-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

p-ISSN: 2332-8479 e-ISSN: 2332-8487

2017; 6(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20170601.01

Successful Treatment of Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis with Intralesional Steroids: Case Report and Literature Review

Eman Karkashan1, Sahar Alsharif2, Azhar Alali3, Maha Dahlan4

1Dermatology Department, King Fahad Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2PGY at the Dermatology Residency Program, Western region, Saudi Arabia

3Dermatology Department, King Fahad Hospital, Almadinah, Saudi Arabia

4Dermatology Department, Security Forces Centre, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Sahar Alsharif, PGY at the Dermatology Residency Program, Western region, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), previously known as histiocytosis X, is a rare disease of unknown etiology, characterized by abnormal and excessive proliferation of Langerhans cells. There is limited data to guide the management of patients presenting with cutaneous LCH. Therefore, the choice of therapy is generally made based upon the site and the extent of involvement with an aim to minimize complications. We report a case of a 35 year old man with Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the skin who was successfully treated with intralesional steroids (triamcinolone acetonide) injection with no recurrence in 52 months follow up.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Histiocytosis X, Triamcinolone acetonide

Cite this paper: Eman Karkashan, Sahar Alsharif, Azhar Alali, Maha Dahlan, Successful Treatment of Cutaneous Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis with Intralesional Steroids: Case Report and Literature Review, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20170601.01.

1. Introduction

- Langerhans cells normally found within the epidermis layer of the skin. They function as antigen-presenting cells in immune system. They can migrate to the local lymph nodes but generally return to the skin. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) refers to a group of idiopathic disorders characterized by reactive accumulation of Langerhans cells in one or multiple organs. Cutaneous langerhans cell histiocytosis is considered a rare disease. Here, we report the case of cutaneous langerhans cell histiocytosis who was successfully treated with intralesional steroids.

2. Case Report

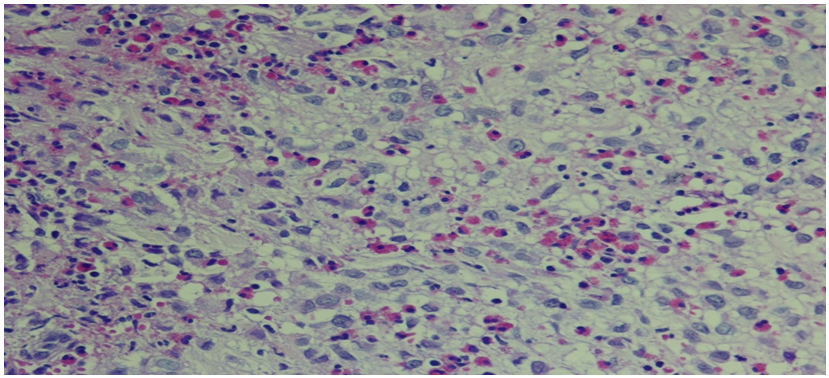

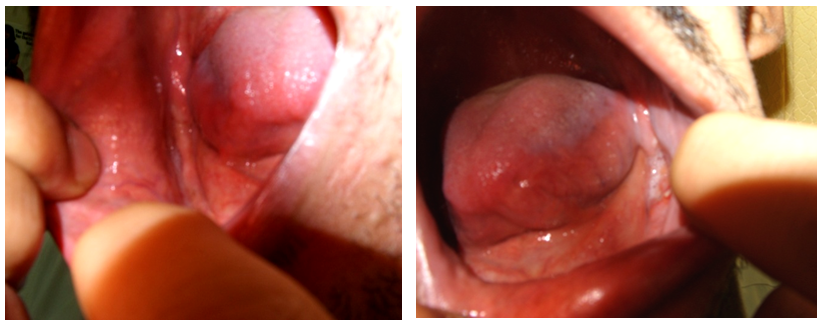

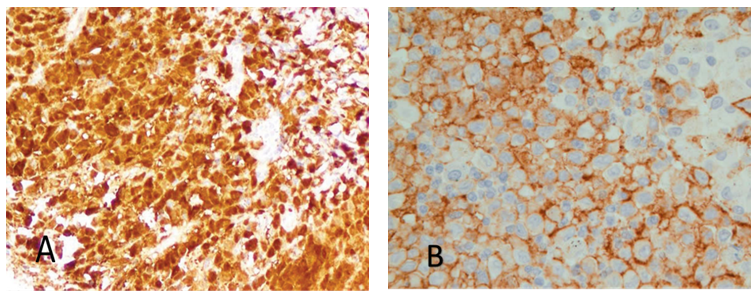

- 35 year old man presented to our dermatology clinic with a 6 months history of painful skin lesion at the perianal area that was gradually increasing in size. He had no similar skin lesions anywhere else in his body. He also denied any recent history of bone pain, or excessive thirst or urination. His past history was remarkable for spontaneous and gradual loss of all his teeth 5 years prior to his presentation following a history of jaw and gingival pain with easy mobility of his teeth. On Examination, his vital signs were within normal range. His head and neck examination was remarkable for the absence of all teeth with normal –appearing buccal mucosa (Figure 1). Otherwise, there was no exophthalmos or any palpable lymph nodes. At the perianal area, there were multiple, well defined, varying in size, ulcerated non scaly erythematous plaques. The largest plaque was 10 x 6 cm in size covered with yellowish erythematous granulation tissue surrounded by a hyper-pigmented rim (Figure 2A). A biopsy from one of the lesions showed focal areas of epidermal ulcerations and the dermis showed atypical histocytic cellular proliferation with large pale folded vesicular kidney shaped nuclei with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 3). The diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis was rendered and confirmed by positive immunostaining for S100 and CD1a markers (Figure 4). Complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all within normal range. Chest X ray and abdominal ultrasound were normal. Bone scan showed some lytic lesions in the jaw bone. The diagnosis of localized Langerhans cell histiocytosis was made and an active disseminated form of the disease was excluded. The skin lesions were treated with monthly intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (20mg/ml) and topical fusidic acid 2% cream for one week and intermittent topical use of betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream. He was referred to maxillofacial clinic where complete dentures were described for him and no bone biopsy or further management plans were recommended. Significant reduction in size of lesions and symptom improvement were noted at his 4 month follow up visit (Figure 2B). The patient did not keep up with follow up visit for 1 year after his 4 month visit, but continued using only MEBO 0.25% W/W cream (herbal formulation possessing b-sitosterol, baicalin, and berberine as active ingredients in a base of beeswax and sesame oil and it promotes wound healing). [1] At that follow up visit total of 16 months since his presentation, he had more than 90% improvement in his skin lesions (Figure 1C). He was then given the 5th intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (20 mg/ml). Although he continued not to be compliant with his regular follow visits, he did not require any further injections and had complete healing at his last follow up appointment which was 52 months from the initial presentation (Figure 1D). During this period, he had no symptoms to suggest development of systemic involvement of the disease and he refused repeat skin biopsy.

| Figure 1. Total loss of teeth with normal appearing mucosa |

| Figure 4. Immunohistochemical markers of the skin lesion. A- LC are positive for S100. B- LC are positive for CD1a |

3. Discussion

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disease of Langerhans cells that express an immunophenotype positive for S100, CD1a and Langerin (CD207), which also contain cytoplasmic Birbeck granules. [2] LCH has been diagnosed in all age groups, but is most common in children from one to three years of age. The incidence appears to be three to five cases per million children, and one to two cases per million adults. [3] The pathogenesis of LCH was unknown. Genetic factors, infectious agents (especially viruses), cellular and immune system dysfunction and BRAF V600E mutation have been considered as possible causes. [4-6] The clinical manifestations of LCH depend on the site or the system involved. In 1987, the Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society grouped the following entities in the LCH spectrum: (1) eosinophilic granuloma (localized lesions, usually in bone), (2) Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (multiple-organ involvement with the classic triad of skull defects, diabetes insipidus, and exophthalmos), (3) Letterer-Siwe disease (visceral lesions involving multiple organs), and (4) congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease) [7] In 1997, experts of the Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society recommended the use of the term Langerhans cell histiocytosis only and the stratification of patients to be based on the extent of disease. [8] The disease is classified by the number of organ systems involved (single or multisystem): Single system LCH: unifocal or multifocal involvement can be found in one of the following organs/systems: bone, skin, lymph node, lungs, central nervous system, or other rare locations (e.g., thyroid, thymus). Multisystem LCH: two or more organs/systems are involved with or without involvement of "risk organs." Risk organs include the hematopoietic system, liver, and/or spleen and denote a worse prognosis. The lung is not considered a "risk organ. [9] In contrast "CNS-risk" areas include the sphenoid, orbital, ethmoid, or temporal bones and denote an increased risk of involvement of the central nervous system. [10] The term "eosinophilic granuloma" is sometimes used to describe the pathology of an individual lesion, particularly isolated lytic processes in bone. It is more important to distinguish the forms with systemic involvement that require systemic management (multisystem LCH) from those with localized lesions and the best prognosis. The first step is to determine the number of organ systems involved. Then patients who have single system involvement should be further subcategorized based upon the number of sites involved (unifocal or multifocal), whereas patients determined to have multiorgan disease should be further subcategorized based upon whether or not organ dysfunction is present. Patients with single system disease are at risk for both local and distant recurrence and at risk for second malignancies, including solid tumors and hematopoietic malignancies. [11] Bone lesions are the most frequent manifestations of LCH (80% of cases), the bones that are most commonly involved by LCH are the skull, femur, mandible, pelvis, and spine. Osteolysis of the maxillary bones leads to floating of the teeth. Cutaneous manifestations are common in LCH and may represent the earliest sign of the disease seen in approximately 40 percent of patients. The most common skin manifestations are brown to purplish papules referred to as congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis and an eczematous rash resembling candida infection. Other skin lesions may be pustular, purpuric, petechial, vesicular, papulo-nodular or ulcerative lesions. [12-14] The most common oral manifestations of LCH are intraoral mass, gingivitis, mucosal ulcers, and loose teeth. [15]Treatment for LCH are chosen on the basis of the age of the patient, the extent and location of disease. In case of cutaneous involvement, management is usually nonaggressive. A subset of patients will have spontaneous regression of cutaneous LCH (i.e., "self-healing cutaneous LCH"). Small retrospective studies and case reports have described a promising response to intralesional corticosteroids injections, [16] oral corticosteroids, [17] topical nitrogen mustard, [18] topical imiquimod, [19] topical tacrolimus, [20] oral methotrexate, [21] oral thalidomide, [22] oral isotretinoin therapy, [23] narrowband UVB, [24] conventional psoralen plus UVA light treatment, [25] interferon alpha, [26] CO2 laser, [27] radiotherapy. [28] This report supports the previously described response to intralesional steroid injection reported by Myers et al in case of limited cutaneous LCH. [16] The underlying mechanism of action of steroids in these cases could be related to the inhibition of cytokines production by LCH cells, [29] or the stimulation of self-healing reaction similar to that described in patients with bone disease. [30, 31] It is necessary to closely follow up these patients because cutaneous involvement could precede the development of systemic form of the disease. Our patient had lytic lesions at jaw bones and complete loss of his teeths which could be explained by involvement of jaw bone by LCH but needs to be proven by bone biopsy which was not agreed on by maxillofacial.

4. Conclusions

- This case supports the use of intralesional steroids in patients with cutaneous form of LCH. This is a very promising method of treatment, and more aggressive interventions like surgery could be avoided.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML