-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2013; 3(4): 68-73

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20130304.03

Indeterminate Form of Chagas’ Disease and Metabolic Syndrome: A Dangerous Combination

Elaine Cristina Navarro1, Mariana Miziara de Abreu1, Francilene Capel Tavares1, José Eduardo Corrente2, Camila Maria de Arruda1, Paulo Câmara Marques Pereira1

1Botucatu Medical School, UNESP , Department of Tropical Disease

2Bioscience Institute, UNESP, Department of Biostatistics

Correspondence to: Paulo Câmara Marques Pereira, Botucatu Medical School, UNESP , Department of Tropical Disease.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Chagas’ disease (CD) has been a major concern in public health in Latin America countries and in Brazil there are about 3 million people suffering from this disease. With the social and economic changes which have been occurring in the last 6 decades in the country, there have been a lot of changes in the population life style with severe metabolic consequences, especially for those with Chagas' disease. The objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with the indeterminate form of CD. A total of 74 individuals, mean age of 55.6 years, participated in the study. Anthropometric and biochemical evaluations were performed. Overweight/obesity was found in 86.5 % of individuals, increased waist circumference in 72.5%, and 67% had more than 30% of fat mass. Hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia were observed in 24.3% and 75.7% of patients, respectively. Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed in 48.2% of patients. The family history revealed high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (80.3%), systemic arterial hypertension (57.1%) and diabetes mellitus (42.8%). A total of 90% of patients were overweight/obese, and it is well known that increased adipose tissue, specially visceral adipose tissue is highly associated with dyslipidemia and cardiovascular diseases, as well as imbalance in production of proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines produced by that tissue. Adipocytes are also known as a reservoir for Trypanosoma cruzi, favoring an increase in parasite load and a possible reacutization of the disease. Therefore, the study individuals are at high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases as well as further symptomatic form of the Chagas' disease, mainlychagastic cardiopathy.

Keywords: Indeterminate Form of Chagas’ Disease, Metabolic Syndrome, Visceral Fat, Cytokines

Cite this paper: Elaine Cristina Navarro, Mariana Miziara de Abreu, Francilene Capel Tavares, José Eduardo Corrente, Camila Maria de Arruda, Paulo Câmara Marques Pereira, Indeterminate Form of Chagas’ Disease and Metabolic Syndrome: A Dangerous Combination, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 68-73. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20130304.03.

1. Introduction

- Chagas' disease (CD) also known as American Trypanosomiasis was first described in 1909 by the brazilian physician Carlos Justiniano Chagas. The disease is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi and affects 8 to 10 million people worldwide. Its incidence is estimated as 40 thousand new cases a year[1].The most common transmission is vector-borne. T. cruzi infection maybe also transmitted to humans congenitally, by blood transfusion and organ transplant and by oral route[2,3].According to Petherick (2010), there are at least 3 million infected people in Brazil, and as most chronic chagasic individuals have the indeterminate form of the disease (no symptoms) these figures may be even higher[2].The indeterminate form of CD affects about 60% of chronic patients. The form chronic symptomatic affect 40% in which have digestive, cardiac or mixed form.The digestive form causing megadiseasesof the esophagus (dysphagia, feeling of fullness aftereating or drinking, chest pain and regurgitation, and aspiration is a commoncomplication in advanced cases) and colon (chronicconstipation and abdominal pain, volvulus, obstruction and perforation of the bowel may occur).Cardiac formleads to abnormalities in the conductive system and the most common manifestation are palpitation, arrhithimias, including ventricular extrasystoles, boutstachycardiac, and various digrees of heart block. The advanced station have cadiomegaly, failure heart and may occur sudden death.Chagasic cardiopathy has had a huge impact on brazilian public health because of the large number of individuals at productive age (30 to 50 years old) who present the severe forms of the disease, leading to early disability and retirement[3,4]. The association between CD and metabolic abnormalities has been studied in symptomatic individuals with cardiac and mixed forms. However, no studies have been reported concerning the relationship between those abnormalities and the indeterminate form of CD.The diagnostic methods for acute Chagas’ disease include direct microscopic examination of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat preparation for motile trypanosomes. The most sensitive technique is xenodiagnostic. The diagnosis of chronic form requires demonstration of antibodies to T. cruzi.Botucatu Medical School (FMB/Unesp), Brazil, has a specialized out-patient ward to treat nutritional and metabolic disorders in patients with tropical diseases. In this service, 400 patients with CD have been periodically followed-up. In a previous study by Geraix et al., (2007), more than 70% of patients had the indeterminate form of the disease, and although no tissue impairment was observed, as a result of the combined action from the presence of protozoan and pro-inflammatory cytokines of the immunological system, they had several biochemical changes which predisposed them to develop metabolic syndrome[5]. In 2001, the National Cholesterol Education Program – Adult Pannel III (NCEP-ATPIII) defined metabolicsyndrome by the presence of visceral obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, reduction in HDL-cholesterol, hyperglycemia and arterial hypertension. The presence of three of these factors classifies the subject as a carrier of this syndrome[7,8,9]. Many studies corroborate that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is age dependent and it may affect 40 to 50% of the population over 60 years[10,11]. The majority of the chagasic population in Brazil is over 40 years, and due to effective eradication programs against the disease, the number of young individuals are fewer and fewer, particularly in Sao Paulo State[12].Using this approach and taking into account that the metabolic syndrome is an important threat to public health, its association with CD should be better investigated. Its importance is based on the fact that the individuals are at 5 to 10 fold increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus type 2, and 2 to 3 fold increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease[13].The objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with the indeterminate form of CD.

2. Methods

- This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Botucatu Medical School (Protocol number 3600-2010). The inclusion criterion was the presence of two positive serological tests for Chagas' disease (ELISA and hemagglutination or indirect immnunofluorescence tests), electrocardiogram, opaque enema and normal esophagus- stomach - duodenum and lack of clinical symptoms. The exclusion criterion was the presence of chronic renal diseases, nephrotic syndrome and hypothyroidism. Patients in the study were adults from both sexes and were being cared for in the Nutrition Ward in the Tropical Disease Department of the Botucatu Medical School.Anthropometric and biochemical (lipid and glycemic profile) evaluations were performed and the criteria were based on those established by the National Cholesterol Education Program - Adult Treatment Panel III(NCEP-ATPIII) as follows: Waist circumference (WC) < 88 cm for women and < 102 cm for men, glycemia ≤ 100 mg/dL; total cholesterol ≤200 mg/dL; triglyceride ≤150 mg/dL and HDL- cholesterol ≥ 50 mg/dL for women, ≥ 40 mg/dL for men and systolic and the diastolic pressure values ≤ 130mmHg or ≤ 85mmHg. Body mass was measured by 2 different methods: Body mass index (BMI) and percentage of fat mass using the bioimpedance analysis (BIA).Evaluation of nutritional status and body composition was based on the following body measurements: Weight (kg) was obtained using anthropometric digital platform scale, 0.1 kg accuracy, barefoot individuals stepped on it wearing bare minimum clothes; height (m) was obtained using the adjustable measuring rod of the anthropometric scale, 0.5 cm accuracy; body mass index (BMI) was determined dividing weight by square height; waist circumference (WC) was measured using a tape measure firmly applied to the maximum anterior protuberance at the umbilical scarf, and bioimpedance (BI) was obtained using the BIA-101 Q analyzer (RJL Systems Inc, Detroit, MI) device to evaluate the percentage of fat mass[14,15].Metabolic (lipid and glycemic) profile was evaluated by determining serum levels of glucose using the Johnson & Johnson 750 kit (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics), and total and fractions of cholesterol as well triglycerides using the Johnson & Johnson kit (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics). Dry chemistry with Vitros 750 auto-analyzer was used in both methodologies.All patients were taken 10 ml blood samples after 12-hour fasting. They were advised not to consume alcoholic beverages neither to do physical exercises in the previous day.To evaluate the impact of dyslipidemia, patients were allocated into 2 groups: G1 – no dyslipidemia and G2 – with dyslipidemia. Statistical analysisInitially, descriptive measurements as frequency and percentage were obtained for qualitative variables, and mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables. Chi-Square test was used to evaluate association among qualitative variables. Student’s T-test was used to compare quantitative variables.Considering group 2, the factors that affect the occurrence of metabolic syndrome were obtained using an adjusted Logistic Regression model, in which, occurrence of metabolic syndrome was the response variable and the other ones (sex, age, etc) were explanatory variables.The significance level was 5% or p- corresponding value for all tests. All analyses were performed using the SAS program for Windows, v.9.2.

3. Results

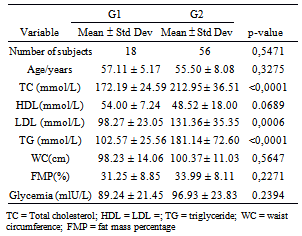

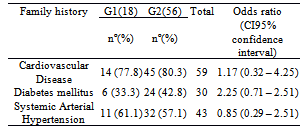

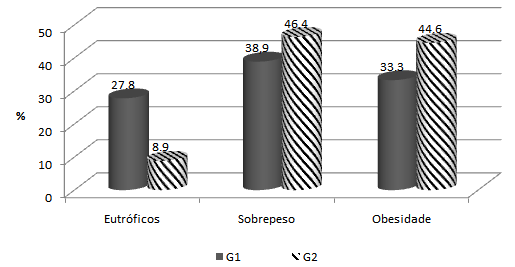

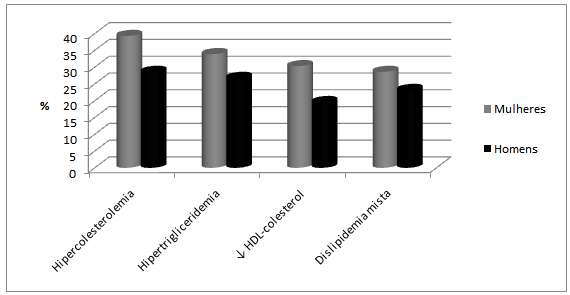

- A total of 74 individuals participated in the study, 41 of them were women (55.4%), and 33 were men (44,6%) aged from 40 to 78 years. Mean age was 56.4 years (SD = 8.2 years) and 55.3 years (SD = 6.6 years) for women and men, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found between age of men and women (p=0.5471).Anthropometric evaluation revealed that 86.5 % of the individuals were overweight or obese (figure 1), 72.5% of them had increased waist circumference and 67.1% of them had more than 30% fat mass.The population was allocated into 2 groups: G1 (no dyslipidemia) and G2 (with dyslipidemia). A total of 18 (24.3 %) individuals were in G1, 7 of them were women and 11 were men; 56 individuals (75.7%) were in G2, 34 of them were women and 22 were men. No statistically significant difference was found between sex and group (p=0.1051). Mean age of individuals from G1 was 57.1 years (± 5.2 years) and from G2 was 55.5 years (±e 8.1 years). No statistically significant difference was found between them (p=0.3275). No significant association was found in total cholesterol (TC), HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride (TG) between sexes for group 2 (table 1). Among individuals of group 2,hypercholesterolemia was the most frequent dyslipidemia in both sexes followed by hypertriglyceridemia (Figure 2). No positive association was found between groups (G1 and G2) concerning BMI (p=0.1243) and fat mass percentage (p=0.5316), but a significant association (p=0.0379) was found concerning waist circumference (WC).Hyperglycemia was observed in 18 individuals (24.3%), 3 of them in G1 and 15 (26.7%) in G2.

| Figure 1. Nutritional classification according to BMI of individuals in G1 (no dyslipidemia) and G2 (with dyslipidemia) |

| Figure 2. Classification according to the dyslipidemia presented by individuals of G2 separated by sex |

|

|

4. Discussion

- CD affects about 3 million Brazilian people nowadays, and because of efficient measures taken for its control, these people are aged more than 40 years. The individuals who participated in this study are more than 40 years, and are withinthe group of people who, even having the parasite, are economically active. Therefore, the development of the disease has a great impact on individuals with the disease and on the government concerning both expenses with treatment of symptomatic individuals and social security system which is overwhelmed by early retirements. According to Alves et al. (2009), there is a direct association between age and coexistence of chronic diseases in elderly patients with CD, such as arterial hypertension (56.7%) and dyslipidemia (20%)[16]. In this study, the prevalence of systemic arterial hypertension was 43.2%, but if individuals at 60 years or more were considered alone, this finding would be 50%, which corroborates the fact that this is a typical chronic pathology found in elderly people.Brazil has experienced huge economic and social changes as of the 50s. The large rural exodus, for example, affected the population life style, who reduced the frequency and intensity of physical activities and increased the consume of industrialized products with high level of fat and sugar. These products led to obesity, dyslipidemia, systemic arterial hypertension and hyperglycemia, and as a consequence, increased metabolic syndrome prevalence. The first apparent consequence of changes in life style can be observed in the anthropometric changes in the individuals of this study. As previously described, around 70% of the chagasic population in this study had high overweight/obesity rates as well as increased waist circumference and percentage of fat mass over 30%. Other important findings of this study were changes in lipid profile, which are associated with increased adipose tissue, specially visceral adipose tissue. The latter is responsible for 2 important metabolic changes: (1) intensive lipolytic activity, which increases free fatty acids in portal and systemic circulation and reduces hepatic uptake of insulin, causing systemic hyperinsulinemia[8] and (2) suppressed release of VLDL from the liver (lipoprotein of very low density). These particles are rich in triglycerides which trigger a cascade of events causing a reduction in HDL (High Density Lipoproteins) and an increase in LDL (Low Density Lipoproteins), increasing the risk of cardiovascular events[17].Moreover, it must be pointed out that in this study the frequency of individuals with hyperglycemia anddyslipidemia were 24.3% and 75.7%, respectively.Hypercholesterolemia was the most frequent dyslipidemia followed by hypertriglyceridemia and reduction in HDL-cholesterol levels, which shows that increased adipose tissue affected the lipid profile. An association was found between increased waist circumference, increased triglyceride levels and decreased HDL-cholesterol levels.Overweight/obesity observed in the individuals also affected endocrine and immune profiles. The adipose tissue is not only an energy reservoir, but also an endocrine organ responsible for production of proinflammatory andinflammatory cytokines. Therefore, obesity contributes for a pro-inflammatory state and a consequent increased susceptibility to develop cardiovascular diseases,atherosclerosis, systemic arterial hypertension, insulin resistance and thrombotic events. Among the cytokines, adiponectins, leptins, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and factor of tumor necrosis (TNF-α) are specially important because they are associated with energy balance, oxidative stress and control of insulin response[18, 19, 20, 21].The increase in body fat is especially important for individuals with the indeterminate form of CD, as many studies have reported that the adipose tissue is also a Trypanosoma cruzi reservoir, and therefore, responsible for increased parasite load, increase in macrophages, and maintenance of low level of persistent chronic inflammation similar to that found in morbidly obese people. Some authors have also reported that there is an imbalance in the regulation process between pro- and anti- inflammatory cytokines with increased risk for tissue damage[22, 23, 24, 25, 26].Studies conducted in the last 10 years on anthropometric changes in populations from several countries have reported that increased weight specifically because of visceral fat, is the major risk factor for development of metabolic syndrome [27, 28, 29]. The Wc componentsand hypertriglyceridemia were more strongly associated with MSin thisstudy group.It is important to point out that the indeterminate form of CD could boost the risk of the individuals develop the cardiac form of this disease, as there are immunological and blood vessel wall changes, both favoring tissue injuries with consequent permanent damage.According to a systematic review and meta analysis performed by Gami et al (2007), the risk of CVD in individuals with MS is mainly higher in women, with relative risk (RR) of 1.78 (CI 95%, 1.58-2.00)[29]. Other review by Ford (2005) reported that the risk of CVD is 1.65 (CI 95%, 1.38-1.99) using the criteria of NCEP ATP III[30]. The same criterion was used in this study and RR of CVD, based on BMI, was 3.1(CI 95%, 1.72 – 4.48), and based on WC, RR was 2.22 (IC 95%, 0.84 – 3.60).Among the deleterious habits, smoking and alcoholism were not significant in this group (16.2% and 12.2%, respectively), but sedentariness was observed in almost 50% of individuals. Sedentariness is a very important characteristic under the standpoint of the metabolic syndrome, as besides impairing body weight, it causes deposition of visceral fat and impaired blood circulation with a consequent development of cardiovascular diseases.CVDs were the most mentioned pathologies in the family history of the participants in this studyfollowed byDiabetes mellitus followed and systemic arterial hypertension. Martins-Melo et al (2012) evaluated all deaths occurred in Brazil from 1999 to 2007 in which CD was reported as the main or related cause. The authors found that more than 40 % of them were directly related to cardiac complications and about 9.3% were associated with hypertensive diseases[31]. Many patients in this study reported that close relatives were carriers of CD as well as chronic pathologies, like those mentioned in the family history, but a few of them were aware of the relationship between them and CD.In light of these considerations, it may be stated that chagasic individuals with the indeterminate form of the disease, even those having normal BMI, but with fat mass percentage over the maximum allowed value (30%), increased WC, dyslipidemia, specially increasedtriglycerides and reduced HDL, are at higher risk of progressing to the symptomatic stage of the disease.

5. Conclusions

- The patients in this study are at high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases due to biochemical andanthropometric changes, mainly reduced HDL-cholesterol, increased triglycerides and waist circumference. The presence of metabolic syndrome in the whole population, as well as development of chronic non-communicable diseases, such as Diabetes mellitus type 2 and systemic arterial hypertension are age dependent. Carriers of Chagas' disease in Brazil have been in the age group over 40 years, and therefore, are more susceptible to those comorbidities and development of the disease itself.Reports on adipose tissue being a parasite reservoir also affects this group, as it presents a high amount of fat mass, and therefore a higher parasite load favoring a flare-up of the disease.According to literature data, a great possibility exists that these individuals have an altered pro-inflammatory cytokine profile, leading them to a low inflammatory level, and favoring tissue injury and development of chagasiccardiopathy. This group has been developing these characteristics with satisfactory outcomes.Using this approach, it is believed that the chagasic population should be better advised concerninginappropriate life style. Moreover, specific programs should be developed to fight obesity and sedentariness in this population, which would improve life quality of these patients and reduce expenses from the development of the disease.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML