-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2025; 14(1): 6-9

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20251401.02

Received: Jan. 12, 2025; Accepted: Feb. 4, 2025; Published: Feb. 8, 2025

The Common Type of Facial Atrophic Acne Scars in Skin of Color

Mahdi M. A. Shamad1, Neama Motasem Abdelhai2, Nawaf AlMutairi3

1College of Medicine, University of Bahri, Sudan

2Khartoum Dermatology and Venereology Teaching Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan

3Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait

Correspondence to: Mahdi M. A. Shamad, College of Medicine, University of Bahri, Sudan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

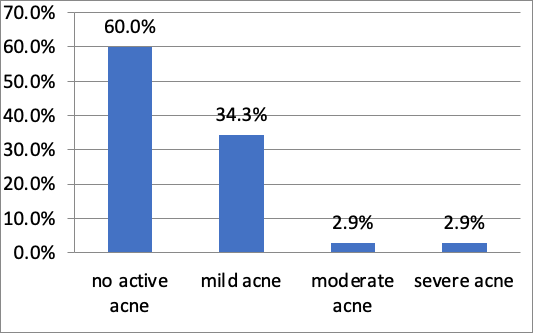

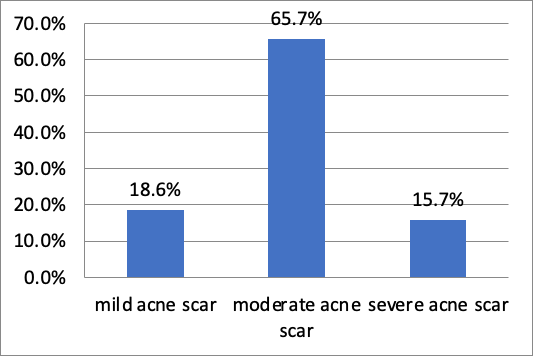

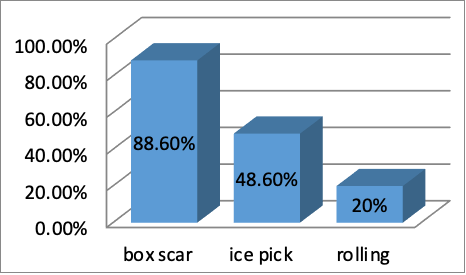

Post-acne scarring is a common and well-known sequelae of acne vulgaris in all Fitzpatrick skin types. It can be classified into three different types: atrophic, hypertrophic or keloidal. Depending on width, depth, and 3-dimensional architecture, atrophic acne scars are further classified into: icepick, boxcar and rolling scars. The objective of this study was to determine the common type of facial acne scar in skin of color. This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted in Khartoum dermatology and venereology hospital, Sudan, in the period of six months from August 2021 to January 2022. A total of 70 adolescents and adult females with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI with facial atrophic post-acne scar were included in this study. Among 70 patients, 60% had no active acne, 34.3% had mild active acne, 2.9% had moderate active acne, and other 2.9% had severe active acne. Regarding severity of acne scars, 65.7% had moderate acne scar, 18.6% had mild acne scar, 15.7% had severe acne scar. The study reported that the most common type of acne scar in skin of color patients is boxcar (88.6%), followed by ice pick (48.6%) and rolling scar (20%). In conclusion, acne scar is a health problem affecting adolescents and adults with skin of color. The most common type of facial acne scar in females with skin of color is boxcar scar.

Keywords: Acne scar, Acne types, Acne vulgaris, Skin of color, Dark skin

Cite this paper: Mahdi M. A. Shamad, Neama Motasem Abdelhai, Nawaf AlMutairi, The Common Type of Facial Atrophic Acne Scars in Skin of Color, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2025, pp. 6-9. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20251401.02.

1. Introduction

- Over 90% of teenagers have acne vulgaris, and 12–14% of those cases continue throughout adulthood, with psychological and social implications [1]. The face, back, and chest are the most frequently affected locations, while any part of the body with significant concentrations of pilosebaceous glands may be affected [2]. The world health organization has declared that acne can cause disability or result in residual disability and should therefore be considered a serious illness that affect the productivity of society [3].In people with skin of color, atrophic acne scarring is an usual, stressful, and long-lasting outcome of untreated acne vulgaris. Preventing post-acne scarring and associated harmful psychosocial consequences requires early detection and treatment of acne vulgaris [4]. Atrophic scarring in people with skin of color is prevalent, unpleasant, and long-lasting consequence of untreated acne vulgaris.Because scarring can last a lifetime, it serves as a noticeable and conspicuous reminder of the illness. [5]. Generally, the severity of scarring correlates to acne grade [6]. Genetic factors, disease severity and delay in treatment are the main factors influencing scar formation [7]. Causes of acne scar formation can be broadly categorized as either the result of increased tissue formation or, more commonly, loss or damage of local tissue [8]. Acne scar can be classified into three different types: atrophic, hypertrophic or keloidal [9]. Atrophic post-acne scars are commonly classified using a system that takes into account both clinical and histological characteristics. [10]. Based on their width, depth, and three-dimensional structure, acne scars can be divided into three fundamental categories:(a) Icepick scars are deep, thin (diameter < 2 mm), depressed, and strongly marginated tracks that reach the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue vertically.(b) Boxcar scars are oval to round indentations with vertical borders that are clearly defined. Unlike icepick scars, they do not taper to a point at the base and are wider at the surface. These scars can range in width from 1.5 to 4.0 mm and be either shallow (0.1–0.5 mm) or deep (≥ 0.5 mm). (c) Rolling scars: these are typically larger than 4 to 5 mm in diameter and result from dermal tethering of otherwise rather normal-looking skin. Superficial shadowing and a rolling or undulating appear of the overlying skin are caused by an atypical fibrous anchoring of the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue.Other clinical classification is: hypertrophic scars, keloidal scars, and sinus tracts [8]. Both hypertrophic and keloidal scars result from an abnormal excessive tissue repair: clinically, hypertrophic scars are raised within the limits of primary excision, whereas keloidal scars transgress this boundary and may show prolonged and continuous growth [11]. Sinus tracts may appear as grouped open comedones histologically showing a number of interconnecting keratinized channels [12].Goodman et al. classified severity of acne scars into four grades: grade I corresponds to macular involvement (including erythematous, hyperpigmented, or hypopigmented scars), whereas grades II, III, and IV correspond to mild, moderate, and severe atrophic and hypertrophic lesions, respectively [6].Among people with acne scars, 80–90% have scars associated with a loss of collagen (atrophic scars) compared with a minority who develop hypertrophic scars and keloids (more commonly seen on the chest and shoulders) [13]. Few studies of acne scarring had been conducted [14], researches in acne scarring in skin of color are even more scanty [15].Acne scars impose a considerable burden for patients, and they are presumed to have a negative impact on their social life. Therefore, one of the main objectives of acne treatment is to prevent scarring. There are numerous guidelines on the appropriate treatment of acne, and several methods for morphological classification of scars have been proposed [16]. However, no consensus has been reached with regard to the evaluation and subsequent classification of acne scars. This study aims to determine the common types of facial acne scar in females with skin of color.

2. Material Patients and Methods

- This descriptive, cross-sectional, hospital-based study, conducted in Khartoum dermatology and venereology hospital, Sudan, in the period of six months from August 2021 to January 2022. A total of 70 adolescents and adult females with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI with facial acne scar presented during the conduction of the study and formed the study population. All were subjected to clinical examination of facial lesions and results were recorded in a specially designed spreadsheet. The data were analyzed by Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) 23.0 software with Chi-square test, as appropriate P<0.05 is considering statistically significant (Confidence Interval: CI 95%). Ethical clearance obtained from the relevant bodies, privacy of data collected was considered, and written informed consent was obtained from tall participants.

3. Results

- All 70 patients with acne scar enrolled in this study were Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V or VI. The study revealed that more than half of them (42 patients, 60%) had no active acne, 24 (34.3%), had mild active acne, 2(2.9%) had moderate active acne, and 2 (2.9%) had severe active acne [figure 1].

| Figure 1. Grade of acne vulgaris in study population |

| Figure 2. Type of acne scar regarding severity |

| Figure 3. Type of acne scars |

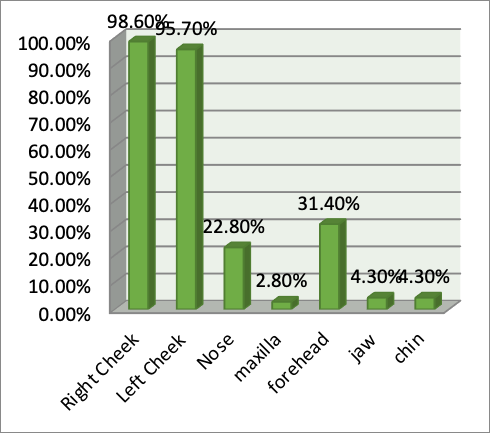

| Figure 4. Sites of acne scars |

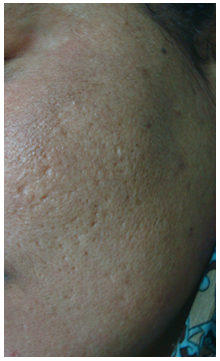

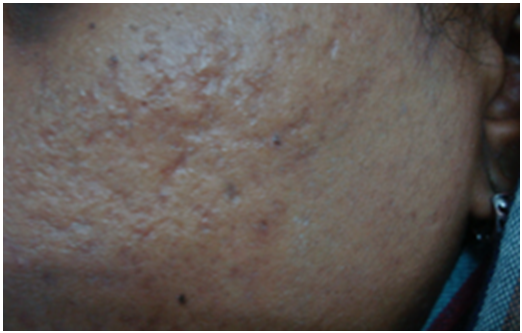

| Photo 1. Post-acne scars |

| Photo 2. Post-acne scars |

| Photo 3. Post-acne scars |

| Photo 4. Post-acne scars |

4. Discussion

- Research on the clinical manifestations of acne vulgaris shows that individuals with skin of color exhibit distinct clinical characteristics from those of other ethnic groups [15]. But post-acne scars were not very well studied in patients with skin of color. The current showed that the most common type of acne scar in female patients with skin of color is boxcar (88.6%), followed by ice pick (48.6%) and rolling scar (20%) this finding is differ from that found in study done in Singapore which revealed that the majority of acne scars were ice pick (97%) followed by rolling scars (82%), and boxcar scars (61%) [4].The study in Singapore also it revealed that (53%) of patients had moderate acne scar, (34%) had mild and (13%) had severe acne scars this is almost similar to this study which showed that the majority of patient had moderate acne scar (65.7%), then mild acne scar (18.6%), then severe acne scar (15.7%) [4].The current study demonstrated that (60%) of patients had no active acne, (34.3%) had mild active acne, (2.9%) had moderate active acne, (2.9%) had severe active acne, this differs from study done in USA which found that (10%) had scars only, (30%) had mild acne, (35%) had moderate acne and (25%) had severe acne [17].

5. Conclusions

- This study showed that post-acne scar is a health problem affecting adolescents and adults with skin of color. Boxcar scars are the most prevalent kind of facial post-acne scar in women with darker skin tone.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML