-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2013; 3(6): 121-125

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20130306.01

Serological Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis among Pregnant Women in Khartoum State

Eltayib Hassan Ahmad-Abakur, Mohammed Omer Ali Abdalla, Mohammed Ahmed I Huli, Tarig Mohammed Saad Alnour

Dept. of Microbiology & Immunology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, AlzaiemAlazhari University, P.O. Box 1432, Khartoum Bahri 13311, Sudan

Correspondence to: Eltayib Hassan Ahmad-Abakur, Dept. of Microbiology & Immunology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, AlzaiemAlazhari University, P.O. Box 1432, Khartoum Bahri 13311, Sudan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Objective: C.trachomatis infection influences the pregnancy outcomes leading to premature rupture of membranes, prematurity, low birth weight and prenatal mortality. Thepresent study was carried out in Khartoum Educational Hospital and it was aimed to detect the Chlamydia trachomatis and its reproductive factors among Sudanese pregnant. Material and methods: 92 blood samples were collected from pregnant women aged from 17 to 42 years old. The separated sera were subjected to anti-Chlamydia trachomatis (IgG) and anti- Chlamydia trachomatis(IgA) using ELISAtechniques. Questionnaire survey was conducted to collectthe information related to the study such as age, gravidity, education level, history of previous abortion and past genital tract infection.Results: thirteen serum samples (14.1%) were sero-positive for anti-chlamydial IgG and 5 samples (5.4%) were reactive against anti-chlamydial IgA. Statistically, there was no significant relationship between the presences of immunoglobulin IgG or IgA of Chlamydia trachomatis and age of pregnant woman with P value 0.641 and P 0.803 respectively. Most of participated pregnant women completed their primary 33(35.9%) or secondary 36 (39.1%) school education, although there was no relation between Chlamydia trachomatisinfection and the education level {(P=0.562 for IgG) and (P=0.930 for IgA}. The results revealed statistically a significant relationship between immunoglobulin IgG and previous abortion with P value 0.016 whereas the presence of IgA showed insignificant relations with the previous abortion (P=0.325). The gravidity and past genital tract infection did not affected the Chlamydia trachomatis infection{(P=0.99 and P=0.617 for IgG respectively) and (P=0.261 and 0.717 for IgA respectively}. Conclusions: the present study revealed significant relation between C. trachomatis IgG antibody and previous abortion.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Gravidity, Previous Abortion and Past Genital tract Infection

Cite this paper: Eltayib Hassan Ahmad-Abakur, Mohammed Omer Ali Abdalla, Mohammed Ahmed I Huli, Tarig Mohammed Saad Alnour, Serological Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis among Pregnant Women in Khartoum State, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 121-125. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20130306.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The global annual incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), excluding HIV and viral hepatitis is 333 million cases, of which Chlamydia infections represent 89 million cases“more than 26 %”[1].There are at least 18 serovars of C.trachomatis; the medical important serovars associated with endemic trachoma are A, B, Ba, and C while D-K serovars are associated with sexually transmitted disease and that cause lymphogranuloma venereum are L1, L2, and L3[2]. Genital infection with C. trachomatis is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with most women being unaware that they are infected[3], the amount of costs related treatment of chlamydial infection complications considered costly second only to HIV[3].In women, C.trachomatis causes non-specific urethritis, cervicitis, endometritis and salpingitis. Infection is confined to epithelial surfaces but an immune-mediated host response can cause severe inflammations to the tissues, especially after repeated episodes. The most serious complication Chlamydial upper genital tract infections in women are infertility and ectopic pregnancy which result from damage to the fallopian tubes[4], repeated or chronic chlamydial infection can cause severe immunologically- mediated chronic inflammation, which is the basis of the disease such as blinding trachoma and chronic salpingitis causing infertility. Typically there an exaggerated inflammatory response but Chlamydiae could be isolated in very small numbers. In contrast asymptomatic genital infection may be associated with prolonged shedding of large numbers of Chlamydiae with minimal inflammatory response[4]. However, C.trachomatis infection influences the pregnancy outcomes leading to premature rupture of membranes, prematurity, low birth weight and prenatal mortality[5,6]. The prevalence of C. trachomatis among pregnant women were (25.7%) in Brazil[7], 19% in India[8], 10.5% in Saudi Arabia[9], 9% in Kenya[10], and 4.8% in Newzland[11].Most of the Chlamydia infections are difficult to diagnose by clinical examination alone and in many developing countries are usually treated by empirical treatment which affects the health and economic status of the mother[3]. Antibody tests are useful in sero-epidemiological studies of C.trachomatis infection[12]. The reference method for detection of C. trachomatis infection has been by growth of the organism in tissue culture using McCoy cells. Cell culture, however, is not routinely employed for screening large numbers of patients[13]. Several studies have suggested that elevated titres of IgG and IgA antibodies may be markers of active infection. Recently, an indirect immuno-peroxidase assay capable of detecting specific IgG and IgA antibodies to C. tracomatis in human serum was developed[14, 15, 16, 17].It is well stated that the sexually transmitted infections (STI) are a major public health problem in most African countries on account of their associated morbidity and mortality[18]. Moreover; theasymptomatic nature of some STI among pregnant women and absence of authentic documentation system vague the real situation of these diseases, therefore thepresent study was carried out to detect the Chlamydia trachomatis and its reproductive factors among Sudanese pregnant women in Khartoum state.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Area and Population

- The present study was facility based case- study. Sudanese pregnant women whose attended Khartoum Educational Hospital “Khartoum state, Sudan” during the period from Mayto August 2012 and had notbeen diagnosed previously for having C.trachomatis infection were considered eligible to enrol in this study. Ninety-two candidates were agreed to participate in this study.

2.2. Data Collection

- Data related to study such as age, number of pregnancy times (gravidity), education level, previous abortion and past genital tract infection were collected using direct interview technique.

2.3. Sample Collectionand Processing

- Sterile disposable vacutainer tube was used to collect 5 ml of blood from the antecubital vein under aseptic conditions, the blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature. The clotted samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes in order to separate the sera; the obtained sera were frozen at -20ºC until used. The separated sera were subjected toanti- Chlamydia trachomatis(IgG) and anti- Chlamydia trachomatis (IgA) using ELISA techniques.

2.4. Principle and Procedure of ELISA Test

- The ELISA test provides a semi-quantitative in vitro assay for human antibodies of the class IgG or IgA against Chlamydia trachomatis in serum or plasma. The test kit contains microtitrestrips each with 8-break- off reagent wells coated with Chlamydia trachomatis antigens. The first reaction step, diluted patient samples were incubated in the wells. In the case of positive sample specific IgG or IgA antibodies bound to the antigens. To detect the bound antibodies, a second incubation was carried out using an enzyme –labelled anti-human IgG or IgA (enzyme conjugate) catalysing a colour reaction[19, 20].The test was done according to the manufacture structure (Euroimmun), briefly: - Serum sample was diluted 1: 101. - 100µl from each of calibrators, positivecontrol, negative controlanddiluted samples was transferred into proper microtitrewells, and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, they washed three times using 300 µl of working wash buffer for each wash. - 100µl of the enzyme conjugate was added into each of the microplate wells and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, then after washed as described above. - 100µl of chromogenic/ substrate solution was added into each of the microplate wells, and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. - 100µl of the stop solution was pipetted into each of the microplate wells to terminate the reaction.- Finally the colour intensity was measured at a wavelength 450 nm.

2.5. Calculation and Interpretation of ELISA Results

- The results were evaluated semi-quantitatively by calculation a ratio of the extinction according to the following equation:Extinction of the control or sample /Extinction of the calibrator =RatioThe results interpreted as follows: Ratio < 0.8 considered as negative result.Ratio ≥ 1.1 considered as positive result.

2.6. Data Analysis

- Data were processed and analysed using Excel – master sheet and statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) namely Chi square test.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

- The ethical consideration of this study was approved by the ethics committee, faculty of graduate studies, Alzaeim Alazhari University, Sudan. Privacy and confidentiality of participants were ensured.

3. Results

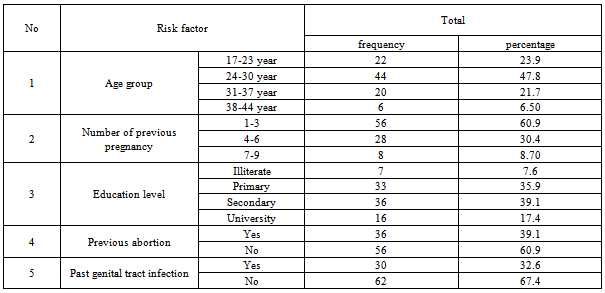

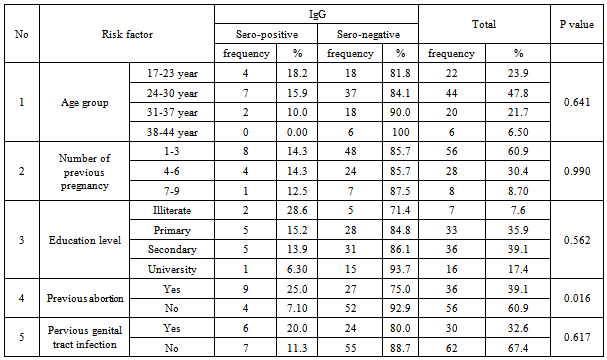

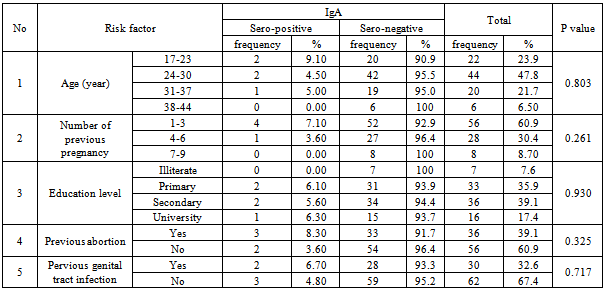

- A total of 92 pregnant women were included in this study, their age ranged from 17-42 years, the most frequent age group was 24-30 years 44 (47.8 %), the illiterate participants were only 7(7.6%) and the number of pregnancy times varied from 1-9while the previous abortion was 39(39.1%) as shown in table 1.Thirteen serum samples (14.1%) were sero-positive for anti-chlamydial IgG and 5 samples (5.4%) were reactive for anti-chlamydial IgA.Statistically, there was no significant relationship between the presence of immunoglobulin IgG or IgA of Chlamydia trachomatis and age of pregnant woman with P value 0.641(table 2) and P0.803(table 3) respectively.Most of participated pregnant women completed their primary 33(35.9%) or secondary 36(39.1%) school education (table 1), although there was no relation between Chlamydia trachomatis infection and the education level {(P=0.562 for IgG(table 2)) - and (P=0.930 for IgA(table 3)}. The results revealed statistically a significant relationship between immunoglobulin IgG and previous abortion with P value 0.016 (Table 2) whereas the presence of IgA showed insignificant relations with the previous abortion (P=0.325) (Table 3). The gravidity (number of pregnancy times) and previous genital tract infection did not affected the Chlamydia trachomatis infection{(P=0.99 and P=0.617 for IgG respectively) and (P=0.261 and 0.717 for IgA respectively) (Table2 and 3)}.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The increasing numbers of chlamydial infections in Sub- Saharan Africa is related to the fact that these infections frequently cause asymptomatic or silent disease and do not motivate patients to seek medical care, resulting in extended period of infectivity and high risk of developing complications. The technique applied in this study (ELISA) was the most reliable and common method used in diagnosis of C. trachomatis. Contrary to the ordinary immunological principle where IgM is used to detect current infection, in this study IgA was used to detect the recent infection. Multi studies suggested that the presence of serum IgA may be a useful marker for activeC. trachomatis infection[16, 17, 21]. However, the present study showed that C. trachomatis antibodies IgG and IgA were 14.1%, 5.4% among Sudanese pregnant women respectively. These findings were relatively near to that reported in Kenya(9%)[10] and Saudi Arabia (10.5 %)[9] and greatly less than that reported in Brazil(25.7%)[7].Our findings indicated that C. trachomatis infections common among age group (24-30 year), this result was in alignment with Ingrid et al.,[23] results whose stated that C. trachomatis infections common among pregnant women less than 30 and Mascellino et al.,[16] whose reported more than 25 year as suspected age group and contrary to that reported for pregnant women in Saudi Arabia where it was common above 34 years[9]. However, Kusano et al.,[24] mentioned that junior school graduates had the highest frequency of positive cases, followed by graduates of high schools, vocational schools junior colleges, and university graduates had the lowest frequency.In the present study the presence of C. trachomatis antibodies IgG or IgA was not affected by educationlevel, past genital tract infection and number of pregnancies. Published data concerning gravidity were diverse; some studies demonstrated a higher rate of infection among multigravida compared to primigravida[25, 26] whereas the other showed that the prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was significantly higher among women with no history of delivery[27]. However, contrary to our findings Kusano et al,[24] (in study carried out in Japan) showed that short duration of education and past history of sexual transmitted infections was associated with a significant seropositive. These different might be referred to socio-cultural factors as our communities had suspicious about STI and the limited awareness among participants concerning the disease.The present study showed significant relation just between C. trachomatis IgG antibody and previous abortion of pregnant women. Several studies documented that the history of previous abortions suggests a higher risk forC. Trachomatis infection[8, 24, 28].

5. Conclusions

- The present study revealed significant relation between C. trachomatis IgG antibody and previous abortion. Thus pregnant women should be definitely tested for chlamydia infection. Moreover, health education and awareness on the disease and its transmission to women of reproductive age group in general and pregnant women in particular should be created during antenatal follow up to reduce the risk of C. trachomatis infection in pregnant women.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML