-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2012; 2(5): 96-102

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20120205.02

A Transatlantic Comparative Study of Acute Dysphagia Services

Roger D. Newman 1, Tony Long 2

1Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Preston, Lancashire, PR2 9HT, UK

2University of Salford, Salford, M6 6PU, UK

Correspondence to: Roger D. Newman , Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Preston, Lancashire, PR2 9HT, UK.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

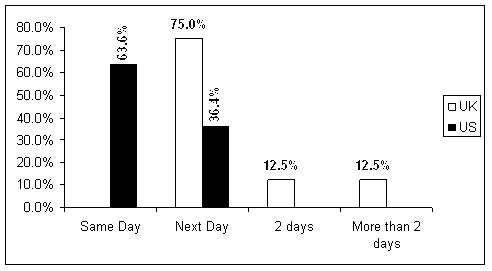

This was the first study to compare acute dysphagia service provision directly between the UK and the US. It examined variations in acute dysphagia services between the UK and the US, determined clinicians’ perceptions of their own service and that of their transatlantic counterparts, and elicited the reason for variation. An online survey was distributed to randomly-allocated teaching hospitals in the UK and the US, and speech and language therapists working with acute dysphagia responded anonymously via an automated system. Content analysis was employed to convert free-text responses to numeric data, and then this and existing numeric responses were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis. Variability was high, with the US having on average 0.95 whole time equivalent more clinicians per hospital than the UK. This resulted in an increased number of new patients examined and increased frequency of review of existing patients compared to the UK. In contrast, the UK had significantly increased waiting times with no patient being assessed on the same day as referral (compared to 63.6% of US responses). Notable variation was also seen in objective or instrumental assessment, with most US patients receiving videofluoroscopy or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (compared to only one UK hospital). Finance was found to be at the root of the variation. However, the more extensive US service was found to be more cost-effective.

Keywords: Swallowing, Dysphagia, Acute, Clinician, Transatlantic, UK, US, Variation

Cite this paper: Roger D. Newman , Tony Long , A Transatlantic Comparative Study of Acute Dysphagia Services, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 96-102. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20120205.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Dysphagia is generally defined as a disorder of swallowing solids and liquids from the mouth to the stomach[1] arising from a number of etiologies inclusive of neuromuscular diseases; head and neck cancers; autoimmune disorders and other general medical infections. Approximately 12% of patients in acute hospitals present with dysphagia which may be temporary or long-term[2]. This was further amplified in stroke research whereby dysphagia is usually found in 29-45%of patients in the acute stage of stroke and approximately 20%at 4-month follow-up[3]. Aspiration (foods or fluids entering the airway) is one of the critical signs of dysphagia, and approximately one-third of patients with dysphagia develop pneumonia requiring acute treatment[4][5]. Other reports based on insurance statistics suggests that in the United States alone, between 8,000 and 10,000 individuals die from choking each year[6]. The introduction addresses key evidence relating to speech and language therapy, health care systems in the US and the UK, and the assessment and management of dysphagia to set the context for the study.

1.1. Speech and Language Therapy

- Dysphagia is a recognised role of the Speech and Language Therapist (SLT) in the United Kingdom (UK) and Speech-Language Pathologists (SLP) in the United States (US). Research shows the importance of the SLT within the assessment, treatment and management of dysphagia in the oral and pharyngeal stages of deglutition[7], and bedside examination is the standard initial assessment utilised to highlight the precise and early diagnosis of dysphagia. Further examination via instrumental means is available such as a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFS). This is a radiological swallowing evaluation often described as the gold-standard for the assessment of dysphagia[8][9]. However, this inevitably increases the cost of dysphagia assessment and management, together with the expertise of the SLT/SLP, and as such may significantly vary in each hospital throughout the country.Secondary to the huge variations in initial training of, and resources available to SLTs/SLPs throughout the world, many forms of instrumental examination may not be possible. Indeed, there may be further variations in actual service provision to patients with dysphagia which are currently unknown. This may be further amplified by the huge variations in healthcare systems between the UK and the US.As a result of the vast dissimilarities between each country’s method of healthcare funding inclusive of their respective employees and services offered, together with some degree of variation in undergraduate and/or postgraduate education of SLTs/SLPs and their ensuing proficiency and autonomy, this pilot study examined if the acute dysphagia services offered to patients in the UK versus the US also vary, from initial assessment and instrumental examination of swallowing, to the therapists’ attitudes towards whether they themselves believe they are offering a good service, and questioning which country they consider offers the best opportunities for therapists and service(s) for patients.This research therefore focussed on the potential transatlantic variation(s) in service provision for acute dysphagia, and therapists’ perceptions of their counterparts’ resources to examine if they are indeed similar, or if the variation in healthcare provision extends further to the patient with acute dysphagia.

1.2. Health Care Systems in the UK and the US

- The US health care system is reported to fall well below acceptable standards for access and efficiency of care[10], outlining what needs to be done to improve the current problems and deficiencies in the health care system. Solutions are also provided in the form of evidence-based decision making to move into a more positive and uncharted direction. Those professionals targeted to provide the evidence base are the ones at the heart of health care themselves, and not the managers, though funding from management is obviously necessary to enable healthcare workers to create the vital evidence base desired.A recent report asked the question of whether the US has the best health care system in the world[11]. One vital factor raised was that there are no established criteria for measuring the quality of national health care systems. The report went on to criticise the World Health Organisation (WHO) for their report[12], which used five criteria for measuring the quality of health care: Health Level; Health Distribution; Health Responsiveness; Responsiveness Distribution; Financial Fairness, and stated that only criteria 1 and 3 are clinical measures of health care systems, while the remainders are those looking at the inequality of distribution. What the critique does not accept is that the financial constraints a country’s health care system has (and in the case of the US the general public’s financial constraints) directly influences its quality. Though no direct comparisons are made between the US and the UK, there are various other comparisons between the US and other countries of the world. While the WHO report[12] shows the US to rank 37th in terms of overall performance, some researchers are convinced that the US has the best system based on various criteria of their own[11].Further literature review revealed that between 85-96% of US citizens favoured healthcare access for all[13]. This seems to other authors that although US citizens are unhappy with the current health care funding system, they would prefer not to pay for healthcare for those who are unable to pay for it themselves[14]. Indeed, present US politics show in the current climate of President Obama’s desire to create uniform healthcare access to all, the US healthcare system as it stands is only beneficial for those who can afford it, creating a great deal of debate amongst much of US society. However, despite the four main systems of US health care funding, this still leaves approximately one sixth of the American population uninsured[15]. This amounts to more than fifty million individuals.A better document for measuring success showed the opinion of the NHS from the perspective of its users whereby evidence collated from various surveys and showed that on the whole, the British public seem happy with the NHS, but compared this to whether they agreed with a statement from the Commonwealth Fund (2007)[16] that “our healthcare system has so much wrong with it that we completely rebuild it”[17]. The report showed that only 15% of British people agreed with this, a very small percentage upon which to actually act and create a totally new healthcare system. It also shows that on the whole, public support for a universal, tax funded NHS remains high. The argument is put forward from a particular political stance which significantly limits the value of such a report, and there are more favourable and less contentious ways of presenting his findings.

1.3. Dysphagia Assessment and Management

- Recent research examined dysphagia assessment practices of SLTs in the UK and established levels of consistency[18]. The results were then compared to previous research of reported practices of clinicians in the US[19]. As a result, the comparative research from which the results were obtained was indirect. This is due to the fact that there was a four year gap between the completion of each research, during which time practice as a whole may have progressed or altered significantly. In addition, the secondary research showed adaptations and modifications to the US research questionnaire[18], making the UK questionnaire invalid for true comparison.As with comparisons of health care systems, a lot of literature focuses upon education of SLTs/SLPs[20][21], highlighting the main factors that education to Masters or postgraduate level is required to become credentialed as an SLP in the US, a qualification which is obtained only after four years of undergraduate study to Bachelor’s level. This varies from UK systems where three to four years undergraduate study will provide the necessary formal and clinical education to fulfil requirements for clinical licensing. Despite the descriptions of education, it was noted that practice in dysphagia is not mentioned, and therefore no UK/US comparisons could be drawn.

1.4. Study Questions

- The significant lack of literature directly related to comparison between dysphagia practice in the UK and the US prompted the questions of whether variation exists in the assessment, treatment and management of acute dysphagia; whether individuals have the same levels of autonomy to practice; if education is at the route of any dissimilarities, and if funding (with politics at its source) plays a key role.

2. Method

- This was a pilot study with a view to creating a larger study at a later date based upon the results obtained. It was a descriptive, comparative design using mixed quantitative and qualitative methodology with no attempt to match pairs since there was no service user involvement. The study relied on an online questionnaire accessed anonymously by comparable practitioners in the UK and the US sent to five randomly allocated hospital sites in each country. Thirty five appropriate questions pertinent to acute dysphagia services both in the UK and the US were created and one questionnaire was formed which was sent out to all participants whether in the UK or the US. The questions were formed using mixed quantitative and qualitative formats using both closed and multiple choice questions with a maximum of 10 having the opportunity to add free text as appropriate. Simply completing the questionnaire would return their responses automatically and anonymously to the questionnaire’s website, and not from the participants' own e-mail address. All data were stored in this way and could not be traced back to the participant themselves. If they chose to complete the questionnaire, this was seen to be informed consent, and no signature or consent-confirming e-mail was distributed. If the clinician chose not to complete the survey or did not give their consent, they could simply delete the e-mail and no further action would be taken.One of the major benefits of questionnaire’s website was that all the survey data could be downloaded to the subscriber’s personal computer for storage and analysis.Data was automatically drawn from the results in the following ways:1. Total number of respondents2. Total number of UK versus US respondents3. Response counts extracted from the package in the form of percentages for all Multiple Choice Questions and transatlantic comparison was made. In addition, where the choice of responses was numeric to demonstrate the number of clinicians, number of patients on the caseload, and number of new referrals received per week, this was directly compared against other responses in the form of: UK vs. UK; US vs. US and UK vs. US. This highlighted variation in the respondents’ own country as well as for transatlantic comparison.4. Where qualitative responses were an option, for example when considering clinician autonomy, these were evaluated via the use of content analysis, extracting the key words to form content-related categories or themes. Where no theme was present, each view was presented individually and discussed accordingly.5. All results obtained were then analysed by simple visualisation and counting to establish where variation in practice existed, and if this corresponded with what that particular country’s clinicians thought of their transatlantic counterpart’s services and post-graduate education.

3. Results

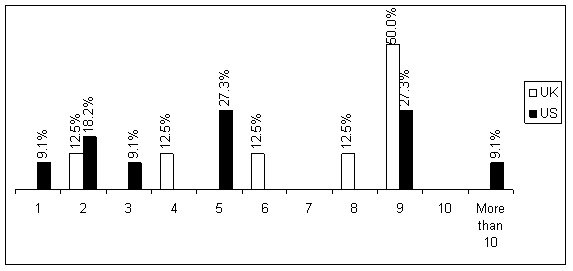

- There were 15.8% more respondents from the US than there were from the UK, and while all UK respondents stated that the NHS provided funding for all acute dysphagia services, there was obvious variation in the source of funding for US clinicians, including private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans’ Affairs, or a combination of all four. No UK respondent stated funding was from any other source except the NHS.In terms of individual responsibility, both countries’ respondents provided comparable results for dysphagia specialist roles, and results showed that 37.5% of UK participants and 27.3% of US participants have 76-100% of their role spent with acute dysphagia. However, as seen in Figure 1, the number of clinicians in each country’s department working with acute dysphagia varied significantly, with the UK providing a higher average response, while the US had a greater spread of responses.

| Figure 1. Number of clinicians in the department working with acute dysphagia |

| Figure 2. Time period between referral and assessment |

4. Respondents’ Perspective

- With regards to equality of service access, a comparable majority response rate was noted for clinicians’ giving preference to their own country. Only one UK clinician (12.5%) perceived the US to have a fairer system, the remaining responses (87.5%) favoured the NHS. Three US clinicians (27.3%) also stated that the NHS has fairer service access, the remainder either stated that they preferred the US system, or were unsure.However, with regard to acute dysphagia healthcare, fewer UK clinicians (50%) thought actual dysphagia healthcare in the UK is better than that of the US, whose clinicians (81.8%) considered their own country to have preferential service provision. Funding and finance were seen to be the theme for all of the UK clinicians’ reasons for choosing the US system of access; and the NHS was the reason for the two (18.2%) US clinicians who preferred the system in the UK.Paying specific attention to respondents’ perception of funding implications, while all UK respondents considered funding has implications for their work in dysphagia, fewer US clinicians (72.7%) felt the same way.The majority of UK clinicians (62.5%) considered that the US has greater access to funding, with only one clinician (12.5%) believing the UK to have greater funding. No US clinicians believed this to be the case. Indeed, a greater number of US clinicians (n=3) considered the UK has greater access to funding than UK clinicians themselves. The remaining respondents (UK = 2 and US = 8) reported that they did not know.When asked about post-graduate training, the majority of both countries’ respondents stated that they did not know which country offers greater access to post-graduate training. However, of those participants from both the UK and the US who provided a response, the USA achieved a majority from both countries’ clinicians. No US clinician considered the UK has greater access to post-graduate training.In summary, while half of UK respondents stated that they considered their own country to offer a better service, only one US participant (9.1%) agreed. The remaining UK respondents believed the US to have a better service, and the majority of US clinicians (90.9%) also considered this to be so.

5. Discussion

- The results show that there is considerable variation and inequality of both access to, and provision of general healthcare and acute dysphagia services in both the UK and the US. In addition, the general trend of finance and funding being at the root of the disparity was prevalent throughout both countries’ responses. In terms of the variations between the UK and the US, the results show that there are gaps in all aspects of service provision.If a patient suffering from dysphagia is admitted to hospital in either the UK or the US, it would be expected that they should be eligible for the same service as another patient, but the study suggests otherwise. The reported lack of funding in both countries for patients with acute dysphagia (and the disorder(s) prompting the onset of dysphagia) is resulting in an inequality of service provision. It appears that some patients are being treated more often than others, and indeed those in the US receive treatment over a weekend. The study suggests that the lack of clinicians as a result of the lack of funding is the source of the problem of unequal service provision. But while inequalities may be being addressed in the UK[23], the USA still has one of the worst healthcare systems of modern industrialised nations[24] where considerable inequalities exist.The variability in therapist expertise is a potential factor for consideration. As both VFS and FEES are specialised examinations, if there isn’t a clinician available to complete such examinations, then the SLT/SLP service will not be able to offer them to their patients. So the fact that the US offers more routine VFS/FEES may in fact indicate a superior level of clinician expertise than the UK, though this cannot be proved. In addition, because both VFS and FEES are expensive procedures[25], funding is another issue which is highly likely to impact upon such service provision. The results of greater routine VFS/FEES in the US therefore show it could impact more in the UK.However, although fewer US clinicians considered that funding has implications for dysphagia service provision than UK clinicians, the majority of them considered that the US has greater access to money to provide the necessary resources. This indicates that in general, US clinicians understand the implications of finance for service provision, but not all were prepared to state outright that they do. It is also possible that some US clinicians understand the financial constraints of the NHS, but do not grasp the concept of their own country’s financial limitations for health care.Neither UK nor US respondents were able to definitively state if they considered their own country preferential for dysphagia treatment, or for general health care. Some clinicians thought that their own country was preferential for both of the above, while others favoured their transatlantic counterpart. While variations in clinicians’ thoughts were apparent, it is quite poor that some considered the healthcare system in the country in which they work to be somewhat less superior to that of another country.The UK’s National Health Service and the USA’s various healthcare insurance schemes obviously prevent patients from accessing the acute dysphagia services they require, and it appears the only way to improve this is to boost the amount of money available to increase the number of clinicians, particularly in the UK where the number of clinicians is in fact falling, while the amount of patients to be treated is increasing. In comparison, it remains to be seen whether the plans of the US President to introduce a ‘National Health Service’ will improve service provision, both in general and with regards to acute dysphagia care.The issue of the time delay between the receipt of referral and the assessment of the patient illustrates a distinct variation that the impact the number of clinicians has. Most US patients were reported to be assessed on the same day as receipt of referral despite the lack of national guidelines regarding time delay from their governing body, indicating that a greater number of clinicians per department and greater seven day service will provide a preferential service. Likewise, UK patients have an increase in the number of days to wait until they receive treatment after they are referred, despite national guidelines from the governing body. This could demonstrate either a smaller number of clinicians in the department or a reduction in the clinician to patient ratio, but in general there appears to be more clinicians in the US providing a more speedy service. The shortfall in the UK service can clearly be assigned to a lack of clinicians and seven day service, which the US SLP services demonstrate and at which they excel.The majority of responses show that UK clinicians offer dysphagia management rather than therapy. If the most prevalent UK response for the number of times a patient is treated per week is only one, it is doubtful whether therapeutic input provided so few times at the acute stage of the disorder would be of much benefit[26]. In addition, the increase in the number of US clinicians offering therapy as opposed to management could indicate an increase in the number of clinicians in the department.As regards dysphagia screening reducing pressure on SLT departments, it is proposed that the 37.5% of negative UK responses were received because the SLT departments offer this training, therefore not releasing time to see those patients who have failed such a screening and require more formal SLT dysphagia assessment. However, studies show that hospitals with a formal dysphagia screening programme have a significantly decreased rate of pneumonia[27]. Although UK respondents may consider it does not reduce the pressure on their department, they adhere to this guideline, but not all US sites are offering such a service, and are at risk of introducing further inequality and reduced strength of service.When considering whether acute dysphagia service provision is better in the UK or the US, funding was a prevalent response to those questions enabling qualitative statements. In general, the theme of all responses indicated that the US provides a preferential service. The response from one UK clinician who reported that ‘For those who can afford / have appropriate insurance, everything is available’ corroborates the idea of funding and finance as a source for UK respondents’ answers of preferential service provision in the US.However, the questions in the study were asked of service providers. Although service users would not be asked exactly the same questions, they may provide very different answers indicating a preferential acute dysphagia service in the UK. The question of access to services is currently undergoing US political scrutiny, and many US citizens appear to be against the idea of creating ‘access for all’. However, those US citizens in favour of ‘access for all’ state that the large number without insurance create hidden costs which are currently shared, so to expand coverage would reduce these costs and potentially improve the quality of health care[28].The study showed that finance is at the root of each country’s variation in practice, be it the funding of clinicians, objective instrumental assessment, or increased service cover. However, participants appeared unable to see the various benefits of service and practice, both of their own system and that of their transatlantic counterparts, and indeed this may also be the source of the problem. The difficulties seemed to be that each country’s clinicians are educated to practise in particular ways, potentially to varying standards, though they were unable to acknowledge this as one of their own strengths. Although many of the participants were able to see the downfalls of their services, many (particularly those of the US) were unable to see why this was.In addition, many US participants could not recognize the impact that a greater number of clinicians per department has, but this is probably due to the fact their attention has not been drawn to the lack of other country’s clinicians to which they can compare their own service. This study will therefore educate each country’s clinicians and potentially budget holders to provide insight into their own strengths and weaknesses, and enable them to learn from each other to provide a better system. While significant financial restrictions may make this difficult, the ‘template of learning’ has now been created, showing that although funding is vital to improve service provision, this is the only way forward, potentially by offering a greater degree of seven day service in the UK; enabling an increased length of stay in US hospitals, and ultimately educating undergraduate and postgraduate SLTs/SLPs in both countries to appreciate the service they currently have and what they can do to improve it.From the results obtained, it appears that the US is currently offering a higher standard of service to patients with acute dysphagia for a number of reasons: increased number of clinicians; increased seven day / on-call service and greater objective/instrumental assessment. However, a major difference between the UK and the US is that of service access. While the US may indeed be offering a better standard of service, not all patients are able to access it due to a potential lack of an appropriate level of insurance. This is something that the NHS prevents with access for all, but in doing so it increases waiting time for service response. This is intensified by a reduced number of clinicians in comparison to the US. This therefore clearly demonstrates the need for each country to learn from one another, seeing the benefits of the variation in service provision to create an equal service with access for all and speedy response.

6. Conclusions

- The greatest need now is for budget holders to realise the potential this study holds, altering acute SLT/SLP services as necessary, beginning with undergraduate/postgraduate education, and concluding with increasing funding for more valuable, advantageous and enviable services. This pilot study will provide the basis for such education and potentially increased funding, but inevitably a more in-depth study with a large sample to allow for stronger statistical testing, and inclusion of budget holders and service-users will be necessary to modify continuing excellence of service provision.As health care systems progress or change, and funding increases or decreases, it will be necessary to repeat this study, but to a higher level, taking into account the responses obtained; the need for national and local ethics approval, and inclusion of questions omitted from the pilot study. The perspective of service users should also be considered, particularly in light of scheduled political change and US healthcare reform. It should create a greater understanding of transatlantic strengths and weaknesses, so each country can learn from one another, and improve their own acute dysphagia services.

References

| [1] | Gerhard Böhme, “Sprach- Sprech- Stimm und Schluckstörungen. (Band 1: Klinik)” Urban & Fischer: Stuttgart, 2006. |

| [2] | Bronwyn Jones and Martin W. Donner, “Normal and Abnormal Swallowing” Springer: New York, 1991. |

| [3] | Muriel R Gillick, “Rethinking the Role of Tube Feeding in Patients with Advanced Dementia” New England Journal of Medicine, vol.342, pp.206–10, 2000. |

| [4] | Giselle Mann, Graham J Hankey and David Cameron “Swallowing Function After Stroke: Prognosis and Prognostic Factors at 6 Months” Stroke, vol.30, no.4, pp.744–748, 1999 |

| [5] | Carol A Smith Hammond and Larry B Goldstein, “Cough and Aspiration of Food and Liquids Due to Oral-Pharyngeal Dysphagia: ACCP Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines” Chest, vol.129[Suppl.1] pp.154S–168S, 2006 |

| [6] | Bronwyn Jones “Normal and Abnormal Swallowing: Imaging in Diagnosis and Therapy” Springer: New York, 2003 |

| [7] | Ralf-Joachim Schulz, RolfNieczaj, AlmutMoll, et al., “Dysphagia Treatment in a Clinical-Geriatric Setting PEG and Functional Therapy of Dysphagia” Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, vol.42, no.4, pp328-35, 2009 |

| [8] | Stephanie K Daniels, Colleen P McAdam, Kevin Brailey, et al., “Clinical Assessment of Swallowing and Prediction of Dysphagia Severity” American Journal of Speech Language Pathology, vol.6, no.4, pp.17-23, 1997 |

| [9] | JoAnne Robbins, James L Coyle, John C Rosenbek, et al., “Differentiation of Normal and Abnormal Airway Protection During Swallowing Using the Penetration-Aspiration Scale” Dysphagia, vol.14, no.4, pp.228-232, 1999 |

| [10] | Elaine T Miller “Rehabilitation Nursing’s Responsibility in Shaping the Future U.S. Health System” Rehabilitation Nursing, vol.33, no.6, p.230, 2008 |

| [11] | Ronald D Wenger “Does the US Have the Best Health Care System in the World?” Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, July pp.8-15, 2009 |

| [12] | World Health Organisation “Health Systems: Improving Performance” WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2000 |

| [13] | Online Available:http://admin.cms2005.com/docServer.aspx?f=NTc0Nzk3MDE |

| [14] | Robert J Blendon, Mollyann Brodie, John M Benson, et al., “Americans’ Views of Health Care Costs, Access and Quality” The Milbank Quarterly, vol.84, no.4, pp623-657, 2004 |

| [15] | MR Nuwer, GJ Esper, PD Donofrio, et al., “The US Health Care System. Part 1: Our Current System” Neurology, vol.71, pp.1907-1913, 2008 |

| [16] | Online Available: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files |

| [17] | Tony Delamonthe “How the NHS Measures Up” British Medical Journal, vol.336, pp.1469-1471, 2008 |

| [18] | Claire Bateman, Paula Leslie and Michael J Drinnan “Adult Dysphagia Assessment in the UK and Ireland: Are SLTs Assessing the Same Factors?” Dysphagia, vol.22, no.3, pp174−186, 2007 |

| [19] | Barbara A Mathers−Schmidt and Mary Kurlinski “Dysphagia Evaluation Practices: Inconsistencies in Clinical Assessment and Instrumental Examination Decision−Making” Dysphagia, vol.18, no.2, pp.114−125, 2003 |

| [20] | Dolores E Battle “The Education of Speech-Language Pathologists in the United States of America” Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, vol.58, pp.7-13, 2006 |

| [21] | Jeri A. Logemann “Preparation of Speech-Language Pathologists in the United States: The Master’s Degree” Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, vol.58, pp.55-58, 2006 |

| [22] | Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists “Communicating Quality 3” RCSLT, London, UK, 2003 |

| [23] | Adam Oliver and Don Nutbeam “Addressing Health Inequalities in the United Kingdom: A Case Study” Journal of Public Health Medicine, vol.25, pp.281-7, 2003 |

| [24] | Dennis Raphael and Toba Bryant “The State’s Role in Promoting Health: Public Health Concerns in Canada, USA, UK, and Sweden” Health Policy, vol.78, pp.39-55, 2006 |

| [25] | Roger D Newman “Videofluoroscopy” In: Julie M Nightingale, Robert A. Law (Eds.) “Gastrointestinal Tract Imaging: An Evidence-Based Practice Guide” Elsevier, UK, 2010 |

| [26] | Alyssa Banotai “Exercise Science and Dysphagia Therapy” Advance, vol.20, no.12, pp.7-9, 2010 |

| [27] | Judith A Hinchey, Timothy Shephard, Karen Furie, et al., “Formal Dysphagia Screening Protocols Prevent Pneumonia” Stroke, vol.36, pp.1972-1976, 2005 |

| [28] | Online Available: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2004/Insuring-Americas-Health-Principles-and-Recommendations.aspx |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML