-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

2016; 5(2): 34-37

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20160502.03

The Changing Pattern of Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Sudan: Experience in a Single Center

Lamyaa A. M. EL Hassan 1, 2, Waleed M. ELamin 3, Ameera Adam 4, Khalid O. Alfarouk 4, 5, Anilkumar Mithani 6, Adil H. H. Bashir 4, Ahmed M. Elhassan 2, 4

1School of Medicine, Ahfad University for Women, Omdurman, Sudan

2EL Hassan Histopathology Laboratory, Khartoum, Sudan

3Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Alzaeim Alazhari University, Khartoum, Sudan

4Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum

5Faculty of Pharmacy, AL-Neelain University, Khartoum, Sudan

6Faculty of Medicine, University of Bahri, Khartoum, Sudan

Correspondence to: Adil H. H. Bashir , Institute of Endemic Diseases, University of Khartoum.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The first cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma were described by Moritz Kaposi, a Hungarian dermatologist, in 1872. Ever since many facts about Kaposi’s sarcoma were addressed in the world literature. These included epidemiology, clinical manifestations, etiology, pathology, pathogenesis, and treatment. The tumour has been divided into several subtypes that include the original classic, Endemic (African) Kaposi's sarcoma, Immunosuppression-Associated, Transplantation- Associated Kaposi's Sarcoma and Epidemic or AIDS-Associated, Kaposi's sarcoma. The tumour is caused by the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV). In this communication, we describe our experience with Kaposi’s sarcoma in Sudan. Before the HIV pandemic, the cases were of the classic and endemic African subtypes. After the HIV pandemic, we encountered AIDS-Associated KS and KS in renal transplant patients under immunosuppressive therapy. The classic and African types are still also seen. The clinical manifestations, the pathology, and pathogenesis of KS in Sudan are described and discussed

Keywords: Kaposi’s sarcoma, Sudan, Clinical features, Epidemiology, Pathology

Cite this paper: Lamyaa A. M. EL Hassan , Waleed M. ELamin , Ameera Adam , Khalid O. Alfarouk , Anilkumar Mithani , Adil H. H. Bashir , Ahmed M. Elhassan , The Changing Pattern of Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Sudan: Experience in a Single Center, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2016, pp. 34-37. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20160502.03.

1. Introduction

- The first cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma were described by Moritz Kaposi, a Hungarian dermatologist, in 1872 [1, 2]. Ever since many facts about Kaposi’s sarcoma were addressed in the world literature. These included epidemiology, clinical manifestations, etiology, pathology and treatment [2]. The tumour has been divided into several subtypes that include classic, endemic or African, Immunosuppression-associated, transplantation-associated and Epidemic or AIDS-Associated Kaposi's Sarcoma [1, 2]. In this article, we review Kaposi’s sarcoma in a single center in Khartoum, Sudan. We show the changing features of the disease since it was described for the first time in Sudan in1967 [3].

2. Material and Methods

- All cases seen over the past 40 years in our center were reviewed regarding the epidemiology and clinical manifestations before and after the HIV pandemic.

3. Results

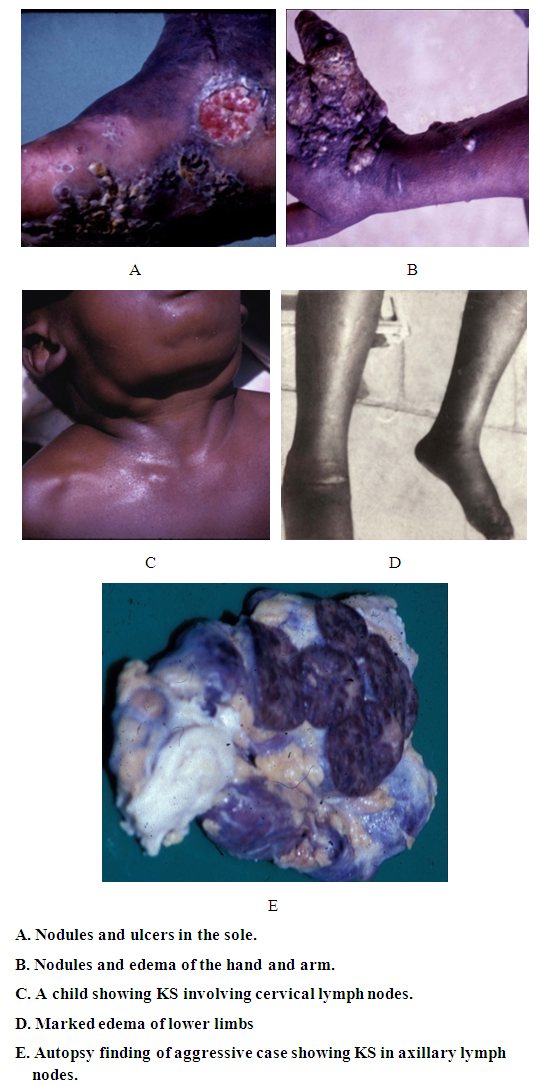

- Kaposi sarcoma before the HIV infectionIn the mid-sixties a total of 11 of biopsy-proven patients with KS were seen in the Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum and the Department of Medicine Khartoum Civil Hospital [3]. All were males in the age range of 32-70 years. Duration was from 1 to 9 years. All presented with skin nodules and sensation of heat in the soles. Their general condition was good. Seventy per cent had non-pitting edema. Seven of the 11 patients were born in or lived for years in parts of Sudan south of Lat 12° north. At the time, this suggested that KS might be due to an infectious agent. Based on this we attempted to transplant K S in outbred mice. The tumour was taken from a patient who died of KS and was transplanted subcutaneously into the mice. It took initially but was later rejected as a xenograft. It is now known that that there is an inbred mouse susceptible for KS. In the late sixties, a patient with KS died six months after the onset of the disease. He had visceral involvement at autopsy. More cases were seen (ten) up to 1980. Some of the cases were over 60 corresponding to original cases of Kaposi we reported before. However, the majority of the ten cases were young individuals (<40) and the tumor was aggressive corresponding to the majority of cases of endemic KS in Africa. In a paper entitled “Superficial cancer in the Sudan in 1974 we reported the frequency of KS in comparison with other skin cancers A study of 1225 primary malignant superficial tumours showed that the most common tumor was squamous cell carcinoma followed by malignant melanoma and basal cell carcinoma 4. KS was the least common. It formed 1.6% and 13.8% of all superficial cancers in the Sudan and South Sudan respectively [4].As mentioned above KS was most common in males. Depending on the subtype of the tumor the duration varied between 1 and 9 years. Lesions were nodules mainly affecting the limbs (Fig 1). The nodules varied in size (Fig 1A, 1B). Edema was often present and sometimes obscured the nodules (1 E). In children KS affected the lymph nodes and there were no nodules in the subcutaneous tissue. However some cases were aggressive and the patients died because of their disease. One patient died 6 months after developing KS. He had extensive nodules in the limbs, involvement of the abdominal and axillary lymph nodes and ulcerations in the small intestine (Figures 1B and C). This patient was seen before the HIV pandemic.

| Figure 1. Clinical features of KS before the HIV Pandemic |

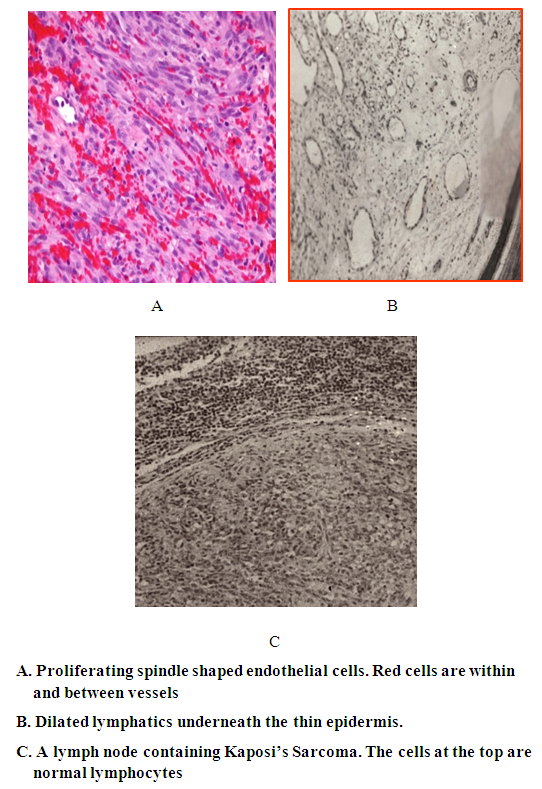

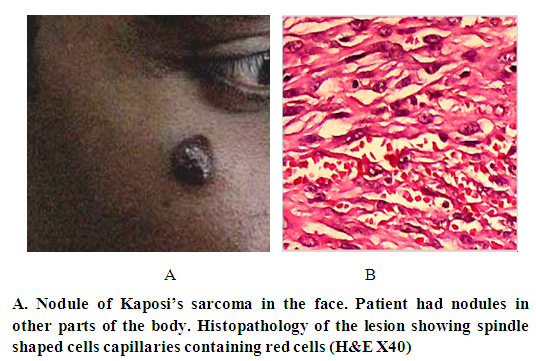

| Figure 2. Pathology of Kaposi's sarcoma |

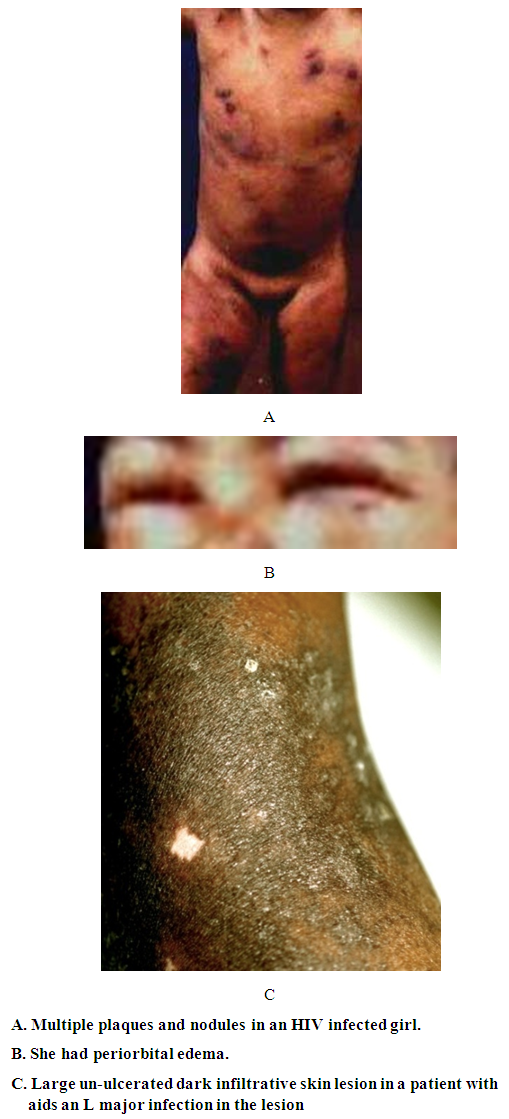

| Figure 3. Kaposi’s sarcoma in two HIV infected patiets |

| Figure 4. Kaposi’s sarcoma in a renal transplant patient |

4. Discussion

- Moritz Kaposi in 1872 was the first to describe a condition subsequently named Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) as a disease in elderly men of Mediterranean or Jewish descent [1]. KS was described in different parts of the world where in most the disease was more common in adult males. In 1981, KS was report in patients infected with HIV/AIDS in homosexual men with AIDS. It was later realized that AIDS associated KS affects females and children and in those with other forms of immunosuppression such particularly renal transplant patients. In the cases presented here we saw all four forms of Kaposi’s sarcoma [6]. Before the HIV the cases fitted into the classic and African forms. In the last few years, we started to see KS in association with AIDS and in renal transplant patients under receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Compelling epidemiologic evidence, including the peculiar geographic distribution of Kaposi's sarcoma, prompted speculation about an infectious cause as well as the possibility of sexual transmission. In 1994, Chang and colleagues identified DNA fragments of a previously unrecognized herpesvirus, which has been called Kaposi's sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV, also known as human herpesvirus) [7], in a Kaposi's sarcoma skin lesion from a patient with AIDS [7–10]. Over 95 percent of Kaposi's sarcoma lesions, regardless of their source or clinical subtype, have been found to be infected with KSHV. The pathogenesis and development of KS lesion has received a lot of attention particularly after the discovery of the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) that causes the disease. KS lesions develop in three stages: the earliest is the patch that changes into a nodule [6]. The patch is a diffuse infiltration of the skin by inflammatory cells that include B and T lymphocytes, macrophages, spindle cells and proliferating blood vessels. We described this early lesion in the two patients with aids. In the child whose color was pale, the lesions were reddish brown. In the adult patient,who had darker skin, the lesion was black. It is interesting that the lesion in this patient was KS and cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. major. After the patch lesion the plaque stage follows [6]. This is more indurated than the patch and is often edematous. The vascularity is marked and there is leakage of red cells from the capillaries into the interstitial tissue and the presence of hemosiderin. Proliferation of spindle cells leads to the nodular stage 5. The spindle cells are believed to be derived from endothelial cells and are regarded as the target for the HPV. We and others have shown that the spindle cells express the endothelial marker CD34.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML