Isaac A. Alukwe

Energy and Environmental Engineering, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kenya

Correspondence to: Isaac A. Alukwe, Energy and Environmental Engineering, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Kenya envisages attaining the middle-level economic status by the year 2030. As the country’s major commercial hub, Nairobi has a rapidly growing population from both in-migration and economic growth. The expanding population is continually increasing the city’s size and creates water supply and pollution challenges, thus, the need to evaluate the order of magnitude of the pollution problem, identify new management strategies and prioritize the development measures to mitigate the likely environmental impacts from the expected new economic status by 2030. Total nitrogen and phosphorus loadings to receiving waters were used as indicators of water contamination. Different development scenarios were modelled to identify water and nutrient related problems and to propose recommendations and mitigation approaches. Results showed that there is scarcity of drinking water (approx. 60 l/cap/day, and in some areas far less) which is pumped 50 km away from the Aberd are Ranges. Additionally, only about 40 percent of the population is connected to the city’s sewerage system. To maintain the per capita water demand at the present level, water supply needs to be increased from the current 172MCM/yr to 410MCM/yr by 2030. The water-nutrient balance showed that the concentrations of total nitrogen and phosphorus in surface water, soils and aquifers are likely to increase by 13 mg/L N and 7 mg/L P, respectively. Most of these nutrient loadings come from inadequate sanitation. The nutrient loadings can be reduced by investing more in simplified sewerage systems in the high density areas, implement latrines in the medium-density areas and communal facilities in densely populated areas. Additionally, encourage use of flush systems and septic tanks in the high-cost and low density areas would be ideal. Construction of public facilities should be encouraged in markets, schools and light industrial areas locally known as “jua-kali sector”. Besides improving sanitation systems, nutrient inputs should be reduced by strategies such as improving treatment plant efficiencies, waste collection rate and by banning phosphorus-rich detergents. Nairobi requires high investments in the water sector to guarantee safe drinking water for all by increasing water supply at the current rate of population growth and to reduce water pollution by developing water saving and nutrient-retaining toilet technologies.

Keywords:

Development scenario, Nitrogen, Phosphorous and Water flow

Cite this paper: Isaac A. Alukwe, Evaluating Implications of Vision 2030 on Nutrient Fluxes in Nairobi, Kenya, American Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 90-105. doi: 10.5923/j.ajee.20150504.02.

1. Introduction

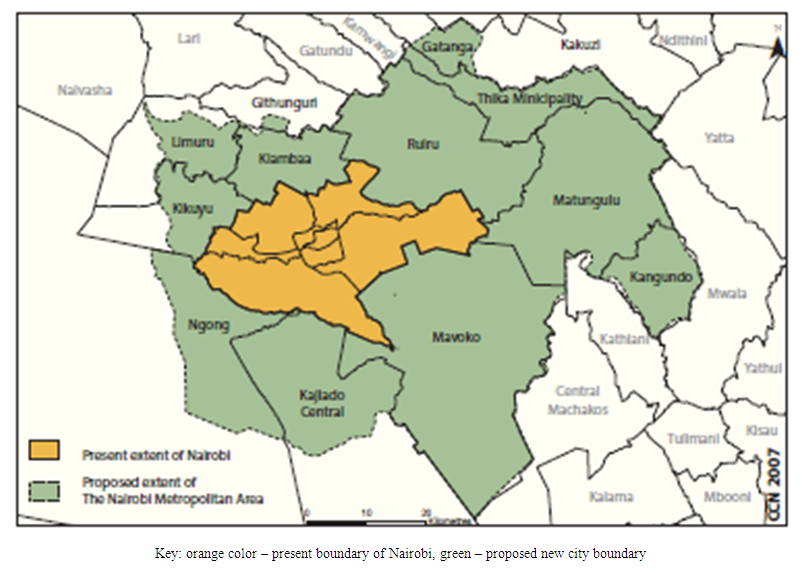

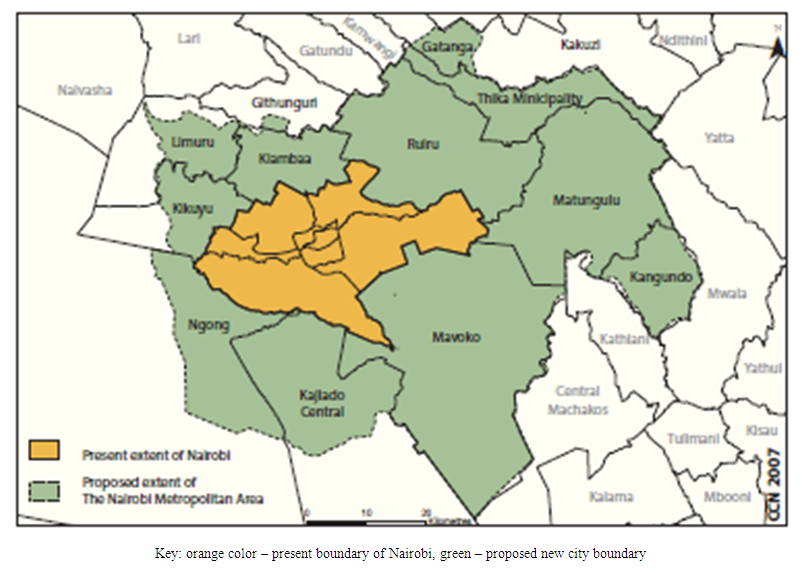

According to [1], Nairobi’s large and growing population is one of the main forces driving the city’s overwhelming environmental challenges. Despite the constitutionally mandated devolution of resources to the grassroots through the County Governments [2], there is still a high rate of rural to urban migration, high birth rates, and poor or inappropriate city planning. These factors combined continue to degrade the city’s water and air quality. As a result, environmental degradation has impacts on human health, social fabric and the economy. The 2007 City of Nairobi Environment Outlook provided a baseline to assess progress in addressing the city’s environmental problems and provided stimulus to the local government to mainstream environmental issues in all development and city planning activities [3]. The Nairobi Metropolitan Development Plan produced in 2008 by the Government of Kenya lays new boundaries of the city (Nairobi Metropolitan Area) (Fig.1). The plan is intended to expand the city to include adjoining towns and municipalities as part of the “Vision 2030” strategy. The plan envisages massive growth in road and rail infrastructure, changes in the informal settlements, and investments in public utilities and services. The ultimate goal isworld-class infrastructure for transforming Nairobi into a global competitive city for investment and tourism. This ambitious agenda calls for a careful planning and execution of projects to minimize impacts on the environment. Tofacilittate and provide tools for the planning process, it is therefore important to evaluate the order of magnitude of the pollution problem, identify new strategies and prioritize the improvement measures to mitigate the likely effects that may arise from the expected economic status by 2030. Thus, this paper aims to analyze development scenarios and the implications of this growth. | Figure 1. Present and proposed city boundaries |

2. Study Site

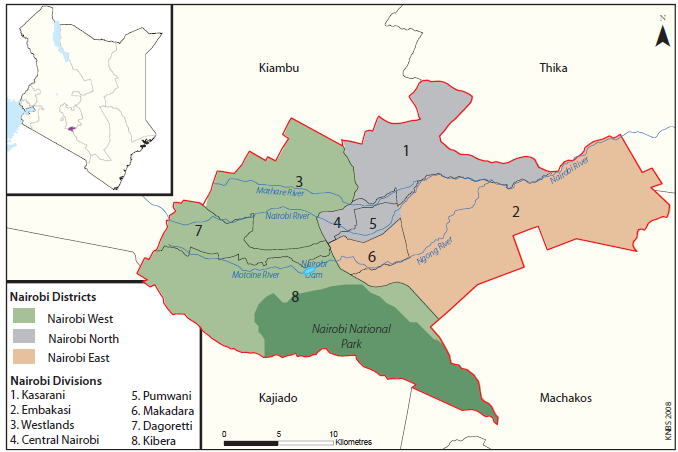

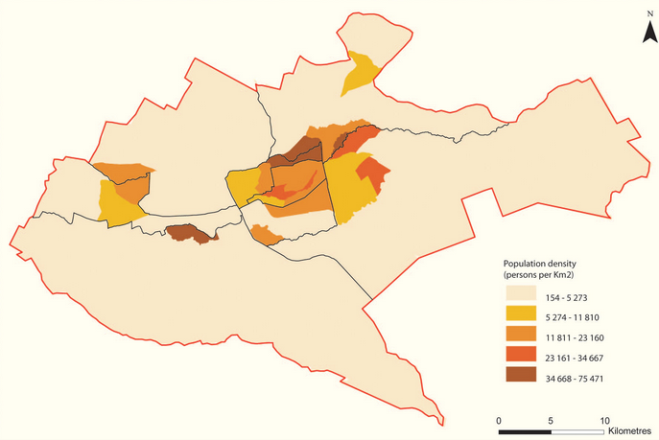

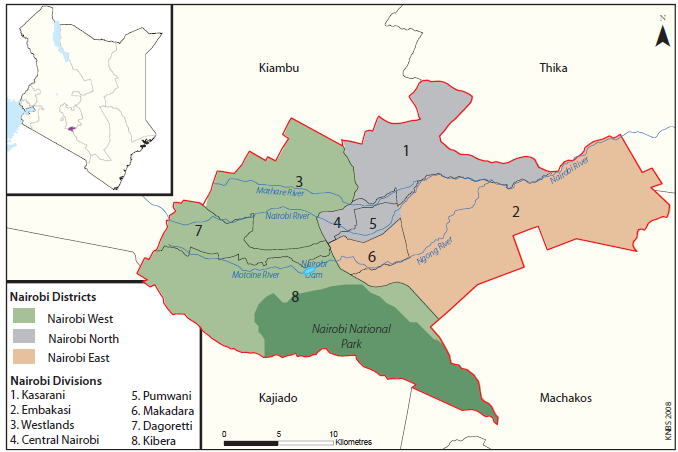

The City of Nairobi (Fig.2) has an area of about 700 km2 and lies at 1,600 to 1,850 m above sea level [4]. According to the 2009 Population Census [5], the population of Nairobi is estimated to be around 3.1 million people. [1, 6] reported that Nairobi enjoys a temperate tropical climate with two rainy seasons. Highest rainfall is received in March and April and the short rainy season is in November and December. | Figure 2. Study area - Nairobi Watershed and City Boundary |

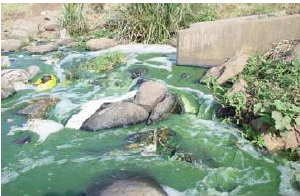

Nairobi’s emergent population has outstripped the city’s ability to deliver adequate services such as education, health care, safe water, sanitation, and waste collection [1]. The major environmental problems faced by the city include rapid urbanization, air and water contamination, burgeoning of informal settlements, and inadequate water supply, wastewater collection, and solid-waste management. The rapid growth has increased the demand for land and led to land speculation, forcing the poor to settle in fragile and unsavory areas where they face hardships due to a lack of proper housing and public services and where they are vulnerable to environmental hazards. A total of 134 informal settlements were reported by 1995 [1, 3, 6].The city’s drainage basin consists of three major tributaries (Nairobi, Ngong, and Mathare) whose subbasins are found within the Kikuyu and Limuru Hills. Ndakaini, Ruiru, and Susumua dams are the principal sources of water for Nairobi. These dams are all on rivers emanating from the Aberdare Forest which is more than 50 km away from the city. Wastewater handling, collection and treatment in the city has not kept up with increasing demands from the growing population and is inadequate to treat the amount of industrial and municipal effluent entering the Nairobi River and its tributaries.The Nairobi River also receives inadequately treated effluents from the Dandora Sewage Treatment Works (DESTW) (Fig. 3), sewer overflows and stormwater runoff from the city’s Central Business District (CBD) and its environs.  | Figure 3. Nutrient rich effluent from the Nairbi wastewater treatment plant |

Much of the household refuse from informal settlements that have no public waste collection services also finds its way into the river as does sewage and runoff from pit latrines and other on-site sewerage-disposal methods. Sanitation facilities are very basic and poorly maintained in many informal settlements, consisting of open drains, communal water points, and pit latrines, and no systematic solid waste disposal. Besides the locally generated water pollution, Nairobi receives effluents entering the tributaries from human activities further upstream. Poorly treated sewage and uncollected garbage have contributed to a vicious cycle of water pollution, water-borne diseases, poverty, and environmental degradation. Water pollution carries environmental and health risks to communities within Nairobi, especially the poor who may use untreated water in their homes and to irrigate their gardens [1]. Peasants practicing farming along the river and its tributaries usually use polluted waters and raw sewage for irrigation, exposing both farm workers and consumers to potential health hazards like diarrhea and helminthic infections. Almost half of the vegetables consumed in the city of Nairobi are grown on the banks of polluted rivers [1]. This paper evaluates different development scenarios to elucidate the order of magnitude of water pollution problems, identify new mitigation strategies and prioritize the improvement measures. Scenario analysis is a process of evaluating possible future events by considering possible alternative outcomes. The procedure tries to consider possible developments and turning points, and the consequent scope of possible future outcomes are observed for future planning and decision-making.

3. Methodology

3.1. System Analysis

The system boundaries are delineated by Nairobi's inhabited area as at 2009. The water flows in the urbanized area are considered in this study in order to identify major flows and to be able to prioritize the challenges of nutrient fluxes. Total nitrogen (N) and total phosphorus (P) transported by water in the urbanized system area are modelled. Water and nutrient flows are given in million cubic meters peryear [MCM/yr] and tons per year [t/yr], respectively. Water demand data for the year 2008 were used where available. Where necessary, older data were adjusted using bestprofessional judgement. Average rainfall time series data for the last 30 years were used. Annual evapotranspiration (ET) was estimated using 2007 and 2008 climatedata (Kenya Meteorological Department, personal communication).

3.2. Mass Flow

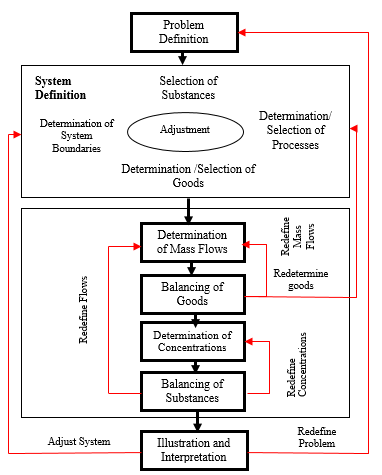

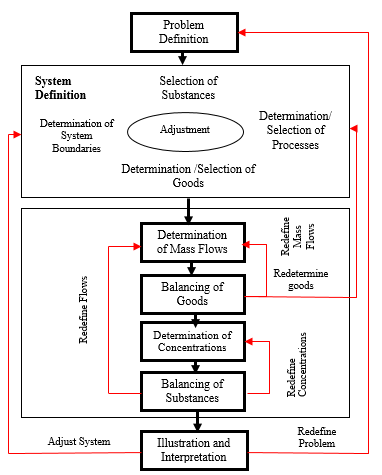

A mathematically conceptualized material flow analysis (MFA) model was used in the study. The MFA describes, quantifies and models the material flows of the system considered [7, 8]. The method consists of four main steps but with some sub-steps included: (1) system analysis, (2) model approach, (3) data acquisition and calibration and (4) simulations [8]. The method of MFA describes the fluxes of resources used and transformed as they flow through a region, through a single process or via a combination of processes. It analyzes the flux of different materials through a defined space and within a certain time. In industrialized countries, MFA has proved to be a suitable instrument for early recognition of environmental problems and development of solutions to these problems [9]. The significance of the method lies in the overview that can be obtained on the entire system [9]. The scientific basis is the law of conservation of matter and energy [10]. The MFA procedure is iterative and requires stepwise checking and continuous adaptation. The whole MFA procedure is summarized in Fig. 4. | Figure 4. MFA Procedure |

The terminolgy used in this study and is defined as follows [7, 9]:Substance: Any compound (chemical) composed of uniform units. All substances are characterized by a unique and identical constitution and are thus homogeneous. Examples: N and P.Goods: Substances or mixtures of several substances valued by men. Examples: drinking water, air, food, solid waste, wastewater and sludge.Process: The transformation, transport, or storage of goods. Examples: (1) private households converting goods (inputs) to excreta, solid waste, emissions, etc. (2) Wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) converting sewage to treated wastewater, sewage sludge and gases. (3) Agriculture converting N, P and CO2 and water to crops. An example of a storage process is a landfill where solid wastes are stored.

3.3. Water Balance

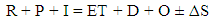

A water balance of the system was derived by water inflows and outflows from the system boundary. For an urban system the following equation applies: | (1) |

Where R=Rainfall, P = Pipe water supply, I = other system inflows, ET = Evapotranspiration,D = Drainage of storm water, O = other system outflows, and ΔS = Storage change of soil and aquifer.Equation (1) provided the basis for the MFA model development and was applied in the computation of subsequent flows.

3.4. Substance (Pollutant) Flows

Two indicator substances: N and P which are key nutrients/pollutants found in wastewater were chosen for simulation in order to derive annual pollutant loads [tons/year] into the environment, groundwater and surface waters. Large inputs of nutrients especially N and P arising from human activities can lead to eutrophication, adversely affecting the ecology and limiting the use of rivers for drinking water and recreation [11]. The N and Pcan also be correlated with other pollutants in wastes, e.g. pathogensand elevated nitrate levels (10 mg-N/L) in drinking water are a risk to human health particularly infants less than 6 months old. Nitrogen and P are also easier to model (especially P).Flows provided in the defined system matrix were three as follows: input flows, Ij, internal flows Fi,j and output flows Oi; where: i and j denoted balance volumes at origin and destination, respectively.

3.5. Model Selection and Development

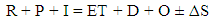

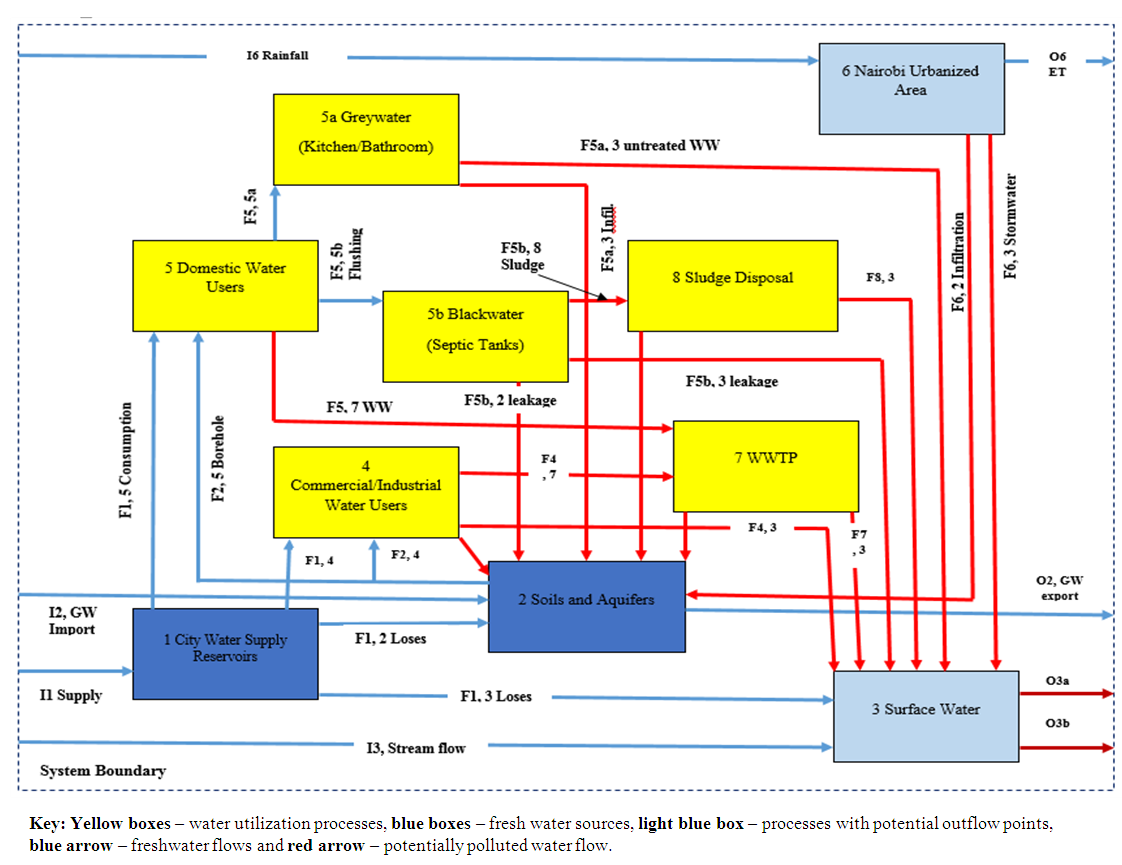

The method of MFA was used for the analysis and description of the material balances in the study system [9]. At the beginning of a MFA, the following questions were addressed for the system analysis: Which goods and processes are considered? What are the system boundaries? What time period should be modelled? A material flow matrix based on N and P elements was developed in order to get insight into anthropogenic water pollution by nutrients for a period of one year. Even though this time step fails to capture seasonal changes, it is important since storage change for most goods is basically assumed zero.The modeled system was conceptualized as a process of flows containing boxes and arrows (Fig.5). Boxes either represent water bodies, water users or a compartment involving water pollution or treatment. Arrows represent the water and pollutant flows between two boxes. Water flows were expressed in MCM/yr, N and P in metric tons per year (ton/yr or simply as t/yr), respectively. In this context, processes were denoted either as system Ij, Fi,j or Oj and were shown as arrows in the schematic showing the system analysis (Fig. 5). The elements called “goods” by [9], were visualized as boxes and represent an imaginary unit where materials were stored, consumed or produced. Fig. 5 shows the Mass Flow Scheme for the urbanized area of Nairobi. | Figure 5. Nairobi mass flow scheme and system boundarie |

3.6. Definition of Processes

Processes in the system (Fig. 5) as considered were represented by boxes, also referred to as balance volumes. These are system segments in which flows were computed and are basically pathways for water and pollutants/ substances. They included the following: Drinking water from pipe supply- formed by the four main reservoirs supplying Nairobi with drinking water as shown in box 1 (Fig.5), namely; Ndakaini dam, Ngethu, Sasumua and Kikuyu Springs. All the drinking water supply is pumped to the Kabete treatment works from where it is distributed to the rest of the city. The supply volume used in the study was therefore the sum of the discharge of the four reservoirs into the treatment works at Kabete.Soil and Aquifers (box 2) receive, infiltrate and constitute the groundwater source. The soil adsorbs pollutants/nutrients on its particle surfaces, while water infiltrates to the aquifers and therefore acts as a sink for pollutants/nutrients.Surface water (box 3) is basically the Nairobi River basin constituting Ngong, Mathare and other small tributaries. These are subjected to extreme levels of pollution from agricultural fertilizers (not considered in this study), treated sewage, raw sewage and industrial wastes. Significant solid and liquid waste are discharged directly into the river system with no pre-treatment, thereby severely damaging the river ecology as well as posing serious risks to human health. The rivers themselves are now considered an environmental health hazard due to the high concentrations of chemical and bacteriological pollution [1]. However, despite this, nearly half of the urban population one way or another, dependent on them as a source of water for urban agriculture, domestic use and in the worst cases, for drinking. Due to relatively short retention time assumed to be one day, de-nitrification is negligible (which is a fairly quick process especially under these conditions). The flow of groundwater between processes may be difficult to ascertain and thus requires a detailed hydro-geological assessment. Hence, the mass stock change found in this study is only an indicative value which needs to be used with caution.Domestic water users (box 5) refers to water use at household level. It constitutes sullage mainly for sanitation and other households’ purposes such as cleaning, cooking, washing, bathing, watering, etc. Approximately 60% of the total wastewater generated from households world over is greywater (box 5a) [12]. The other component is blackwater (box 5b) which refers to wastewater resulting from use of water closets (WC) and other forms of toilets that forms the main source of pollutants generated from households. Its main inputs are faeces and urine while the outputs include constituents of N and other pollutants such as P. Pollutant sources from both grey and blackwater include organic wastes, detergents, and soap among other compounds.In 1995 the per capita water demand for sub-Sahara Africa, with households connected to the water supply system was estimated to be 18.8 m3 per year for rural and 29.2 m3 per year for urban households translating into 51.5 liters/capita. day (l/ca.d) and 80 l/ca. d respectively [13]. For Nairobi, per capita water consumption was estimated at 60-80 l/ca.d depending on the social classes of individuals [6]. In this paper, the lower value of 60 l/ca.d was chosen since Nairobi faces inherent and unreliable water supply. This value is likely lower in the informal settlements. Water supply failure and rationing is a norm to residents. Estimated Nairobiwater consumption in 2007 was 476,603m³/day [14].Non-domestic water users (box 4) include industry, institutions, commercial sector and agriculture. (agriculture was not considered in this study because of lack of data).The Nairobi urbanized area (box 6) generates surface run-off (stormwater) and groundwater recharge from precipitation. Pollutants emanate from atmospheric deposition, washed out pollutants of organic nature (resulting from open defecation such as “the Kibera slum flying toilets” – feacal matter is deposited in plastic bags and thrown into alleys and streets), run-off from small-scale agriculture and the illegal solid waste dumping. The urbanized area also contributes extraneous water into sewer flows during wet weather of 10% to 100% of total sanitary flows (Qs), (Krebs, 2007, personal communication).Faecal sludge disposal (box 8) constitutes sludge from on-site treatment systems and dry sanitary systems. In Nairobi, sludge disposal involves burying underground or emptying into the main sewer line. Other sources of sludge include the dry sanitation systems such as pit latrines, pour flush among other technologies used for faecal sludge handling. The Nairobi WWTP (box 7) is situated at Ruai; 33 km from the city centre and receives wastewater from the entire urbanized area with 40% of population connected to the sewer line. However, a substantial portion of the collected sewage is lost through sewer overflows and infiltration to soils and aquifers from leaky pipes. Hence, the final yearly amount of treated wastewater is far less than what can be expected from the connected population. Total pollutants removed by the treatment plant were given in the storage change of the balance volumes.

3.7. Scenarios

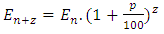

Three scenarios were developed and modelled as follows:1. Implications of population growth on the national development strategy plan dubbed “Vision 2030”2. Implications of implementing different sanitation technologies e.g. WCs versus dry sanitation e.g. EcoSan, VIP Toilets, Pour- flush toilets, and traditional pit-latrines3. Effect of Improved wastewater treatment and solid waste handling.Prediction of the population growth was calculated using: | (2) |

En = number of inhabitants in the base year consideredz = planning period in yearsp = current population growth rate at 4%.The 2009 Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) census value of 3,138,369 [5] was used as a base value.

3.8. Modeling Approach

A mathematical model was developed and implemented in Microsoft Excel for the simulation of material flows. Equations were developed to model for simulations of water, N and P flows. These equations are discussed in section 3.12.

3.9. Data Acquisition and Calibration

For the anthropogenic system boundary considered in this study, a one year investigation data provided adequate steady state simulation [9, 15]. The primary data was acquired through personal interviews and from the Nairobi Water Service Company (NWSC). Secondary data was requisitioned through existing literature research on Nairobi and elsewhere. The NWSC [14] provided data on water demand, distribution, sewer network and the wastewater treatment. The modelling data was compiled that defined the important parameters and coefficients important in the running of the simulation and where no data was available reasonable assumptions and estimations were made. This was due to the fact that MFA can be assessed based on assumptions and cross-comparisons between similar systems and the law of mass conservation of matter applied on each process [7, 9, 15].

3.9.1. Water Demand and Flows Data

The actual water demand in Nairobi is 640,00 m3/day, however for last several years the production capacity of the NWSC has remained at about 481,000 m3/day [14, 16]. Of the 481,000 m3/day nearly 40 percent is lost due to illegal connections and leakages [16].

3.10. Derivation of Key Parameters and Coefficients

3.10.1. Run-off

The water balance was computed using equation (1) provided in section 3.3. The typical values of runoff coefficient were obtained from [17] and used to estimate the run-off / stormwater. The run-off coefficient for the improved / developed area of Nairobi (which includes all the paved surfaces and roads) was estimated at 0.5 and for unimproved 0.2 constituting the unpaved residential areas and informal settlements and vegetated areas 0.2. Since there were no data for the impervious surface, stormwater generating surface was estimated at 0.5. The value took into consideration the fact that in developing countries cities like Nairobi, streets are not well paved and are generally characterised by bare ground beyond the road shoulders and sometimes around buildings. These values were used in modeling system internal flows.

3.10.2. Groundwater Percolation

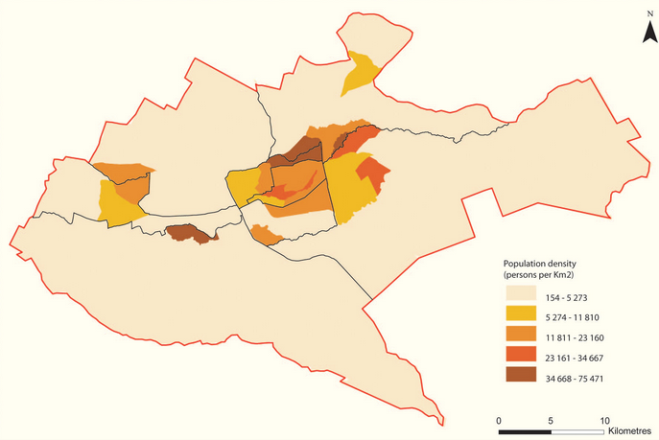

The upstream groundwater re-charge mainly due to rainfall and abstraction was estimated at 25 and 31 MCM/yr, respectively [18]. This translates to a daily abstraction rate of 84,932m³/day which was applied to model simulations. However, the soil infiltration is highly variable depending on soil type, so this value should be used with caution and a more certain figure needs further detailed investigation. | Figure 6. Population density in Nairobi |

3.10.3. Evapotranspiration

Nairobi has tall buildings which interfere with normal Evapotranspiration (ET) and wind movement processes. Tall buildings act as windbreaks which can significantly reduce the ET. The Real Evapotranspiration (ETR) would refer to the sum between the quantity of water evaporated from soils and the quantity of water transpired from the vegetation. From the foregoing definition, it is rather difficultto ascertain the ETR for a large basin like Nairobi. It receives an annual rainfall range of 1200 – 1600mm (the upper watershed areas receive rain up to 2400mm [1, 6]. The actual ET depends on the location in the basin. Traversing across the city shows high variability of climatic zones eastwards, with the western side being wetter than the eastern. Kabete and Dagoretti data for the period 2007 to 2010were used to estimate the ETR.

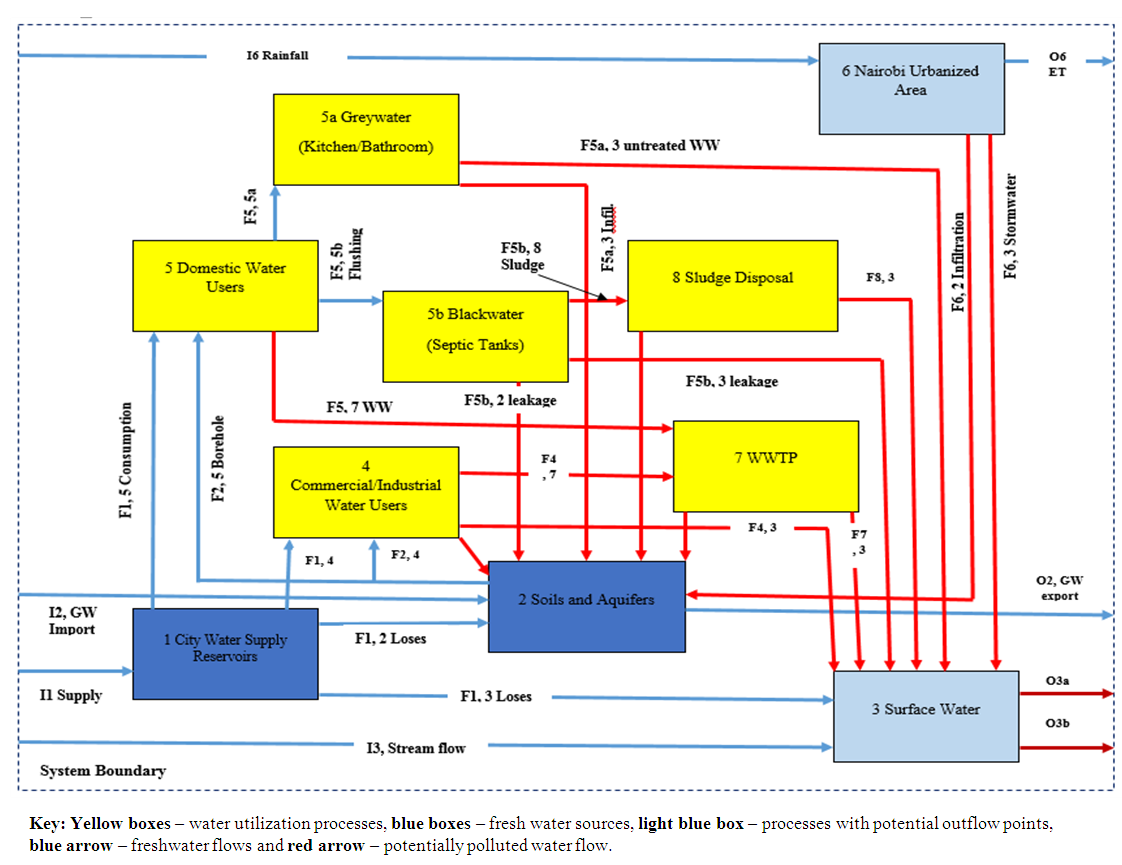

3.11. Mass Loadings from Households

Data on the population distribution across the city suburbs were obtained from [3, 19-21]. The data were useful in estimating the substances flows across the city. Fig. 6 shows population density in the city.

3.12. Model Parameters and Equations

3.12.1. Transfers Coefficients

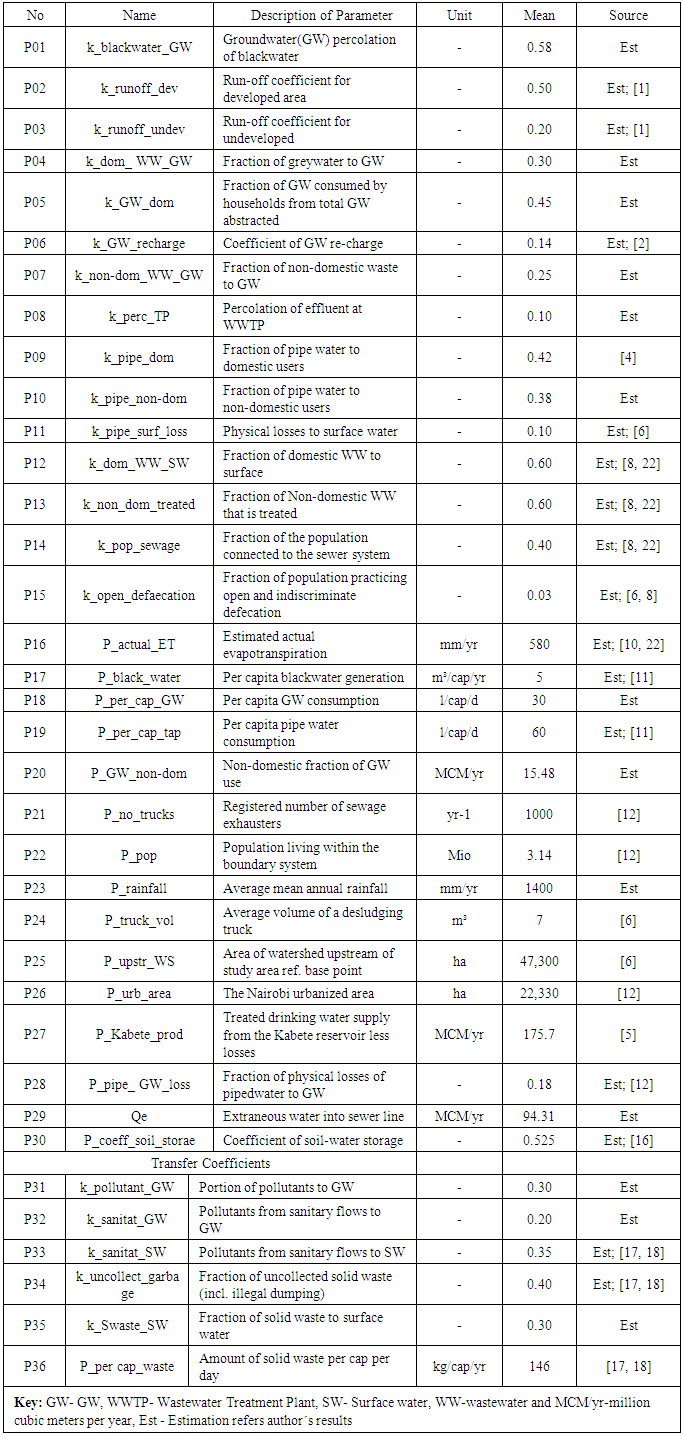

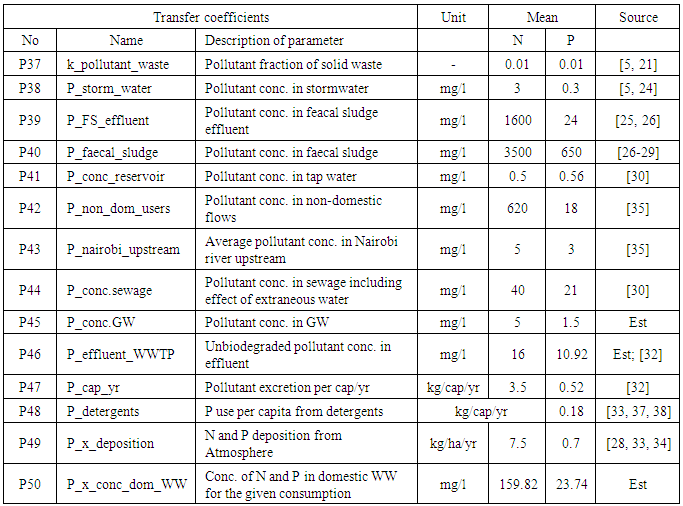

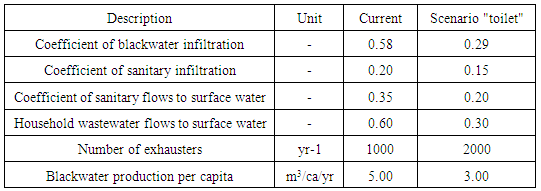

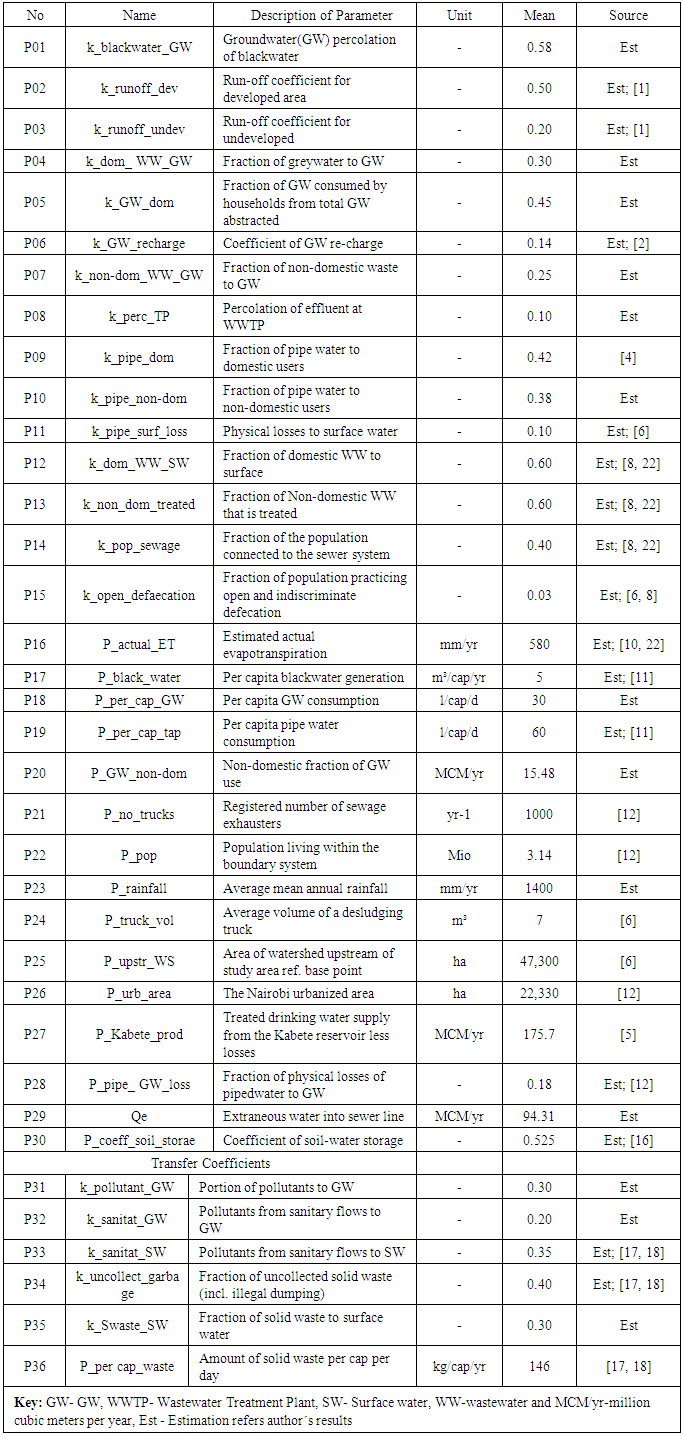

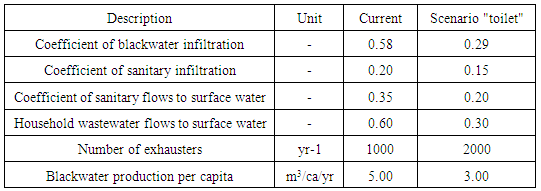

Transfer coefficients describe important ratios and constants required in the computation of the material flows and storages within the model system. These provided the apportioning of the substances in the different processes that gave the percentage of the total throughput of the considered substance transferred into specific output goods. Most of the fundamental parameters and coefficients necessary for this simulation were described and are given in Table 1 and 2. Where data were lacking, reasonable assumptions were made or data were adapted from similar research in other fast growing mega cities elsewhere like Accra Ghana. Table 1. Model Parameter values and description for pollutant flows

|

| |

|

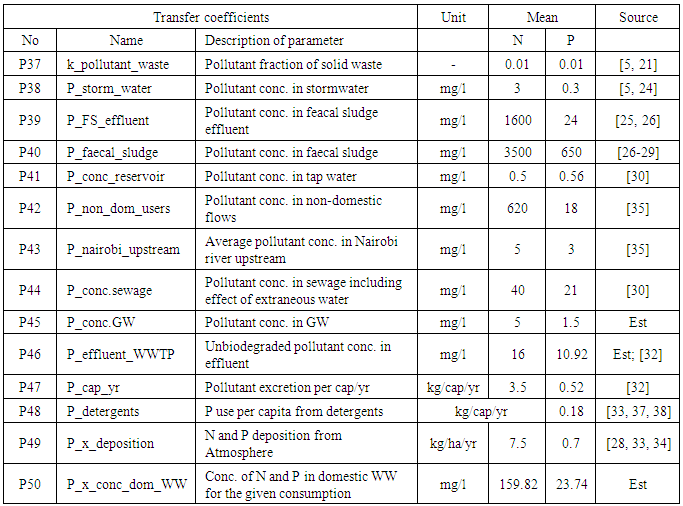

Table 2. Transfer coefficients for specific substances

|

| |

|

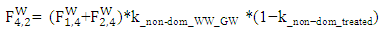

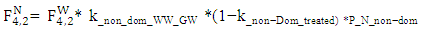

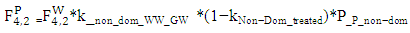

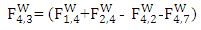

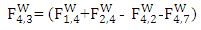

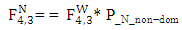

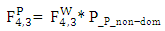

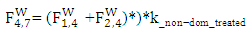

3.12.2. Derivation of Flow Equations

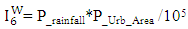

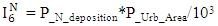

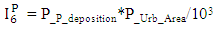

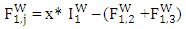

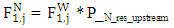

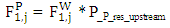

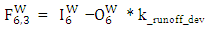

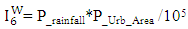

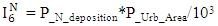

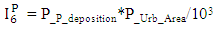

The different mass flows considered were denoted as Parameter  , for j = W, N and P.Where: W = water for all balance volumes n, N = total nitrogen, P = total phosphorous. All mass flows were developed based on the schematic in Fig. 5.The different inflows into the system boundary relate to inputs of the considered parameters (Table 1 and 2). Where necessary, units were converted using conversion factors to form the stated units in the results. The inflow into the urbanized (developed) area was mainly as a result of rainfall and atmospheric deposition of N and P as follows:

, for j = W, N and P.Where: W = water for all balance volumes n, N = total nitrogen, P = total phosphorous. All mass flows were developed based on the schematic in Fig. 5.The different inflows into the system boundary relate to inputs of the considered parameters (Table 1 and 2). Where necessary, units were converted using conversion factors to form the stated units in the results. The inflow into the urbanized (developed) area was mainly as a result of rainfall and atmospheric deposition of N and P as follows:  | (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

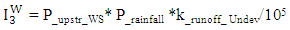

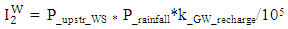

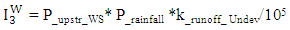

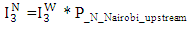

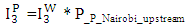

Runofffrom upstream of the system boundary was derived by use of a runoff coefficient for undeveloped area. | (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

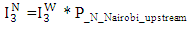

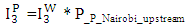

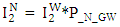

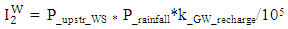

The upstream groundwater recharge for Nairobi was estimated as 25 MCM/yr, with transmissivity of 5 – 50 m²/day [18]. It can then be assumed that the average groundwater flow cannot be higher than groundwater recharge in the upstream area. This is true for a long-term groundwater recharge with a change in storage equal to zero within one year flow regime: | (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

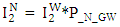

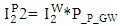

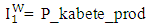

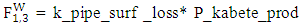

Water supply to the main treatment works at Kabete was simply given by its production to the distribution system:  | (12) |

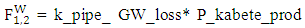

Whereas the NWSC conducts surveillance on leakages within the distribution system and carries-out repairs, a substantial amount of water is lost through undetected leakages for a pipe network buried underground, illegal connections by car wash and vendors. Physical losses and illegal connections within the distribution system describe losses to soils and aquifers (F1, 2) and surface water (F1, 3) computed as follows: | (13) |

| (14) |

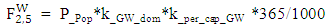

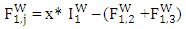

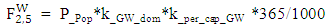

Losses due to transmission were assumed to occur outside the boundary system since the abstraction points are about 50 km away, while treatment works losses are negligible. The water demand data provided by [14] were used during the estimation of piped water supply to non-domestic (F1,4) and domestic (F1,5) water users, respectively as follows: | (15) |

| (16) |

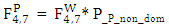

| (17) |

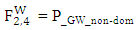

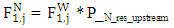

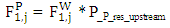

Where j = mass flows to box 4, 5 (Fig. 5) and x = k_pipe_non_dom (box 4) and k_pipe__dom (box 5), respectively (Table 1 and 2).Groundwater abstraction in Nairobi in 2002 was estimated at 31MCM/yr [18]. Certain sectors within the non-domestic users such as schools, industries abstract their own water from the groundwater sources and thus it was imperative that groundwater use is accounted for: | (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

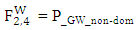

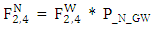

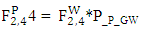

For domestic water users groundwater is commonly used especially by households not connected to pipe supply and some neighborhoods use borehole water for back-up in the event of municipal water supply failure:  | (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

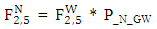

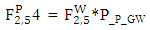

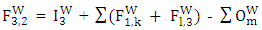

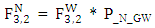

The infiltration and ex-filtration of surface water into the ground and vice versa depends on the seasonal variation between wet days and dry days of the year. Ex-filtration is predominant when flow F3,2 is negative and thus the following equation was applied to flows between the ground and surface waters. | (24) |

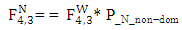

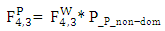

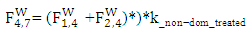

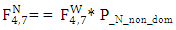

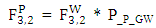

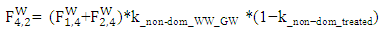

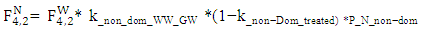

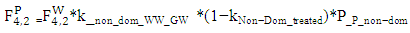

where k = 2,3; l = 4, 5a,b, 6,7,and 8; and m = 3a,b. | (25) |

| (26) |

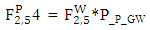

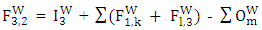

The following equations explain the mass flows associated with the internal flows and discharges into the soil and aquifers and surface water: | (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

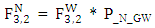

| (30) |

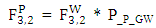

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

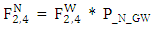

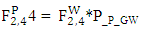

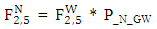

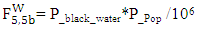

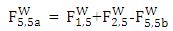

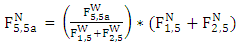

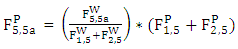

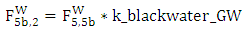

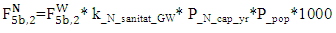

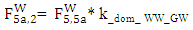

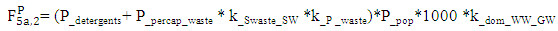

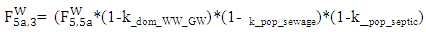

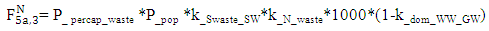

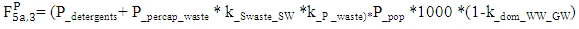

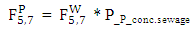

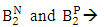

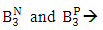

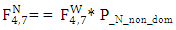

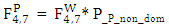

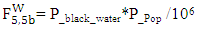

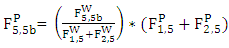

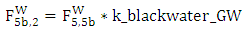

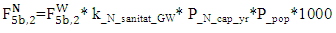

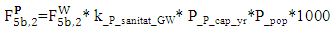

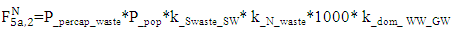

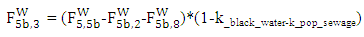

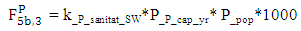

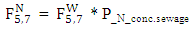

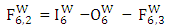

Box 5 (domestic water) provides the sub-boxes box 5b (black water) and box 5a (greywater generated from the remaining domestic supply). Quantity of blackwater produced by households connected to a sewage system is allocated to the box 5b. The corresponding substance flow equations are: | (36) |

| (37) |

| (38) |

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

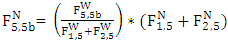

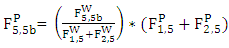

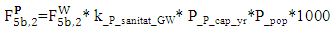

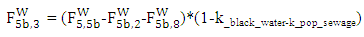

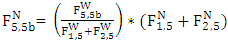

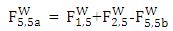

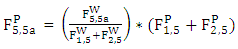

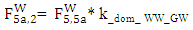

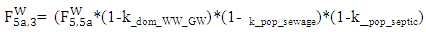

Flows and substances from the domestic box (5a) were then derived and apportioned into different destinations- surface water, GW or WWTP: | (42) |

| (43) |

| (44) |

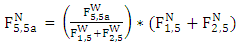

Flows and substance into GW from greywater are derived as follows: | (45) |

| (46) |

| (47) |

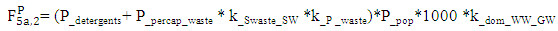

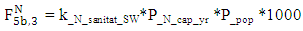

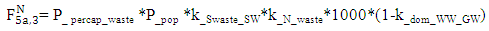

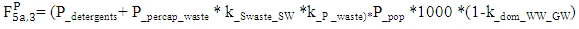

Flows and substances into Surface water result from: | (48) |

| (49) |

| (50) |

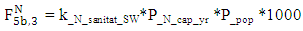

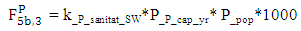

| (51) |

| (52) |

| (53) |

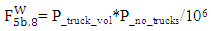

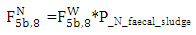

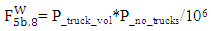

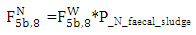

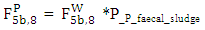

Material flows due to sludge disposal from on-site sanitation facilities: | (54) |

| (55) |

| (56) |

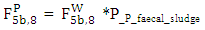

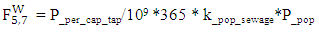

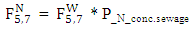

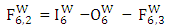

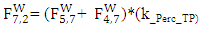

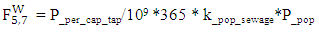

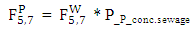

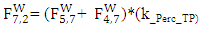

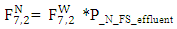

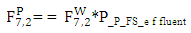

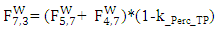

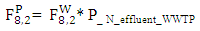

Material flows to the WWTP: | (57) |

| (58) |

| (59) |

Phosphorus deposition by rainfall onto the soil surface was assumed near equal to the accumulation of the same from storm water, hence: | (60) |

| (61) |

| (62) |

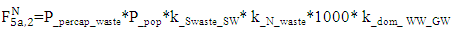

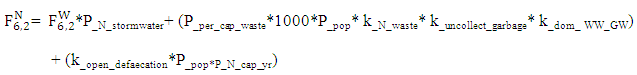

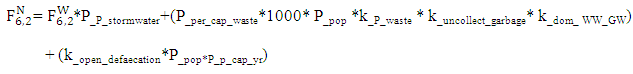

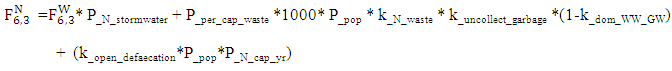

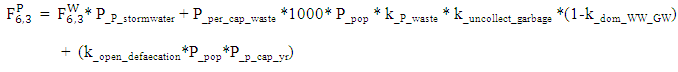

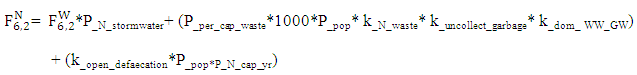

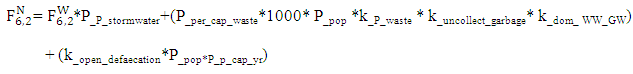

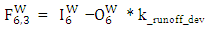

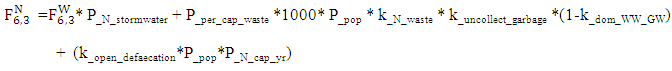

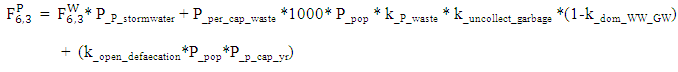

Some uncollected domestic waste finds its way into open drains and surface waters. These include open defecation, uncollected garbage, market waste and industrial waste etc. are washed to surface waters during rainfall. Runoff therefore washes significant N and P loads to surface water: | (63) |

| (64) |

| (65) |

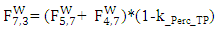

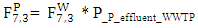

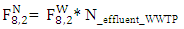

At the wastewater treatment plant there is percolation to the groundwater: | (66) |

| (67) |

| (68) |

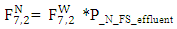

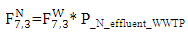

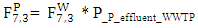

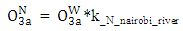

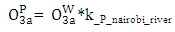

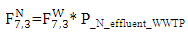

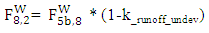

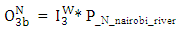

Effluent discharge into the Nairobi River is given by the following: | (69) |

| (70) |

| (71) |

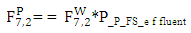

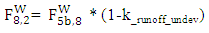

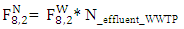

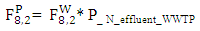

Percolation from buried sludge into groundwater ultimately occurs. Nairobi has no sludge treatment plant but the sludge collected from pit latrines, septic tanks and the wastewater treatment plant is usually buried into the ground or in some cases released into the sewer lines. The impact of this is that there will be percolation and discharge into groundwater and the surface waters. Percolation can be assumed to occur at a rate equal to infiltration of undeveloped land as all the water within the buried sludge finally gets its way into groundwater. Hence the corresponding flows were estimated as follows: | (72) |

| (73) |

| (74) |

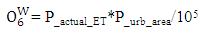

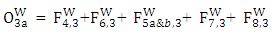

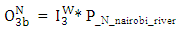

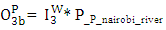

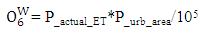

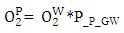

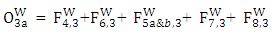

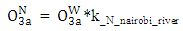

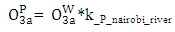

According to Fig.5, there are four outflows from the boundary system; O6 is the outflow from the urbanized area due to ET, O2 is outflow due to groundwater export to the peri-urban areas, O3a and O3b are surface water outflows due to system boundary discharge into the Nairobi River and the river upstream flow, respectively. The ETof rainfall within the system boundary is the only flow that transports water but no pollutants.  | (75) |

| (76) |

| (77) |

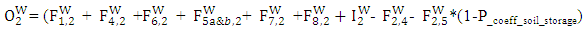

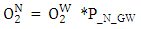

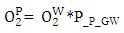

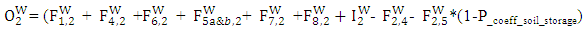

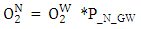

Groundwater export from the aquifers was estimated as: | (78) |

| (79) |

| (80) |

Outflow due to the discharge from the urbanized area and other compartments of the boundary system: | (81) |

| (82) |

| (83) |

| (84) |

| (85) |

| (86) |

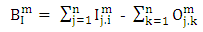

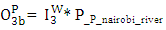

3.13. Mass Balance

3.13.1. Mass Stock Exchange

The stock change for a one year period for all boxes is assumed zero. However, in the short-term, soils and aquifer store some moisture which was reflected as a mass stock change. The stock change for all processes was defined as the mass balance of inputs minus outputs. | (87) |

n = 10, m=W, N and P, j=number of box; i= box of origin and k = destination box.Stock change of boxes was denoted as  , with i=number of box, and m=W, N, and P. The definition of each of the stock exchange was herein explained, thus:WaterThe mass stock exchange for water (W) box1 (Fig. 5) gets incorporated in the treatment plant, gets lost through ET or infiltrated. However, stock change data was not available and therefore only outflows were considered in the computations.Nitrogen and Phosphorous

, with i=number of box, and m=W, N, and P. The definition of each of the stock exchange was herein explained, thus:WaterThe mass stock exchange for water (W) box1 (Fig. 5) gets incorporated in the treatment plant, gets lost through ET or infiltrated. However, stock change data was not available and therefore only outflows were considered in the computations.Nitrogen and Phosphorous Accumulation of immobile N and P in the top-soil layer. Part of the N stock is lost to the atmosphere, another part to runoff.

Accumulation of immobile N and P in the top-soil layer. Part of the N stock is lost to the atmosphere, another part to runoff. Consumption of N by processes such as de-nitrification, ammonia, volatilization and to lesser extent, sediment mineralization and plant incorporation. Some P is adsorbed to clay particles or bound to metallic compounds.

Consumption of N by processes such as de-nitrification, ammonia, volatilization and to lesser extent, sediment mineralization and plant incorporation. Some P is adsorbed to clay particles or bound to metallic compounds. input from imported pollutant sources such as industrial wastes.

input from imported pollutant sources such as industrial wastes. that results from excrements and organic wastes with a large fraction of P stock exchange emanating from detergents.

that results from excrements and organic wastes with a large fraction of P stock exchange emanating from detergents. that results from organic wastes within the urbanized area.

that results from organic wastes within the urbanized area. accumulating from buried fecal sludge.

accumulating from buried fecal sludge. that accumulates from the fecal sludgein the WWTP, the stabilization ponds call for regular desludging.

that accumulates from the fecal sludgein the WWTP, the stabilization ponds call for regular desludging.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Modal Plausibility

Sensitivity analysis of some parameters was underatken to establish how sensitive they were to changes in the model performance. Sensitivity analysis was particularly important for scenario development for the modelled system. The most sensitive parameters were the fraction of treated wastewater from non-domestic users (P13, k_non_dom_treated) and the fraction of pipewater connection to non-domestic users (P10, k_pipe_non-dom). This sensitivity was mainly notable on N outflow from the system. Results discussed later showed that indeed the non-domestic water users produced the largest amount of N from the system. Knowledge of the sensitive parameters was important in monitoring the overall performance of the model and extreme care was to be taken when dealing with the two transfer coefficients. For example, concentration of N responded sharply with adjustment of the said two coefficients. However, alteration of other coefficients revealed small changes in the outflow indicating the model performance would still be relatively steady even with variation of the considered coefficients. But, the small changes in certain variables and coefficients should not be underestimated as model output may as well be dependent on variation in inflows.

4.2. Scenario Analyses

4.2.1. Scenario 1: Growth Scenario to 2030

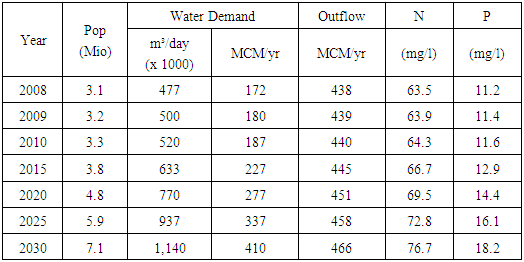

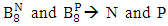

By 2030, the Government of Kenya envisages attaining the middle incomestatus. An ambitious program for implementation has been planned and was discussed in section 1. The implications of population growth on water quality and sanitation in response to this ambitious national development strategic plan are analyzed and discussed in this section. Scenario 2030 has been developed on this basis and visualizes possible future problems of water demand and endeavors to assess pipe water supply and the role groundwater and other water sources such as rainwater harvesting will play to cushion the deficits. It further, analyses the probable water quality and pollutant generation by the increased developments and population levels. The FAO and EPA recommend maximum levels in effluents at 10 mg/l and 2 mg/l for N and P, respectively [12, 23]. Growth scenario 2030 anticipates more jobs and improved economy and quality of life. The implication is that the population will keep growing with life pressures pushing an increase in rural-urban migration to city in search of greener pastures. However, it is possible for the government to counter any negative impacts if sound economic and proper infrastructure development strategies are implemented, including those on good water and environmental management., which is the focus of this study.Case 1: Influence of population growth and investments, other factors remaining constant with no improvement on the current infrastructure status. The water demand and nutrients generation because of this case scenario are summarized in Table 3.Table 3. Impact of population growth

|

| |

|

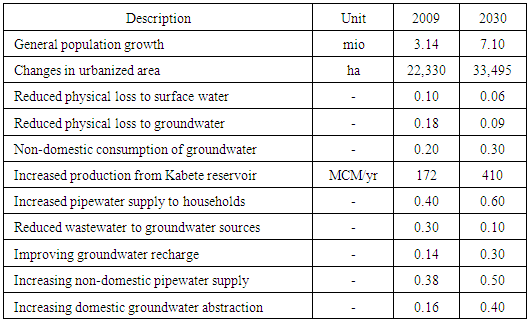

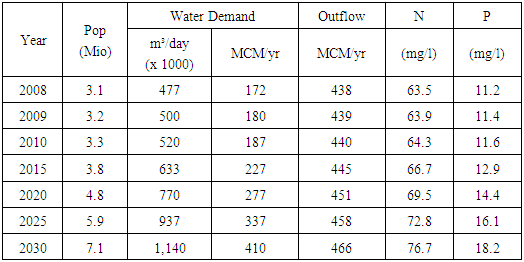

According to NWSC (2008, personal communication), the total average daily water production is 476,603 m³/day which was assumed to suffice the current water demand needs. This value was adjusted to include losses (Table 2) and formed the baseline for model projection. The model prediction showed that by 2030, 1.1 MCM/day of water would be required in the city, translating into 410 MCM/yr. This value provides for continued per capita consumption of 60l/ca.day, investments and other non-domesticusers. In reality, with the economic and improved living standards projected by vision 2030, per capita water demand would be expected to increase. The population in 2030 is expected to rise to over 7 million at the current city growth rate of about 4% per annum [5] mainly due to rural-urban migrations and increase in investments. It means more than 4 million people are expected to move into the city. Implications of this scenario (Table 3) will result in 160% (238 MCM/yr) increase in water demand by 2030. Based on these changes, the corresponding substance concentrations flowing into the environment are projected to increase from the present emissions of approximately 63 mg/L N and 11 mg/L P to 77 mg/L N and 18 mg/L P by 2030, respectively. The increases in N and P concentrations are by 13 mg/L N and 7 mg/L P, respectively.Case 2: Additionally, the projected increase in N and P are also based on the fact that the boundary of the City of Nairobi as envisioned to expand. Thus, the scenario assumes that there will be an increase of groundwater contribution of 40% of total domestic consumption up from the current contribution of approximately 16%, physical and illegal connections losses will be reduced to 15%, the increase in the urbanized area is expected to be by at least 50% from 22,330 ha to 33,495 ha, increase in non-domestic groundwater consumption to rise from0.2 MCM/yr to 0.3 m3/yr, while the groundwater recharge will improve from 0.14 to 0.3 through increased infiltration.The above assumptions were taken with a view that for the country to reach a middle level industrialized status as envisaged in the government Vision 2030 report, certain measures are important to ensure a sound socio-economic, environmental and improved water supply.Generally, for economic growth in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors, adequate water supply is critical. At the same time, increasing population demands that other sources of water abstraction from safe sources should be provided such as groundwater which is highly under-utilised in Nairobi. To ensure enhanced water supply would also require reducing physical losses and while increasing piped water supply. The corresponding adjusted parameters and coefficients associated with these changes are summarized and reported in Table 4.Table 4. Adjusted parameters and coefficients for scenario 2030

|

| |

|

Whereas the increase in the drinking water supply is necessary to protect the city against future water crisis, such an increase may be unsustainable unless certain technologies are put in place to reduce daily demand. Presently, water supply in Nairobi is from a distant 50 km from the city centre and new sources will need to be explored. Climate change introduces additional uncertainities into the regions’ water supply situation, which this study does not a dress. The double digit economic growth rate forecast by the authorities (according to vision 2030) may be unattainable unless careful plans are developed and implemented. Wastewater generation is bound to increase substantially due to increase in water demand mainly from domestic and non-domestic waters users. Running the model with the changes in Table 4 showed that with the increased water use, the rise in wastewater increase by 125% will result because of the population increase within this period. The predicted annual untreated loads generated by such population explosion are projected to reach 173,600 t/yr N from the present 49200 t/yr N, while P will increase from 8,179 t/yr P to 27,660 t/yr P. The million dollar question is, are the authorities prepared to deal with this growth explosion? Even with smart ways of attracting donor funds, how sustainable are we able to address such a grave situation?. Currently, wastewater treatment in Nairobi is via lagoons with most of collected sewage lost into the environment through sewer overflows and leakages due to an inadequate and aging sewer system.

4.2.2. Scenario 2: Implications of Implementing Different Sanitation Technologies “Scenario Toilet”

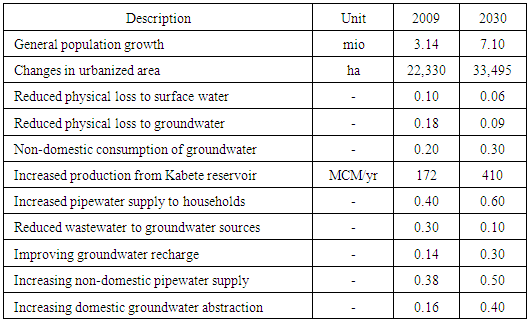

This scenario explored the influence of implementing different sanitation technologies on the changing water demand and change in substance flows as compared to the baseline levels. The scenario attempted to answer the question: what is the influence of reduced use of wet sanitation and increased use of dry sanitation on water consumption and pollutant flows? The current sanitation facilities and their distribution in Nairobi are appalling. In some exceptional cases such as slums, as many as 500 people share a single unhygienic traditional pit. Theoretically, the use of water closets (WCs) stands at 66%, of which only 40% are connected to the sewer lines (NWSC, 2008, personal communication). However, the reality of WC use may not be intandem with these figures and a detailed investigation is vital to ascertain the true position. The estimated fraction of people using traditional pits is 27%, VIP toilets stands at 2%, open defecation 3% and other 2% [24]. In the recent past, there has been an effort by the Nairobi City County Government to provide pay toilets a cross the City. The unreliability of water supply in the city increases each day, and this situation is exacerbated by climate change that causes draughts and drying of water reservoirs. Its implication is such that future use of wet sanitation systems is problematic, necessitating a paradigm shift to dry sanitation system. The following hypothetical developments (Table 5) were thus, proposed and evaluated.Table 5. Adjusted variables for the scenario "toilet"

|

| |

|

Compared to the status quo, implementing the proposed developments resulted in reducing grey water generation by 5%, from 74 MCM/yr to 69 MCM/yr by 2030. Blackwater flow to soils and aquifers was reduced by 70% from 9 MCM/yr to 3 MCM/yr. Despite the population increase to over 7 million people, only 1.4% of untreated blackwater was oberved to flow directly to surface water with implementation of this scenario. A careful implementation of dry sanitation could still further bring down the wastewater emissions. The greatest impact of the development scenario toilets was seen on reductions in N and P loads. The N and P loadings to surface waters were reduced by 62% and 45%, respectively. To the soils and aquifers, the reduction was 83% N and 85% P. Generally, reduction of N and P loadings to surface and groundwater sources are 80% N and 71% P, respectively. In terms of concentrations at the downstream of Nairobi River, N was 49.5 mg/L N and 9.85 mg/L P; a 36 and 45% reductions in N and P as compared to the levels in scenrio 1 case 1. Compared to baseline concentrations in the Nairobi River, the reductions were 21 and 10% for N and P, respectively.

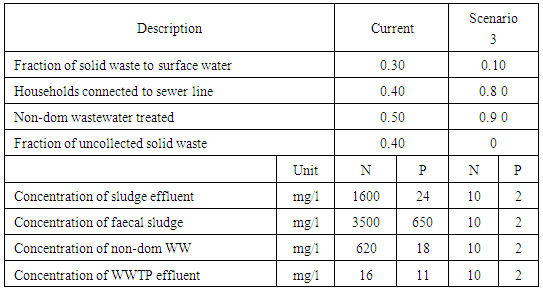

4.2.3. Scenario 3: Improved Wastewater Treatment and Solid Waste Management

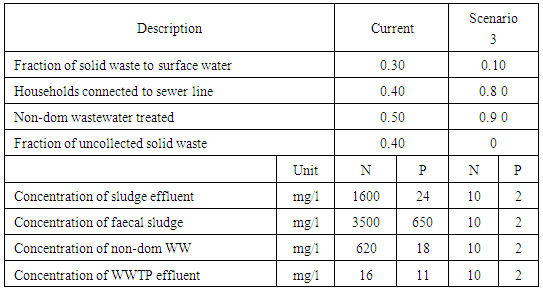

This scenario was developed to reduce substance flows to surface water through improved ways of treating wastewater and management of solid wastes. The scenario focused on reducing pollution of surface water; hence only pollutants were simulated and discussed. Scenario 3 implemented N and P according to the recomended common water quality parameters and proposed EPA guidelines for maximum values [12, 23, 25, 26]. Table 6 highlights relevant parameters and transfer coefficients hypothesised for improved effluents to surface water.Table 6. Adjusted parameters for scenario waste

|

| |

|

Implementing this scenario significantly reduced N concentration by 75% (60 mg/L N to 15 mg/L N) and P value by 60% (10 mg/L P to 4 mg/L P), respectively in the Nairobi River. These concentrations would still be sufficient to cause eutrophication in the Nairobi River. The loadings to the soils and aquifers were reduced by similar margins. Reduction of pollutant loads from the untreated greywater to surface water changed by 88% N (166 to 18 t/yr) and 40% P (975 to 589 t/yr). Infiltration of blackwater loads remained the same since no improvement on their handling is proposed by the scenario. However, effluent from disposed sludge to surface water was reduced by 99% N (11 to 0.06 t/yr) and 100% P transformation, with similar trend to soils and aquifers. Meanwhile, WWTP effluent loads to soils and aquifers reduced by 15% N (260 to 223 t/yr) and substantially by 745% P (178 to 45 t/yr). For surface water loadings, the scenario reduced WWTP loads of N and P by 14% (2,347 to 2,011 t/yr), and 75% (1,602 to 402 t/yr), respectively. The 100% garbage collection drastically improved the stormwater quality; reducing surface water loads by 84% N (1,690 to 275 t/yr) and 95% P (800 to 27 t/yr). Infiltration of stormwater contributed to a 88% N reduction (882 to 105 t/yr), and 91% P reduction (358 to 32 t/yr) compared to their original values.

4.2.4. Combining Scenarios 2 and 3

When all these scenarios were combined while considering the predicted population increase and expansion of the city by 2030, resulting N and P concentrations were 12 mg/L N and 4 mg/L P, respectively in the Nairobi River. While still at eutrophication levels, these results showed that with good planning, financial back-up and proper implementation, the scenario technologies can control excessive emissions into the water bodies and the environment. If investments are carefully directed towards sustainable water quality and management projects, projected environmental degradation may be reduced. However, an increase in water-borne sewerage may not be sustainable with increasing pressure on water and environmental resources.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The City of Nairobi will experience unparalleled population growth that far exceeds its absorptive capacity in terms of water, sanitation infrastructure, public health and environmental protection. These challenges require implementation of sustainable environmental protection technologies. These will ensure provision of sanitation infrastructure while conserving water especially in the densely populated urban informal developments.The FAO and EPA recommend maximum levels in effluents at 10 mg/l and 2 mg/l for N and P, respectively [12, 23]. Results from this study showed that the concentrations of N and P were: status quo - 63 mg/L N, 11 mg/L P; scenario one (2030 population growth with current practices): 77 mg/L N, 15 mg/L P; scenario two (increased use of dry toilets): 50 mg/l N and 10 mg/L P; and scenario three (improved wastewater treatment and solid waste management): 15 mg/L N, 4 mg/LP. The effects of combining scenarios 2 and 3 on the effects of population explosion by 2030 was seen to maintain N and P at 12 and 4 mg/L, respectively. Combining the two scenarios can keep emission levels at near FAO and EPA recommended levels in surface water of 10 mg/l and 2 mg/l for N and P, respectively. The guideline receiving water standard for Kenyan waters is 2 mg/1 for N and P, respectively. The need for good environment conservation would yield good results, and this is possible through involving the entire community, creating awareness and the pollution producers such the corporate community playing a leading role in conservation and social responsibility. This can simply be referred to as effective participation of all stakeholders. Further, for elated results in load reductions it is recommended that the city authorities invest more in simplified sewerage systems in the high density areas, implement latrines in the medium-density areas and central/communal facilities in densely populated areas. Additionally, encourage use of flush systems and septic tanks in the high-cost and low density areas would be ideal. Construction of public facilities should be encouraged in markets, schools and light industrial areas locally known as “jua-kali sector”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported through funding from the German Academic Exchange Program (DAAD), Germany. Further, the author appreciates the support provided by Marco Erni (Eawag, Switzerland), Pay Dreschsel (IWMI, Sri Lanka), Prof. Emeritus Theo Dillaha (Virginia Tech) and Dr.-Ing. Jens Traenckner and Prof. Dr. Sc.techn. Peter Krebs both of Institute of Urban Water Management TU-Dresden, Germany.

References

| [1] | Tibaijuka, A., 2007. Chapter 5: Nairobi and its Environment, in Kenya Atlas, J. Barr and C. Shisanya, Editors. UNEP/ UNHABITAT. |

| [2] | GoK, 2010. The Constitution of Kenya.. Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya. |

| [3] | CCN, 2007. City of Nairobi Environment Outlook. City Council of Nairobi. United Nations Environment Programme and the United Nations Centre for Human Settlement.. |

| [4] | Mitullah, W., 2003. Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements 2003: The Case of Nairobi, Kenya, 2003, UNHABITAT, Nairobi. |

| [5] | KNBS, 2015. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.Available: www.knbs.go.ke. |

| [6] | Alukwe, I.A., 2008. Urban Drainage and Sanitation in Fast Growing African Mega Cities: Status Quo and Development Scenarios. (A case study of Nairobi, Kenya), in Faculty of Forest, Geo and Hydro Science. Dresden University of Technology, Germany. |

| [7] | Montangero, A. Material Flux Analysis (MFA) for Environmental Sanitation Planning. An Introduction Lecture Notes and Exercises. 2006, Bangkok. |

| [8] | Huang, D., 2006. Confronting limitations: New solutions required for urban water management in Kunming City. Journal of Environmental Management. |

| [9] | Baccini, P. and H.P. Bader, 1996. Regionaler Sto_haushalt, Erfassung, Bewertung und Steuerung, Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg. |

| [10] | Erni, M., 2007. Modelling urban water flows: An insight into current and future water availability and pollution of a fast growing city. Case Study of Kumasi, Ghana. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, Switzerland. Available:http://e-collection.library.ethz.ch/eserv/eth:29522/eth-29522-01.pdf. Accessed Aug. 3, 2014. |

| [11] | EEA, 2003. Europe’s Environment: The third Assessment. Environmental assessment report, Europeans European environmental agency: Copenhagen Denmark. |

| [12] | WHO/FAO/UNEP, 2006. Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater. World Health Organization - WHO-FAO-UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland. |

| [13] | WB, 2002. The world development indicators. World Bank: Washington DC USA. |

| [14] | Magoba, 2008. Data on water demand, distribution and wastewater treatment. NWSC, Nairobi Kenya. |

| [15] | DN, 2003. 500 Ghost workers removed from payrollsays Kidero, in Daily Nation, Nation Media Group: Nairobi. |

| [16] | Milam, R.D., 1998. Run-off coefficient factsheet. Available: www.geocities.com/Eureka/Concourse/3075/Coef.html. |

| [17] | Foster, S. and A. Tuinhof, 2005. Kenya: The Role of Groundwater in the Water-Supply of Greater Nairobi, Sustainable Groundwater Management Lessons from Practice GW-MATE. World Bank. |

| [18] | CBS, 2006. Economic SurveY. Central Bureau of Statistics: Nairobi. |

| [19] | KNBS, 2008. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. http://www.knbs.go.ke/. |

| [20] | IEBC, 2012. Preliminary report on the first review relating to the delimitation of boundaries of constituencies and wards Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission: Nairobi. |

| [21] | Ahn, C.H. and R. Tateishi, 1994. Monthly potential and actual evapotranspiration and water balance. United Nations Environment Programme/Global Resource Information Database, Dataset GNV183. |

| [22] | EPA. 1992. Environmental Protection Agency. Available: www.epa.gov. |

| [23] | CBS, 2002. Central Bureau of Statistics. Available: www.knbs.go.ke. |

| [24] | FAO, 2005. Fertilizer use by crop in Ghana. Land and plant nutrition management service land and water development division. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations: Rome. |

| [25] | NEMA, 2003. State of the Environment Report for Kenya. |

, for j = W, N and P.Where: W = water for all balance volumes n, N = total nitrogen, P = total phosphorous. All mass flows were developed based on the schematic in Fig. 5.The different inflows into the system boundary relate to inputs of the considered parameters (Table 1 and 2). Where necessary, units were converted using conversion factors to form the stated units in the results. The inflow into the urbanized (developed) area was mainly as a result of rainfall and atmospheric deposition of N and P as follows:

, for j = W, N and P.Where: W = water for all balance volumes n, N = total nitrogen, P = total phosphorous. All mass flows were developed based on the schematic in Fig. 5.The different inflows into the system boundary relate to inputs of the considered parameters (Table 1 and 2). Where necessary, units were converted using conversion factors to form the stated units in the results. The inflow into the urbanized (developed) area was mainly as a result of rainfall and atmospheric deposition of N and P as follows:

, with i=number of box, and m=W, N, and P. The definition of each of the stock exchange was herein explained, thus:WaterThe mass stock exchange for water (W) box1 (Fig. 5) gets incorporated in the treatment plant, gets lost through ET or infiltrated. However, stock change data was not available and therefore only outflows were considered in the computations.Nitrogen and Phosphorous

, with i=number of box, and m=W, N, and P. The definition of each of the stock exchange was herein explained, thus:WaterThe mass stock exchange for water (W) box1 (Fig. 5) gets incorporated in the treatment plant, gets lost through ET or infiltrated. However, stock change data was not available and therefore only outflows were considered in the computations.Nitrogen and Phosphorous Accumulation of immobile N and P in the top-soil layer. Part of the N stock is lost to the atmosphere, another part to runoff.

Accumulation of immobile N and P in the top-soil layer. Part of the N stock is lost to the atmosphere, another part to runoff. Consumption of N by processes such as de-nitrification, ammonia, volatilization and to lesser extent, sediment mineralization and plant incorporation. Some P is adsorbed to clay particles or bound to metallic compounds.

Consumption of N by processes such as de-nitrification, ammonia, volatilization and to lesser extent, sediment mineralization and plant incorporation. Some P is adsorbed to clay particles or bound to metallic compounds. input from imported pollutant sources such as industrial wastes.

input from imported pollutant sources such as industrial wastes. that results from excrements and organic wastes with a large fraction of P stock exchange emanating from detergents.

that results from excrements and organic wastes with a large fraction of P stock exchange emanating from detergents. that results from organic wastes within the urbanized area.

that results from organic wastes within the urbanized area. accumulating from buried fecal sludge.

accumulating from buried fecal sludge. that accumulates from the fecal sludgein the WWTP, the stabilization ponds call for regular desludging.

that accumulates from the fecal sludgein the WWTP, the stabilization ponds call for regular desludging. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML