”. This study was also funded by “A 2006–2007 Tokyo Metropolitan University research grant” and subsidized by the Mitsubishi Foundation (2009-21), the Okawa Foundation, and the International Garden and Greenery Exposition (09RD-16).We are grateful to all the city residents who participated in this study. We would also like to give special thanks to Tama City for its systematic support in the ongoing implementation of this large-scale study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML