-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2022; 11(1): 7-15

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20221101.02

Received: Aug. 17, 2022; Accepted: Sep. 13, 2022; Published: Sep. 23, 2022

Management of Diabetic Pruritus: An Expert Consensus

Sanjay Kalra1, Asit Mittal2, Sarita Bajaj3, Nitin Kapoor4, Prabhakar M. Sangolli5, Mangesh Tiwaskar6, Ashok Kumar7, Kapil Vyas8, Navneet Agrawal9, Roheet Rathod10, Amey Mane11, Snehal Muchhala12

1Department of Endocrinology, Bharti Hospital, Karnal, India, University Centre for Research and Development, Chandigarh University, Mohali, India

2MBBS, MD (Skin & V.D.), Senior Professor & HOD- R.N.T. Medical College, Udaipur

3Consultant Endocrinologist, Former Director, and Head Dept of Medicine, MLN Medical College, Prayagraj

4Professor of Endocrinology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India, The Non-Communicable Disease Unit, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, 75 Commercial Rd, Melbourne VIC 3004, Australia

5Associate Professor of Dermatology, East Point College of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bengaluru

6Consultant Physician and Diabetologist, Shilpa Medical Research Centre, Mumbai

7Consultant Endocrinologist, CEDAR Clinic, Panipat, Haryana

8Assistant Professor Dermatology, Geetanjali Medical College, Udaipur, Rajasthan

9Consultant Diabetologist, Diabetes, Obesity and Thyroid Centre, Gwalior

10Medical Advisor, Medical Affairs, Dr. Reddy Laboratories, Hyderabad, India

11Cluster Head, Medical Affairs, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Hyderabad, India

12Team Lead, Medical Affairs, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Hyderabad, India

Correspondence to: Roheet Rathod, Medical Advisor, Medical Affairs, Dr. Reddy Laboratories, Hyderabad, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

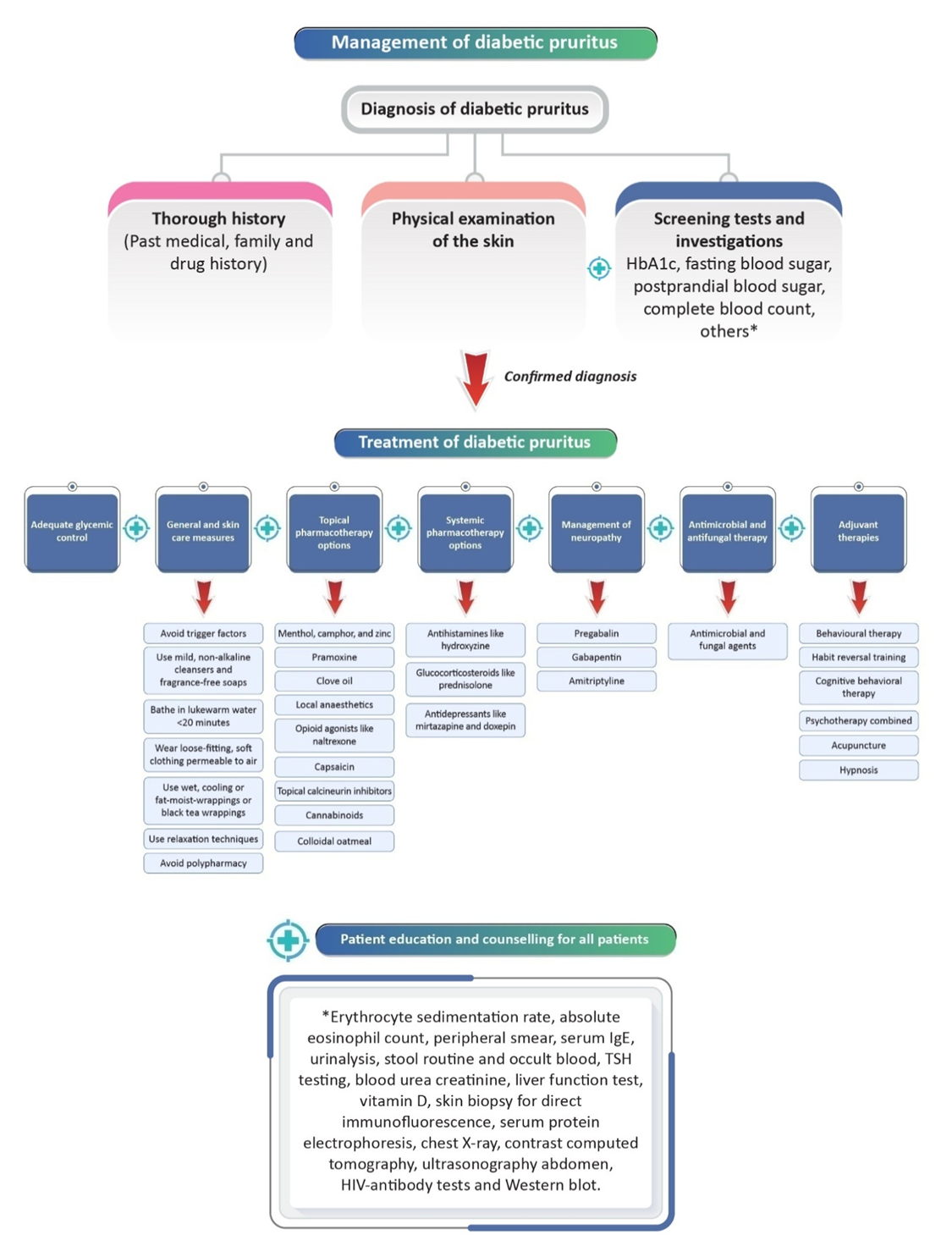

Despite pruritus being a common finding in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), physicians treating diabetic patients may underestimate the frequency of this entity. The current consensus article aims at describing the clinical views of experts regarding various aspects of diabetic pruritus, including prevalence, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. A literature search was performed using databases like PubMed and Google Scholar. Relevant articles were identified using keywords like ‘pruritus,’ ‘diabetes,’ ‘antihistamine,’ and ‘hydroxyzine.’ After screening, 41 relevant articles were identified and included in the document. Pruritus could significantly hamper the quality of life of T2DM patients. Poor management of diabetes is one of the major factors for T2DM patients presenting with pruritus. The two primary pathophysiological aspects associated with Diabetic Pruritus are skin Xerosis and Diabetic Polyneuropathy. Thorough history taking, including family and drug history along with physical examination of the skin, are essential diagnostic perspectives while assessing any patient with pruritus. Furthermore, screening tests and investigations like HbA1c, fasting blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and many more are relevant for appropriate diagnosis of Diabetic Pruritus. Therapeutic approaches include adequate glycaemic control, skin care measures, anti-pruritic topical therapies like pramoxine and systemic therapies like hydroxyzine, optimal management of neuropathy, and adjuvant therapies like acupuncture or hypnosis. The current manuscript aims at providing a collation of evidence-based literature and clinical insights of experts.

Keywords: Pruritus, Diabetes, Antihistamine, Hydroxyzine

Cite this paper: Sanjay Kalra, Asit Mittal, Sarita Bajaj, Nitin Kapoor, Prabhakar M. Sangolli, Mangesh Tiwaskar, Ashok Kumar, Kapil Vyas, Navneet Agrawal, Roheet Rathod, Amey Mane, Snehal Muchhala, Management of Diabetic Pruritus: An Expert Consensus, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2022, pp. 7-15. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20221101.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Diabetes mellitus is known to be associated with various skin manifestations. Skin disorders occur in 79.2% of diabetic patients and cutaneous disease could appear as the first sign of the disease or develop at any time in the disease course. The underlying pathophysiology of diabetes, course of the disease, concomitant comorbidities, and therapies together tend to predispose patients to develop pruritus. [1] Pruritus is described as an unpleasant feeling that leads to a desire to scratch that negatively affects physical and psychological aspects of life. [2]Diabetes can be associated more with localized pruritus compared with generalized pruritus. The scalp, ankles, feet, trunk, or genitalia could be affected. Pruritus is more likely to occur in patients with diabetes who have dry skin or diabetic neuropathy. Involvement of genitalia or intertriginous areas may occur in the setting of infection like candidiasis. [3] Appropriate control of diabetes along with addressing the dermatological and neuropathic components of pruritus are important aspects of management. [4] The current consensus article aims at providing an evidence-based overview and expert opinion on effective diagnosis and management of diabetes-associated pruritus in the Indian context.

2. Current Trends in Diabetes-Associated Pruritus

2.1. Epidemiology

- Despite increasing interest in pruritus, evidence on diabetes-related pruritus is quite limited. Hence, physicians treating patients with diabetes may underestimate the frequency and clinical meaningfulness of this entity. [4] Very few studies have focused on investigating pruritus in diabetes. According to Stefaniak et al., 2019, [1] about 18.4-27.5% patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) suffer from pruritus. [1] Kalra et al., 2022, [5] reported that among patients with diabetes, 38% were suffering from dermatological conditions, and 55% of those patients had pruritus. [5]

2.2. Causes of Pruritus

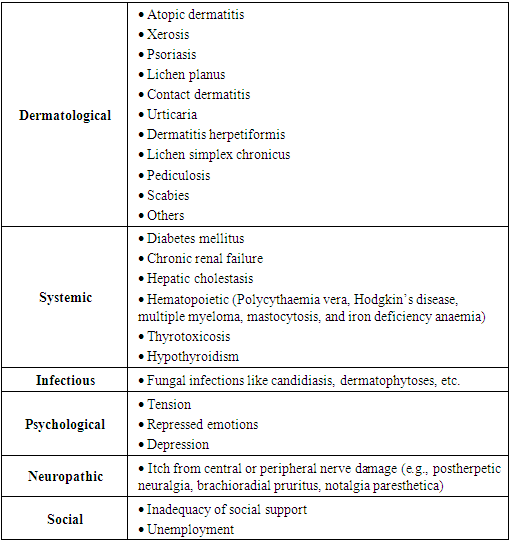

- While approaching a patient with pruritus, one should initially consider a variety of skin disorders like atopic dermatitis or xerosis which are known to cause pruritus. [6] Apart from dermatological causes, pruritus has metabolic, infectious, psychological, neuropathic, and social causes too (Table 1). [6-9]

|

2.3. Impact of Itch-Scratch Cycle

- Occasionally diabetic patients present with generalized Pruritus, and this could complicate chronic nodular prurigo, a lesion characterized by intense pruritic nodular lesions. [10] Severe itching can lead to an itch-scratch cycle, a complex pain-like sensation with a reflex-like response, causing distress and impaired quality of life. [10,11] Scratching could disrupt epidermal barrier and facilitate infection. [11] However, skin ulceration is a rare manifestation. [10]

2.4. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice for Pruritus Management in T2DM

- As per a recent survey, physicians rated their perception of the severity of pruritus as 3.5/5, while patients rated it as 4/5. Physicians perceived poor management of diabetes as a primary cause of pruritus, accompanied by a lack of appropriate hygiene and stress. For patients, pruritus had multifaceted effects on their health, overall well-being, and quality of life. The survey highlighted the need for educating and motivating patients to take counselling for better management of their condition. [5]

2.5. Influence of Psychosomatic Factors on Pruritus

- Evidence suggests a strong negative association between social support and the presence and severity of itch. Anxiety and Depression have been repeatedly associated with chronic pruritic skin diseases. In patients with Psoriasis, intensity of pruritus correlated with a lower quality of life, stigmatization, stress, and depressive symptoms. In patients with Systemic Sclerosis, pruritus showed an association with poor physical functioning and mental health. [9] Furthermore, itch is a common finding in patients with psychiatric diseases. Idiopathic itch affected 36-42% of psychiatric inpatients and was more frequent in those individuals who showed anger-trait, angry temperament, and ruminative catastrophization. [9]

2.6. Consensus Opinion

- The prevalence of pruritus varies in outpatient departments and inpatient departments. Out of every ten diabetic patients, three have severe diabetes, out of which two have localized, and one has generalized pruritus. The occurrence of pruritus is much higher in patients with uncontrolled diabetes versus controlled diabetes. However, it is very difficult to estimate the exact prevalence of diabetic pruritus as it is always multifactorial, and currently, data with respect to Indian settings are inadequate.

3. Impact of Pruritus on Quality of Life

- Pruritus is a relatively frequent symptom in diabetic patients that causes significant impairment to quality of life (QoL). Stefaniak et al., 2021, [4] reported that pruritus subjects had significantly higher scores in both Anxiety and Depression dimensions of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (p < 0.01). [4]Diabetic pruritus is often worse at night, which affects sleep and leads to psychological and mental abnormalities like irritability, Anxiety, and Depression due to unbearable pruritus. Even though pruritus in diabetic patients is not a direct threat to a person’s life, it has a significant impact on QoL as well as on physical and mental health. It also reduces patient compliance with treatment and is detrimental to symptom control. [12]

3.1. Consensus Opinion

- Anxiety and Depression are more common in the diabetic population compared to the general population. This could be a combined manifestation of psychosomatic and neuropathic manifestations. The psychogenic component comes into play in any chronic disease. According to personal experience of experts, diabetic individuals with pruritus will have poor overall satisfaction.

4. Risk Factors for Diabetic Pruritus

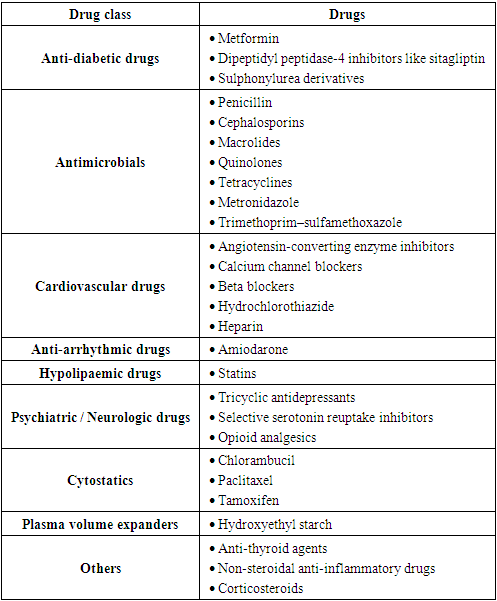

- Patients with diabetes complicated by pruritus generally exhibit pruritus without primary skin damage, or secondary skin damage like scratch marks, crusts, pigmentation, and eczema-like changes after scratching. [12] Stress, diabetes, and environmental factors act as major aetiological factors for pruritus. [13] Figure 1 enlists risk factors related to diabetic pruritus. The higher risk of pruritus in elderly T2DM patients could be linked to factors like atrophy, thinning, dryness, poor repair capacity, and reduced skin barrier function. [12] Due to medical comorbidities, differential pharmacokinetics, polypharmacy, and potential for adverse reactions in elderly patients, it is necessary to be cautious with certain medical therapies for chronic pruritus. [14] Moreover, high serum fasting plasma glucose (FPG), serum creatinine, uric acid, and urea nitrogen levels demonstrate a correlation with higher prevalence of pruritus. [12] Stress and heat have been acknowledged as important factors exacerbating pruritus. [4] In addition to the above factors, several drugs may induce pruritus (Table 2). [15-17]

|

| Figure 1. Risk factors for diabetic pruritus |

4.1. Consensus Opinion

- In addition to the above-mentioned risk factors, additional factors were non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), duration of uncontrolled diabetes, concomitant medications, and obesity. Diabetic pruritus is seen mainly in elderly patients. Polypharmacy and kidney diseases are causes of pruritus in elderly individuals. Pruritus worsens in winter (dry skin) and summer (sweating).

5. Pathophysiology

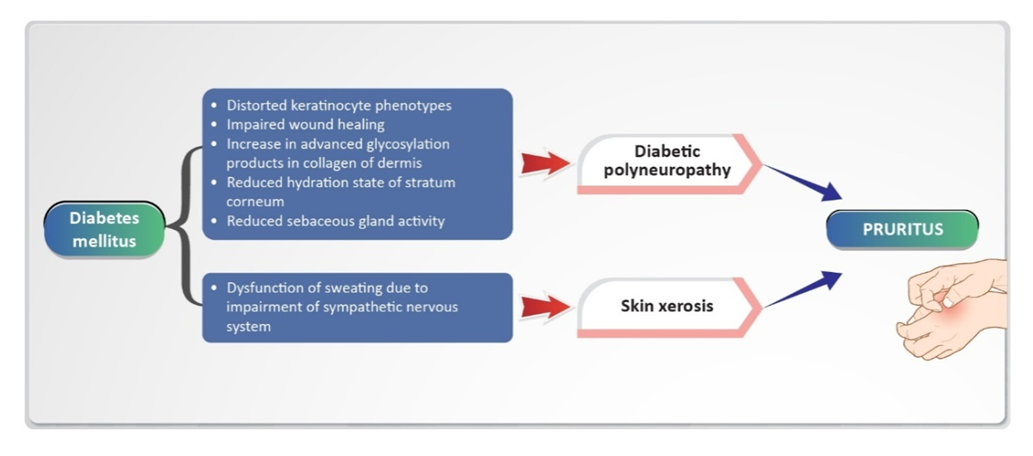

- The main cause of pruritus is poorly controlled long-standing diabetes with altered glucose and insulin levels. Currently, it is believed that two main factors associated with Diabetic Pruritus are skin Xerosis and diabetic Polyneuropathy, thus indicating a dermatological or neurological origin of pruritus. [4] Generalized pruritus might occur in clinically inconspicuous dry skin. [1] The theory of pruritus in T2DM is mainly focused on pruritus because of Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy (DSP) and Small Fiber Predominant neuropathy (SFN). It is also closely related to skin xerosis, as diabetic polyneuropathy is linked to dysfunction of sweating, which is due to impairment of the sympathetic nervous system. As per a recent pathogenetic model of pruritus in diabetes, prolonged hyperglycaemia leads to altered insulin levels which might lead to change in the stratum corneum and subsequent skin xerosis. [4] The pathophysiological aspects of diabetic pruritus have been summarized in Figure 2.

| Figure 2. Factors associated with pathogenesis of pruritus in diabetes |

5.1. Consensus Opinion

- Pathophysiological aspects of Diabetic Pruritus need to be explored further. No studies have investigated how insulin affects small fibers, C-fibers, or A-delta fibers in the skin. The experts opined that insulin injection site reactions are quite common. Insulin analogs such as aspart and glargine are known to cause type-1 hypersensitivity (Pruritus, Urticaria, etc.). Pruritus in diabetes is not just a dermatological condition; it is a multisystemic condition. A multisystemic and comprehensive approach is essential to understand pruritus and diabetes.

6. Diagnostic Essentials for Diabetic Pruritus

6.1. History-Taking and Physical Examination

- A thorough history and physical examination of the skin are imperative while evaluating any patient with pruritus. A complete history which includes past medical, family, and drug history could help in further diagnosing underlying conditions. [7] A thorough inspection of skin including mucous membranes, scalp, hair, nails, and anogenital region is necessary. The distribution of primary and secondary skin lesions must be recorded along with dermal signs of systemic disease. Palpation of the liver, kidneys, spleen, and lymph nodes is a part of general physical examination. [21] The most frequent cause of generalized pruritus is senile Xerosis. Evaluation of dry skin is generally based on visual inspection. However, to determine whether pruritus is caused exclusively by dry skin, ruling out possible causative underlying diseases is essential. [22] Also, if a patient with pruritus experiences polydipsia and polyuria, that could indicate Diabetes Mellitus. [8] In cases of hypersensitivity reactions to insulin analogs in insulin-naïve patients, specific aspects of patient history should be reported. This includes previous insulin exposure, specific insulin analogs used, duration of use prior to the reaction, a clear timeline of the reaction, and precipitating events or confounding factors. [19] The diagnosis of drug-induced pruritus is extremely challenging due to the absence of apparent skin lesions. It could be suspected empirically in patients who are on drugs known to induce pruritus without skin lesions. It is crucial to enquire about current and recent drug intake, including over-the-counter drugs, and dietary and herbal supplements. [23]

6.2. Screening Tests and Investigations

- Important screening tests which form a part of the diagnosis include HbA1c, fasting blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, absolute eosinophil count, peripheral smear, serum IgE, and urinalysis. [7,21] Other tests like stool routine and occult blood, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) testing, blood urea creatinine, liver function test, vitamin D, skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence, serum protein electrophoresis also play an important role. [21] The patient must undergo imaging evaluations such as chest X-ray, contrast computed tomography, and ultrasonography abdomen if the cause is not determined and pruritus persists for a long duration. [22] In cases of suspected human immunodeficiency virus infection, HIV-antibody tests, and Western blot should be performed. [7] In cases of scalp Pruritus, a review of systems for underlying systemic disease is essential for Atopy, Diabetes Mellitus, thyroid diseases, haematologic malignancy, chronic kidney disease, and cholestatic liver diseases. Patients with neuropathic scalp Pruritus often present with abnormal sensations like burning and stinging. [20]

6.3. Consensus Opinion

- Pruritus is a routine part of history-taking in diabetic patients, especially in patients with uncontrolled diabetes along with a history of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. Many physicians do not consider pruritus as a part of history-taking. It would be imperative to exclude all the other dermatological conditions before diabetes is established as the only cause of pruritus. Senile Pruritus of unknown aetiology could be confused with Diabetic Pruritus. One must look for any evidence of Xerosis and peripheral neuropathy as well as metabolic syndrome. In patients presenting with scalp pruritus, pruritus of the back, pruritus of the skin, anogenital Pruritus, candidal Balanoposthitis, Tinea pedis with a lot of cellulitis, type-2 diabetes can be suspected. With respect to drug-induced Pruritus, most patients present with blisters that are easy to diagnose. A good history of vasomotor symptoms is equally important.One must look for excoriation marks, infections (bacterial, candidal, etc.), and Xanthomas (secondary dyslipidaemia). A dermoscopic examination could be helpful as some microvascular changes are not visible to the naked eye at times. If the patient is on long-standing Metformin, a Vitamin B12 test could be done.

7. Management Approaches for Diabetic Pruritus

7.1. Adequate Glycaemic Control

- As fluctuations in glucose levels seem to be one of the reasons for dry skin in diabetes, management of diabetic Pruritus includes normalizing glucose levels accompanied by other measures. [1] Better control of glucose levels might be considered instrumental. [5]

7.2. General and Skin Care Measures

- The management of diabetic Pruritus includes preventive measures like avoiding factors that foster skin dryness. [1] These include dry climate, heat, ice packs, frequent washing/bathing, contact irritants, such as cleansing agents, pet dander, and synthetic fabrics. [1,6] Mild, non-alkaline cleansers must be used, and one must take a bath in lukewarm water for less than 20 minutes. [1] Using skin cleansing agents with a pH of about 5.5 may be of relevance in prevention and treatment of skin diseases. [24]It is advised to wear loose-fitting, soft clothing permeable to air. Wet, cooling or fat-moist-wrappings, black tea wrappings or relaxation techniques could also benefit patients. [1] These measures could help patients reduce Xerosis and thus reduce the itch-scratch cycle. [6] Although some non-pharmacological interventions may be used as monotherapy, they are generally best used in combination with more conventional pharmacologic antipruritic therapies. [25]

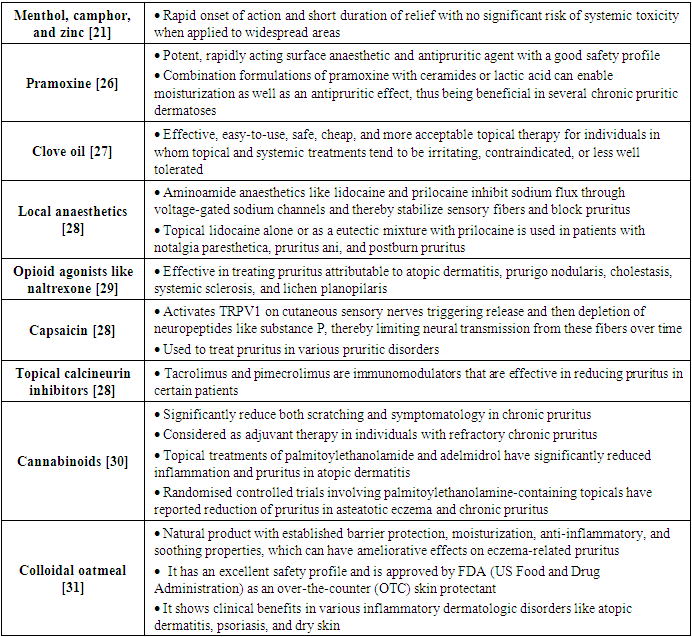

7.3. Topical Pharmacotherapies

- Skin care with emollients like urea-containing moisturizers, amended by topical antipruritics like polidocanol, camphor, menthol, or tannin preparations, is an essential part of diabetic Pruritus management. [1] Topical therapies for chronic pruritus are described in Table 3.

|

7.4. Systemic Pharmacotherapies

- Antihistamines: Systemic antihistamines are the most used drugs for relieving symptoms of chronic pruritus due to dermatological and non-dermatological causes. First-generation antihistamines like Hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, and Promethazine bind to H1 receptors and Muscarinic, Alpha-adrenergic, Dopamine, and Serotonin receptors, which results in a central sedative effect. Hence, they are most useful at night for reducing pruritus and the itch-scratch cycle. [32] Among the sedative first-generation antihistamines, hydroxyzine is considered to be the most potent antihistamine in managing chronic pruritus. [21] Hydroxyzine is characterized by sedative, anxiolytic, and antipruritic activities. [33] A real-world observational study reports good efficacy and tolerability of hydroxyzine, including achieving the desired patient-reported outcomes. [34] In total, hydroxyzine exhibits peripheral antihistamine and central sedative effects. [35].Corticosteroids: They have no direct antipruritic actions but have been effective in patients with inflammatory dermatoses by reducing pruritus and controlling these diseases due to anti-inflammatory effects. Prednisolone is the most frequently used systemic corticosteroid and should not be used longer than 2 weeks due to potential side effects. [32] However, corticosteroids must be cautiously used in patients with T2DM as they may cause hyperglycaemia. [1]Antidepressants: Drugs like Mirtazapine and particularly Doxepin have been effective in pruritus. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) Paroxetine (20 mg/day) has exhibited antipruritic effects in pruritus. [33]

7.5. Optimal Management of Neuropathy

- Painful symptoms of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (DPN) that disturb sleep or activities of daily living could be treated with Pregabalin, Gabapentin, or anti-depressants. [36] Also, Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant widely used to treat chronic neuropathic pain and is recommended as a first line treatment in many guidelines. [37]

7.6. Antimicrobial and Antifungal Therapy

- Oral Ketotifen and topical antibiotic therapy could be helpful in management of pruritus in Prurigo nodularis patients. [38] For various cutaneous infections associated with diabetes like Candidiasis, Dermatophytosis, and bacterial infections, which are likely to be accompanied by pain and pruritus, antifungal agents like Clotrimazole, Nystatin, Fluconazole, Itraconazole, and Ketoconazole are an essential component of therapy. [39]

7.7. Adjuvant Therapies

- To avoid scratching, behavioural therapy like habit reversal could be considered. [7] According to previous reviews, habit reversal training, arousal reduction, and cognitive behavioural therapy have positive effects on psychological well-being as well as on pruritus in several dermatoses. [41] In patients with pruritus and depression, psychotherapy combined with psychotropic medication could benefit. Acupuncture and hypnosis could also have a role in the management of pruritus. [7] The panel experts have formulated an algorithm for management of diabetic pruritus in Indian clinical settings (Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Management of diabetic pruritus |

7.8. Consensus Opinion

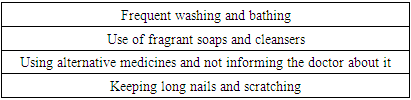

- Along with symptomatic control, psychological and metabolic benefits also get addressed by managing pruritus in diabetic patients. If the physician controls pruritus, the patient’s confidence as well as physician-patient bonding improves. Frequent application of moisturizers with antipruritic properties (at least thrice daily) will control pruritus in the long-term.Using fragrance-free soaps could be beneficial. Topical Cannabinoids, clove oil, and oat complex should be explored more in the Indian settings. Moreover, Lipoic acid 600 mg for 8 weeks and Clopidogrel are two drugs which should be explored further. Tacrolimus could be used for localized pruritus in diabetes for thinner areas of the body. The conventional systemic therapy for pruritus centres on antihistamines. Hydroxyzine, which has additional sedative potential, must be preferred in non-histaminergic pruritus. With regards to neuropathy, Gabapentin and Pregabalin stop neural firing and could be helpful. Drugs like Doxepin are very effective in intractable pruritus (in low doses like 10 mg or 25 mg at bedtime). Pregabalin must be used carefully, as some people are particularly sensitive. A lower dose can be used initially, which can be stepped up slowly (150 mg twice a day, starting with 75 mg at bedtime). Amitriptyline is started with a small dose of 10 mg and is further stepped up slowly. Patient must inform the doctor if he/she is taking alternative medicines. A set of definite ‘don’ts’ for patients with pruritus is given in Table 4.

|

8. Importance of Patient Education and Counselling

- Educating and motivating patients to take counselling is essential for enhancing management of Diabetic Pruritus. Discussion on pruritus during initial counselling could help patients take measures to prevent it. [5] Patients must be advised about measures like keeping their skin hydrated, avoiding hot baths and showers, using only mild soaps, and avoiding contact irritants. This in turn aids in reducing Xerosis and the consequent itch-scratch cycle. [6] Proper monitoring, regular follow-ups with patients, counselling sessions, and identifying mistakes that might lead to recurrence are vital. [5]

8.1. Consensus Opinion

- The patient must be instructed about skin care measures. Patients must be informed about measures that reduce skin dryness, such as taking short showers, using lukewarm water, and keeping nails short. Frequent liberal use of suitable moisturizers needs to be emphasized. Patients must also be instructed not to use any native or alternative medicines that could aggravate pruritus. Patients need to be counselled about aspects like long duration of treatment for the effects to be visible and the necessity of stepping up therapy. Counselling patients regarding the importance of good glycaemic control is also vital. Diabetic patients must be thoroughly counselled about the judicious use of Corticosteroids.

9. Conclusions

- Poor management of Diabetes is one of the primary factors for T2DM patients presenting with Pruritus. A comprehensive patient history, physical examination of the skin, screening tests, and investigations like fasting blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, complete blood count, etc., are important for the appropriate diagnosis of Diabetic Pruritus. Adequate glycaemic control and skin care measures are imperative. Hydroxyzine is a potent antihistamine with sedative potential for managing pruritus. Hydroxyzine is also characterized by anxiolytic benefits that could probably aid in relieving stress due to Diabetes. Optimal management of neuropathy is equally vital. Lastly, educating patients to take counselling is required for better managing their condition. Current data with respect to Diabetic Pruritus is still inadequate, and hence, further robust research is necessary in the future.

Conflict of Interest

- Among co-authors of the current manuscript, three of them are employees of Dr Reddy’s Laboratories.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to acknowledge Scientimed Solutions Pvt. Ltd. for assistance in developing the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML