-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2017; 6(2): 25-29

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20170602.02

Prevalence of Lichen Planus in Hepatitis B Patients Attending Ibn Sina Hospital

Sara E. F. E. Ali1, Ahmed N. Aljarbou2, Abdel Rahman M. A. Ramadan3, Khalid O. Alfarouk4, Sali Elhag Ahmed5, Adil H. H. Bashir6

1Khartoum Dermatology Teaching Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan

2Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia

3College of Dentistry, Taibah University, Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah, KSA

4Alfarouk Biomedical Research LLC, Tampa, Florida, USA

5Chinese Friendship Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan

6Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan

Correspondence to: Adil H. H. Bashir, Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

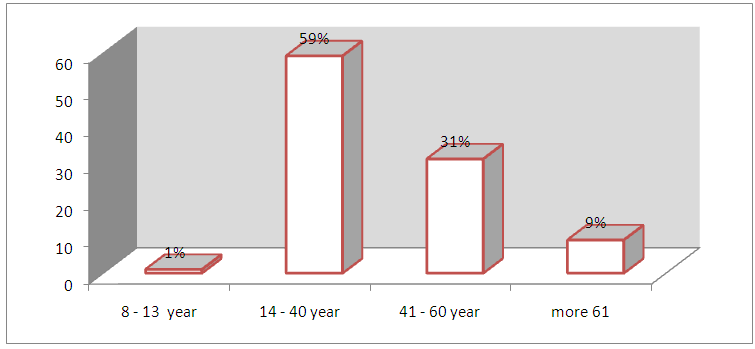

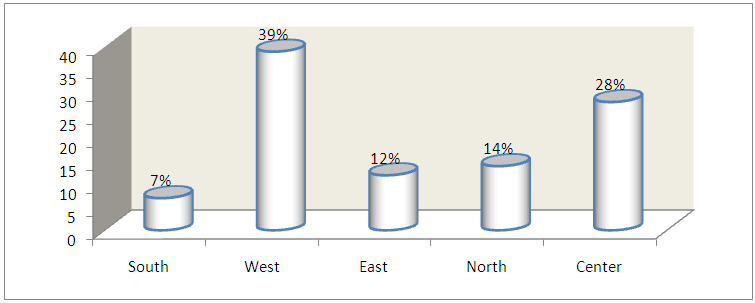

Background: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and chronic liver diseases of varying causes have been studied in literature as possible etiological factors of lichen planus disease (LP). Objectives: Prevalence of LP in HBV Sudanese patients. Methodology: This study was a prospective, observational descriptive hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted at Ibn Sina specialized Gastro-Enterology and endoscopy hospital, during the period from August to October 2015. A total of 100 patients were included in the study, diagnosed with having hepatitis B infection. Questionnaires were filled regarding the patient's demographic and medical data of their disease, and clinical examination of their skin and mucous membranes was done. The data were then analyzed by using SPSS. Result: The results revealed that male represent 64%, and females 36% of the studied population. The age group ( 8-13yr) was represented by 1% of the population, whereas 59% were in the age group (14-40yr), 31% in the age group (41-60yr), and 9% in the age group > 61yr. Seventy patients were married, 27 patients were single, and three patients were divorced. Thirty-nine % resided in the west of Sudan, 28% in the center, 14% in the north, 12% in the east, and 7% in the south. Forty-seven %were infected for years, 44% were infected for months, and 9% for days; 81% had no history of skin diseases, and only 19% had a history of skin diseases. No patient had cutaneous or mucosal LP. Conclusions: This study showed no mucosal or cutaneous LP in hepatitis B Sudanese patients attending IbnSina specialized Gastro-Enterology and endoscopy hospital.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Lichen Planus, Sudan

Cite this paper: Sara E. F. E. Ali, Ahmed N. Aljarbou, Abdel Rahman M. A. Ramadan, Khalid O. Alfarouk, Sali Elhag Ahmed, Adil H. H. Bashir, Prevalence of Lichen Planus in Hepatitis B Patients Attending Ibn Sina Hospital, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2017, pp. 25-29. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20170602.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Lichen planus (LP) usually a self-limited papulosquamous eruption; it is characterized by pruritic violaceous papules commonly affecting the glabrous skin, mucous membrane, nails and hair [1] with characteristic clinical and histopathological features [2]. Etiology of LP is still unknown and is probably multifactorial. Current concepts about the pathogenesis of LP include genetic and immunological factors [3]. Other factors like familial tendency, a disease affecting monozygotic twins, HLA association, anxiety, depression, drugs and carbohydrate intolerance have also been suggested [4].An association of LP with liver disease is now well established [5]. An increased prevalence of LP has been reported in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis and Hepatitis B and C viral infections [6]. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus can be transmitted through blood products, contaminated needles, and during sexual activity. HBV has also been demonstrated in urine, saliva, feces, and nasal secretions on sneezing. About 10% of it Eric patients eventually develop chronic disease. A chronic HBV condition exists when a patient has liver enzyme changes lasting for over six months after infection.Dermatologic disorders associated with HBV infection are serum sickness likeSyndrome, the Recurrent papular eruption of the trunk and upper extremities, Gianotti frost Syndrome, Erythema Nodosum, Urticaria, Lichenplanus, Leukocyte classic vascular, Polyarteritisnodosa, Mixed cryoglobulinemia, Pyoderma gangrenous and Dermatomyositis-like syndrome [7].

2. Rationale

- Ÿ LP can cause emotional and psychological distress and social disability in the affected individuals.Ÿ LP is not uncommon in Sudan and also hepatitis B infection, and there is no study of the correlation between the LP and HBV infection, despite some studies done worldwide with a significant result.Ÿ LP is associated with other diseases, including infection and HBV one of the associated diseases.

3. Objectives

- General: To determine the prevalence of LP in hepatitis B patients attending Ibn Sina Hospital from July to October 2015.Specific:Ÿ To determine the prevalence of LP in hepatitis B patient.Ÿ To detect the most common clinical variants of LP in hepatitis B patients.

4. Patients and Methods

4.1. Study Design

- The study is prospective, observational descriptive hospital-based cross-sectional.

4.2. Study Period

- The study was carried out during the period from August to September 2015.

4.3. Study Area

- The study was conducted at Ibn Sina specialized Gastro-Enterology and endoscopy Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan.

4.4. Study Population

- All study population was known to have hepatitis B infection, who attended the hospital mentioned above during the study period and who met the inclusion criteria.

4.5. Inclusion Criteria

- Patients diagnosed as a case of Hepatitis B, who visit ed Ibn Sina hospital during the study period.

4.6. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-Sudanese patients and who refused to participate in the study.

4.7. Sample Size

- The sample was taken from the total coverage during the study period, i.e. 100 cases.

4.8. Ethical Considerations

- This study was presented and approved by the ethical review committee of Sudan Medical Specialization Board (SMSB), Council of Dermatology and also permission was granted from authorities of health care in the study area, and verbal consent from patients.

4.9. Sampling and Data Collection

- A structured pre-coded questionnaire was used for interviewing patients. Pretesting of the questionnaire was completed to guard against any inconvenience in the questionnaire. The interview and ed after gaining the patient consent. The information obtained in the survey include patients’ age, sex, other demographic factors and clinical examination. The diagnosis made by history and clinical examination and been confirmed by histopathology, whenever the diagnosis is questionable.

4.10. Data Analysis

- The collected data was analyzed by computer using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). The results obtained were presented in tables and figures.

5. Results

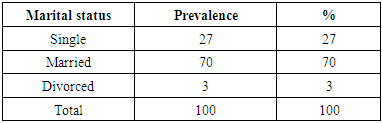

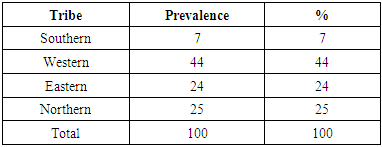

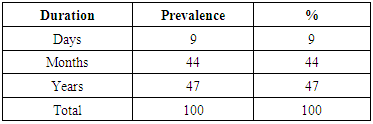

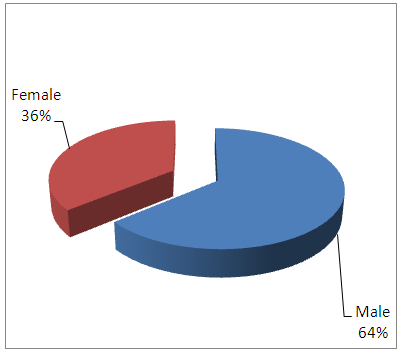

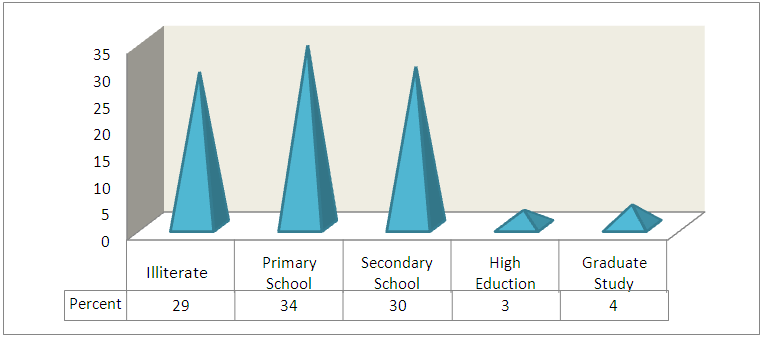

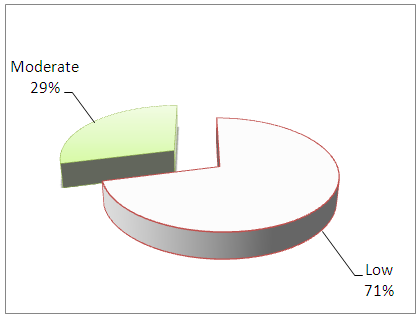

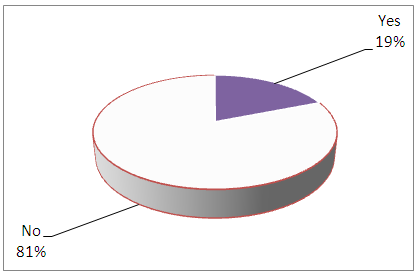

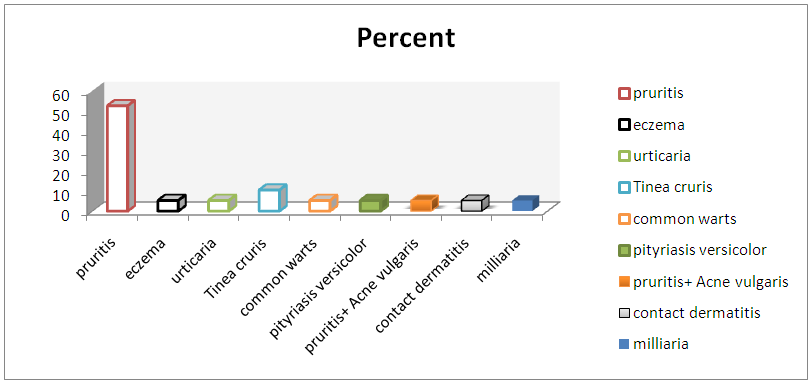

- As mentioned earlier, a total of 100 patients was enrolled in this study; males were 64 patients, and 36 patients were females (Fig. 1). The age distribution of the study population showed one patient in the age group (8-13years), 59 in the 14-40yr age group, 31 in the 41-60yr age group, and nine patients in the > 61yrage group (Fig. 2). The majority of the study population (70%) were married, 27% were singles, and 3% were divorced (Table 1). Table 2 showed regional distribution; as 44% were from the western tribes, 25% from the northern tribes, 24% from the eastern tribes and 7% from the southern tribes. Residence distribution of hepatitis B patients showed 39% resided in the west of the Sudan, 28% in the center, 14% in North, 12% in the east, and 7% in the South (Fig. 3). Education distribution of hepatitis B patients showed 29% were illiterate, 34% were primary school graduates, 30% were secondary school graduates, 3% were highly educated, and (4%) had postgraduate degrees (Fig. 4). The socioeconomic status distribution showed 71% of low socioeconomic status and 29% of average socioeconomic status according to Sudanese standards (Fig. 5). Duration of hepatitis B infection distribution showed 47% were infected for years, 44% were infected for months, and 9% for days (Table 3). Fig. (6) Revealed that 81% of the study sample had no history of skin diseases and only 19% had a history of skin diseases. Fig. (7) demonstrated that no mucosal or cutaneous LP in hepatitis B detected in Sudanese patients attending Ibn Sina hospital, although other skin diseases in the same patients were mentioned as pruritus, eczema and Taenia cruris.

|

|

|

| Figure (1). Gender distribution of Hepatitis B patients in Ibn Sina Hospital: August – October 2015 |

| Figure (2). Age distribution of Hepatitis B patients IbnSina hospital (August –October 2015) |

| Figure (3). Residence distribution of hepatitis B patients in Ibn Sina Hospital (August - October 2015) |

| Figure (4). The education distribution of hepatitis B patients in Ibn Sina Hospital: August - October 2015 |

| Figure (5). The socioeconomic status distribution of Hepatitis B patients in Ibn Sina Hospital: August - October 2015 |

| Figure (6). History of skin diseases Hepatitis B Patients in Ibn Sina Hospital: August - October 2015 |

| Figure (7). Skin disease history and correlation between lichen planus and Hepatitis B Patient in Ibn Sina Hospital Between August –October 2015 |

6. Discussion

- This study showed no one of the 100 hepatitis B patients had mucosal or cutaneous LP, in contrast to the study which was conducted on dermatological manifestation in hepatitis B surface antigen carriers in the east region of Turkey by Dogan et al. (2005) [8]. The Turkish study showed a significant relation between hepatitis B surface antigen carrier and oral LP. The negative association between hepatitis B Sudanese patients and LP in the present study might be related to other environmental, social, and behavioral factors, which guard against the appearance of LP. As the weather in Sudan is dry and hot, this could be considered as unfavorable to virus habitat.The data showed that Hepatitis B is more common in males (64%) than females (36%). This could be justified by males are usually more exposed to infections in their jobs, streets, markets, etc. than women. The females in the Sudan are mostly housewives or have jobs in a cleaner environment than that of males. Therefore, men are exposed to contacts with infected and carriers.The data also exhibited that the western tribes had more prevalence of hepatitis B infection, which represented 44%, and also 39% of hepatitis B infected patients reside in the western Sudan. The high prevalence of hepatitis B infection in the western tribes and the region of the west states might be related to certain social habits and/ or environmental conditions in the tribes and the area. The socioeconomic status seems to have a role since 71% of hepatitis B patients were of low socioeconomic status, and it might be a contributing factor for developing the infection.

7. Conclusions

- It was found no cutaneous or mucosal LP in hepatitis B-infected Sudanese patients examined (100) in this study. Therefore, it can be concluded that there was no association between LP and hepatitis B infected Sudanese patients.

8. Recommendations

- This study is the first survey done in Sudan concerning the possible association between LP and hepatitis B infection. More studies detailed and intensive investigations are needed to clarify the causes in our Sudanese patients. The investigations also must focus on hepatitis B patients with LP to explain this association.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML