-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2020; 9(2): 27-31

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20200902.03

An Assessment of Food Allergy and Its Associated Factors in Atopic Dermatitis Patients: A Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh

Md. Khorshed Alam Mondal1, Md. Shafiqul Islam2, Md. Rashedul Kabir3

1Junior Consultant (Skin & VD), 250 Bedded Mohammed Ali Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh

2Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, North Bengal Medical College, Sirajgonj, Bangladesh

3Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Shaheed Ziaur Rahman Medical College, Bogura, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Md. Khorshed Alam Mondal, Junior Consultant (Skin & VD), 250 Bedded Mohammed Ali Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Atopic dermatitis is a genetically predisposed chronic skin disease characterized with cutaneous hyper reactivity to various environmental stimuli, including exposure to food and inhalant allergens, irritants, changes in physical environment (including pollution, humidity, etc), microbial infection and stress. However, very few reports demonstrate the relationship between food allergy in atopic dermatitis patients and other allergic diseases and parameters. So, this study aimed to evaluate if some food allergens has the relationship to the occurrence of other atopic diseases and parameters. Objectives: The aim of the study was to assess food allergy and its associated factors in atopic dermatitis patients. Material & Methods: This was a prospective open label observational study at the Department of Dermatology & Venereology in 250 Bedded Mohammed Ali Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh during the period from January 2017 to December 2018. A total of 112 patients of either sex were included in this study who was suffering from atopic dermatitis. The age of the patients were above 15 were examined. These parameters were examined: food allergy (to wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy), bronchial asthma, and allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis. The statistical evaluation of the relations among individual parameters monitored was performed; it was evaluated, if there is some relation in patients, who suffer from food allergy to the occurrence of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, to the duration of atopic dermatitis lesions (persistent or occasionally), occurrence of positive family history about atopy and the onset of atopic dermatitis. The diagnosis of food allergy was made according to the results of specific IgE (SIgE), skin prick tests (SPT), atopy patch test (APT) and open exposure tests. Results: A total of 112 patients of either sex suffering from atopic dermatitis were included in the study. The age of all the patients was above 15 years. From 112 patients, 66(58.93%) suffer from bronchial asthma and 83(74.11%) patients suffer from allergic rhinitis. Persistent lesions of atopic dermatitis in one last year were recorded in 69(61.61%) patients, only occasionally lesions were recorded in 43(38.39%) patients. Positive findings about atopy in family history were recorded in 63(56.25%) patients, no data about atopy in family history were recorded in 49(43.75%) patients. Food allergy was altogether confirmed in 39 patients (34.82%). The food allergy was confirmed to milk in 01 patients (0.8%) to wheat flour in 03 patients (2.68%), to peanuts in 24 patients (21.43%), to soy in 4 patients (3.57%) and to egg in 07patients (6.25%). Sensitization was altogether confirmed in 73 patients (65.17%). Sensitization to milk was confirmed in 13 patients (11.61%), to wheat flour in 15 patients (13.39%), to peanuts in 18 patients (16.07%), to soy in 26 patients (23.21%) and to egg in 23 patients (20.54%). The sequence of recorded symptoms of food allergy is: oral allergy syndrome in 24 patients (21.42%), pruritus in 15 patients (13.39%), worsening of atopic dermatitis in 15 patients (13.39%), gastrointestinal problems as abdominal pain and cramps in 06patients (5.35%) and anaphylactic reaction after egg and peanuts in 02 patients (1.78%). The results of the occurrence in follow-up categories and their statistical analysis are summarized in (Table 4) where p < 0.014 that means the association was insignificant. Conclusion: The prevalence of bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis is recorded more often in adolescent and adults atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy; these patients also suffer more often from persistent eczematous lesions and have positive data about atopy in their family history.

Keywords: Bronchial asthma, Atopic dermatitis, Food allergy, Persistent eczematous lesions, Allergic rhinitis

Cite this paper: Md. Khorshed Alam Mondal, Md. Shafiqul Islam, Md. Rashedul Kabir, An Assessment of Food Allergy and Its Associated Factors in Atopic Dermatitis Patients: A Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 9 No. 2, 2020, pp. 27-31. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20200902.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Atopic dermatitis is a genetically predisposed chronic skin disease characterized with cutaneous hyper reactivity to various environmental stimuli, including exposure to food and inhalant allergens, irritants, changes in physical environment (including pollution, humidity, etc), microbial infection and stress. The term ‘atopic march’ is used to describe the progression of Atopic disorders from atopic dermatitis in infants to allergic rhinitis and asthma in children. It has been estimated that approximately one-third of patients with atopic dermatitis develop asthma and two-thirds develop allergic rhinitis [1,2]. This concept has been supported by cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [3,4]. The atopic march can occur at any age. Recent evidence suggests that the atopic march does not always follow the classic sequence [5]. Environmental and genetic studies provide evidence that a defect in epithelial barrier integrity may contribute to the onset of Atopic dermatitis and progression of the atopic march. Increase in allergic diseases, including Atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis over the last 30- 40 years has been well documented worldwide [6]. Allergic diseases are also an important public health problem because they significantly increase socioeconomic burden by lowering the quality of life and work productivity of affected patients and their families. However, a few reports demonstrate the co morbidity of food allergy and allergic march in adults. Approximately one-third of children with severe atopic dermatitis were reported to suffer from IgE-mediated food allergy as well. In addition, food allergy that developed at a young age increased the risk for atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis at 8 years of age, in 9-11-year-old children food allergy was highly associated with bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis [7] Two prospective studies show that cow's milk allergy is associated with subsequent development of either bronchial asthma or allergic rhinitis [8]. There is a lack of reports focusing on long-term studies of the clinical and allergometric evaluations observed during the course of atopic dermatitis in respect to its evolution and association with allergic responses in affected patients.

2. Objectives

- To evaluate, if there is some relation in atopic dermatitis patients aged above 15 who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis.

3. Methodology and Materials

- A prospective observational study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology & Venereology in 250 Bedded Mohammed Ali Hospital, Bogura, Bangladesh during the period from January2017 to December 2018. A total of 112 patients of either sex were included in this study who was suffering from atopic dermatitis. The age of the patients were above 15 were examined. These parameters were examined: food allergy (to wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy), bronchial asthma, and allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis. The statistical evaluation of the relations among individual parameters monitored was performed; it was evaluated, if there is some relation in patients, who suffer from food allergy to the occurrence of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, to the duration of atopic dermatitis lesions (persistent or occasionally), occurrence of positive family history about atopy and the onset of atopic dermatitis. The diagnosis of food allergy was made according to the results of specific IgE (SIgE), skin prick tests (SPT), atopy patch test (APT) and open exposure tests. Patients with a positive result in the open exposure test (early and/or late reactions) with the examined food and with a positive result at least in one of the diagnostic methods (sIgE, APT, SPT) to this food were considered as the patients with food allergy. Patients with an early reaction after the ingestion of examined food repeatedly in their history from their childhood were considered as patients with food allergy also; the open exposure test was not performed in these patients because of risk of anaphylactic reaction. Sensitization to examined food was confirmed in patients with the negative results in the open exposure test, but with the positive results in SIgE and/or SPT and/or APT. The evaluation of rhinitis (seasonal or perennial) was made according to the anamnestical data. The evaluation of duration of atopic dermatitis was made as persistent or occasionally according to the dermatologist examination during one last year and according to the patient’s information. The onset of atopic dermatitis was evaluated according to the patient’s history. The family history was evaluated according to the patient’s information (the occurrence of allergy, atopic dermatitis, asthma bronchial, rhinoconjunctivitis in parents, brothers, sisters, and children). The evaluation, if there is some association in patients who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, duration of atopic dermatitis, family history, and onset of atopic dermatitis. Pairs of these categories were entered in contingency tables and the Chi-square test for independence of these variables was performed with the level of significance set to 5%. P-value was calculated using p-value calculator where p < 0.5 considered significant.

4. Results

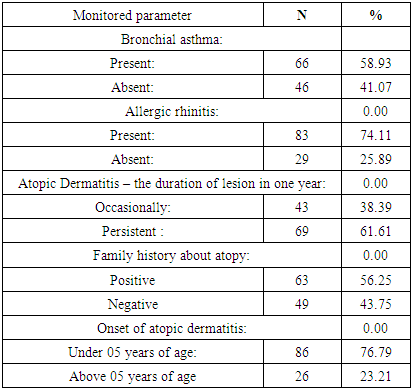

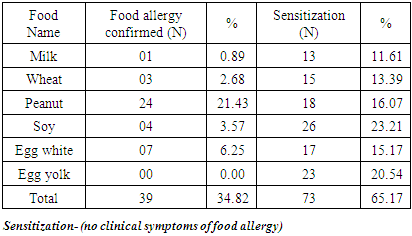

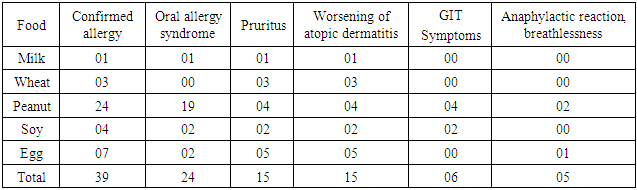

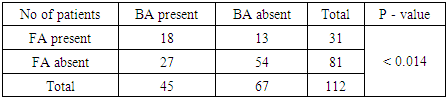

- A total of 112 patients of either sex suffering from atopic dermatitis were included in the study. The age of all the patients was above 15 years. (Table 1) shows the occurrence of the parameters observed in patients with atopic dermatitis-the number of patients suffering from bronchial asthma and from allergic rhinitis, the number of patients with persistent or occasional lesions of atopic dermatitis, the data about atopy in family history, the number of patients with the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age. From 112 patients, 66(58.93%) suffer from bronchial asthma and 83(74.11%) patients suffer from allergic rhinitis. Persistent lesions of atopic dermatitis in one last year were recorded in 69(61.61%) patients, only occasionally lesions were recorded in 43(38.39%) patients. Positive findings about atopy in family history were recorded in 63(56.25%) patients, no data about atopy in family history were recorded in 49(43.75%) patients. The onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age was recorded in 86(76.79%) patients, later onset of atopic dermatitis was recorded in 26(23.21%) patients. The number of patients with food allergy and food sensitization is recorded in (Table 2). Food allergy was altogether confirmed in 39 patients (34.82%). The food allergy was confirmed to milk in 01 patients (0.8%) to wheat flour in 03 patients (2.68%), to peanuts in 24 patients (21.43%), to soy in 4 patients (3.57%) and to egg in 07 patients (6.25%). Sensitization was altogether confirmed in 73 patients (65.17%). Sensitization to milk was confirmed in 13 patients (11.61%), to wheat flour in 15 patients (13.39%), to peanuts in 18 patients (16.07%), to soy in 26 patients (23.21%) and to egg in 23 patients (20.54%). The symptoms of food allergy are recorded in (Table 3). The sequence of recorded symptoms of food allergy is: oral allergy syndrome in 24 patients (21.42%), pruritus in 15 patients (13.39%), worsening of atopic dermatitis in 15 patients (13.39%), gastrointestinal problems as abdominal pain and cramps in 06patients (5.35%) and anaphylactic reaction after egg and peanuts in 02 patients (1.78%). The results of the occurrence in follow-up categories and their statistical analysis are summarized in (Table 4) where p < 0.014 that means the association was insignificant.

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The aim of this study was to evaluate, if there is some relation in atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy to common food allergens (wheat flour, cow milk, egg, peanuts and soy) to other allergic diseases and parameters as bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and duration of atopic dermatitis, family history and onset of atopic dermatitis [10]. Many studies demonstrate the prevalence of allergic diseases; however, most analyzed a limited period from infancy to later childhood and/or to early adolescence [9]. Allergic march refers to a subset of allergic disorders that commonly begin in early childhood, such as food allergies, bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis [11]. Patients diagnosed with a certain allergic disease have a greater likelihood of developing other allergic diseases. The sequence of foods responsible for food allergy at our study with recorded early and/or late allergic reactions is: peanuts in 24 patients (21%), egg in 07 patients (6%), soy in 4 patients (3%), wheat in 03 patients (2.6%) and milk in 2 patients (0.8%). According to our results, patients suffering from atopic dermatitis and allergy to one or more of examined foods suffer significantly more often from bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. Persistent atopic dermatitis lesions and positive data in family history about Atopy are recorded significantly more often in patients with confirmed food allergy to examined foods as well. On the other hand, the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 years of age is not in correlation to allergy to examined foods; the onset of atopic dermatitis under 5 year of age is not recorded significantly more often in patients suffering from allergy to examined food in comparison to patients without allergy to examined foods. Recent modern theories suggest that the most important factor that precipitates allergic march is an impaired epidermal barrier. There is a clear evidence of a relationship between filaggrin gene (FLG) mutations and atopic dermatitis [12]. FLG also increased the risk for bronchial asthma with atopic dermatitis and the risk for allergic allergic rhinitis with/without atopic dermatitis [13]. Moreover, the presence of an FLG mutation in infants with early onset food sensitization and atopic dermatitis increases the risk for bronchial asthma [14]. In adult patients with atopic dermatitis, studies investigating the co-prevalence of atopic dermatitis and food allergy are still scarce and exact data are not available. In sensitized infants to three years of age with atopic dermatitis, food, such as cow milk or hen's egg, can directly cause flares of atopic dermatitis, but 80% of them outgrow their food allergy [15]. According to some studies, early onset of atopic dermatitis was found to be associated with high-risk IgE levels in food sensitization; many epidemiological investigations have suggested that food allergy is a risk factor for the appearance of other allergic disease in later childhood. In another study dealing with atopic March was suggested that atopic dermatitis co-morbid with food allergy in early childhood plays an important role in subsequent development of allergic march. Early childhood is thought to be a key period for the prevention of allergic march, and adolescence is another key period for the prevention of recurrence [16]. The prevention of recurrence would decrease allergic disease in adulthood. Further prospective studies using large cohorts are necessary to assess this issue. Furthermore, Ricci et al, reported that the integrated management of atopic dermatitis decreases the likelihood that affected children would progress toward respiratory allergic disease. Thus, prompt management of atopic dermatitis and food allergy that develop in early infancy may be a successful method for preventing allergic march. According to summary of key findings from 24 systematic reviews of atopic dermatitis about the primary prevention of atopic dermatitis, epidemiological evidence points to the protective effects of early daycare, endotoxin exposure, consumption of unpasteurized milk, and early exposure to dogs, but antibiotic use in early life may increase the risk for atopic dermatitis. With regard to prevention of atopic dermatitis, there is currently no strong evidence of benefit for exclusive breastfeeding, hydrolysed protein formulas, soy formulas, maternal antigen avoidance, omega-3 or omega-6 fatty-acid supplementation, or use of prebiotics or probiotics. Personal and/or family history are evaluated in 130 children, 83 boys and 47 girls, with atopic dermatitis in the age group of 3 months to 1.5 years, with mean age 2.2 + 1.93 years at onset of atopic dermatitis. The data have been compared with those obtained from 130 age and sex matched controls. Both atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma has been known to cause retarded growth. In India, the degree of growth retardation in atopic dermatitis patients has been correlated with extensive eczema, more potent topical corticosteroid use, and more severe coexisting asthma. In a study of 108 children with 'pure atopic dermatitis' (atopic dermatitis without associated bronchial asthma) between 1 and 5 years of age, 54% weighed below 10th percentile while height of 28% were below 10th percentile according to National Center for Health Statistics standards. In India, various epidemiologic factors and clinical patterns of the same were evaluated in 125 patients out of 418 attending the pediatric dermatology clinic over a period of 11/2 years. Of these, 26 were infants (upto 1 year of age) and 99 were children. Mean duration of the disease in the infantile group was 3 months while in the childhood group it was 6 years [17]. In the infantile group, family history of atopy was found in 11 patients (42.3%), while in the childhood group 35 (35.35%) had family history of atopy, 7 (7.07%) had personal history of atopy and 2 (2.02%) had both personal and family history of atopy [18]. The infantile group had more frequent facial involvement and acute type of eczema, while in the childhood type, site involvement was less specific and chronic type of eczema was more frequent. Most of the patients had mild to moderate degree of severity of the disease.LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDYThis study was conducted over a limited period of time. Only the entitled patient’s got opportunity participated in the study. So, the limited sample size, short duration, and a limited study area were the limitations of this study. So, with a large sample, vast area and large span of time, the study may be conducted further.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The prevalence of bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis is recorded more often in adolescent and adults atopic dermatitis patients who suffer from food allergy; these patients also suffer more often from persistent eczematous lesions and have positive data about atopy in their family history.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML