-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

2012; 2(2): 10-13

doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20120202.03

Level of Awareness of Hpv Involvement in Prostatic Cancer Among Different Cadres of Medical Doctors

Ajobiewe Olu Joseph 1, Isu Nnena Rosemary 1, Agwale Simon 2, Ajobiewe H. F 3, Dangana A 4

1University of Abuja, Department of Biological Sciences , Faculty of Natural Sciences, PMB 117, Gwagwalada, Federal Capital Territory (F.C.T.) Abuja Nigeria

2Innovative biotechnology Inc3516, Langrehr Road, Suite 2A, Windsor M.ill. MD 21244, USA

3Regina Pacis College P.O.BOX 4868, Abuja

4Medical Microbiology Department, Federal Medical Centre Bida. Niger State .Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ajobiewe Olu Joseph , University of Abuja, Department of Biological Sciences , Faculty of Natural Sciences, PMB 117, Gwagwalada, Federal Capital Territory (F.C.T.) Abuja Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Clinicians most times pay less attention to the relevance of HPV in prostatitis either deliberately or ignorantly; hence , this study intends to unravel this sort of attitude through interrogation of the different cadres of doctors. Informed consent research questionnaires were administered to the various cadres of medical doctors at the various locations earmarked for this study -using the Stratified sampling technique . Some questions were deliberately ignored in order to concentrate on the level of awareness of HPV involvement in prostatitis among the various cadres of Medical Doctors. Results showed that the level of awareness among these cadres of doctors were significantly very low (P<0.05) which underscores their choices of tests.

Keywords: Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Awareness, Prostate, Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH)

1. Introduction

- Several studies have examined the presence of HPV in prostate cancer tissue with varying outcomes. Utilizing PCR and in situ hybridization techniques, some have noted the presence of HPV-16 in up to 20% of prostate cancers 1 , 2. In contrast, a case–control study by Strickler et al 3 that employed two HPV serum antibody assays as well as two different PCR primer sets in two distinct ethnic populations did not demonstrate an association between HPV-16 tissue positivity and prostate cancer 3. Other negative tissue studies with regards to HPV-16 have also been reported 4, 5. Differences related to tissue handling and detection method/ technique, as well as possible tissue contamination by agents in neighbouring areas (e.g. urethra), most likely account for the discordant results thus far reported regarding HPV-16 and prostate cancer4 . For infections to account for anything but a small proportion of the risk of prostate cancer in the US population the prevalence of the infection must be relatively high. Thus, infections such as Cytomegalovirus(CMV), Human papilloma virus (HPV) and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV ) may be more important risk factors for prostate cancer than the now less common STIs such as syphilis and gonorrhoea. Further investigation is needed before definitive conclusions can be stated regarding the link between STIs

2. Study Design/Methods

- Stratified sampling technique was adopted at each study location. Subjects interviewed were selected from defined cadres of Medical Doctors viz; Internship Doctors, Resident Doctors, Registrars, Senior Consultants and Chief Consultants. The subjects interviewed through well structured questionnaires were served from each stratum at random. Out of the entire population of Doctors at a particular location, all the strata were equally represented. For instance in a location where there were only twenty consultants, the same number of subjects at the other strata( such as Residents, Registrars e.t.c) were individually interviewed at random. The one- way Analysis of variance (ONE WAY ANOVA)technique was used in the Statistics test of significance.HypothesisHo; There is no significant difference in the percentage mean level of awareness i.e. ( μ1 = μ2= μ3= μ4= μ5) of HPV involvement in prostate cancer cases among the various cadres of Medical Doctors.Ha; There is significant difference in the percentage mean level of awareness i.e.( not all the μi are equal) of HPV involvement in prostate cancer cases among the various cadres of Medical Doctors.Where;i = 1,2,3,4,5 representing the various cadres of doctors and μ is the mean percentages of their levels of awareness of HPV involvement in prostate cancer cases

3. Result

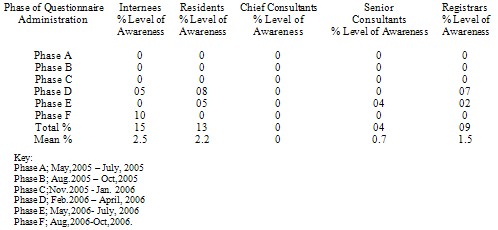

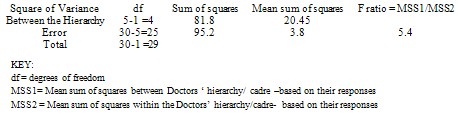

- Table 1 below shows the different phases of randomized interrogation through the administration of questionnaires to different categories of Medical doctors who clerk patients in different health settings. Phase A study took place between May 2005 to July, 2005. None of the one hundred internship doctors interviewed had any awareness {0/100 ( 0%)} . Similarly, none of the one hundred resident doctors interviewed had any awareness,{0/100 (0%) } ; Same trend was observed in the chief consultants and senior consultants, in other words none out of the one hundred interviewed in each of Chief consultants and senior consultants cadres i.e.{ 0/100 (0%)} . None out of the one hundred registrars { 0/100 (0%)} could associate HPV DNA prevalence with the prostatic cancer in the first phase of the study. Similar trends were observed in phases B and C. These took place from August 2005 to October,2005 and November, 2005 to January, 2006 respectively. In phase D, of administration, only five out of the hundred internship doctors{( 5/100) ( 5%)} interviewed consented to any level of association between HPV DNA prevalence in prostate tissue, while eight out of the one hundred resident doctors {8/100), (8)%} had similar line of reasoning and also seven out of the one hundred registrars { 7/100 ,(7%) } shared the same view; however, none out of the one hundred { 0/100,( 0%)} interviewed in each of the cadres of the chief consultants and senior consultant medical doctors recorded any awareness. In phase E , of the administration of questionnaires which took place between May, 2006 to July 2006, again internship medical doctors, Chief consultants, each in their group had zero awareness level out of one hundred interviewed in each cadre i.e.{ 0/100, (0%)} . Resident doctors awareness was again five out of one hundred interviewed { 5/100,( 5%)} and Senior consultants were four out of one hundred interviewed {4/100, (4%)} . In the last ,G phase of the study at yet another location- “which was conducted from November,2006 to January ,2007” - Resident doctors, Chief consultants, Senior consultants, and Registrars each in their various groups had zero awareness out of one hundred interviewed in each cadre {0/100 , (0%)}: the internship medical doctors , however, at this location had ten responses in support of awareness out of the one hundred of them interviewed {10/100, (10%)}. . The total level of awareness by the internship students was 15% with a mean of 2.5%. Those of the resident doctors was 13% with a mean of 2.2%.Chief consultants medical doctors had overall 0% level of awareness while Senior consultants had 4.0% level of awareness with a mean of 0.7% ; Registrars medical doctors had 9/100 (9%) level awareness of HPV DNA involvement in prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia.HypothesisThe alternate hypothesis is retained as there is a significant difference in the levels of awareness among the different cadres of the Doctors. As shown in table 2 ( From the F- ratio of 5.4 that is higher than the tabulated F value in the statistics table) The much younger doctors seem better informed than their consultants(both chiefs and seniors ).

|

|

4. Discussion

- The 0% and 4% responses received from Chief Consultants and the senior consultants respectively support their reluctance in associating HPV infection with prostatitis. They tend to believe more in its association with cervical cancer. However it seems the much younger doctors who still have greater passion and flare for research were better informed in this regard. In the other publication from this work, oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18 prevalences were high in archival prostatic cancer tissues. This makes it important risk factor in prostate cancer. Similar report had been documented 4 . Clinicians at the Urology clinics need to regularly include HPV diagnosis among their routine battery of tests to know the prevalence in various localities- most especially when probing Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH), and prostate cancers in Men. In fact greater emphases should be laid on HPV screening than screening for the etiologic agents of other STI in Prostatitis- such as concentrating on syphilis and gonorrhoea etiologic agents. This is borne out of the fact that in other parts of this study, marginally higher odds of positive syphilis serology and other etiologic agents of STI were obtained among prostate cancer cases and Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH) cases than among controls that were set up alongside. This trend had also been similarly observed by Hages et al 6 . This could be done inclusive of other genetic assays, viz RNASEL, MSR1, GSTP1, NKX3-1, Germ line variations , Somatic, Hormonal assays, immunological assays as it is the current practice. More recently, other epidemiological studies have begun to investigate associations between individual STIs and prostate cancer by serology, i.e. the detection of serum IgG antibodies against these agents. Five such studies have investigated human papilloma virus (HPV) serology and prostate cancer, one of which observed a statistically significantly higher risk of prostate cancer among HPV-16 seropositive and HPV-18 seropositive men, known high-risk serotypes for cervical cancer among women, but not among HPV-33 nor HPV-11 seropositive men 7 , 8. Two other studies observed a slightly but not statistically significantly higher HPV-16 seropositivity among prostate cancer cases than among controls 9 , 6, while two additional studies found no association between HPV-16 seropositivity and prostate cancer risk when comparing prostate cancer cases with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or normal controls 9 ,10 . It is important to note that while HPV is known to be an oncogenic virus, its influence on prostate carcinogenesis may be independent of inflammation. To date, studies investigating Chlamydia trachomatis serology and prostate cancer have reported null results 8. Hayes and colleagues observed marginally statistically significantly higher odds of positive syphilis serology among prostate cancer cases than among controls 6. Two studies have investigated herpes simplex virus (HSV- 2) serology and prostate cancer, one of which detected significantly higher odds of HSV-2 serology among prostate cancer cases than among BPH controls 11, while the other observed no such association 12. Recently, Hoffman et al 13 conducted a case–control study of human herpes virus (HHV) 8 serology and prostate cancer, in which they observed significantly higher odds of HHV-8 seropositivity among prostate cancer cases than among controls in two study populations 13. A previous examination of HHV-8 seroprevalence among black men from South Africa, however, failed to reveal an association with prostate cancer 14. HHV-8 is of particular interest for prostate cancer because it encodes viral IL-6, a protein that shows homology to human IL-6. Viral IL-6 has been shown to promote growth of human cells in vitro and to activate the human IL-6 signalling cascade involved in inflammation 15.Serological assessment has the advantage of assaying for an infection that may have resolved long before prostate cancer was detected. Put another way, the absence of histological evidence of an STI in prostate cancer specimens does not rule out a potential role of STI in prostate carcinogenesis. A possible disadvantage of serological testing for STIs is that a positive result does not necessarily mean that the prostate itself was infected by that particular organism, although this may be a reasonable assumption, in particular for agents that are frequently asymptomatic in men (e.g. C.trachomatis). Even so, actual prostate infection with an STI may not be required to induce an inflammatory response within the prostate. Infection anywhere within the genito-urinary tract may induce an inflammatory response in contiguous anatomic sites, including the prostate. Another avenue that has been pursued to investigate associations between STIs and prostate cancer is tissue analysis. It is important to note that STIs detected in prostate cancer tissues could have been acquired after the initiation of prostate cancer. Samanta and colleagues 16 recently noted the presence of human cytomegalovirus, a very common HHV 17 nucleic acids and gene products in patients with prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and prostate cancer16 . No information was cited in this report concerning prior medical history of either prostatitis or STI. In an analysis of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), also a common HHV 18 and prostate cancer Grinstein et al19 observed that 7/19 (37%) of prostate cancer cases evaluated displayed EBV by immunohistochemistry and PCR19 . Prior EBV infectious history was not discussed in this report. Tissue analyses of human HSV-2 in benign and cancerous prostate tissue have yielded null results 20 21 22 . Several studies have examined the presence of HPV in prostate cancer tissue with varying outcomes. Utilizing PCR and in situ hybridization techniques, some have noted the presence of HPV-16 in up to 20% of prostate cancers 1, 23 , 2 . In contrast, a case–control study by Strickler et al 3 that employed two HPV serum antibody assays as well as two different PCR primer sets in two distinct ethnic populations did not demonstrate an association between HPV-16 tissue positivity and prostate cancer3.The involvement of HPV in cervical cancer is no longer a doubtful risk factor or a doubtful aetiology based on several investigations that had confirmed this. Similarly several investigations on prostatitis had confirmed the involvement of HPV and other STI pathogens such as HSV-2. Their continuous screening on routine bases in clinical settings would simply be a right step in the right direction;( as baseline investigation with this regard

5. Conclusions

- The significant level of awareness of HPV (P<0.05) involvement in prostatitis among these cadres of Doctors underscores their choices of tests ( at the expense of HPV screening and even other STI pathogens screening test, such as HSV-2) selection in the Urology clinics due to their over expression of interest in those questions ignored. The significance, as evidenced by calculated and tabulated F value of 5.4 being far higher than the statistic table value. HPV should be routinely and regularly screened for in queried cases of Benign prostate hyperplasia or as prostate cancer manifesting as prostatitis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML