-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2013; 3(1): 10-16

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20130301.02

Histopathological Study in Posterior Cruciate Ligament of Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis in Iraqi Patients

Sahar A. H. Al-Sharqi 1, Mahmood Shihab Wahab 2, Safaa K. Dheyaa Hussainy 2

1Dept. of Biology, College of Science, Al-Mustansiry University, Baghdad, Iraq

2Nursing home hospital, Medical city complex, Baghdad, Iraq

Correspondence to: Sahar A. H. Al-Sharqi , Dept. of Biology, College of Science, Al-Mustansiry University, Baghdad, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common disorder of the musculoskeletal system and is a consequence of mechanical and biological events that destabilize tissue homeostasis in articular joints. The present study focuses on some histological changes of posterior cruciate ligament in both (OA) and Rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Thirty patients with OA and 30 patients with RA were studied to determine the effects of OA and RA on the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) of the human knee joints. Microscopic examination of PCL with OA showed degenerative changes, aggregation of inflammation cells and congestion.In addition, section of PCL with RA showed hydropic degenerative changes with edema, ligamentocytes proliferation and aggregation of inflammation cells.The PCL histopathological changes of OA were less severe than in the RA.There was a weaker correlation between aging and total histological changes of PCL.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis,Posterior Cruciate Ligament, Histological Changes

Cite this paper: Sahar A. H. Al-Sharqi , Mahmood Shihab Wahab , Safaa K. Dheyaa Hussainy , Histopathological Study in Posterior Cruciate Ligament of Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis in Iraqi Patients, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 10-16. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20130301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease occurring mostly occurs in the knee1 and commonly seen in middle-aged and elderly adults2 ,is considered to be caused by multiple factors such as age, gender, genetic predisposition, mechanical stress, trauma, and weight3. People with OA often have joint pain and reduced motion. Unlike some other forms of arthritis, OA affects only joints and not internal organs4. Accordingly, OA is best modeled as a disease of organ failure, in which injury to one joint component leads to damage of other components, and collectively to joint failure and the clinical manifestations of OA5. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) the second most common form of arthritis affects other parts of the body6. RA is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by joint swelling, joint tenderness, and destruction of synovial joints, leading to severe disability and premature mortality7.The knee joint is the largest and one of the most complex joints in the human body. A unique interaction of bones, muscles, menisci, and ligaments results in a compromise between stability and mobility: the knee has to withstand stresses from body weight and (muscle) lever forces while at the same time it has to enable mobility to produce movement8.The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is an important knee structure.Together with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) they are essential for knee kinematics in anteroposterior tibial translation, tibial rotation, and as secondary restraints to valgus/varus forces9.Rupture of the PCL is most commonly associated with severe knee trauma and multiligament injury, but rarely occurs spontaneously or in isolation.The goal of the present study was compare histological changes in the PCL from a number of human knee joints across the entire adult age range with no history of previous joint trauma and to determine the correlation of changes in the PCL of OA with the PCL of RA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

- The PCL tissues were obtained during operations involving total knee replacement, from 30 patients with OA (aged 58-70 years) and 30 patients with RA (aged 40-73 years), in the Nursing home hospital/ Medical city complex. OA patients were diagnosed as having osteoarthritic knee joints on the basis of clinical symptoms, examination, and radiological findings; RA patients were diagnosed according to the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) or C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and X-Rays.

2.2.Tissue Preparation

- All PCL removed at surgery are fixed in 10% formalin solution.After fixation, the sections are processed, embedded in paraffin and 5μm thick glass mounted sections are prepared, which are routinely stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) according to 10.

3. Results

- All the PCL obtained from the OA and RA was stained with histological stain (H&E). On examination of these sections with light microscope, we were able to identify a number of histological changes with different proportions. These changes are:

3.1. Histological Changes of OA

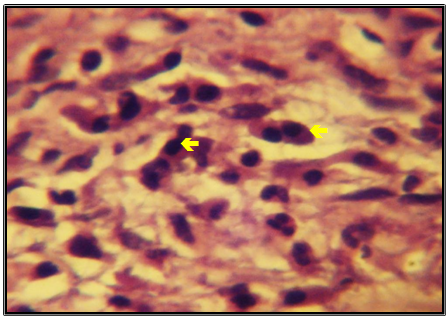

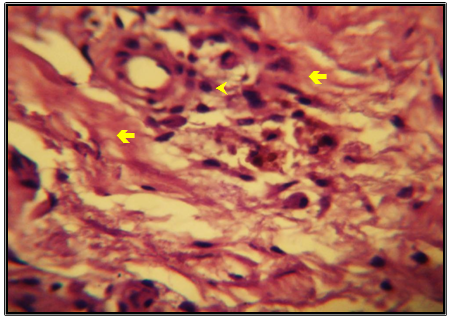

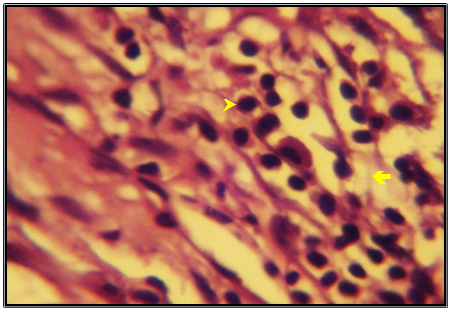

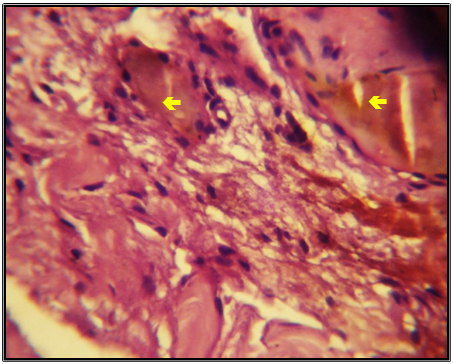

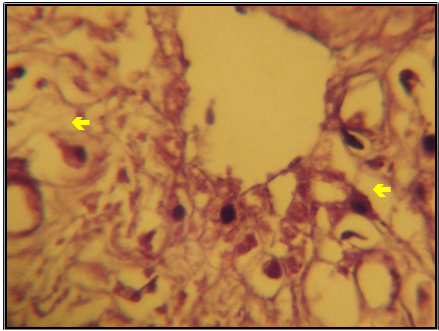

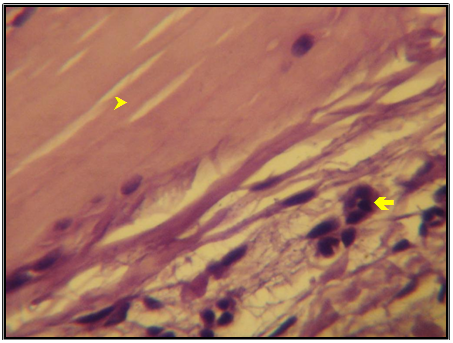

- Histology of the PCL showed changes secondary to degeneration and trauma. In most of the ligaments examined, aggregation of macrophages in PCL tissues were present (figure 1). On the other hand, sections of PCL of many patients showed congestion in all tissue with aggregation of inflammation cells (figure 2). Other important lesion identified in the present study was an increase aggregation of macrophages with degenerative changes and congestion in large area (figure 3).

| Figure (1). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from the OA Patient showing aggregation of macrophages (arrows), (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (2). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from OA Patient showing congestion (arrows) with infiltration of inflammatory cells (arrowhead), (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (3). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from the OA Patient showing aggregation of macrophages (arrowhead) with degenerative changes (arrow), (H&E X 400) |

3.2. Histological Changes of RA

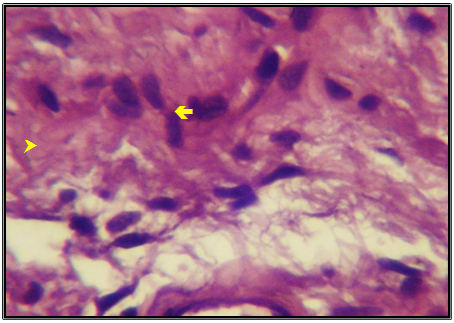

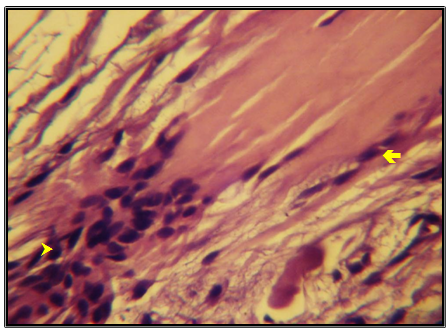

- Rheumatoid arthritis ligaments showed edema with neutrophils aggregation (figure 4), congestion with large area hemorrhage (figure 5). More, in chronic cases, hydropic degenerative changes with hemorrhage are already present (figure 6) and ligamentocytes proliferation with aggregation of inflammation cells (figure 7, 8).

| Figure (4). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from the RA Patient showing edema with neutrophils aggregation (arrowhead), (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (5). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from RA Patient showing congestion (arrows) with large area hemorrhage, (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (6). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from RA Patient showing hydropic degenerative changes (arrows) with hemorrhage, (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (7). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from RA Patient showing ligaments and tissues (arrowhead) with inflammation cells (arrow), (H&E X 400) |

| Figure (8). Light microscopic appearance of PCL from RA Patient showing ligamentocytes proliferation (arrow) with granulomatous reaction (arrowhead), (H&E X 400) |

4. Discussion

- Although disruption and loss of the articular cartilage is a hallmark of knee OA, the disease process results in changes in other knee tissues such as ligaments, menisci, subchondral bone and synovial membrane11,12.To understand better the changes in the PCL with OA and RA, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of major histological patterns of PCL pathology in human knees across the adult age. Overall, our findings indicate that PCL pathology in the context of knee OA is very distinct from ACL pathology13. Another study revealed that degeneration or rupture of the ACL strongly reflected the histological state of the PCL14, 15.The PCL begins to degenerate early but does not continue to degenerate with sever OA. The histological degenerative changes of the PCL in most of the specimens probably result from synovitis of the arthritic knee16. The presence of histological changes in most PCL of OA was in contrast to the findings of other authors 11, 17, 18.The alterations in collagen fibril affect the biomechanical properties of the ligament19, 20, and there is a decrease in collagen fibrils in the PCL in individuals older than 60 years21, 22.In our study, fiber proliferation was the earliest and most common change in the extracellular matrix of RA. It was also the most common histopathological change in patients younger than 45 years and was more common in the PCL of RA than the PCL of OA. It was also the only histopathological change in the PCL that increased continuously with the changes in the articular cartilage23. In a recent histopathological study, loss of the structural integrity of the collagen framework of the PCL was found in all patients with joint destruction16, 21. These findings suggest that the retained PCL is structurally and histologically abnormal. Histological evidence for inflammation was observed in the PCL knees of OA and RA. Examination of PCL tissues from patients with OA clearly shows evidence of inflammation, though this is not as aggressive as that seen in the RA. These findings correspond to the results of Kree et al 24.RA is the most common type of inflammatory arthritis.This inflammation is in the lining of the joints, and it will cause permanent damage to the bone and cartilage 25.Direct comparison of the PCL between 30 OA subjects and 30 RA subjects of human knee has shown more hyperplasia of the lining cell layer and cellular infiltrate composed largely of lymphocytes and monocytes, through to PCL which is thickened by fibrotic tissue in severe RA than in OA. However, OA is usually considered to be a primary disorder of chondrocyte proliferation and function with secondary changes in bone and it is often associated with an inflammatory response 26, 27.

5. Conclusions

- The PCL usually show degenerative and chronic traumatic change of varying degrees on histology. According to results of this study demonstrated that the repair and treatment of recent lesions of PCL are possible. According to our results we can conclude that is better to remove posterior cruciate ligament during the surgery.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML