C. O. Odudu

Department of Estate Management, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

Correspondence to: C. O. Odudu, Department of Estate Management, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

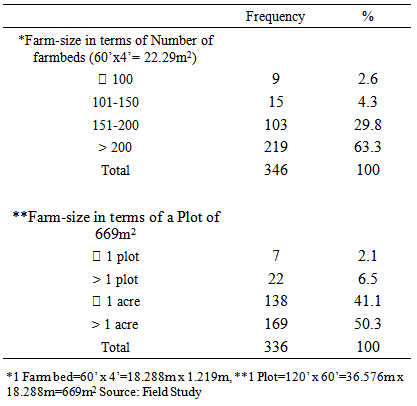

Inefficient economies and poor governance precipitate factory closures, retirements, growing unemployment thereby stimulating growth of crop farming in towns and cities of developing countries. The study evaluates the entrepreneurial ability of urban crop farmers, identifying issues that can be resolved in order to benefit from entrepreneurship of the urban crop farmer in the Lagos metropolis. Crop farmers in some locations where urban crop farming was found to be thriving within the Lagos Metropolis were selected through simple random sampling and questionnaire administered on them. Data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics while one-way analysis of variance test was used to investigate the research hypothesis. The study established that there was dexterity by urban crop farmers to go into large-scale or market-oriented farming to generate more income. Also, 63.3% of famers cultivated over 200 farm beds while only 2.6% cultivated less than 100 farm beds. The study concluded that tapping the entrepreneurial ability of urban crop farmers was a veritable source of poverty alleviation, food security and income generation and that land be zoned for the activity in specified areas for medium to long-term lease periods to enhance farmers’ productivity.

Keywords:

Entrepreneurial ability, Entrepreneurial agriculture, Urban crop farming, Urban agriculture, Lagos, Nigeria

Cite this paper: C. O. Odudu, Tapping the Entrepreneurial Ability of Urban Crop Farmers in Income Generation in Lagos, Nigeria, American Journal of Environmental Engineering, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 155-161. doi: 10.5923/j.ajee.20140406.03.

1. Introduction

Urban crop farming is generally land-based and recognized worldwide as a farming practice in the towns and cities of both developing and developed countries. The term is used interchangeably with urban agriculture and urban farming in this study. This phenomenon pervades major cities of the world prompting a report which estimated that between 15 and 20% of the world’s food is produced by some 800 million urban and peri-urban farmers and gardeners. [1] Participation in urban agriculture is open ended as it is not limited to agriculture professionals or wealthy entrepreneurs but has been found to be a haven to retirees either on disengagements from place of work due to old age or young persons retired as fallout of the effects of the various structural adjustment programmes. It has also been found as a veritable source of employment for women in households as urban farming either supplements their nutritional needs or as a source of additional income. [2] A common precipitate of urban farming especially in developing countries is the poor state of most of the economies. In the early 1980s, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) pet-programme or panacea for ailing economies, the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) was introduced by most of the developing countries whose economies were most hit by global recession. The programme brought in its wake massive devaluation of the local currency in favour of currencies of the developed countries led by the US$ and the British pound sterling. The story of SAP was the same everywhere whether in Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda or Kenya. For example, it was noted that by the early 1990s, most African countries were implementing structural adjustment programmes (SAPs), implying, amongst others, drastic cuts in public expenditures, trade liberalization, increased interest rates and devaluation. [3] The consequences of the devaluation of local currencies were obvious loss of jobs by locals and withdrawal of expatriate services as most industries became characterized by low capacity production and outright closures. Thus, personnel were retired from the civil service, private sectors as well as the military which opened the doors into urban agriculture particularly urban crop farming. Entrepreneurial urban farming which encompasses more economic-oriented farming can be family-based and is run by private investors or producer associations. This is still poorly developed because of numerous hindrances especially lack of access to land for the expansion of urban farming in towns and cities. The high population of Lagos state (over 18 million people as claimed by the Lagos State Authorities) creates a high demand for land for various uses ranging from residential, commercial to industrial uses. Land as an important factor in urban food production is outside the reach of the farmers as they are generally poor and are unable to afford or compete with other uses for land. [4] The study therefore, conceptualizes that urban crop farming has a lot of potentials that can be tapped for the benefit of the teeming unemployed youths and poses the question on what determines income generation in urban crop farming. The study will also resolve the hypothesis that, “there is no significant difference in crop farmers’ income and their farm-size”. The paper has five parts. The first part introduces the subject matter, the second part concepts and issues, the next part research methodology, the fourth part the result of data analysis while the final part is conclusion and recommendations.

2. Concepts and Issues

2.1. Entrepreneurship of the Urban Crop Farmer

The entrepreneurial status of urban crop farming has hardly been discussed in literature as most have continued to link precipitating factors of urban crop farming to deteriorating national economies particularly the economies of developing countries. [5] An earlier attempt to link urban farming to entrepreneurial or market-oriented strategy was the comparative study of the activity in Lagos and Port Harcourt. [6] The study identified commercial vegetable producers in metropolitan Lagos who invested in labour for land preparation, planting, weeding, irrigation and harvesting. This therefore prompted the question whether urban farmers required special skills or should they be rigorously tutored in agricultural practices or should they acquire entrepreneurial ability for purposes of urban crop farming? It was noted that skill was the means by which man adjusted to life and therefore a thing he acquired in pursuance of his life processes or working life and on retirement needed new skills on how to enjoy his leisure and adjust in his new way of life. [7]. Other literature showed that urban crop farmers were mainly retirees and poorly educated [8] while some others were educated. [9] The urban crop farmer is undoubtedly an entrepreneur who has decided to take control of his/her future and become self employed whether by creating his own unique business or working as a member of a team at a multi level vocation. He is a person who has possession of an enterprise or venture and assumes significant accountability for the inherent risks and the outcome. He is an ambitious leader who combines land, labour and capital to create and market new goods or services. [7] Thus, the urban crop farmer possesses those entrepreneurial skills that are enabling him/her to succeed in the activity and hence the rising number of entrants into the activity in towns and cities. It was stressed that most of the past studies had mainly focused on livelihoods of poor urban dwellers [10] while some other studies linked it with urban poverty, poverty alleviation as well as income and employment generation. [11] It was further claimed that urban farming was probably developing in a context of innovation and dynamism beyond dire poverty and that lack of this understanding could have negative implications for urban management and urban development. [10] It was, however, noted that there was little distinction in the literature between the growth of urban agriculture as a household strategy and the growth of urban agriculture as an entrepreneurial strategy. [10] A study conceptualized policy dimensions and main types of urban farming such as market-oriented urban farming where large scale entrepreneurial enterprises are practised. [4] The bane of entrepreneurial agriculture is however, lack of access to quality land for the activity. It was further reaffirmed that the activity of urban farmers was highly affected by lack of access to land and insecure documents thereby discouraging investment in the activity. [6] Owing to lack of financial resources to acquire land, urban crop farmers are found to be farming on marginal lands that are unproductive. Thus, practitioners of entrepreneurial agriculture are faced with numerous constraints such as lack of capital, lack of fertilizers, agrochemicals and labour/farmhands among various constraints. It was further established that inputs had a positive relationship with farmers’ productivity, that is, the use of shallow well water and poultry wastes made cultivation less expensive and farmers more productive. [12] Thus, lack of access to land has ripple effects on urban farmers’ investments and productivity. The study was therefore carried out as examined in the next part.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

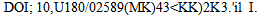

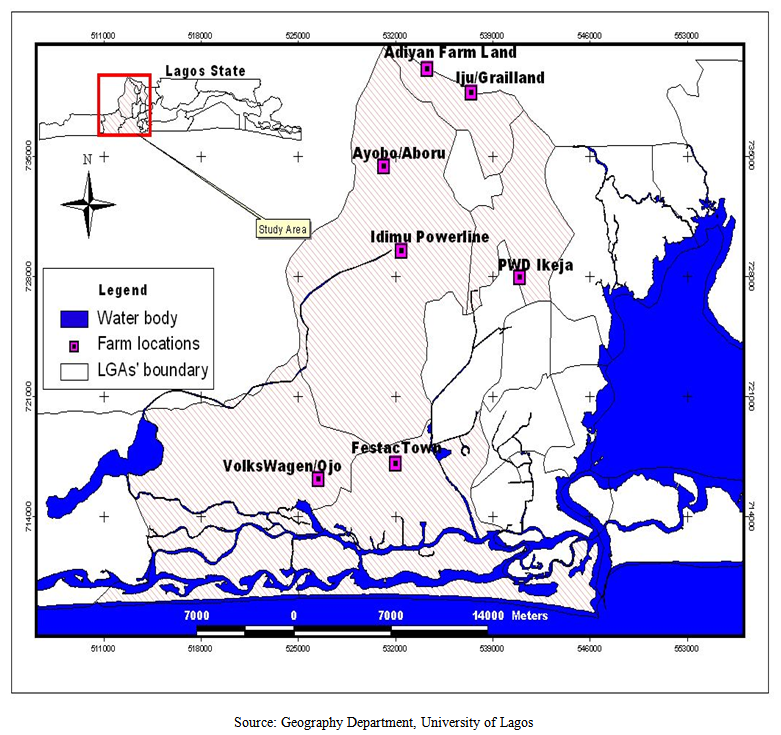

The study is limited to metropolitan Lagos which is home to many companies and industries and located in the south-western part of Nigeria. The boundaries of metropolitan Lagos are defined as consisting of the territory within Latitudes 6° 23’ N and 6° 41’ N and Longitudes 3° 09’ E and 3° 20’ E. [13] It is also noted that the Lagos lagoon stretches through the eastern boundary; bounded in the south by the Atlantic Ocean while the northern boundary has the landmass of Ikorodu local government area and Alagbado towards Abeokuta axis in Ifako-Ijaiye local government area. Badagry and Republic of Benin define the Western boundary. [14] Metropolitan Lagos constitutes over 1,140km2 (or one-third) of the total land mass (3,577km2) of Lagos State. Lagos has since ceased to be Nigeria’s capital but still has great impact on the nation’s economic development. It is still the commercial nerve centre of Nigeria as more than half of Nigeria’s industrial capacity is located here. In the post-structural adjustment programme (SAP) era, many of the companies and industries closed business and this led to continuous retrenchments by both private and public sectors, thus, increasing the population of people in the informal sector as well as making metropolitan Lagos a good location for this study. The pressure on land by the various uses is over-whelming and distribution of land in the metropolis is relatively uneven against urban crop farming. As regards spatial distribution of urban farming communities, the Lagos State Agricultural Development Authority (LSADA) demarcated Lagos State into three agricultural blocs as eastern, western and far western blocs. The western bloc which lies within the Lagos metropolis has a high population of urban crop farmers distributed in ten agricultural circles and each circle consisting of three cells or farming communities. Communities identified included Adiyan, Iju/Grailland, Ayobo/Aboru, Idimu/Powerline, PWD Ikeja, Volkswagen/Ojo and Festac Town. (See Figure 1).

3.2. Methodology

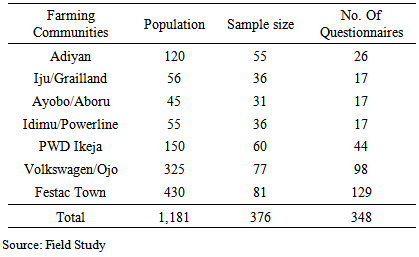

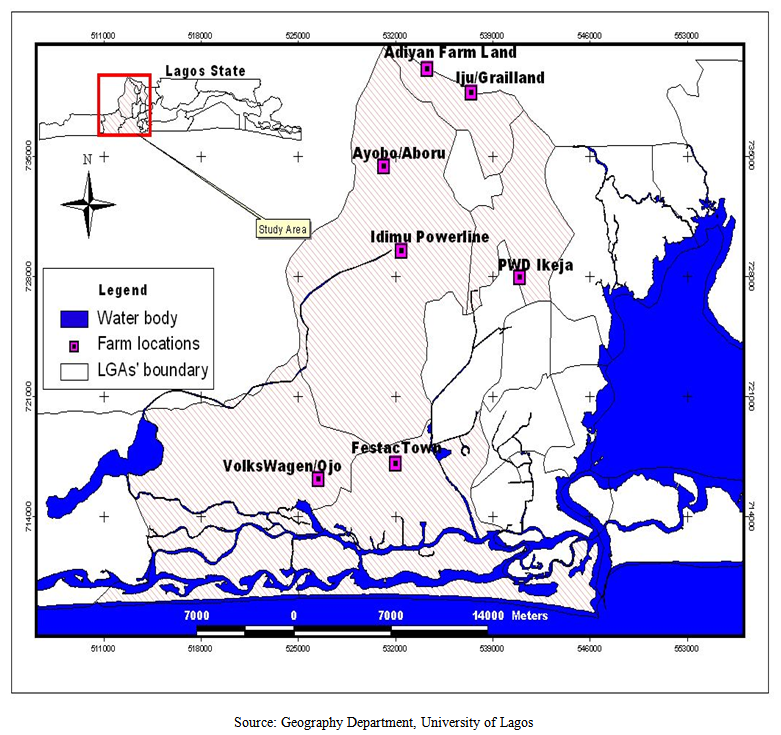

The study population consisted of all the practitioners of urban crop farming in the study area as contained in the register of the Lagos State Agricultural Development Authority in respect of the western agricultural bloc (Fig. 1). Multi-stage sampling was adopted for the selection of sample size because of the complexity of the population of farmers which was distributed all over the Lagos metropolis. Purposive sampling was firstly used in this study to select seven agricultural circles from the ten circles in the metropolis. Secondly, a cell or farming community was randomly selected from each circle of three cells. This gave a total of seven farming communities. Lists of registered urban crop farmers in each farming community were obtained from the Lagos State Agricultural Development Authority Headquarters in Oko-Oba, Agege to enable the determination of the sample size in each farming community (Fig. 1). The elements or respondents in each farming community were selected through simple random sampling from each stratum. Thus, the sample size for each population of farmers in a farming community was determined using an equation [15, 16] which noted as follows: | Figure 1. Metropolitan Lagos Showing the Study Locations, 2012 |

N = n’ [1 + (n’/N)]Where:N = total population (of each farming community) is recorded in the registern = sample size from finite populationn’ = sample size from infinite population calculated from the formula [n’=S2/V2] in which,S2 = standard error of population elements, S2 = P (1-P); maximum at P = 0.5V2 = standard error of sample population equals 0.05 for the confidence level of 95%=1.96n’ = S2/V2 = (0.5)2/ (0.05)2 = 100. Presented in Table 1 is the sample frame, sample size and questionnaires returned by the farmers. Copies of structured questionnaire were administered to a total of 376 respondents in the farming communities. Interview schedules with the farmers were carried out by the researcher and eight extension officers of the Lagos State Agricultural Development Authority which took place during meeting days of the various farming communities. The questionnaires administered on each farming community consisted of structured close-ended questions which requested, information on location of farm, size of farm, quantity of crops produced, problems of land accessibility, ownership, methods of accessing land, rent paid (if any), land purchase price and perception on government efforts and support for urban crop farming. Data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency, bar graphs and percentages to answer the research question while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to investigate the research hypothesis. Table 1. Urban farmers’ population, sample size and response rate

|

| |

|

4. Findings and Discussions

This section presents data collated from the field study, data analysis, hypothesis testing and discussions.

4.1. Level of Income Generation of Farmers

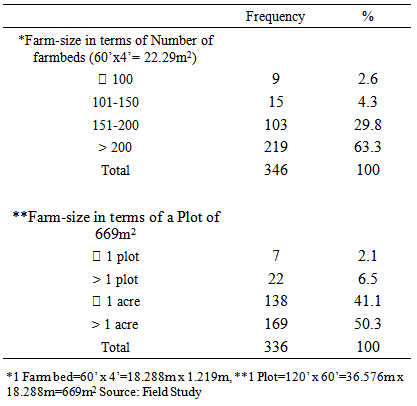

The study evaluated farmers’ capacity in terms of their entrepreneurial ability to explore farm land and carryout farming activities. The study established that the number of farm beds was increasing with an increasing number of farmers cultivating them. That is, only 2.6% cultivated less than 100 farm beds while 63.3% cultivated over 200 farm beds. The study further confirmed that 2.1% farmers cultivated small-sized farm lands or less than one plot while 50.3% cultivated farm lands of over one acre. These findings implied the willingness of urban crop farmers to undertake large-scale or market-oriented urban farming which agreed with other studies. [9, 3] See Table 2.Table 2. Farm-size

|

| |

|

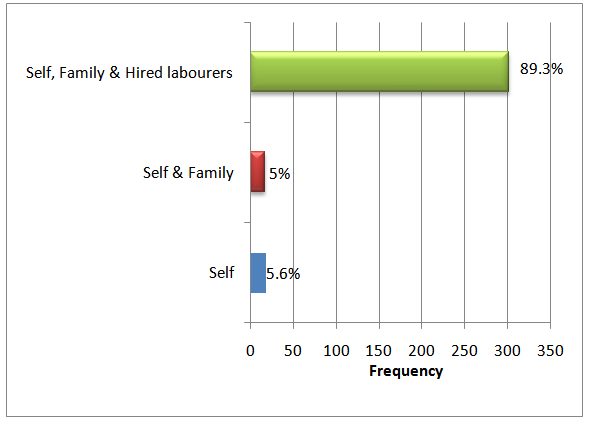

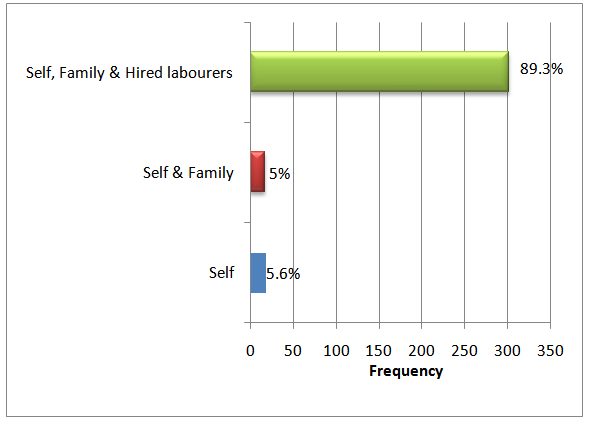

Fig. 2 further corroborated farmers’ desire and capacity to explore farming activities in the Lagos metropolis using types of workers on their farms. The study showed that less than 40 farmers (out of 320) engaged “self and family” workers or about 10.6% “self and family” workers on their farms while over 80% hired “labourers” on their farms in addition to “self and family” members.  | Figure 2. Type of Workers on Farm. Source: Field Study |

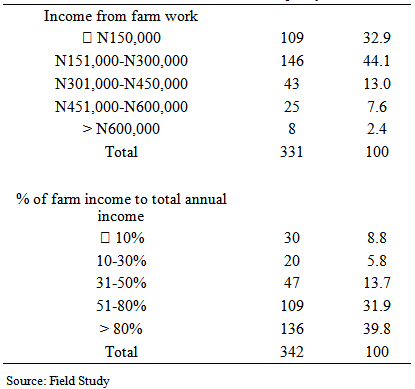

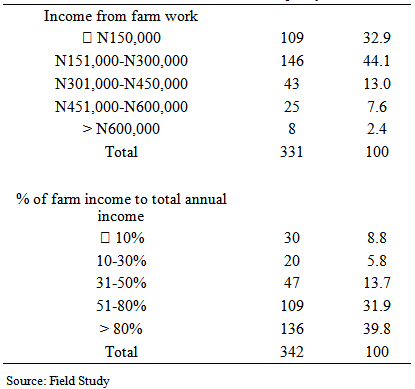

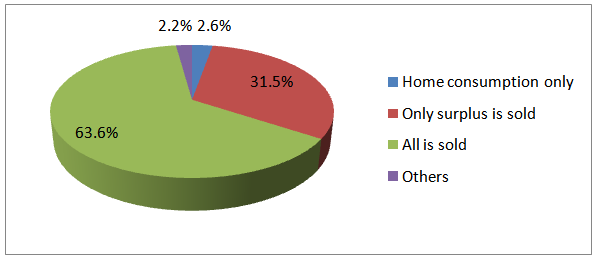

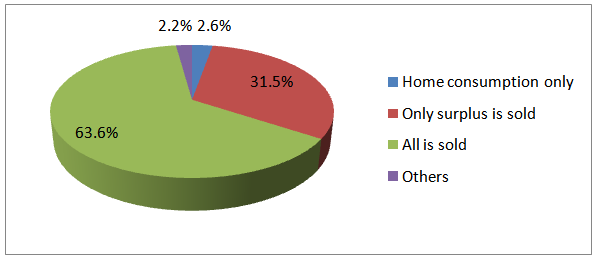

The income level of respondents was also used to evaluate the entrepreneurial strategy of farmers. The study showed that many farmers (57.1%) earned between N151,000 - N450,000 per annum, a few (8%) earned between N451,000-N600,000 per annum and a very few (2.4%) earned over N600,000 per annum. On the average, many farmers (44.1%) earned between N151,000-N300,000 annually. See Table 3. These findings implied that the farmers’ annual incomes were on a descending scale as over 70% earned more than 50% of total annual income from their farm produce. The study also showed that most farmers (63.6%) sold their farm produce for monetary exchange while only 2.6% produced for home consumption. See Figure 3.Table 3. Income Level of Crop Farmers

|

| |

|

| Figure 3. Use of Farm Produce. Source: Field Study |

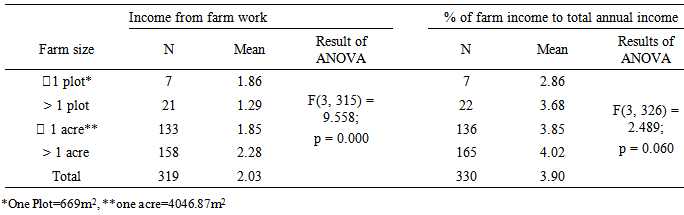

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

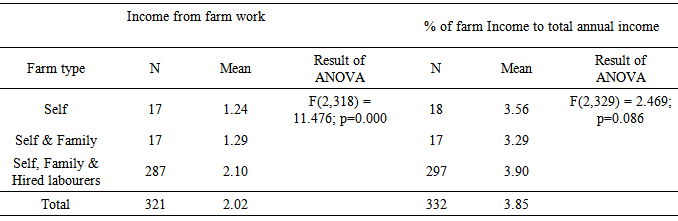

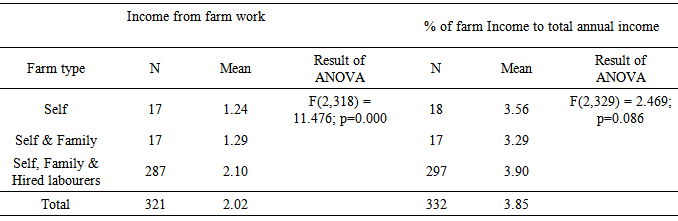

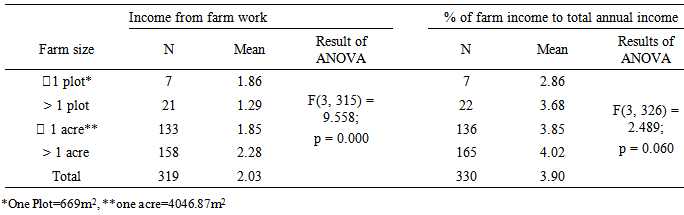

This study conducted a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test to investigate the research hypothesis that there was no significant difference in farmers’ income and their farm-size. Two sets of incomes, namely, (1) annual income from farm work, and, (2) percentage of farm income to total annual income were used. Also, two measures of farm-size were applied, viz, (1) based on type of workers, and, (2) based on plot-size.The study showed F-statistic to be significant (p=0.000, that is, p<0.01) enabling acceptance of the Alternative hypothesis that there was a significant difference in farmers’ income and their farm-size. This implied that more incomes were generated, the larger the farm-size in terms of type of workers or plot-size. The study also showed that high mean scores implied high incomes. Thus, income accruing to a farmer who used “self, family and hired labourers” (2.10 score) was higher than income accruing to a farmer who used “self” (1.24 score) or “self and family” (1.29 score) alone. Similarly, income from farms of more than one acre of land (with 2.28 score) were higher than those of smaller farm-sizes. These findings implied that crop farmers were quite desirous of going into large-scale or market-oriented urban farming agreeing with other studies. [4] It further implied that in spite of land accessibility constraints and lack of government support, there was still an urge by practitioners to go into urban crop farming. See Tables 4 and 5.Table 4. ANOVA Tests for Annual Income and Type of Worker on Farmland

|

| |

|

Table 5. ANOVA Tests for Annual Income and Plot-size

|

| |

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The study highlighted the importance of urban crop farming as a growing phenomenon in towns and cities of developing and developed countries. It discussed the prevalence of the activity particularly in developing countries as a consequence of poor economic measures resulting in an increasing number of retirees and the unemployed who invaded urban crop farming. It also noted the entrepreneurial nature of the activity and that the urban crop farmers were able to combine land, labour and capital to create and market new goods or services. The bane of the urban crop farmers was, however, lack of access to quality land for the activity. The study established that 63.3% of urban crop farmers cultivated over 200 farm beds while 2.6% cultivated less than 100 farm beds. It concluded that there was a dexterity by urban crop farmers to go into large-scale or market-oriented farming to generate more income. There was need for the Lagos state government to encourage more comparative data collection on urban crop farming to appreciate its contribution to poverty alleviation, food security and income generation. Although farmer network groups or farming communities were already existing as revealed by the study, these could be properly organized into formal network groups for social mingling after working hours, facilitate communications between government and farmers particularly in the introduction of scientific and technical improvements, enhanced social care for farmers and their families, fighting of HIV and AIDS and establishment of funds for productive and social investments. Government should therefore designate land use for the activity in specified areas for medium to long-term lease periods.

References

| [1] | United Nations-HABITAT. Land and sustainable food production. Presented at 2nd African Ministerial Conference on Housing and Urban Development, Abuja. Nigeria. July 2008. Retrieved 18/08/11 fromhttp://www.unhabitat.org/downloads/docs/amchud/bakg8.pdf. |

| [2] | Ashebir, D., Pasquini, M., and Bihon, W. 2007. Urban agriculture in Mekelle, Tigray State, Ethiope – principal characteristics, opportunities and constraints for further research and development. Cities, 24 (3), 218-228. Doi:10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.008. |

| [3] | Foeken, D.W.J., and Owuor, S.O. 2000. Urban Farmers in Nakuru, Kenya, Published by City Farmers, Canada’s Office or Urban Agriculture. Retrieved 06/03/04 from cityfarm@unixq.ubc.ca. |

| [4] | van Veenhuizen, R. 2006. Citiies Farming for the Future. In R.van Veenhuizen (Ed). Cities Farming for the Future. Urban agriculture for green and productive cities. International Institute for Rural Reconstruction and ETC Urban Agriculture. |

| [5] | Jacobi, P., Drescher, A.W., and Amend, J. 2000. Urban Agriculture–Justification and Planning Guidelines. City Farmer, Canada’s Office of Urban Agriculture. Retrieved 06/02/04 from cityfarm@unixq.ubc.ca. |

| [6] | Ezedinma, C., and Chukuezi, C. 1999. A comparative analysis of urban agricultural enterprises in Lagos and Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Environment and Urbanization, 11(2), 135-144. DOI: 10.1177/095624789901100212. |

| [7] | Adeyemo, S.A. 2009. Understanding and Acquisition of Entrepreneurial Skills: A Pedagogical Re Orientation for Classroom Teacher in Science Education. Journal of Turkish Science Education. 6(3), 57-65. |

| [8] | Odudu, C.O. 2009. Urban Agriculture as an ameliorating factor for Socio-Environmental problems. In T.G. Nubi, M.M. Omirin, S.Y. Adisa, H.a. Koleoso & J.U. Osagie (Eds.). Environmental Economics and Conflict Resolution. (pp.256-275), University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria. |

| [9] | Umoh, G.S. 2006. Resource Use Efficiency in Urban Farming: An Application of Stochastic Frontier Production Function. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, 8 (1), 38-44. Doi:1560-8530/2006/08-1-38-44. |

| [10] | Hovorka, A.J. 2004. Entrepreneurial Opportunities in Botswana: (Re) Shaping Urban Agriculture Discourse. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 22(3), 367-388.  |

| [11] | Reuther, S., and Dewar, N. 2005. Competition for the use of public open space in low-Income urban areas: the economic potential of urban gardening in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Development Southern Africa, 23(1), 97-122. doi:10.1080/03768350600556273. |

| [12] | Anosike, T.V. 2008. Poultry waste and shallow well water utilization implications on urban agriculture in Lagos metropolis (Unpublished Ph.D dissertation), University of Lagos, Nigeria. |

| [13] | Oni, S.I. 2001. Urbanization and Transport Development in Metropolitan Lagos. In M.O.A. Adejugbe (Ed),. Industrialization, Urbanization and Development in Nigeria 1950-1999 (pp.193-219). Concept Publications Ltd, Mushin, Lagos, Nigeria. |

| [14] | Olayiwola, L.M., Adeleye, O.A., and Oduwaye, A.O. 2005. Correlates of Land Value Determinants in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol., 17 (3). 183-189. |

| [15] | Kish, L. 1965. Survey sampling. New York, NY: Wiley. |

| [16] | Nirab, S. 2007. Investigation into Contractor’s bidding decisions in Gaza Strip, (Unpublished master’s thesis), Islamic University, Gaza Strip. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML