-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Environmental Engineering

p-ISSN: 2166-4633 e-ISSN: 2166-465X

2016; 6(1): 22-31

doi:10.5923/j.ajee.20160601.03

A Total Design Control Management Strategy for Sustainably Designed Products

Anthony Johnson1, Andrew Gibson2

1MSDE Scheme, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, South Korea

2Segelocum Ltd, Ferry House, Littleborough, Retford, United Kingdom

Correspondence to: Anthony Johnson, MSDE Scheme, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, South Korea.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The creation of new products within the Principles of Sustainability requires a particular management approach that transcends the usual pure design approach. The design process, however, provides the framework for the Management of Sustainability, its implementation and its measurement.This paper builds on previous work by Johnson & Mishra who introduce a Sustainable Life Value model which is further developed to create a Total Design Control strategy for managing the implementation of the Principles of Sustainability within the product creation process. The fundamental feature of this strategy is that the design function is the only function within the product creation process that can overview, specify and apply The Principles of Sustainability to the whole life of the product.

Keywords: Sustainability, Environmental audit, Embodied Energy, Total Design Control, Sustainability measurement, Sustainable design

Cite this paper: Anthony Johnson, Andrew Gibson, A Total Design Control Management Strategy for Sustainably Designed Products, American Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 22-31. doi: 10.5923/j.ajee.20160601.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Brundtland Commission report, published in 1987, entitled "Our Common Future" introduced the concept of Sustainable Development, which is "Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs". Thus sustainability was added to the driving forces of political, social and financial equity. The commission defined three “pillars” (3P’s) of sustainable development, namely• Economic growth• Environmental protection• Social equalityThis was developed by Elkington and others into the concept of the triple bottom line, [1] where corporations could benchmark their performance as producers of goods and services in all three areas, by measuring:• profit• interaction with stakeholders • net effect on the environmentAt first sight, it would appear counter-intuitive for a company to focus on their environmental impact, particularly where this could have an apparently detrimental effect on their bottom line or profit, which was the first and still most important of the “3Ps”. However, changes in public attitudes, certainly in the developed world have begun to manifest themselves in the form of legislation and market pressure. Thus governments, adopting a typical stick and carrot approach, have penalised high energy users through high tax takes on fossil fuels, whilst allowing carbon credit trading to benefit the more efficient and effective production processes. Consumers increasingly review energy efficiency ratings for domestic appliances or fuel efficiency for vehicles and make purchasing decisions based on recycled material content or end-of-life destination for product packaging. It therefore behoves any good company to ensure that it is seen to meet or exceed these demands, not the least as a way of capturing a share of the most lucrative market segments.Thus, it seems, a drive to sustainability is inevitable in new product development. But what is sustainability to a manufacturer of engineered products?True sustainability could be summarised as: Development and use of products and services where ZERO resources are taken from the Earth. Logically, it can be argued that true sustainability can never be achieved, and that what we are seeking to do is reduce the negative environmental impact of our consumer society as we move forwards. We propose that this can best be achieved by applying the Principles of Sustainability at the design stage of the product creation process.

2. Total Design Control (TDC)

2.1. Overview

- Total Design Control is a management strategy that considers the whole life of a product so that the Principles of Sustainability can be implemented. These range from material sourcing through to end of life disposal. It is intended that the strategy is applied at the design stage of a product creation process and that the design team should comprise appropriate specialists who can influence the design of the newly created product. Each Life Phase is therefore scrutinised in terms of energy usage so that the principles of sustainability can be applied.

2.2. The Life Phases of a Manufactured Product

- The life analysis of a typical product shows that there are six phases which can be influenced by the design function put forward by [7] Johnson & Mishra.The model shows how the six phases can be linked and coordinated by the design function. The implementation of the model requires thought and consideration for each of the phases during the process of product design. For instance, it is the design function that can specify the sustainable source of the material. It is the design function that can integrate an easily maintainable device by creating easy access and interchangeable, sacrificial components. Furthermore it is the design function that can help determine the method of manufacture, and facilitate simpler end of life disposal if the design incorporates easy separation of variant materials.

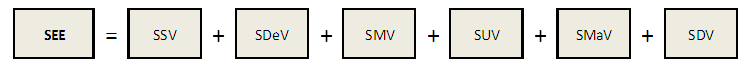

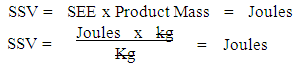

2.3. The Concept of Embodied Energy as a Measurement Device [2]

- The measurement of sustainability is particularly difficult and may take several forms depending on the required outcome of the quantification process. Some evaluations may use carbon footprint, where others such as Ecolabel or Blue Angel use a complex mix of resources consumed and pollution emitted during the whole life cycle. Since the creation of physical products requires energy at every life phase and it is proposed therefore that embedded energy, measured in Joules, is the optimum metric. In order to form a product from original source material, energy is applied during the various manufacturing processes and in transport. This total amount of energy can therefore be termed "Embodied Energy". This allows the designer to apply a sustainable efficiency rating to his work.The design objectives model, [3], [7] shows variables for Embodied Energy at each life phase. These are explained as follows:• SSV: Sustainable Source Value: Embodied Energy required to source the material.• SDeV: Sustainable Design Value: Embodied Energy required in the product design process• SMV: Sustainable Manufacturing Value: Embodied Energy required to manufacture the product• SUV: Sustainable Use Value: Embodied Energy used by the product during its useful life• SMaV: Sustainable Maintenance Value: Embodied Energy required during maintenance processes• SDV: Sustainable Disposal Value: Embodied Energy required to dispose of the product

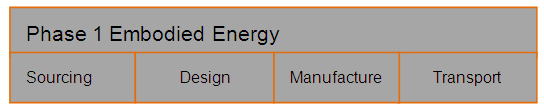

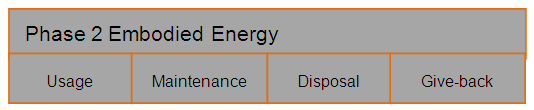

2.4. Phases 1 and 2 of the Whole Life of a Product

- Consider a product when it reaches the end of its life. Energy will have been expended in its sourcing, design, manufacture, usage, through to the energy required to dismantle and dispose of the individual materials. This can be considered as "Embodied Energy" [2]. The measurement of Embodied Energy can be split into two phases:Phase 1 Embodied Energy (shown in figure 1)Phase 2 Embodied Energy (shown in figure 2)

| Figure 1. Phase 1 Embodied Energy |

| Figure 2. Phase 2 Embodied Energy |

3. Total Design Control Management Strategy (TDCMS) (influenced by [5])

- Total Design Control is management approach that combines the classic design process with techniques and measurement devices that can control and reduce the embodied energy within a product. Thus far it has been shown that The Design Function is the only function that can overview and influence the product during its six life phases. It is therefore argued that The Design Function should design-in features that actively reduce Embodied Energy and encourage Energy Gleaning. In order to accomplish this task The Design Function has to combine disciplines normally considered to belong to other phases of the life cycle. The “Design Team” should therefore comprise expertise from: design, management, sourcing, manufacture, maintenance and material recovery to name but a few. Such a core design team would therefore be in “Total Design Control” of the six life phases, coordinating the six phases and applying Sustainability Principles. The quantification of energy at each Life Phase enables analysis of the embodied energy and its eventual reduction to an optimum level. The Total Design Control Management Strategy (TDCMS) can be seen in figure 3. This links management control elements to the Classic Design Process, forming a process association key.

| Figure 3. Total Design Control Management Strategy |

3.1. Sustainability Measurement

- The measurement of sustainability involves the quantification of the Embodied Energy within a product in joules. The measurement process is possibly one of the most important elements of the management strategy since an Energy Audit is taken at various stages as the product progresses through the design process. The aim therefore is to feedback the predicted and measured Embodied Energy so that, if necessary, partial redesign may be applied to the product to reduce further the Embodied Energy.In order to understand how to measure the energy added to and hence embodied in a product it is necessary to follow the mass flow from primary extraction through the various manipulation processes. The transport of the material from one process to the next was also considered in the calculation. Adding energy values applied to the product through all the life phases generates the Specific Embodied Energy (SEE = Joules/kg) as shown in figure 4.

| Figure 4. Specific Embodied Energy (SEE) |

3.2. Classic Design Process

- When a product is designed there is a general process applied by the designer. This starts with the designer receiving the brief (need), which is then processed so that the designer has a complete understanding of the requirements in that brief. This process culminates in the development of the Product Design Specification (PDS).The next stage in the design process is conceptual design, within which several alternative design options may be considered by comparing parameters. This phase culminates in the concept design and is represented by the Concept Design Specification.Once the designer has received acceptance of the concept design, the functioning product is designed in detail by designing the overall product and its components, selecting materials etc. This culminates in a technical specification that would normally include detailed drawings and specific data for purchase and manufacture. Manufacture, assembly where appropriate, and test are then the final phases before the product is shipped to the customer.

3.3. Management Control and Coordination (Influenced by [1])

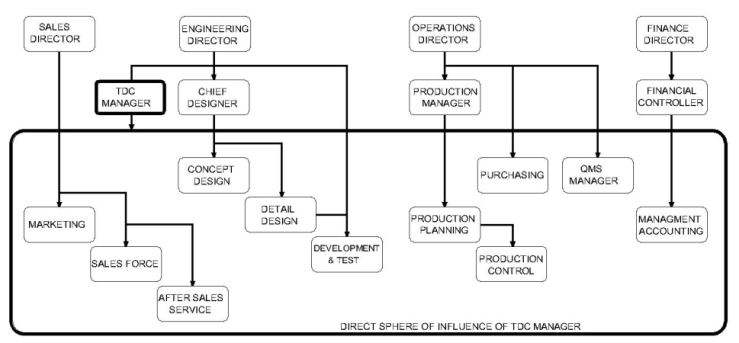

- In the early days of the industrial revolution, successful manufacturing companies were typically led by innovative and entrepreneurial individuals, whose motive and ethic became the motive and ethic of the company. Some successful companies today are still personality-led, but the majority of companies with institutional shareholders tend to be either finance-led or possible marketing led. This leads to a drive towards the financial bottom line, where the design function takes the role of taking cost out of each generation of new products by taking advantage of new materials and methods, whilst being mindful of the customers’ needs and desires as determined by the marketing function.In order to meet the demands of all three components of the 3BL (Triple Bottom Line), and specifically to optimise the sustainability of a company’s products or systems, the Design Function is pivotal. It is the design function that is uniquely placed to determine the in-built or designed sustainability of an engineered product or system, through choices in materials, materials sourcing, manufacturing methods, ease of assemble and maintenance and the like. These choices will help determine the embodied energy of the product or system, which can then be used as a comparative measure to judge the ecological contribution of the product or system.The shoulders of a single designer would indeed be broad to carry such a herculean weight, so a systematic management process is proposed, to be undertaken by a design team, which would normally require input from marketing, procurement, production, quality, maintenance or customer care, and finance. Nonetheless, each design team must have a champion to:• advise on issues of sustainability across the product life cycle• liaise with other specialists, such as manufacturing and procurement to ensure optimum performance of external components and internal manufacturing processes• ensure that improvements in sustainability are seen to benefit the producer of the product or system as well as the customer and the environment• set up and use measurement metrics• audit the process and provide regular feedback on a product-by-product and a global basisThis “champion,” the TDC Manager co-ordinates or manages the TDC Systems. He or she will be responsible for structuring the system, ensuring full participation by stakeholders external to the design team or function, and designing and managing the audit process.As with the dramatic changes in the approach to quality introduced by Taguchi [3], [4], and the need for well-supported QMS management, this kind of cultural shift within a design and manufacturing organisation will only be effective if the TDC manager reports directly to senior management, and that senior management is committed to the implementation of the TDC strategy. The need to drive a new way of thinking will inevitably lead to challenges from those entrenched in past methods. The proposed structure ensures that the TDC manager has a co-ordinating and influencing role across the matrix, whilst being supported by a direct reporting line to senior management, as shown in figure 5.

| Figure 5. Management Structure of a Typical Engineering Company, showing position of TDC manager |

| Figure 6. The Role of the TDC Manager across the Phases |

3.4. Design Brief

- As a new product or system design project is conceived, the TDC manager must set up the systems including organising regular co-ordination meetings and events and aligning the audit timing with the design project management or Gantt chart. Brief Leading to Product Design SpecificationAs the design specification is drawn up for the product, the TDC manager must ensure that the design and marketing teams seek input from materials and production experts, and work with management accounting functions to set up appropriate auditing systems. Concept Design During the concept design phase, the audit tools can be used to provide an iterative feedback loop that helps drive materials selection, make-or-buy, cast or forge and other similar decisions. There is a need for good co-ordinations skills on the part of the TDC manager to ensure that valid inputs are made by all areas of expertise within the company, and possibly to introduce external expertise where required, whilst allowing the design team the space and scope to bring their skills and experience to bear in the design process. Using the combined input information and the outline product design concept, the TDC manager can conduct the primary audit and hence give an indication of the likely sustainability impact of the proposed product, product range or system. Detailed DesignAs the design process moves forwards, the same auditing process is then applied to individual components, whereby relevant tools are applied to ensure optimised Embedded Energy, strength to mass ratios and sourcing and manufacturing efficiency, without losing sight of the original design brief as defined by the design and marketing teams within the Product Design Specification (PDS). Auditing component by component applied at this stage will give a more detailed and realistic Embedded Energy value. Product SpecificationOnce the detailed design and parts lists are complete, the key focus of the co-ordination role moves to materials management, manufacturing and procurement, with feed-back inputs both to and from the design team as issues are highlighted during prototyping or first-batch production. The management accounts team once more becomes involved in quantifying the cost effects of manufacturing and procurement decisions. Manufacture and TestDuring the physical process of manufacturing and testing, and subsequent launch into the market, the TDC manger must continue to liaise with materials management, manufacturing and procurement teams and with sales after-sales and marketing to gain initial indications of performance in service and customer perceptions. As these are typically used to make any minor adjustments and refinements to the beta test products, the TDC manager needs to ensure that the sustainability impact of these amendments and adjustments is noted and recorded. As the manufacture and Test procedures are completed and the product is ready to be shipped to the customer the Final Sustainability Audit (FSA) should be carried out. It is this audit that will provide the data for the “Certificate of Sustainability” which is the value of Embedded Energy within the product. Market FeedbackAs market feedback comes through following the product’s extended use-in-service and eventual end-of-life disposal, the actual, rather than estimated, values for the second phase embodied energy start to feed back. At this point, the figures from the FSA audit can be validated and improved, and the lessons learned can be fed back to the design team, specifically into the materials sourcing, design and manufacture aspects of the product in order to:a) seek further improvements in the design perhaps creating the Mk2 productb) inform the design process for further new products

3.5. Design Implementation and Application Methods

- The application of the Principles of Sustainability requires the design function to develop the components and product in such a way as to reduce the Embodied Energy by applying a number of techniques. Several of these techniques are already in standard use and are aligned with reducing cost, but often the designer is preoccupied with reducing manufacturing costs and may not consider the costs of usage, maintenance or disposal which are the life elements in the Phase 2 Embodied Energy Phase. When each of the life phases is considered in turn, a reduction in embodied energy should be the reward. The examples below indicate where embodied energy can be reduced phase by phase:Sustainable Sourcing• Use recycled materials• Use local materials• Minimise the material to be re-moved• Re-use components• Use certified sustainable materials where possibleSustainable Design Approach• Optimise for particular usage• Reduce time to manufacture and assemble• Include modules where possible • 3D modelling in preference to building prototypes• Design for ease of manufacture• Design-in easy assembly• Design-in easy disassembly for maintenance and material separation at disposal• Minimise the number of parts• Design multi-use parts• Reduce massSustainable Manufacture• Minimise parts• Use multifunctional parts• Reduce machining• Reduce weld length when fabricating• Minimise handling• Aim at assembly from one direction• Work within a smart factory environmentSustainable Usage Application• Introduce fuel efficient engine and transmission systems• Design-in reduced mass, this reduces fuel consumption, material sourcing, etc.• Use natural energy sources, e.g. wind, solar• Operate machinery within design parameters• Use modules for speedy change of usage• Keep well maintained for optimum performanceMaintenance for Sustainability• Increase the life of the product through maintenance• Predict component life for planned maintenance• Design-in easy removal of components• Design-in serviceability in the field rather than a workshop• Design-in lubrication delivery systems• Ensure sacrificial components (bearings, seals, etc.) are easy to replaceDisposal for Sustainability• Reduce the components sent to landfill• Design-in components that can be separated easily into material classes• Reuse components which are not yet at the end of their life• Recycle materials gleaned from end of life products• When materials and components are truly the end of their life they may still retain calorific value. Rather than landfill use these to generate heat/steam/electricityThis list is not exhaustive but it does show that when the whole life of products are considered as six elements, it is possible to see how the design function can influence and coordinate reduced energy input or energy use within each life phase.

3.6. Sustainability Measurement and Audit

- The measurement of sustainability may take several forms. Elements such as carbon or sulphur could be used as the indicator, but this model uses Embedded Energy as the metric, since this is applied during every life phase. The model thus proposed serves well as a guidance tool, but for it to be a truly effective measure of the design in terms of sustainability; the output must include a feed-back into the management strategy, to allow clear performance improvement indicators.It is therefore critical that a clear method is adopted if the designer is to measure the sustainable efficiency of his design. Furthermore it is also important to the success of the audit process that audits are taken at several key stages as shown in figure 3. The Primary AuditThe primary audit can take place only when the concept design has been formulated. The concept design has estimated, tentatively allocated components, strengths of chassis calculated, running costs, etc. and is an excellent point at which to conduct a relatively accurate concept audit which should give an Embodied Energy Value close to that of the final product. This is the point at which a feasible, conceptual design has been placed on the table for evaluation by the client/company.Such an audit will also highlight where more work needs to be done to further reduce Embodied Energy. The Primary Audit is the first estimate of the Embodied Energy required to create the final product. Figure 7 shows the Total Design Control Management Strategy and the position at which the primary audit should take place. The Primary Audit will indicate the value of energy required to complete the product and hence indicate the level of sustainability. This is merely a first estimation measurement but will allow comparisons to be made with other similar products.

| Figure 7. The Position of the Primary Audit within the TDCMS |

| Figure 8. The Position of the Secondary Audit within the TDCMS |

| Figure 9. The Position of the Final Product Audit within the TDCMS |

3.7. Phase 2 Embodied Energy

- The measurement and prediction of embodied energy in phase 1 of the life process can be achieved reasonably accurately since these are measured values. The value of Phase 2 Embodied Energy, however, is more predictive since during this phase the product is in the hands of the consumer and could be used and abused in unpredictable ways. Furthermore, maintenance and end of life disposal is often left in the hands of the consumer, who may be ignorant of, or indifferent to, appropriate best practice. Market FeedbackData feedback from the marketplace is often hard to determine but is an important factor in influencing a products' design and performance when revisiting a design. Feedback of such information to the design team may be ad-hoc and sketchy but careful organisation may glean accurate market information. The manufacturers of high value products such as passenger vehicles are able to apply a complex feedback system through maintenance franchises who naturally feedback repair and maintenance information to the manufacturer. This information is therefore used to improve the product and determine trends for new products.Phase 2 Embodied Energy is notoriously difficult to evaluate accurately and is the focus of further detailed work in predictive Embodied Energy evaluation.

4. Conclusions

- It has been shown that the employment of a Total Design Control Strategy within the design and manufacture process can influence the whole life process of a product. This can be done by dividing the life of the product into six life phases and implementing a minimum energy application strategy to each phase.Implementing the strategy is best achieved by the imposition of good design practice. Clearly, some of the tactics and methods discussed under the best practice concept are already in use on a daily basis in order to reduce costs. There is, however, so much more the designer can accomplish by including some elements across all the life phases normally thought to be out of the designers' control.The TDCMS would be merely guidance if it weren't for the measurement element which feeds back to the Total Design Management Control to trigger the re-evaluation of certain design elements to improve/reduce the Embodied Energy value. In this way the Sustainable Life Value (SLV) metric can be used as an accurate comparator and marketing tool for each product.The Total Design Control Management Strategy can influence the whole life of the product from materials sourcing through to end of life disposal. Design techniques and consideration of life phases during Phase 1 and Phase 2 will inevitably lead to a more sustainable product; however, the current Embodied Energy measurement process can only be applied accurately to measured values during the phase 1 period. Due to the vagaries of usage in Phase 2, Embodied Energy is largely predictive and may, at this stage, only estimate the ideal Available Sustainability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Prof Rakesh Mishra, Head of Alternative Energy Research Group, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML