-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2024; 13(1): 12-21

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20241301.02

Received: Oct. 10, 2024; Accepted: Nov. 12, 2024; Published: Dec. 30, 2024

Vascular and Non-Vascular Adverse Reactions to Face Filler: Systematic Review of Case Reports

Ana Paula Silveira Cruz1, Rachel Rieira1, 2, Samira Yarak1

1Department of Translational Medicine, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

2Centre of Health Technology Assessment, Hospital Sírio-Libanês, São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence to: Ana Paula Silveira Cruz, Department of Translational Medicine, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Facial dermal fillers are among the most commonly performed minimally invasive cosmetic procedures, increasingly popular for their ability to promote skin rejuvenation. However, as the number of procedures rises, so does the potential for adverse reactions to these biomaterials. This study aims to systematically identify and analyze case reports and series of both vascular and non-vascular adverse reactions caused by facial fillers and biostimulators, as well as their treatments. By examining these cases, the research seeks to uncover potential factors that may trigger or amplify certain reactions and to evaluate which treatments are more or less successful in resolving these complications. Using the Cochrane methodology and following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, this systematic review included 378 cases of adverse reactions. Data selection and extraction were performed using the CARE tool. The findings showed a predominance of vascular reactions, particularly those associated with hyaluronic acid, while autologous fat presented the greatest risk for severe outcomes such as visual loss. Non-vascular reactions, especially late-onset cases, were more frequent with non-biodegradable substances. These results highlight the importance of healthcare professionals being well-informed about the potential for moderate to serious adverse reactions, enabling early recognition and management. A thorough understanding of these risks is essential for enhancing prevention strategies and improving treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Facial injections, Fillers, Biostimulators, Adverse reaction

Cite this paper: Ana Paula Silveira Cruz, Rachel Rieira, Samira Yarak, Vascular and Non-Vascular Adverse Reactions to Face Filler: Systematic Review of Case Reports, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2024, pp. 12-21. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20241301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Facial dermal fillers are a cosmetic procedure that is becoming increasingly popular because it promotes skin rejuvenation and an improved appearance with lower costs and shorter recovery times when compared to plastic surgery. [1] Depending on their origin, they are classified as autologous [2], homologous [3], heterologous [4] and synthetic. [5]Synthetic fillers (or biomaterials) are registered with regulatory bodies not as drugs, but as medical devices. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adverse events of medical devices are unexpected problems that can occur during or after their use and may or may not result in permanent disability, injury or death of the patient or user. [6]Despite advances in the chemical and biological characteristics of synthetic fillers, transient and/or persistent adverse reactions can occur, even when procedures are carried out by experienced doctors, and can have a substantial impact on patients' lives. [7]Thus, synthetic fillers can contribute to adverse events due to their complex nature and unique functions or due to errors in use and/or failure to follow care guidelines (intentional or unintentional improper implantation) or inherent patient responses to the biomaterial and biomaterial to the patient (hypersensitivity reactions). [7,8]Most adverse reactions are mild, transient, reversible and not specific to a particular filler. However, serious adverse reactions can occur, leaving patients with long-term or permanent functional and aesthetic deficits. It is notable that there has been an increase in the number and spectrum of adverse events due to the increase in the number of new indications and new treatments. [6] However, the incidence of adverse events has not yet been properly mapped in the literature, which would be an important step towards developing strategies to prevent such adverse reactions.

2. Methods

- This was a systematic review of case reports and series carried out in accordance with the relevant chapters of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [9] and developed in the Translational Medicine Postgraduate Program of the Department of Medicine of the Federal University of São Paulo.The protocol for this systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO review database (CRD42020147555) and the review is being reported in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Harms). [10]

2.1. Study Inclusion Criteria

- The population of interest includes adult individuals of any sex or gender identity, focusing on vascular and non-vascular adverse reactions associated with aesthetic interventions like dermal fillers in the face, performed by any health professional and observed at any time after the procedure. This encompasses reports related to any substance injected into the face, including but not limited to hyaluronic acid (HA), poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), polyprolactone, calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHa), polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), polyacrylamide (PCL), and silicone. The study design consists of case reports or series.

2.2. Outcomes

- Outcomes include the general frequency of adverse events observed, as well as the frequency of these events categorized by substance and injection site. Additionally, the review describes the types of adverse events and classifies reported cases based on their evolution, considering cases resolved when the patient's symptoms were satisfactorily treated. The time interval between the procedure and the onset of symptoms is critical for guiding diagnosis and therapy.However, there is no consensus on the classification by time of onset of adverse reactions to fillers and/or biostimulants. Based on the literature, for the purposes of this review the classification by time of onset was established in three intervals: immediate, early non-immediate and late. This choice was made due to the didactic function of this review, allowing practical reasoning and early conduct by the doctor, and avoiding permanent damage. Thus, each interval was considered as: (i) immediate: up to 24 hours; (ii) early non-immediate: from 24 hours to two weeks; and (iii) late: more than two weeks.

2.3. Search and Selection of Studies

- The following electronic databases were searched: name in full (MEDLINE), Embase and the Cochrane Library on May 28, 2021. An additional search was carried out in the Opengrey gray literature database and annals of congresses in the field. The data selection and extraction process was carried out independently in duplicate to identify potentially relevant studies for inclusion, using the Rayyan platform.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

- The data extracted and identified as homogeneous was aggregated and evaluated using statistical analysis. A descriptive analysis of the results was also carried out. The results of each study are presented individually and in narrative form. Adverse events were counted and related to each of the respective fillers. A standardized data extraction form was used and the quality of the publication of the reports and case series included was assessed using the CARE (Case Report Guidelines) checklist. [11]Electronic and manual searches retrieved 7,577 references. After the study selection process, 256 were included, presenting a total of 378 cases of adverse events associated with facial injection of fillers or biostimulants. Figure 1 shows the study selection flowchart.

| Figure 1. Study selection and inclusion flowchart |

3. Results

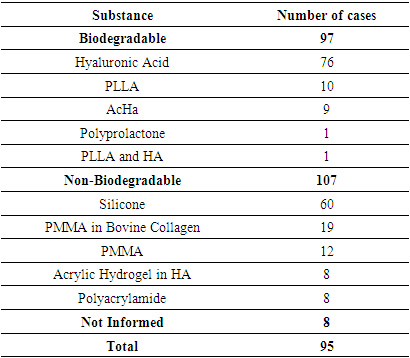

- From the total sample of 378 cases analyzed, the following results were found: (i) 96 cases of vascular adverse reactions (25%); (ii) 270 cases of non-vascular reactions (71%); and (iii) 12 cases in which it was not possible to identify the type of reaction (3%), which were excluded for the purposes of this analysis.Nine reports of abscess formation after filling were found, six of which being late and three early non-immediate cases. All early non-immediate events were associated with the use of HA. Different triggering factors were also identified.

3.1. Vascular Reactions

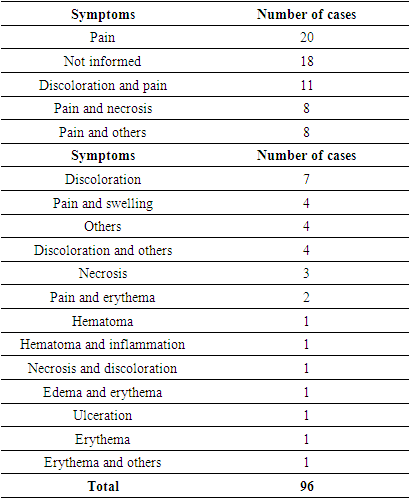

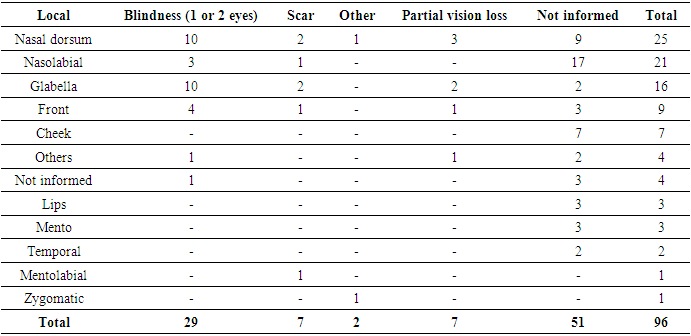

- Ninety-six cases of vascular adverse reactions, including arterial and venous, were identified without distinction, as the differentiation is not mentioned in the majority of the case reports.The main substances causing vascular reactions were HA (67% of cases), CaHA (13%), autologous fat (8%), and PMMA (6.25%). Other substances, such as PLLA, silicone, and PMMA with bovine collagen, were reported in only one patient each.The main symptoms observed in cases of vascular adverse reactions were pain and changes in skin color. All identified symptoms are presented in Table 1 individually, according to the citations in the articles. Sets of signs and symptoms, such as Nicolau Syndrome, were not included as isolated symptoms.

|

|

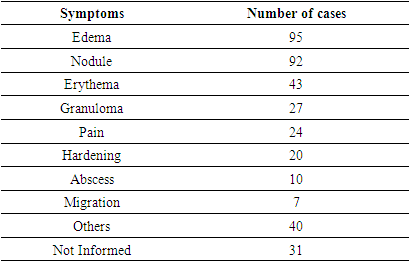

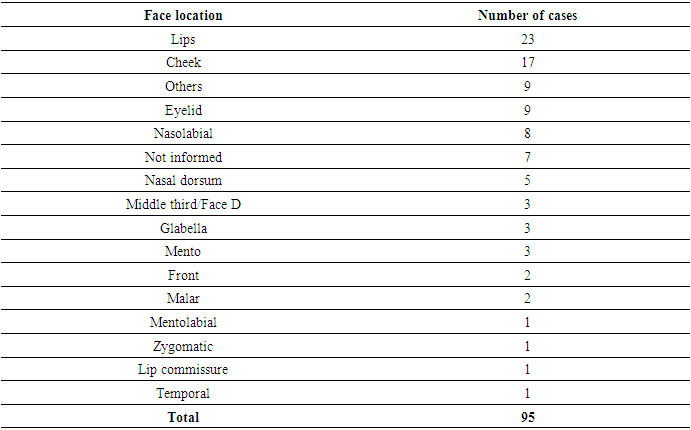

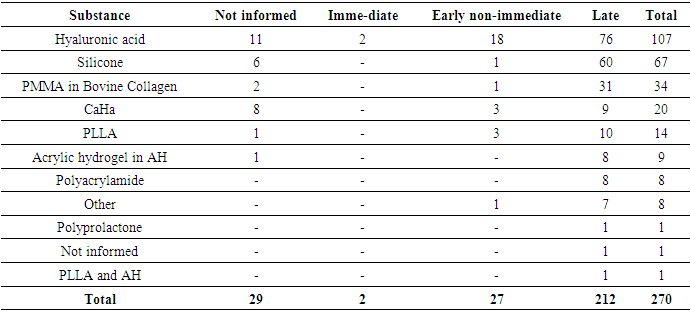

3.2. Non-Vascular Reactions

- This review identified 270 cases of non-vascular adverse reactions related to facial fillers.The most commonly used substance described in cases of non-vascular adverse reactions was HA (107 patients), followed by silicone (67 patients), PMMA (34 patients), CaHA (20 patients), PLLA (14 patients), acrylic hydrogel in HA (9 patients), polyacramide (8 patients), polyprolactone (1 patient), and PLLA combined with HA (1 patient). In nine cases, it was unclear which substance was used.Regarding the symptoms, as shown in Table 3, edema (95 cases) and nodules (92 cases) were the most commonly reported, followed by erythema (43 cases) and granuloma (27 cases). It was noted that the total number of cases in Table 3 exceeds the actual number of cases, as this adverse reaction can cause more than one symptom or clinical sign.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The objective of this review was to identify relationships between factors that could cause or exacerbate specific adverse reactions and to identify practices or treatments that had a higher success rate in resolving cases.Only 52 publications (20.7%) included an introduction with a case summary and scientific basis. Of these, 40 were classified as "partially complete" by the CARE tool, as they provided only a brief case summary without the necessary support. Information regarding interventions performed, adopted protocols, and potential changes was found in only 39 studies, while 80 did not mention any treatment. Concerning patient follow-up and the summary of disease progression, 86 publications provided partial information, and 71 did not present any information.There was also difficulty in identifying complete descriptions of the facial region with adverse reactions, especially in the mid-third. Some authors described the area as the mid-third, while others referred to it as the cheek, malar region, or zygomatic area, complicating analysis and presenting challenges in data description. Regarding the treatment of adverse reactions, most reports involved three or more medications and/or procedures, limiting the ability to identify which was most commonly used.This systematic review identified adverse events described and reported as moderate to severe, according to the WHO classification. [13] Moderate to severe adverse events are considered rare [14], but important due to their impact on both patients and physicians. [15,16] However, according to Haneke (2015), most adverse events are considered mild and easily managed, such as pain, erythema, transient edema, or bruising, which generally resolve within three to five days and are often not reported. [17]A frequent difficulty observed in such cases is that when patients experience an adverse reaction, they often seek another doctor, different from the one who performed the initial procedure, making it challenging to identify the biomaterial and obtain a full case history.The relevance of moderate to severe adverse events is highlighted by the number of publications and the need for a better understanding of this process [18], considering that facial dermal fillers (or biostimulation) are an aesthetic procedure performed on healthy patients seeking to improve their appearance.It is important for physicians to discuss the potential benefits and risks of using fillers with patients before the procedure. An informed and consensual decision brings clarity and enables improvements in terms of technological development and clinical practice.

4.1. Vascular Adverse Reactions

- The regions where vascular adverse reactions with partial or total vision loss occurred, as evidenced in this study, were not different from those reported by other authors [19,20], demonstrating that the nasal dorsum, glabella, forehead, and nasolabial fold are higher-risk areas of the face due to the vascularization involving anastomosis of branches of the external and internal carotid arteries.Occlusion of the external and internal carotid branches by synthetic fillers or autologous fat can result in a series of symptoms, such as skin necrosis, blepharoptosis, strabismus, blurred vision, partial visual loss and blindness. Irreversible total visual loss in these regions of the face arises as a result of this anastomosis, allowing the central retinal artery to be compromised. [19,20]Among the 21 reports of vascular adverse reactions that resulted in visual impairment diagnosed by imaging, fundoscopy or fluorescein angiography were the diagnostic methods used to detect visual loss. Additional tests, such as MR angiography or computed tomography, were used to investigate ischemia or intracranial changes. In only 1 of the 21 cases, color Doppler ultrasound was immediately performed at the procedure site.Although various authors have highlighted the lower risk of visual complications associated with HA [21], the data from this review indicate that HA was responsible for the majority of case reports with visual complications. This review included case reports published over a period of more than 50 years, but due to the lack of information in the reports, it was not possible to compare the incidence of these complications with the total number of procedures performed. Despite the apparent risk, this serves as a warning to professionals regarding HA injections in facial regions, as there was a higher frequency of severe adverse reactions in the forehead, glabella, nasal dorsum, and nasolabial fold areas.Furthermore, the data from this review reveal that not all vascular adverse reactions are immediate. Five cases of adverse reactions were recorded that occurred 72 hours or more after the dermal filler, evolving into skin necrosis: one case from PMMA [22], one from CaHa [23], and three from HA. [14,19,24]None of these five reports showed typical signs of vascular occlusion immediately after the procedure. These cases show that there are not always typical immediate signs of vascular obstruction. Post-procedural discomfort alone may be a symptom of a vascular event and, therefore, should not be ignored. [21]Vascular adverse reactions with immediate onset had a worse prognosis compared to early but non-immediate ones. While 28% of immediate vascular reactions remained unresolved, among early non-immediate reactions, the resolution rate was 100%.Treatment with hyaluronidase resulted in a reduction of impairment in 74% of cases of vascular adverse reactions. Hyaluronidase has the ability to diffuse the product or any material, and it seems likely that the reduction of local edema may contribute to the improvement of blood flow and reflex vasospasm caused by vascular damage. [25]The reports did not mention the recommended dose of hyaluronidase or the ideal timing for starting treatment.Other treatments commonly used were antibiotics, corticosteroids, acetylsalicylic acid, hyperbaric oxygen therapy and peripheral vasodilators - nitroglycerin and heparin. Most of the treatments applied included three or more drugs and/or therapies, which makes it very difficult to identify which might actually have an effect. The small number of cases in which heparin was used as a treatment is noteworthy, since low molecular weight heparin is capable of improving the vascular endothelium and preventing the formation of microthrombi due to vascular damage. [26]The scarcity of in-depth studies on treatments for vascular adverse reactions prevents the development of objective protocols to guide doctors in the search for more effective treatments, with the aim of minimizing complications.

4.2. Non-Vascular Adverse Reactions

- The most important clinical presentation described in the adverse reactions in this review was edema. Most reports of edema were of the late-onset or early non-immediate type, as most immediate edemas are mild adverse events associated with the procedure and disappear within a few hours, thus not typically being the subject of study.The substances that most frequently caused edema were HA and silicone. Only 2 cases of immediate-onset edema were reported, both related to type I hypersensitivity reactions.Late-onset edema was commonly accompanied by erythema (22 cases) and nodules (20 cases). There were no cases of nodules associated with edema, and no other relevant clinical manifestations were found.The second most common clinical presentation was nodules. Non-inflammatory nodules are usually seen immediately after the procedure and result from superficial technique or the injection of large volumes of filler. In this review, no reports of immediate-onset nodules were found.Late-onset nodules, on the other hand, are generally inflammatory, have different etiologies, and are difficult to diagnose, potentially being symptoms and clinical signs of biofilm infection or a foreign body reaction [27]. In this review, the most often observed clinical manifestations associated with late-onset nodules were edema and pain, while in 31 cases, the nodule presented in isolation. Among the early non-immediate onset nodule cases, in the majority (4 out of 6), the nodule was the only symptom, while in one case, it was associated with an abscess and in another, with migration.The biomaterial most commonly associated with late-onset nodules was silicone, followed by PMMA, accounting for more than half of the total late-onset nodule cases. It was observed that non-biodegradable biomaterials, especially silicone and PMMA, present a higher risk of causing late-onset nodules than biodegradable ones.HA has a longevity of approximately six to 18 months [17]; however, this review identified the formation of late-onset nodules up to 12 years after its implantation.The majority of non-vascular reactions, across all clinical manifestations, occurred late. When analyzing each substance in relation to the onset time of reactions, it was noted that only HA, CaHa, and PLLA had a significant number of early non-immediate reactions, with approximately 19%, 25%, and 21% of cases, respectively.In the vast majority of cases, treatment for non-vascular reactions proved effective: 124 cases had complete resolution, and 14 cases showed partial improvement. Only 5 cases, all late-onset, were unsuccessful in treatment:● Late-onset nodule and hardening (1 year) in the lips, caused by PMMA and treated with corticosteroids;● Late-onset edema (16 years) in the lips, caused by silicone and treated with corticosteroids;● Late-onset edema and abscess (6 years) in the malar region, caused by polyacrylamide and treated with incision, drainage, and lifting;● Late-onset edema and nodule (1 year) in the lips and nasolabial region, caused by HA and treated with antibiotics; and● Late-onset edema (3 years) in the cheek, caused by silicone and treated with corticosteroids and antibiotics.Of these cases, only one was caused by a biodegradable substance (HA), and the rest were caused by PMMA, silicone, and polyacrylamide. The higher incidence of severe complications (unresolved after treatment) with non-biodegradable materials is supported by Haneke (2015) [15], who reports that, although no significant difference in the frequency of adverse reactions caused by biodegradable and non-biodegradable substances was noted, those reactions caused by permanent materials tend to be more severe.Additionally, Groen and colleagues (2017) [28] stated that, in general, long-lasting (non-biodegradable) fillers tend to cause more severe and late-onset complications. This is confirmed by the data identified in this review, which reveal a much higher prevalence of late-onset reactions among those caused by non-biodegradable substances (99%), while among reactions caused by biodegradable substances, non-late-onset reactions accounted for 21% of the cases.

5. Conclusions

- Among the vascular adverse reactions, HA was the most common material, followed by CaHa and autologous fat. Although some studies suggest that HA has a lower risk of causing visual complications, this review showed that HA was responsible for the majority of reported cases with these complications, pointing to the need for further studies for more precise conclusions.In non-vascular reactions, late edema was the most frequent sign and symptom, caused mainly by HA and silicone. The second most common clinical manifestation was delayed onset nodules (DONS), with silicone and PMMA being the main causes. These two non-biodegradable biomaterials accounted for more than half of the cases of DONS, as well as presenting a higher risk of serious complications compared to biodegradable materials.As for the treatment of adverse reactions, the lack of data and the absence of standardization prevented clear conclusions. However, hyaluronidase has been shown to be associated with a lower incidence of serious sequelae in vascular reactions. In non-vascular reactions, most cases evolved without sequelae.Although few studies mention it, some triggering factors have included flu-like syndromes (such as Covid) and dental treatments. Of the 256 articles analyzed, only 30 provided sufficient information and 70 presented partial data. Although the lack of data or its partial presentation substantially affected the scientific quality of the data in this review, the number of cases reported was relevant to the descriptive analysis.For a better understanding of adverse events to dermal fillers, it is essential that studies include a complete case history, including the occurrence of previous fillers, triggering factors, treatments and outcomes. Recognizing these adverse reactions makes it possible to establish appropriate treatment early on, enabling more effective action to be taken with the available treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I extend my gratitude to all the mentors who shaped my professional journey, especially Dr. Samira Yarak and Dr. Carolina de O. Cruz Latorraca, for their invaluable guidance. My heartfelt thanks go to my husband, Thiago, for his constant encouragement, and to my daughters, Beatriz and Laura, whose patience and understanding mean the world to me. I also thank my brother Gustavo, family, friends, and patients for their constant encouragement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML