-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Geographic Information System

p-ISSN: 2163-1131 e-ISSN: 2163-114X

2017; 6(4): 129-140

doi:10.5923/j.ajgis.20170604.01

GIS Implementation for Health Management in Malawi: Opportunities to Share Knowledge between Implementers and Users

Patrick Albert Chikumba1, 2, Gloria Chisakasa2

1Department of Informatics, University of Oslo, Norway

2Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of Malawi – The Polytechnic, Malawi

Correspondence to: Patrick Albert Chikumba, Department of Informatics, University of Oslo, Norway.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Knowledge is recognized as the most important resource in organisations, including public organisations, and its management is considered critical to organisational success. In organisations, knowledge and skills of employees in using computer systems have become a critical factor for successful use of information and communication technologies (ICT). Even the literature of Geographic Information System (GIS) in developing countries has discussed several challenges, including lack of knowledge and skills, in the implementation and use of GIS. The literature further recommends knowledge sharing and collaboration as some means of acquiring and accumulating knowledge. The argument is that knowledge multiplies when it is shared effectively. The concept of knowledge has been discussed in information system (IS) and organisation literature with few studies on knowledge in public sector as compared to those in private sector. However, much is written about ‘why’ managing knowledge and little on ‘how’ knowledge is identified, captured, shared and used within organisations. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore opportunities for sharing knowledge between implementers and users in the public health sector during the implementation of an information system using the case of DHIS2 GIS for health management in Malawi. This is the case study and it has employed qualitative interpretive methods with the aim of understanding social and natural settings of GIS implementers and users and their knowledge sharing practices. The study has used multiple choices of data sources. It has been observed that interactions between implementers and users are mainly through work teams, training, emails and manuals. There is little utilization of technology-based systems. The study recommends to CMED to explore the potential benefits of technology in knowledge creation, sharing and use. Literature argues that social computer applications assist greatly in reducing formal communication barriers and open new possibilities for organisations to boost knowledge creation and sharing.

Keywords: DHIS2 GIS, GIS implementation, Individual knowledge, Opportunities to share knowledge

Cite this paper: Patrick Albert Chikumba, Gloria Chisakasa, GIS Implementation for Health Management in Malawi: Opportunities to Share Knowledge between Implementers and Users, American Journal of Geographic Information System, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2017, pp. 129-140. doi: 10.5923/j.ajgis.20170604.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- For Geographic Information System (GIS) to survive in any context as any other information systems (IS), it needs adequate resources including people with required knowledge and skills. Campbell and Shin [1] emphasize that GIS is a tool, which requires people who have certain knowledge in order to use and apply GIS properly to solve problems. Even Longley, Goodchild, Maguire and Rhind [2] argue that GIS technology is of limited value without people who manage and develop plans for applying it to real world problems. People are the most important part of GIS who overcome shortcoming of other elements such as data, technology and procedures [3]. According to Munkvold [4], in organisations, knowledge and skills of employees in using computer systems have become a critical factor for successful use of information technology (IT). These people include users, implementers, designers, and developers. In this paper, the interest is on users and implementers of a GIS application.GIS literature in developing countries has discussed several challenges including lack of knowledge and skills. One way of improving knowledge and skills is through knowledge sharing. Knowledge, as an asset, needs to be acquired and accumulated [5], for example, through sharing because knowledge multiplies when it is shared effectively [6]. Knowledge sharing occurs at various organisational levels (such as individual, group, department, division and organisation), through informal and formal approaches, and two main delivery methods: tacit and explicit [7]. In this paper, individual knowledge sharing is emphasized. The understanding is that without individuals knowledge cannot be created, and unless individual knowledge is shared, knowledge is likely to have limited impact on organisational effectiveness [8]. Kim and Lee [9] point out that knowledge sharing should involve dissemination of individual work-related experiences and collaborations among individuals, subsystems and organisations. In the context of GIS, this paper focuses on IT knowledge sharing between implementers and users. The authors argue that proper sharing of IT knowledge between implementers and users is crucial in realizing intended benefits, particularly in developing countries. López, Peón and Ordás [10] define IT knowledge as the extent to which the organisation possesses a body of technical knowledge about elements such as computer systems. They define technical knowledge as the set of principles and techniques that are useful to bring about change towards desired ends. Specifically, in this paper, the interest is on ‘GIS knowledge’, which is defined as the set of principles and techniques that are useful in GIS implementation. The paper takes GIS implementation as an ongoing process of decision making, through which users become aware of, adopt, and use GIS [11].The concept of knowledge has been discussed extensively in information system and organisation literature. However, much is written about ‘why’ managing knowledge is important to organisations and little on ‘how’ knowledge is identified, captured, shared, and used within organisations [8]. On the other hand, few studies have focused on knowledge sharing in the public sector as compared to those studies in the private sector [12]. As a contribution to ‘how’ (processes of), this paper discusses existing opportunities to share ‘GIS knowledge’ between implementers and users in DHIS2 GIS implementation in Malawi. District Health Information Software (DHIS) is a tool for collection, validation, analysis and presentation of aggregated statistical data. DHIS version 2 (www.dhis2.org) is a modular web-based software package and has several modules including GIS that provides spatial presentation of health data and indicators by organisation units through linking spatial and non-spatial data in one database. In 2012, Ministry of Health (MoH) in Malawi started using DHIS2 as an integrated central platform for health programs and services in its national health management information system (HMIS). Since MoH lacks technical capacity, DHIS2 is technically supported through DHIS2 team that consists of members from collaborating partners.The paper discusses how some processes in GIS implementation for health management can facilitate the sharing of knowledge. Therefore, the research questions are: How do implementers interact with users in GIS implementation? How can interactions between implementers and users affect individual knowledge sharing? These research questions have been answered through the analysis of empirical material and guided by the model of knowledge sharing between individuals in organisations proposed by Ipe [8]. The model includes four factors: the nature of knowledge, the motivation to share, the opportunities to share, and the culture of the work environment. The factors have been discussed in detail in the next section. In this case study, the emphasis is on the opportunities to share knowledge. The rest of the paper contains related literature on individual knowledge sharing, research methodology, GIS initiatives, discussions on the opportunities to share knowledge and conclusions.

2. Related Literature

- It has been observed that there are significant changes on how public organisations are being managed; moving from a traditional, bureaucratic approach to a more managerial one [12]. In this context, knowledge is recognized as one of the most important resource [8, 13]. Hence, pubic organisations are treated as knowledge-based organisations [12] and there is a need for processes that facilitate the creation, sharing, and leveraging of knowledge [8].

2.1. Individual Knowledge Sharing

- Knowledge can be taken as a fluid mix of framed experiences, contextual information, values, and expert insight that provide a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information [9]. Knowledge can also be understood as information processed by individuals relevant for the performance of individuals, teams, and organisations [12]. As mentioned earlier, this paper focuses on individual knowledge, since knowledge is actually created, shared, and used by people in organisations [8]. Hence, this section discusses the individual knowledge sharing. Ahmad, Sharom and Abdullah [6] argue that the ability to share knowledge among individuals represents possibly the greatest strategic advantage an organisation can achieve. For example, knowledge sharing represents the means for continuous performance improvements for a public organisation.There are three types of individual knowledge: ‘know-how’, ‘know-what’, and dispositional knowledge [8]. Ipe [8] states that ‘know-how’ includes experience-based knowledge that is subjective and tacit; ‘know-what’ includes task-related knowledge that is objective in nature; whereas dispositional knowledge can be defined as personal knowledge that includes talents, aptitude, and abilities. Individual knowledge resides in the brains and bodily skills of the individual which can be applied independently to specific types of task or problem [13]. In addition, this type of knowledge is “transferable, moving with the person, giving rise to potential problems of retention and accumulation” [13]. It is important for an organisation to facilitate the sharing of knowledge, otherwise it is likely to lose some knowledge when individual employees leave [8]. Ipe [8] further argues that unless there are opportunities for individuals to share knowledge in the organisation, the full extent of their knowledge may not be realised and utilised. It is expected that knowledge held by an individual is converted into a form that can be understood, absorbed, and used by other individuals [8]. Knowledge sharing refers to the provision of knowledge to help and collaborate with others to solve problems, develop new ideas, or implement policies or procedures [12]. When individuals share their knowledge and build on the knowledge of others, leveraging knowledge is possible [8]. Knowledge sharing is typically voluntary [12]. It contributes to knowledge distribution and the process of sharing may result in acquisition of knowledge by other individuals within the organisation [8]. Furthermore, knowledge sharing is a process of exchanging and processing knowledge in a way that knowledge of one unit can be integrated and used in another unit [14]. Knowledge sharing involves a relationship between at least two parties (one that possesses the knowledge and the other that acquires it), which needs some conscious action on the part of the individual who possesses the knowledge [8].

2.2. Ipe’s Model of Individual Knowledge Sharing

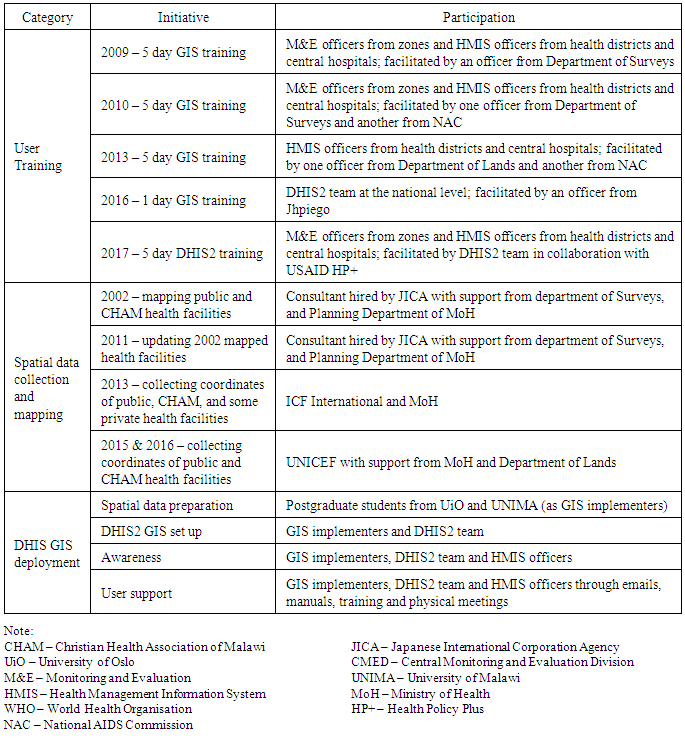

- Various factors influence knowledge sharing. In this paper, four major factors suggested by Ipe [8] have been applied: the nature of knowledge, the motivation to share, the opportunities to share, and the culture of the work environment. The model presented in Figure 1 was proposed based on existing literature in the area of knowledge sharing. By its nature, knowledge exists in tacit and explicit forms and their difference is related to the ease and effectiveness of sharing [8]. In order to share these forms of knowledge, opportunities should exist in the organisation. However, opportunities alone, without personal motivation, cannot bring much influence on the knowledge sharing. According to Ipe [8] these three factors are embedded within the culture of the work environment. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among the four factors.

| Figure 1. A Model of Knowledge Sharing Between Individuals in Organisations (Source: [8]) |

2.2.1. Nature of Knowledge

- As stated earlier, there are two forms of knowledge: tacit and explicit. However, Lam [13] argue that although it is possible to distinguish conceptually between these two forms of knowledge, they are not separate and discrete in practice. Tacitness, explicitness, and value of knowledge influence knowledge sharing within organisations [8]. New knowledge is usually generated through the dynamic interactions and combination of tacit and explicit knowledge [13]. Ipe [8] argues that tacit and explicit knowledge differ in three major areas: (i) codifiability and mechanisms for transfer, (ii) methods for acquisition and accumulation, and (iii) the potential to be collected and distributed.According to its nature, tacit knowledge cannot easily be codified and communicated, understood, or used without the knower [8, 13]. In other ways, this type of knowledge is difficult to transfer [12]. Individual tacit knowledge is acquired through personal experience [8] which is ‘learning-by-doing’ [13]. Tacit knowledge is experience-based that can only be revealed through practice in a particular context, in which close involvement or interaction and cooperation of the knowing subject are required for the realization of its full potential [13]. On the other hand, explicit knowledge can be aggregated at a single location, stored in objective forms and appropriated without the participation of knowers [8, 13]. It is generated through logical deduction and acquired by formal study [13]. The value attributed to tacit or explicit knowledge has a significant impact on whether and how individuals share such knowledge [8]. Particularly, when the knowledge is perceived as a valuable commodity by individuals who possess it, knowledge sharing becomes a process mediated by decisions about what knowledge to share, when to share, and who to share with [8].

2.2.2. Motivation to Share

- Strong personal motivation is likely to influence individuals to share knowledge. Ipe [8] categorizes motivational factors that influence individual knowledge sharing into two: internal factors (e.g. the perceived power attached to knowledge and reciprocity resulting from sharing) and external factors (e.g. relationship with the recipient and rewards for sharing). According to Ipe [8], the notion of power around knowledge can be created when there is the increasing importance given to knowledge and the increasing value attributed to individuals who possess the right kind of knowledge. But this may result in knowledge hoarding instead of knowledge sharing. However, knowledge sharing can be facilitated by the mutual give-and-take of knowledge if individuals see that the value-add to them depends on the extent to which they share knowledge with others [8]. Since knowledge sharing is between individuals, the knower’s relationship with recipients is crucial and it can be influenced by trust, and power and status of the recipient. Even though the distribution of power matters in organisations, trust is more important because, for example, decisions to exchange knowledge under certain conditions are based on trust [8]. Ipe [8] argues that individuals with low status and power in an organisation tend to direct information to those with more status and power whereas individuals with more status and power tend to direct information more towards their peers than towards those with low status and power. Within an organisation, chances of members to share knowledge are positively related to rewards and negatively related to penalties being expected from knowledge sharing [8]. However, in long run, tangible rewards alone cannot help to sustain the knowledge sharing, unless its activities help employees meet their own goals [8].

2.2.3. Opportunities to Share

- Opportunities to share individual knowledge can be grouped into two: formal and informal opportunities. Formal opportunities include training programs, structured work teams, and technology-based systems that are designed to explicitly acquire and disseminate knowledge and they are referred to as ‘formal interactions’ or ‘purposive learning channels’ [8]. From the coordination perspective, Willem and Buelens [14] group formal opportunities further into formal systems and lateral coordination. Willem and Buelens [14] state that formal systems are any kind of coordination that is planned and formally established, such as formal procedures, rules, manuals, and formal processes, but they have limited potential for enhancing knowledge sharing although they are considered to have a low cost. Lateral coordination is also formal but not planned in advance, for example, teamwork, liaison roles, task groups, and mutual adjustments which may be more flexible and timely knowledge sharing than the formal system [14]. Generally, formal opportunities are able to connect a large number of individuals and allow for the speedy dissemination of shared knowledge, especially through electronic networks and other technology-based systems [8].On the other hand, according to Ipe [8], informal opportunities include personal relationships and social networks that facilitate learning and sharing of knowledge and even help individuals develop respect and friendship that may influence their behaviour. Willem and Buelens [14] argue that in public organisations, there is a need for voluntary, natural, and spontaneous personal networks with high levels of personal connectivity and social identity and low levels of management control to allow knowledge sharing. Literature has shown that most amount of knowledge is shared in informal settings, i.e. through the relational learning channels [8].

2.2.4. Culture of Work Environment

- Literature recognizes organisational culture as a major barrier to effective knowledge creation, sharing, and use [8]. The culture of a unit and/or an organisation at large can influence three major factors discussed above. Ipe [8] suggests certain aspects of organisational culture that influence knowledge sharing, which state that culture (i) shapes assumptions about which knowledge is important; (ii) controls relationships between different levels of knowledge (i.e. organisational, group, and individual); (iii) creates the context for social interaction; (iv) determines norms regarding the distribution of knowledge; and (v) suggests what (not) to do regarding knowledge processing and communication in an organisation.

3. Research Methodology

- This case study was conducted in Malawi health sector between June 2015 and June 2017 at national and district levels. Malawi is a landlocked country in southeast Africa and it borders with Tanzania to the northeast, Zambia to the northwest, and Mozambique to the east, south and west. The government of Malawi, through Ministry of Health (MoH), is the main provider of health care services. The health system has five levels of management: nation, zone, district, facility and community. MoH, Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MoLGRD) and other government agencies have over 50 percent of health facilities (referred to as public health facilities) and the rest are under administration of Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) and private practitioners. As one way of strengthening its HMIS, MoH established Central Monitoring and Evaluation Division (CMED) under Department of Planning and Policy Development with the overall objective of continuously collecting, analysing and using data to monitor and evaluate progress towards achieving goals and objectives of the health sector. MoH through CMED is working with various stakeholders, both local and international, in setting-up and supporting electronic health information systems and one of its projects is the implementation of GIS for health management.In this research, qualitative and interpretive methods were applied with the aim of understanding social and natural settings of DHIS2 GIS implementers and users at national and district levels and their knowledge sharing practices. This qualitative research has guided the authors to understand different ways of how participants look at reality [15]. The aim of interpretive research in this case study was to interpret the context of DHIS2 GIS and how the system has influenced and been influenced by the context [16]. Data was collected primarily through participant observations in the whole study period when DHIS2 GIS was being deployed. Observations were done at the national level in order to understand the context in which implementers and users work. The implementation of DHIS2 GIS was carried out at the national level. The authors were part of DHIS2 team as the implementers of DHIS2 GIS. DHIS2 team is coordinated by CMED and composes of members from HISP Malawi, MoH-IT Unit, Jhpiego, Baobab Health Trust, and University of Malawi (UNIMA). Participant observations have permitted the authors evaluating whether there are unintended and unanticipated consequences that need attention.Since some GIS implementation activities were executed before June 2015 specifically GIS user training and spatial data collection, semi-structured interviews and document analysis were applied to assess how these activities were carried out and their contributions towards knowledge sharing. Fifteen separate interviews were conducted. Each interview took up to 45 minutes and at premises of individual participants. At the national level, semi-structured interviews were conducted with three officers from CMED and two members of DHIS2 team. At the district level, interviews were conducted with four HMIS officers and six health program coordinators in two health districts of Blantyre and Mchinji, and one more HMIS officer of a central hospital. The interviews focused on efforts on GIS implementation including internal capacity and support that CMED has been receiving from collaborating partners. Document analysis involved written data sources including minutes of meetings, reports, forms, policies and strategies, emails and job descriptions. There are twenty-nine health districts and four central hospitals in which there are HMIS officers who provide technical support to health managers and coordinators, and other stakeholders. Hence, in order to get a broad view on GIS implementation activities and knowledge sharing, a questionnaire was designed and sent electronically to HMIS officers in health districts and central hospitals. The purpose was to gather data on their length of service, main activities they perform on DHIS2, how they get experiences on GIS, and their expectations on DHIS2 GIS.In this case study, the thematic analysis approach was adopted to identify, analyse, and report patterns or themes within data [17]. Data was analysed by classification according to the major themes, with the guidance of the conceptual model of individual knowledge sharing presented in the previous section.

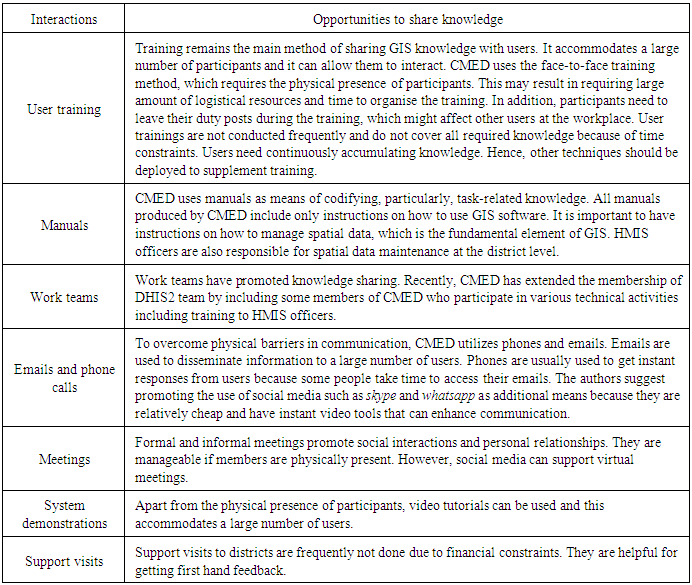

4. GIS Initiatives from 2002 to 2017

- Several GIS initiatives have been taking place since 2002. In this paper, only those initiatives that seem to facilitate knowledge sharing are considered. Table 1 summarizes GIS initiatives from 2002 to 2017, which are further elaborated in this section. MoH carried out most activities in collaboration with its development partners and other government agencies.

|

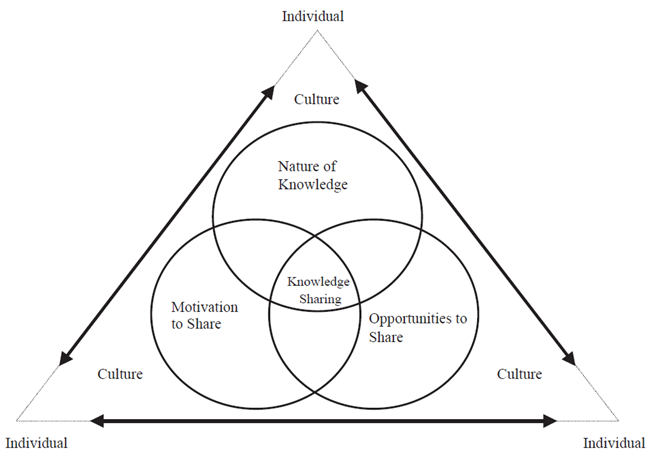

4.1. Champion, Implementers and Users

- In literature of GIS in developing countries, identifying a ‘champion’ within the organisation is considered as the most significant step a government agency can take to implement effective GIS [18]. According to Meaden [19] “a champion is usually the person within the organisation who initially has an idea of GIS use and adoption and who in some way pursues this and fosters its growth and development within the organisation.” Some activities that a champion performs include user awareness and involvement, senior management awareness and support, implementation planning and interacting with external parties [20]. In Malawi, CMED has recognized the potential of GIS in health management and promoted its use. CMED has been working with users at both national and district levels, senior management (e.g. health managers), and collaborating partners in various GIS implementation activities such as mapping of health facilities, user training, spatial data collection and deployment of DHIS2 GIS (see Table 1). In this context, CMED is taken as the ‘champion’, which is not necessarily an individual person but a group of people providing “the force that drives adoption and implementation of GIS.” [18]. Champions are not necessarily experts in GIS but they understand potential benefits and capabilities of GIS. Hence, organisations need to hire services of GIS experts from somewhere else. For example, in the study by Convey and Dewey [18], they found that GIS implementation in Pennsylvania Local Governments was championed by township managers but the actual work was managed by the hired GIS engineers who served as the GIS managers. Similarly, in this case study, it has been observed that people from collaborating partners were the ones managing the GIS implementation activities because of their GIS expertise. In the case of DHIS2 GIS, two postgraduate students from University of Malawi and University of Oslo managed the exercise, who are referred to as implementers in this paper. Users of DHIS2 are from district and national levels who are either experts or novices. Expert users are individuals who are familiar and experienced with the system whereas novices are users who are not familiar with the system and they need support from expert users or through other means [21]. At the national level, members of DHIS2 team are expert users of DHIS2 GIS after getting required knowledge from the implementers and hence, they are able to provide support to other stakeholders, such as health managers, who are novices. Similarly, at the district level HMIS officers are expert users providing support to health program coordinators and other stakeholders who are novices. HMIS officers get the support from expert users and implementers at the national level. Throughout the period of deploying DHIS2 GIS, the implementers have been working with DHIS2 team and provide support to HMIS officers when and where necessary. Figure 2 illustrates interactions between implementers and users within the level and between levels.

| Figure 2. Interactions between Implementers and Users |

4.2. GIS User Training

- CMED has put much effort on HMIS officers at the district level in terms of developing GIS knowledge through training. As shown in Table 1, the first GIS training for capacity building was conducted in 2009 and participants were HMIS officers and M&E officers. HMIS officers provide technical support at the district level, particularly to DHIS2 users, under the coordination of M&E officers at the zonal level and support from DHIS2 team at the national level. A year later, the officers attended the training in spatial data collection using global positioning system (GPS) in preparation for collecting coordinates of health facilities in their respective health districts. In 2013, HMIS officers were also trained in GIS application in health management. In all the training sessions, trainers were from other government agencies. CMED recognises the GIS potential in these agencies as commented by one participant: “The departments of Surveys and Lands have vast experience in GIS since they have been using it for a long time in surveys and land management … for NAC, they have experiences in both domains of health and GIS technology.”During the deployment of DHIS2 GIS, one-day training session was conducted in 2016. The officer from Jhpiego, which has been using DHIS2 GIS for some years at the institutional level, facilitated this training. After the rollout of ‘reconfigured’ DHIS2 in 2017, DHIS2 team trained M&E officers from zones and HMIS officers from health districts and central hospitals on the new version of DHIS2 including GIS in collaboration with USAID HP+.

4.3. Spatial Data Collection and Mapping

- Like in user training, during spatial data collection and mapping activities MoH depended on the GIS expertise from collaborating partners. The consultant hired by JICA and officers from Department of Surveys carried out exercises of mapping health facilities in 2002 and 2011. Even in 2013, 2015 and 2016 coordinates of health facilities were collected with the technical support from other organisations.In 2013, ICF International and MoH collaboratively collected coordinates of 997 public health facilities from central hospitals down to health posts and some private hospitals and clinics. This exercise was done as part of service provision assessment (SPA) survey. SPA took at large-scale a detailed look at status of health facilities, particularly availability and quality of services. After being trained in using global positioning systems (GPS), health personnel who were involved in the survey collected the coordinates. In this exercise, HMIS officers were not involved, although by this time they had already been trained in GIS and spatial data collection. “In this exercise, we felt that HMIS officers would not have much work to do … instead we trained medical assistants and nurses in collection of coordinates using GPS while assessing health facilities …” – one participant emphasized.Even in the exercise of spatial data collection in 2015 and 2016, HMIS officers were not part of the team. Instead, officers from the department of Lands were hired as GIS experts. In this exercise, UNICEF collected coordinates of 9498 public health facilities including village and outreach clinics across the country with the support from health personnel including health program coordinators and community health workers. “The role of HMIS officers was just providing the latest lists of health facilities in their respective health districts for the teams to use.” – another participant commented.

4.4. DHIS2 GIS Deployment

- CMED decided to adopt DHIS2 GIS at the district and national levels since it has already invested in DHIS2 as its national integrated platform for health management information system (HMIS). The setup of DHIS2 GIS is basically a matter of populating coordinates of organisation units in the database and immediately maps are available in the GIS module [22]. However, the exercise was not easy as it sounds. Hence, a number of activities were performed from 2015 to early 2017, which included the configuration of DHIS2 GIS, acquisition and accumulation of spatial data of health facilities and administrative boundaries, pre-processing of spatial data, and uploading coordinates into the database. In addition, one day training session was organised to equip DHIS2 team with basic knowledge of GIS, since it was the first time for the team to carry out such exercise and members had inadequate GIS knowledge. As the part of awareness, HMIS officers in health districts were communicated through emails instructing them to verify if health facilities in their respective districts were accessible in DHIS2 GIS. The implementers coordinated this process. The implementers visited HMIS officers in two health districts to demonstrate the system and get their feedback before it was rolled out. Thereafter, apart from the training, DHIS2 team developed and distributed a user manual to HMIS officers and other stakeholders to guide them when using DHIS2 GIS.

4.5. HMIS Officers and GIS

- As mentioned in the research methodology, the questionnaire was sent electronically to thirty-one HMIS officers across the country and nineteen of them responded. Out of the nineteen respondents, seven have served at this post for not more than five years; four have served between six and ten years; and eight have served for over ten years. Ten out of the nineteen respondents have experiences of using GIS and three indicated that they have over ten years’ experience in GIS use. In the case of GIS training, eleven respondents attended various training sessions in different years. In the case of GIS use and training, few respondents have used the system without attending any GIS training while others have attended training but have not used GIS.The questionnaire had also the open question to comment on GIS use and expectations. Below are some responses, which are in two categories: use of and knowledge about GIS.

4.5.1. Comments on Use of DHIS2 GIS

- • “Presentations have been made simple. Tables and graphs that have been used all along will now be supplemented with maps.”• “We expect to map the disease burden in facilities, services performance and staff allocation and many other activities.”• “To map a population that lives within 5km radius.”• “To include district maps in our analysis.”• “It will assist in data presentation such that it will enable visual comparisons of performance between facilities.”• “Work made simple as many data users are asking for updated maps and distances from one point to another. This will assist planners to know which facilities can easily be reached by the community and which ones are close to each other.”• “GIS is a welcome development for HMIS officers. I have been asked on several occasions to produce maps of my district from many important people like my supervisors, politicians, students, managers and many more. It was a big challenge. I was using maps sometimes not relevant to the theme of the task.”• “So thankful for your good plans of introducing this important module (GIS) in DHIS2. This will ease the burden of hunting maps from other sources to include in our reports; it will speed up report writing process.”

4.5.2. Comments on Knowledge about DHIS2 GIS

- • “To be trained in the use of GIS in terms of data viewing, geographical setting of health facilities of my district and the data elements that GIS shows in terms of performance as per selected period.”• “To equip us with knowledge and skills so we can train others (e.g. program coordinators) how to use GIS at district level.”• “Training should be intensive that will have all aspects of creating facility maps and adding layers and more parameters of GIS.”• “GIS is good but the only set back is that I have little knowledge on how to come up with district map and even how to make facility boundaries.”• “There is a need for in-depth training for better implementation.”• “For effective use of DHIS2 GIS, orientation to officers and health workers is needed.”

5. Opportunities to Share Knowledge

- In Malawi, as observed in other developing countries [23, 24], there is no adequate GIS expertise particularly in the health sector and it is difficult to recruit people with all required GIS knowledge and skills. Alternatively, CMED has been developing such resources internally at the district level. The observation is that GIS knowledge is available at the national level through collaboration and there is a need for sharing such knowledge with other stakeholders at national and district levels. In this regard, this paper discusses how existing opportunities can be leveraged for sharing individual knowledge in GIS implementation for health management in Malawi. The emphasis is on learning-by-doing, collaboration, and technology-based systems.

5.1. Collaboration and Work Teams

- Literature of GIS implementation in developing countries emphasizes the importance of collaboration [11, 25, 26]. This case study has focused on collaboration between organisations, which is taken as when two or more organisations in a problem domain engage in an interactive process to act on issues related to that domain using shared rules, norms, and structures and it is not influenced by market or hierarchical mechanisms of control [27, 28]. CMED has been collaborating with some organisations that have experiences in GIS. According to the findings, majority of GIS implementation activities were collaboratively carried out. In the case of acquisition and accumulation of knowledge, collaboration has allowed CMED to build work teams of both experienced and non-experienced GIS users, leading to individual knowledge sharing, particularly at the national level. As Sirmon, Hitt and Ireland [29] point out, if an organisation does not have the required knowledge, it might form strategic alliances with those having the desired knowledge. This can be valuable to the organisation for learning new knowledge. Taking example of DHIS2 GIS implementation, the implementers with vast knowledge of GIS worked with DHIS2 team for two years and this has resulted in sharing the desired GIS knowledge with members of the team. In this context, collaboration has facilitated the sharing of knowledge through learning-by-doing [13]. As evidence, in 2017 DHIS2 team trained HMIS officers in DHIS2 GIS and developed the user reference manual.At the district level, collaboration also exists. Health programs collaborate with, for example, non-government organisations (NGOs) in various activities and sometimes these collaborating partners bring technologies to support their work, which require support from HMIS officers. Since HMIS officers are technical experts at the district level, they also provide support to other systems apart from DHIS2. Even some HMIS officers have gained GIS knowledge through existing collaborations at the district level.However, if the work environment is not conducive enough for knowledge sharing, collaboration cannot be seen as effective means. In collaboration, a focal organisation depends on individuals with the desired knowledge. This type of knowledge moves with the person and hence it is difficult to retain and accumulate [13] and it can be lost when the individual leaves the organisation [8]. To reduce the impact of this challenge, apart from work teams CMED uses training programs and development of reference manuals as other mechanisms for sharing knowledge. Through these mechanisms, CMED is able to reach a large number of users at the district level.

5.2. User Training and Manuals

- As shown in Table 1, CMED uses training as the main means of sharing knowledge with HMIS officers at the district level. Due to the decentralization in public sector in Malawi, HMIS officers have been providing technical support at the district level [30]. It is a recommended decision to invest in HMIS officers because when building the capacity local teams should be equipped with understanding of both application domain and technology being implemented; this contributes towards the sustainability of the system [31]. HMIS officers have vast experience in health information management due to their length of service of 15+ years’ experience for some officers. Providing GIS knowledge can equip them with both understanding of the health information management (as the application domain) and GIS (as the technical domain) which might contribute towards the sustainability of DHIS2 GIS for health management. In all trainings, participants were provided with instructional manuals for further reference.It has been observed that HMIS officers were not given a conducive environment to practice what they learnt so that they could improve their knowledge through learning-by-doing. It was expected that HMIS officers would be part of the GIS implementation activities such as spatial data collection and deployment of DHIS2 GIS because by then they had been trained in GIS, but it was not the case. It could be much better for HMIS officers to participate in some GIS implementation activities so that they could share knowledge with experienced individuals and put the knowledge into practice. The inclusion of these officers could also create opportunities of building social networks and relationships with experienced individuals, which may result in the continuity of knowledge sharing.Another observation is that HMIS officers were trained in many occasions since 2009 but there was no any GIS application for them to put their knowledge into use, which resulted in forgetting what was learned. One HMIS officer commented: “I was trained but I have forgotten everything due to not using the knowledge.” Since CMED has implemented DHIS2 GIS, it is expected as usual practice that HMIS officers would provide technical support at the district level. Hence, there was the user training on the new instance of DHIS2 in 2017 as means of equipping HMIS officers with required knowledge.

5.3. Culture of Work Environment

- The culture of the work environment may influence the absence of HMIS officers in the GIS implementation activities. Most GIS implementation activities have been carried out at the national level and therefore, it was difficult to include HMIS officers in work teams due to the nature of work. For instance, there are over 50 HMIS officers from 29 health districts and five central hospitals and hence, it was not possible to include all of them in, for example, the spatial data collection or deployment of DHIS2 GIS. These activities require very few skilled persons.On the other hand, the culture of the work environment has been promoting knowledge sharing through informal interactions at both national and district levels, which is in line with the understanding of Ipe [8] that the culture creates the context for social interactions. Most knowledge in an organisation is tacit in nature, which can easily be shared through dynamic interactions and collaborations [8, 13, 14]. For instance, at the district level, HMIS officers work with health program coordinators, health personnel and other stakeholders in the provision of technical support through which there is an opportunity to share technical knowledge between expert users and novices. Even at the national level, DHIS2 team provides the technical support to CMED, health program managers and other stakeholders. Some HMIS officers have learned information technology (IT) on the job through social interactions. “My background is statistics. I have not been trained in IT before but I am able to support users on various systems because I have learned through interactions with them.” – one HMIS officer emphasised. Utilisation of technologies can easily promote such social interactions.

5.4. Technology-based Systems

- Currently, most interactions that promote individual knowledge sharing at national and district levels require the physical presence of individuals. This case study has revealed that CMED does not utilise existing technologies that can promote knowledge sharing particularly at the district level, except emails and phones. From the findings, interactions between HMIS officers from different health district are mainly in existence when there is an inter-district meeting or training. Hence, it is hard for HMIS officers to share technical knowledge due to physical distances. This gap can be narrowed using technology. Technologies are now potential for enhancing knowledge sharing in organisations by networking individuals. CMED considers emails and phones as other avenues for knowledge sharing. During the implementation of DHIS2 GIS, emails have enabled implementers and expert users at the national level to communicate with a large number of expert users at the district level as quickly as possible. Ipe [8] observes that formal interactions, particularly technology-based systems, allow connection to a large number of individuals and quick dissemination of shared knowledge. However, the communication through emails is usually personalised and in the case of CMED, people use voluntarily their personal email accounts. This brings potential challenges when individuals who possess the knowledge are no longer with organisation. For instance, emails that were analysed as part of data collection were retrieved from a personal account by chance; otherwise, it was hard to access them because the owner of the email account is no longer with CMED. To encourage the use of email system, the authors recommend having institutional email accounts official communication mechanism, which will be there regardless of the presence or absence of a particular user.In addition to emails, CMED is encouraged to explore other technology-based systems that can enhance social interactions and centralised storage of the digital content such as user manuals, tutorials, and even spatial data. This will provide easy access to the information by individuals when a need arises. Krumova and Milanezi [7] point out that information and communication technologies (ICT) are increasingly favouring the diffusion of knowledge with reduced investments. They further argue that social computer applications assist greatly in reducing formal communication barriers and open new possibilities for organisations to boost knowledge creation and sharing. However, the potential challenge is the reliability of information infrastructure in developing countries like Malawi.

6. Conclusions

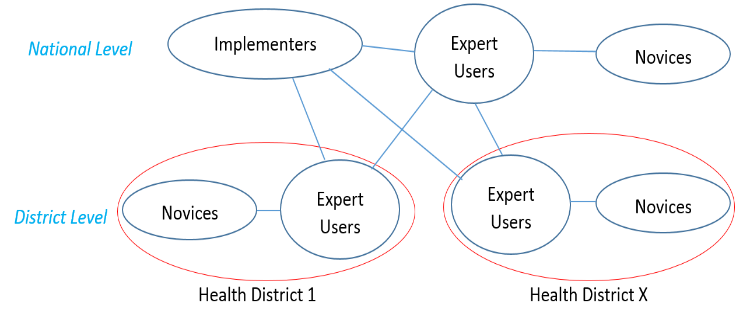

- This case study confirms that interactions between GIS implementers and users facilitate individual knowledge sharing. The paper has discussed how implementers interact with users in GIS implementation for health management and how their interactions can influence individual knowledge sharing. CMED takes user training and work teams as main strategies for sharing knowledge with the supplement of manuals and emails. Table 2 summarises interactions between the implementers and users and opportunities to share knowledge.From the discussions above, the authors have noticed that GIS knowledge and skills are available at the national level through collaboration and there is a need to share them with the expert users at the district level. Collaboration has provided the platform for acquiring GIS knowledge from individuals outside MoH but the challenge is how to continuously accumulate and maintain it. The authors emphasise on the learning-by-doing strategy [13] because, for example, it provides an environment for accumulating tactic knowledge which contributes the large portion of individual knowledge. Apart from the user training, CMED needs to continue promoting work teams with inclusion of HMIS officers in some GIS implementation activities and in so doing the officers can have a chance of building personal relationships and social networks with experienced users for continuous knowledge sharing. Some task-related knowledge (know-what) can be codified as part of documentation so it might easily be shared by a large number of users with the support of technology-based systems. In conclusion, the authors can confidently say that the way the implementers have interacted with users provides opportunities to share knowledge but much is desired particularly the utilization of technologies.

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML