-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Geographic Information System

p-ISSN: 2163-1131 e-ISSN: 2163-114X

2025; 14(1): 14-23

doi:10.5923/j.ajgis.20251401.02

Received: Jul. 21, 2025; Accepted: Aug. 12, 2025; Published: Aug. 18, 2025

Challenges Faced byInterracial Marriages between Chinese and Zimbabweans: Case Study of Chinese Migrants in Zimbabwe

Xiaohua Feng1, Itayi Artwell Mareya2

1Department of Foreign Languages, Hanjiang Normal University, Shiyan, China

2Asia-Africa Teacher Education Research Center, Hanjiang Nomal University, Shiyan, China

Correspondence to: Itayi Artwell Mareya, Asia-Africa Teacher Education Research Center, Hanjiang Nomal University, Shiyan, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the number of Chinese nationals migrating to other countries for business. The increasing interracial marriage disputes caused by cultural differences and communication barriers have led this study to examine the challenges, focusing on cultural taboos with the Chinese and Zimbabweans as the target group. The research investigates the impact of foreign cultures in Zimbabwe. Employing a mixed-methods approach, the study draws upon data collected through online questionnaires. The findings offer valuable insights for travellers, diplomats, business professionals, and anyone intending to visit or reside in Zimbabwe or China.

Keywords: Challenges, Interracial Marriages, Chinese, Zimbabweans

Cite this paper: Xiaohua Feng, Itayi Artwell Mareya, Challenges Faced byInterracial Marriages between Chinese and Zimbabweans: Case Study of Chinese Migrants in Zimbabwe, American Journal of Geographic Information System, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 14-23. doi: 10.5923/j.ajgis.20251401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- China's economic rise has attracted many Chinese business people to flock to other parts of the world, and Zimbabwe is an example, where they partner with local businesses. However, a major hurdle lies in the significant cultural differences between the two peoples. [1] highlights that both Western and Chinese cultures have verbal and non-verbal communication, but each has its own taboos that need understanding.According to the Zimbabwe Investment Development Agency (ZIDA), China has become the largest foreign direct investor in Zimbabwe. Statistics show that currently, Zimbabwe has 427 licensed Chinese companies operating in various economic sectors. Of these, 228 are in the mining sector, while 95 are in the manufacturing sector. The remaining 15 companies are shared among the transport, agriculture, and energy sectors. In 2023 alone, Zimbabwe received about USD 295 million from Chinese investors, while in 2022, Zimbabwe earned about USD 1.3 billion worth of investment from China. These statistics from ZIDA show how challenging it is for Chinese people to understand Zimbabwean culture, and equally for Zimbabwean people to understand Chinese language and culture. Understanding different cultures is key to success in today's interconnected world. The vast differences between Zimbabwe and China, for example, highlight the cultural diversity across the globe. Culture is a complex concept. [2] acknowledges the lack of a single, universally accepted definition. [3], define culture as a system of interconnected values that shapes how people behave, perceive the world, and communicate. Zimbabwean culture has its own unique aspects. [4] discuss the various categories of taboos present. Zimbabwean society as generally peaceful and non-violent. This peaceful nature has fostered friendly relations with neighbouring countries, including China. The passage concludes with a historical debate: [5] challenge the traditional belief that Great Zimbabwe represents the earliest expression of Zimbabwean culture. Chinese cultural stereotypes include ancestral worship exhibited during the Chinese tomb-sweeping day, the Chinese tea culture, paper cutting, colour culture, food culture, and marriages, which are highly revered among all Chinese communities.

2. Research Questions

- • Would you marry a foreigner if there were a chance?• Can you work under the supervision of a foreign boss regardless of his/her nationality?• Is it appropriate in your culture to call someone by his/her color?• Are other cultures more important than others?• Can you call someone with a description of an animal?

3. Literature Review

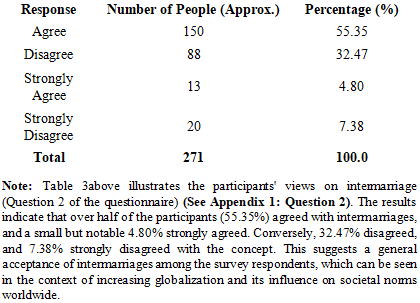

- Marriages in Zimbabwe and China are traditionally recognized as a union between a man and a woman, involving both families [6]. In Zimbabwe, a bride price is paid to the bride's family, but it's seen as an appreciation for raising the bride, not a purchase. Both cultures have pre- and post-marriage customs that influence marital success. With the rise in cross-cultural marriages, some differences have emerged. China's skewed gender ratio, with more men than women, has led to women taking dominance. In Zimbabwe, the female population is higher compared to men. Zimbabwe has 91.26 males per 100 females, while China has a surplus of males with 51.24% compared to 48.74% females. There are many types of marriages in Zimbabwe.New Marriages Law in Zimbabwe. 1. [Marriages Act] [Chapter 5:15].2. [Civil Marriage]. Monogamous marriage (one man, one wife).3. [Registered Customary Law Union]. This allows one potentially polygamous marriage (one man, potentially many wives).4. [Unregistered Customary Law Union] (UCLU). This is a polygamous marriage of one man and many wives.This is contrary to Chinese marriage laws, which only allow one man and one wife, as referred to in Chinese as (一夫一妻 (yì fū yì qī)). According to the new Marriage Act [Chapter 5:17], the age of consent is 18 years. The decline in both marriage and childbearing in China has been attributed to various reasons, such as wealthy women avoiding marriage. Other factors are generally due to the cost of living and the cost of raising a child in China. Despite the practice of bride price, both Zimbabwe and China hold their married women in high regard. Mothers are powerful and respected figures [7]. Similarly, China's high bride price (often exceeding $10,000 USD) reflects the value placed on women (excluding the additional costs of a house and car). Zimbabwean women support the practice of bride price. The passage also touches on Zimbabwe's legal stance on same-sex marriage. The law against same-sex marriage is supported by most Zimbabweans due to cultural values emphasising procreation [8]. However, respect for mothers within Shona culture extends to honouring husbands by their wives [9]. Many Zimbabweans believe in intermarriages. [10] assert that the situation in Zimbabwe is currently marked by intermarriages, mainly of Zimbabwean women to foreigners, particularly to Nigerian and Chinese migrant entrepreneurs who, for the sake of wanting to acquire local citizenship, opt to conveniently offer a high bridal price to get married to local Zimbabwean women. According to [11], intermarriages between Chinese and foreigners are at a record high. The rise is being attributed to the need to do business joint ventures with foreign experts in China. In Zimbabwe, child-rearing is primarily the responsibility of parents. Only in working families or those facing single parenthood do grandparents take on childcare duties [12]. Zimbabwean culture values children as the future, fostering a peaceful environment within families [13]. China presents a contrasting picture. Traditionally, grandparents play a larger role in raising children [14]. Family size also differs, with the average Zimbabwean family having four children, while China's one-child policy (recently abolished) limited families to one child. China is second only to South Korea [15] as far as the cost of child-rearing is concerned. Divorce cases have become a global phenomenon. The high rate of single mothers in Zimbabwe and China has risen over the years. In Zimbabwe, many single mothers usually prefer remarrying, while in China it is the opposite. According to [16], when a man dies and leaves a wife behind, Zimbabwean culture allows the widowed woman to choose from one of her husband’s brothers someone who will ceremonially take her as a wife in order to provide family necessities for the remaining family. This is called in Shona (kugara nhaka) (the inheriting of the wife of a late brother). This does not happen in modern China. [17] et al are of the view that diseases such as HIV and AIDS become more prevalent in single mothers than in married women; therefore, many Zimbabweans support the culture of (kugarwa nhaka). Cultural differences surrounding marriage and childcare can sometimes lead to difficulties in relationships between Zimbabweans and Chinese, potentially contributing to higher rates of separation or divorce in intermarriages between these two groups. Zimbabwean social structures are founded on family totem-stems (mitupo) 图腾 (tú ténɡ). A totem in Zimbabwe is usually derived from names of animals or places. One can only know that he/she is related to another by having a similar totem. Similar family names or surnames do not represent relationships. According to [18], the issue of totems was brought about a long time ago in Zimbabwe as a methodology of conservation of animals, places, and other environmental natural resources from extinction. In Zimbabwe, people who have animal totems mean they should not eat those animals or certain parts of their bodies. This helps in the preservation of animals. Marrying a person with a similar totem is regarded as a taboo in Zimbabwe.The increasing prevalence of interracial marriages in Zimbabwe, particularly those between Chinese nationals and local Zimbabwean women, is significantly influenced by a confluence of factors that warrant careful examination. These key areas include the legal and social implications surrounding divorce and property rights, the complexities of child custody and support arrangements, the processes and motivations related to immigration and residency, and the fundamental recognition of the marital union itself.The legal framework in Zimbabwe concerning divorce and property rights becomes intricate in interracial marriages, especially when assets are located across national borders or when the legal validity and enforceability of prenuptial agreements are questioned in different jurisdictions. Similarly, decisions regarding child custody and support are guided by the principle of the child's best interests under Zimbabwean law. However, the involvement of parents from different cultural backgrounds and the potential for international relocation can introduce significant challenges in ensuring consistent and culturally sensitive child-rearing practices and support arrangements. Furthermore, while marriage to a Zimbabwean citizen can be a pathway to seeking residency, it is crucial to understand that Zimbabwean immigration laws stipulate specific requirements and procedures that foreign nationals must adhere to. Marriage to a local citizen does not automatically confer citizenship.

4. Challenges

- Zimbabwean culture itself is heavily influenced by the west. Many Zimbabwean students arrive in China with limited knowledge of the culture, leading to difficulties at school, shops, and even on the streets. Traditionally, Zimbabweans used art for communication, as evidenced by the rock paintings in the Matopo Hills [19]. Some contemporary Zimbabwean artists, like Masamvu Misheck and Virginia Chihota, have achieved international recognition. China also boasts a long and distinguished artistic tradition. [20] considers the Qing Dynasty art (1680-1795) to be exceptional, while [21] emphasize the continuity of traditional art forms in modern digital art. (Asante K.W. 2000) argues that colonialism stripped Africans of their traditional cultures, including dance, replacing them with Western styles. Zimbabwe is no exception. Research by [22] suggests that the music scene was largely dominated by male voices, reflecting the themes of resistance against colonial rule. This focus on social and political issues wasn't surprising. However, after Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980, the musical landscape began to shift. The emergence of female musicians marked a a significant change. Their voices added a new dimension to Zimbabwean music. Additionally, catchy music jingles became a powerful tool for political campaigns [23]. Groups like the all-female Mbare Chimurenga choir from Harare's Mbare suburbs became a prime example of how music could be used to communicate political messages to the public. This emphasis on music as a tool for social commentary and inspiration aligns with the deep respect China holds for poetry [24]. In both cultures, artistic expression played a crucial role in uniting people and fostering a sense of national identity.Both Zimbabwe and China prioritize healthcare, utilizing traditional, Western, and now blended medical approaches. Research by [25] suggests these cultures view illness similarly, with both traditional and Western medicine having a place. Zimbabwe's colonial past created a diverse healthcare landscape. Some citizens [26] favour traditional methods like rituals, dreams, and herbalism for their perceived effectiveness. The Zimbabwe National Association of Traditional Healers (ZINATHA) regulates traditional practitioners [26] (ibid). Statistics suggest more traditional healers than medical doctors existed in Zimbabwe. [26] defends rituals for providing comfort, citing the COVID-19 pandemic, where traditional herbs were used despite Western predictions of high mortality. Similarly, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, some Zimbabweans initially rejected Western explanations, leading to fatalities [27]. China also boasts a multifaceted healthcare system. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has used natural elements like plants, minerals, and animal products for over 4,000 years. Modern Chinese Medicine (MCM) builds on TCM by transforming traditional herbs into modern medications, exemplified by the successful development of antimalarial drugs (Wang J et al., 2018). Additionally, China incorporates ancestral worship faiths and rituals into its healthcare practices [28].Western medicines are purported to be the answer to human health problems since human civilization, as he attributes the milestones taken in medical progress in Europe. [29] view traditional Chinese medicine as the alternative medical healthcare system in Asia. In Zimbabwe, however, Western medical hospitals play an essential role, running parallel to (ZINATHA).Zimbabweans also believe in spiritual interventions. Shona people also believe in supernatural powers. Spiritual healing is a very rampant activity in Zimbabwe. Zimbabweans are very spiritual people. [30] asserts that the influence of traditional religion and the spirituality of the people in Zimbabwe in issues dealing with healing is very high. From a discussion with some Chinese students, it has been revealed that in ancient times, spiritual healing was also very common, and now it is no longer viewed as a stereotypical Chinese culture. Natural healing is very common in many countries. Some types of sickness or illness may be caused by weather conditions and can also be treated by other different weather conditions as asserted by [31].Zimbabwean culture regards some types of food as medicine. [32] assert that the cost of treatment of diseases in Zimbabwe’s health care system is very high; therefore, many people take preventative measures by eating food that contains medicinal components. [33] allude to [32] ‘s research finding in the rampant usage of wild fruits and vegetables as a prevention against malnutrition.The love of Western food is very high in Zimbabwe, as well as in China. American fast food chains McDonald’s and KFC are very famous in China. According to [34] as alluded to by [35]), the rise in demand for Western food in China is a result of the modernization of food consumption style. [36] asserts that Zimbabwean cultures are very diverse. Drinking taboos are not as many in Zimbabwean culture. Zimbabweans believe in witchcraft and superstition, so sharing a glass of beer or alcohol with a stranger is a taboo. A drinking woman is regarded as weak and an infidel; however, Chinese women and men can both drink alcohol freely.Taboos are social and cultural restrictions that can be related to language, behaviour, or objects. Researchers [37] et al; [38] offer various definitions, highlighting how taboos promote social harmony and address community needs. There are potential consequences of violating taboos. Both China and Zimbabwe have taboos, but the focus differs. China has specific language taboos. For example, terms directly mentioning death might be avoided in favour of euphemisms like "he has gone" [39]. Food taboos are prominent in Zimbabwe. Donkeys, dogs, cats, bats, and snakes are generally not consumed due to cultural beliefs [18] (ibid). In contrast, Chinese food taboos focus more on manners while eating [40]. While some argue they are merely superstitions [41], others see them as a way to preserve the environment [18] (ibid). [42] believe Zimbabwean taboos are ancient traditions with value but acknowledge the difficulty of reviving them in a modern context.Both Zimbabwe and China have traditional dress codes reflecting societal values. Zimbabwean clothing design signifies respect and cultural identity. Similar to [43], who discuss cultural taboos learned through experience, Zimbabwean culture dictates certain clothing norms. For instance, short skirts or dresses might be seen as inappropriate for women. China's approach is more relaxed. While gift-giving etiquette exists (avoiding green hats), there are no strictures on everyday clothing choices. However, funerals call for sombre attire in both cultures: black in Zimbabwe and muted colors in China.The Shona language, like the Chinese language, has very respectful terms for addressing individuals, such as;• 你 (nǐ) English (You) singular• 您(nín) English (You) respect (elders)• 你们 (nǐ mén) English (You) pluralAs far as English is concerned, the pronoun “you” is used to address every kind of person.• (Iwe) English (You) singular• (Imi) English (You) respect • (Imi) English (you plural)[44] describe the Korekore people of Hurungwe in Zimbabwe, who used to decorate their traditional houses with symbolism reflecting their traditional cultural colour values. Chinese people, like Zimbabweans, are also colour sensitive. In China, the colour white (白色, bái sè) acts as a symbol of political reaction, clarity, purity, plainness, and blankness. In China, people wear white at funerals. Chinese people highly respect the red colour for wrapping gifts and during the Spring Festival. In Chinese, the black colour 黑色 (hēi sè) symbolises “dark, sinister, secret, shady, illegal, hiding something away, vilifying, and as a loanword for hacking (computing).” Different cultures have different ideas about beauty. For example, in Zimbabwe, dark skin is often considered beautiful, while in China, it's not typically seen that way. It's also interesting to note how people talk about skin colour. In Zimbabwe, you rarely hear someone call a Chinese person "yellow," but in China, it's common to hear Black people referred to as "black." Regarding gifts, in Shona, an idiom goes like “Kandiro kanoenda kunobva kamwe,” meaning he who gives receives / a good turn deserves another 以德报德 (yǐ dé bàoé), and 善有善报 (shàn yǒu shàn bào) entails how important giving is. People give gifts at weddings, Christmas Day, birthdays, graduations, and various occasions. Zimbabweans give gifts either in money or in kind. At weddings, relatives give livestock, money, or in-kind gifts. It is taboo to give crippled livestock as a gift in Zimbabwean culture. As far as Chinese culture is concerned, one must not give a “clock (钟表, zhōnɡ biǎo), for it may mean wishing a short-lived life. When giving gifts in China, they must be in pairs. A green hat should not be given to a wife or girlfriend as a gift, for this may mean separation. In China, it is taboo to give someone scissors (剪刀, jiǎn dāo) as a gift because it is viewed as wishing a separation. Another forbidden gift in China is an umbrella 雨伞 (yǔ sǎn). A gift of an umbrella in China is viewed as wishing someone bad luck.There are so many words and phrases used by Zimbabweans and Chinese to avoid a clear mentioning of the term "death." [45] argues in his article that Zimbabweans use certain words that avoid the usage of the term "death" but at the same time use words and terms that equally reflect death, as an example:• (Azorora) English is (he/she has rested), while in Chinese they say 他/她休息了 (tā/tā xiū xī le).• (Arara) English is (He/she is asleep), while the Chinese will say 他/她睡了 (tā/tā shuì le).• (Atungamira nzira) English is (he/she has taken the lead). The Chinese will also say 他/她先走了 (tā / tā xiān zǒu le).• (Arova pasi) English is (He/she has gone). In Chinese, they will say 他/她走了 (tā/tā zǒue).All these phrases mentioned above are a sign that no one wants to say, "He/she is dead." (Afa). [46] asserts Zimbabwe has some ritual death taboos, which are very critical. Cremation of dead bodies is still a taboo in Zimbabwe. [47] asserts that the increase in deaths in the early 2000s caused a lot of shortages of burial places in urban areas, resulting in cremation methodology partially used. Most Zimbabweans prefer burying the dead to cremation. In China, cremation is not a taboo. Many Chinese people prefer cremation to burial.The dominant religions in Zimbabwe are Christianity and Catholicism, whilst in China the dominant religious groups are the Islamic groups in west China and a few Christian groups. [48] criticize the theories that categorize people based solely on race or culture. Colonialism introduced foreign religions to Zimbabwe, including Christianity. However, traditional beliefs remain strong, with "Nyatene" or "Musikavanhu" referring to the creator god in Shona (the local language). China also has a strong ancestral belief system. People often perform rituals to honour their ancestors, seeking protection and prosperity. Whilst open to foreign religions, China does not see widespread adoption like in Zimbabwe. Public religious preaching is less common in China compared to Zimbabwe [49].While Shona and Ndebele are Zimbabwe's official languages, English is the medium of instruction in education and employment. [50] highlight the challenge—passing English O-Levels is crucial for both jobs and university enrolment. This disconnect can lead to students struggling with English proficiency. As a result, ‘many Zimbabweans think in their native languages but express themselves in English’. China, in contrast, uses Mandarin as the primary language of instruction. The significant grammatical differences between Shona and Chinese, especially the use of auxiliary words like "de" in Chinese, can create difficulties for Zimbabweans.• My mother is 我的妈妈 (wǒ de mā mā). • 我 (wǒ) means "me/I."• 的 (de) Auxiliary for (of)• 妈妈 (mā mā) mother• In Shona, this sentence is written as follows:• (Amai vangu) My mother.• Amai (mother)• Vangu (My)However, in Chinese, this sentence is written by Shona people as 妈妈的 (mā mā de), which in English and Chinese means "mother's"; this, however, takes on a different meaning from how Shona-speaking people might wish to say "my mother" in Chinese. The sentence itself isn't wrong, but its usage in Chinese is incorrect. The incorrect use of the Chinese auxiliary 的 (de) by Zimbabweans learning Chinese is prevalent. [51] describes, for example, the usage of Chinese degree adverbs as commonly placed before an adjective or verb, whereas in Shona, a degree adverb is commonly placed after an adjective or verb. The errors made between these two languages stem from the influence of the mother tongue. In China, the native language comes first, followed by English. In Zimbabwe, people either speak English first, then a mix of English and Shona, or Shona or Ndebele as the last language. [52] asserts that Japanese, Korean, and Chinese have their own numbers, as is also shown in their sign language for numbers. Chinese people can count all numbers using only ten fingers. When Shona-speaking people are outside of work or school, they speak a mix of Shona and English.• Shona: Handei ku (town). • English: Let’s go to (town).• Meanings: (Handei) plural for (let us go). (Ku) means (to).• Shona: Isa mu (fridge).• English: Put in the (fridge)• Meanings: (Isa) means (put). (Mu) means (inside).It is from this context that shows that communicating with Zimbabweans requires either speaking English or mixing Shona language with English. [53] et al. assert that the term "slang" (俚语, lǐ yǔ) is defined in different and various ways by different ethnic groups. [54] define slang as the language of the internet mainly used by the younger generation. [55] also agrees with [54]'s definition.[56] asserts that since the time of the former President of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, homosexual identities are not tolerated in Zimbabwe [57]. [58] asserts that the Chinese government decriminalized the act of homosexual 20 years ago, but the lack of interaction between LGBT rights groups and the government still leaves a lot to be desired. [59] acknowledges the lack of explicit public policies in China relating to homosexuality, including the rights of gays, lesbians, and transgender. [60] asserts that since 1954, the People's Republic of China's law of equality for all citizens still remains a contest in issues dealing with gender and sexual orientation. [61]shows how students in the United Arab Emirates resisted Western-imposed liberal values which went against their Islamic values. Zimbabweans, like many other non-Western countries globally continue to resist certain Western cultural values which appear to run contrary to Zimbabwean culture.

5. Methodologies

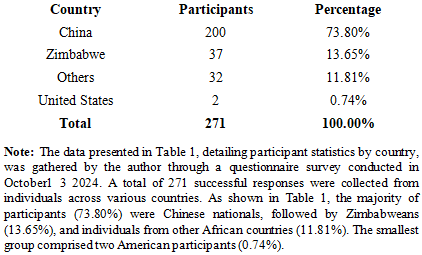

- Quantitative methodology, is useful in the establishment of a correct analysis of the data collected. The authors have used this methodology extensively by way of interviewing participants, their cultural experiences of the two different cultures of Zimbabwe and China, as well as using different literature materials.A questionnaire was distributed to various people of African and Asian origin. Two hundred Chinese nationals, 35 Zimbabweans, 31 from other African countries, and two from the United States.

|

6. Results

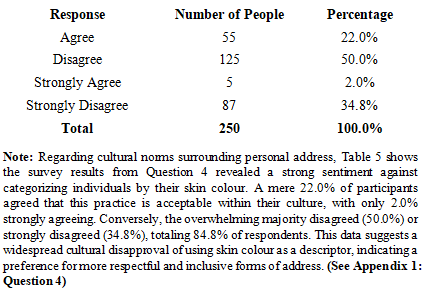

|

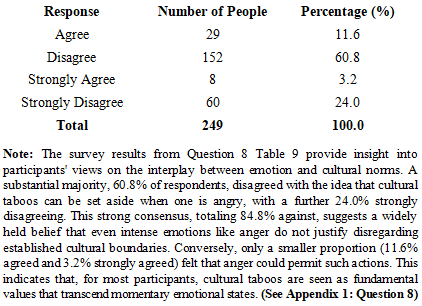

|

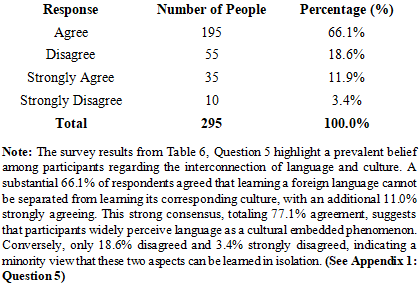

|

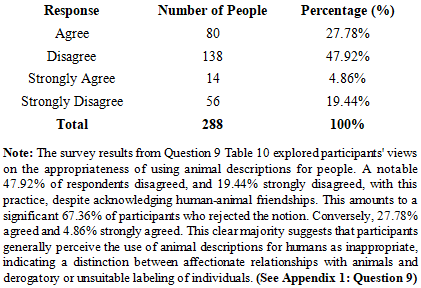

|

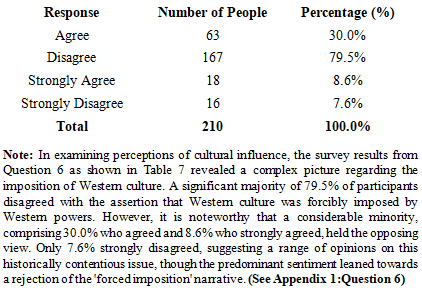

|

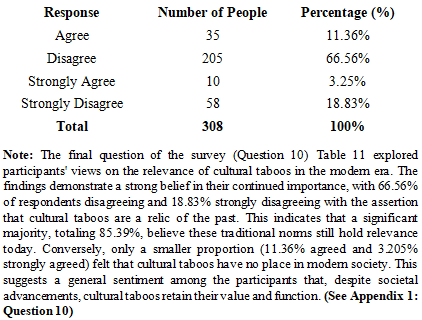

|

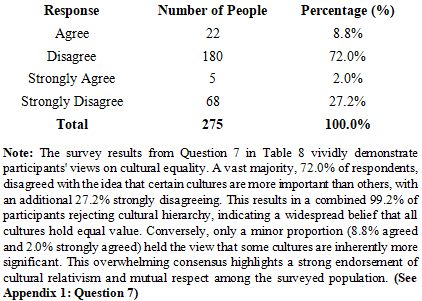

|

|

|

|

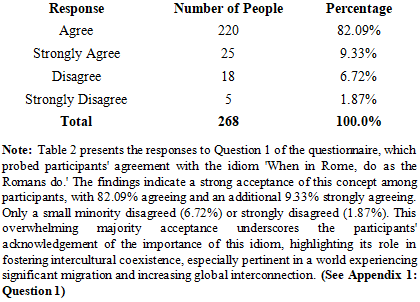

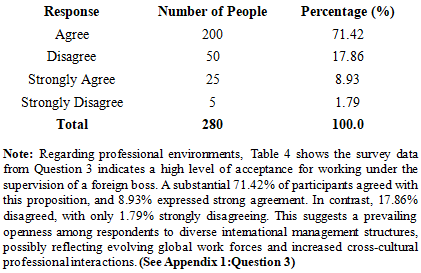

7. Discussion

- Interracial marriages between Asian nationals and Africans in Africa, particularly in Zimbabwe, face significant challenges beyond initial affections. This research indicates profound differences between the two groups, despite some African partners perceiving the Asian as generous. However, a closer examination reveals that many Asian nationals entering these marriages are primarily motivated by the desire for citizenship and the lower bride price demands in Africa compared with their home countries like China.These unions are frequently undermined by substantial cultural, linguistic, and behavioral disparities, leading to high rates of dissolution. Furthermore, a key contrast lies in religious observance: many Africans are deeply religious, while their Asian counterparts tend to be less so. Despite these formidable obstacles, solutions are possible. The concluding recommendations aim to address these challenges and foster more sustainable relationships between the two communities. The results show that some participants in other circumstances chose not to answer certain questions, as shown by some variances in the capturing of data figures. In these circumstances, we disclaim any manipulation of the data results and firmly approve the given data as original and unfiltered.

8. Conclusions

- In conclusion, the impact of interracial marriages between Chinese nationals and Zimbabwean women in Zimbabwe is shaped by a complex interplay of legal, economic, and social factors. Understanding the nuances within divorce and property rights, child custody and support, immigration and residency processes, and the recognition of marriages is essential for navigating the challenges and ensuring the equitable treatment and well-being of all individuals involved in these increasingly common unions. Open dialogue, cultural sensitivity, and a clear understanding of the relevant legal frameworks are crucial for addressing the perspectives and potential vulnerabilities of all parties involved. Increased economic interaction has linked Zimbabwe and China, marked by Chinese investment having flowed into Zimbabwe and Zimbabwean students having been drawn to study in China. Significant cultural differences, language barriers, and differing taboos have created communication challenges and potential conflict.

CRediT

- Credit to my co-author, Itayi Artwell Mareya, for his valuable contributions to this research, particularly in conceptualization, methodology, resources, validation, and the original draft. I also thank Zimbabwean students in China and the students at Hanjiang Normal University for their participation in the survey.

Funding

- This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

- The data used to support the findings of this study has already been made available

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statement

- The authors’ research type did not suit the criteria to produce an ethical statement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML