-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

2014; 3(3): 63-67

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20140303.03

The Status of Malignant Melanoma in Iraqi Patients

Khalifa E. Sharquie1, Adil A. Noaim2, Wesal K. Al-Janabi3

1Scientific Council of Dermatology & Venereology-Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations, Department of Dermatology & Venereology, College of Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

2Head of Department of Dermatology & Venereology, College of Medicine; University of Baghdad; Baghdad, Iraq

3Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Medical City

Correspondence to: Khalifa E. Sharquie, Scientific Council of Dermatology & Venereology-Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations, Department of Dermatology & Venereology, College of Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Background: Malignant melanoma is increasing world wide and this observation was also observed in Iraqi population in the last years. Objective: To report the different clinical aspects of malignant melanoma and their varieties in Iraqi patients and to be compared with a previous Iraqi work. Patients and Methods: This case series descriptive study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital; Baghdad, Iraq during the period from January 2007-December 2012. Sixteen patients with malignant melanoma were evaluated. A detailed history was obtained from each patient regarding all sociodemographic aspects related to the disease. Full clinical assessment was also carried out. Incisional or excisional biopsy was performed from each patient according to the size and site of the tumour for histopathological confirmation. All patients had Fitz Patrick skin type of III and IV. Results: The study population consisted of 16 patients (8 females and 8 males) with a male to female ratio: 1:1. Their ages ranged from 12-65 (46.81 ± 16.50) years. The duration of the disease ranged between 0.25-11 (3.28±3.61) years. The following varieties were noticed: 12(75%) cases with acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), 2(12.5%) cases superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) and 2(12.5%) cases nodular melanoma (NM). The duration of acral lentiginous melanoma ranged between 0.25-9 (3.27±3.26) years, superficial spreading melanoma (6 years), while in the nodular type was 0.625 years. Regarding the location and gender of the patients affected, there were 12 (5 males and 7 females) patients on the acral parts of the body [7 on the feet (3males and 4female), 4 on the hands (3 females and 1 male) and 1 male on the leg] and 4 (3 males and 1 female) cases on the back. Conclusions: Malignant melanoma appeared to affect younger age group with equal sexes. Different varieties were observed but mostly acral lentiginous type (75%) and the disease behaved in aggressive way.

Keywords: Malignant melanoma, Worldwide, Iraq

Cite this paper: Khalifa E. Sharquie, Adil A. Noaim, Wesal K. Al-Janabi, The Status of Malignant Melanoma in Iraqi Patients, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2014, pp. 63-67. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20140303.03.

1. Introduction

- Melanoma is a malignant tumour arising from melanocytes [1]. Although malignant melanoma comprises less than 5% of malignant skin tumours; however, it is responsible for almost 60% of lethal skin neoplastia [2]. The incidence (which partially reflects an over diagnosis phenomenon [2] and probably because the pattern of sun exposure) and mortality rates of melanoma have been increasing in recent decades in all parts of the world and this represents a substantial public health problem [3]. Decreased incidence reported from some countries is probably partly due to an influx of low risk immigrants [4-7]. Melanoma is among the most common types of cancer in young adults [8].The mean age of diagnosis is relatively young at 52 years and incidence rises with age [9]. In Australia, age-standardized incidence is continuing to increase despite long-standing prevention campaigns. However, a study has provided evidence for stabilization of incidence rates in those younger than 35 years and the proportionate increase for both insitu and invasive lesions appears to be lower for the most recent period compared with previous periods, providing hope of a reversal in years to come [10]. There has been a steady rise in the incidence of melanoma of the skin in many areas of Australia, New Zealand, North America and Europe since the 1950s [11]. The melanoma incidence rate in Australia is the highest worldwide. Yet, the overall rise was not observed in all age groups [12]. In Europe, there has been a levelling off in incidence in many areas of Western Europe in recent years, but in Eastern and Southern Europe levels are still increasing [13]. Similarly, in the UK in 2001, the melanoma incidence rate (per 100000 populations) was 12.4 (7321 persons)). Despite the increase in incidence in the North of the UK recently, there is some evidence for a levelling off in some areas [14, 15], but not in all [16].US melanoma incidence has increased from 1 per 100 000 to 15 per 100 000 over the last 40 years. This 15-fold increase is more rapid than for any other malignancies [1]. In the United States; women have a slightly higher incidence of melanoma before the age of 40 years. After age 40, men have a higher incidence and the difference becomes remarkably large with increasing age [9], while there is a slight female predominance in Europe [17]. Importantly, in the USA, the SEER programme reported that a trebling of melanoma incidence in males aged 45–64 years over the 30-year period 1969–1999, from 13.5 to 40.0 per 100 000 populationper annum, and a five fold increase in older males aged over 65 years, from 18.8 to 91.9 per 100 000 population per annum. Incidence rates for females aged 45–64 years and for those aged over 65 years have also risen but less steeply than for males, while the incidence of melanoma in younger adults of both sexes aged under 45 years has only risen slightly over a 40-year period [18]. Up to one-fifth of patients develop metastatic disease, which usually is associated with death [1]. So, early detection is an important goal in melanoma management [1]. Deaths from melanoma occur at a younger age than for most other cancers. Mortality rates have increased at a significantly lower rate than incidence. This has been attributed to improved early detection as evidenced by the diagnosis of thinner lesions over this time period [17] mortality seems to be levelling off [16]. In Australia, melanoma mortality seems to have statistically significant decreases in mortality rates for both men and women younger than 55 years have occurred in recent years, for 55–79 year olds, rates are now stable for both men and women whereas previously the rates were increasing. For both men and women 80 years or older, rates have continued an increase of 3–4% per year [19]. Hope for an end to the melanoma epidemic has been seen in the UK, where melanoma mortality fell in young women [14]. In contrast to women, mortality rates are still increasing in men. In the US, it is estimated that nearly every hour an American dies from melanoma [20]. In the USA, mortality appears to be stabilizing in women, but still rising slightly in men [18] as lesions in women tend to be thinner at diagnosis than those in men and female attire may expose more skin overall than male attire [21], it is frequently fatal for dark skinned individuals [22].The four major clinico-pathological types of melanoma are lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), superficial spreading melanoma(SSM), nodular melanoma(NM) and acral lentiginous melanoma(ALM). These variants are not independent risk factors [23] and racial differences of different variants and their locations has been showed [24].LMM is more common in older patient in sunny climates. It appears to be increasing in frequency and some data suggest it is now the most common form of melanoma.SSM used to be the most common form of melanoma and affects adults of all ages with the median age in the fifth decade with no preference for sun damaged skin. The upper back in both sexes and legs in women are the most common sites This contributes to the gender difference in mortality as trunk melanoma has a worse prognosis than leg or thigh melanoma. NM constitutes about 15% of all melanomas. It occurs twice as often in men as in women, primarily on sun exposed areas of the head, neck and trunk. Melanoma occurs most often in light skinned people. The annual incidence rates have been increasing in the order of 3-7% in fair-skinned populations. Melanoma is not commonly encountered in darker races (Africans, South Asians, East Asians and Hispanics [21]), and is less than in individuals of European origin and acral lesions account for a greater share of melanomas in dark skinned individuals with the lowest incidence is found among Asians [23]. ALM is the most common type of malignant melanoma in dark skinned and Asian population (60-72% in blacks versus 24-46% in Asians). This is because the frequency of other types is low in these patients, not because the incidence of ALM is any higher than in white persons [23]. In Asian countries, the disease mostly is ALM affecting young people but unfortunately there are no reports on medical literatures showing the variation in the incidence of the disease at the time being. In Iraq unfortunately there is no actual reported incidence of malignant melanoma, but reports showing not too many cases as there is one report recorded 18 cases within 21 years in one centre in Baghdad [24].On the last few years we have noticed an increase in the number of cases seen in Baghdad centre with different demographic features, this encouraged us to conduct the present study and to record all demographic aspects of this disease during last 6 years.

2. Patients and Methods

- This is a case series descriptive study that was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Baghdad; Iraq during the period from January 2007-December 2012 where Sixteen patients with malignant melanoma were included in this work.A full history was obtained from each patient regarding all sociodemographic aspects including: name, age, gender, address, mobile no., previous medical history, marital status and occupation. The age of onset, duration of disease, evolution of lesion, history of a previous mole or trauma to the site of melanoma, immune suppressive conditions or drugs, family history were also recorded. Full clinical assessment was carried out including: the site, symmetry, border, colour, diameter of lesions. In addition, regional and generalized lymph nodes involvement, liver and other systems were evaluated.Incisional or excisional biopsy was performed for each patient according to the size and site of the tumour for histopathological examination. Baseline haematological and biochemical (including LDH) investigations, chest x-ray, and abdominal ultrasonic study were done. Consultation to the surgeon, physician and oncologist were performed especially for patients who needed sentinel lymph node biopsy. Work up screening for metastasis (abdominal and pelvic CT scan and head MRI) was done. Follow up of all patients was performed. All patients had Fitzpatrick skin type III and IV.Formal consent was taken from each patient after full explanation about the goal and nature of the present study. Also, ethical approval was performed by the Scientific Council of Dermatology and Venereology-Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations.Statistical analysis were done using EPI-info version 6 by estimation of both descriptive and analytic statistics.

3. Results

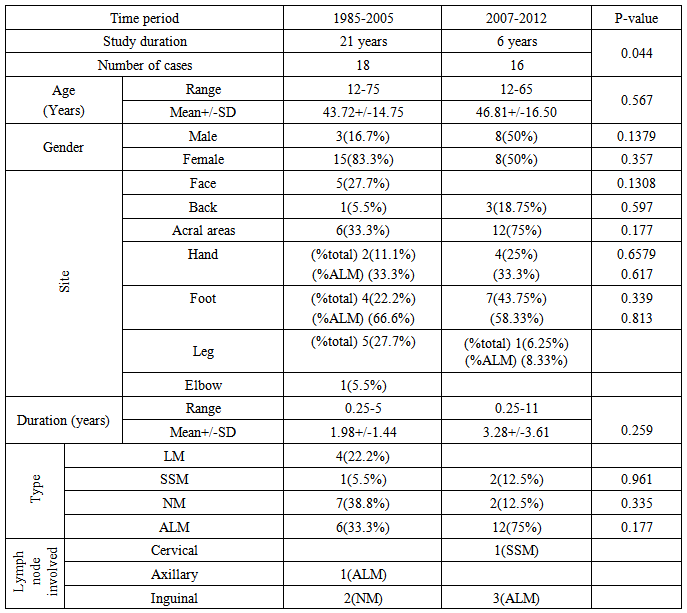

- Table-1; showed the demographic and clinical aspects of all patients. There were 8males and 8 females with male to female ratio 1:1. Their ages ranged from 12-65 years with a mean ± SD of 46.81 ± 16.50 years. The duration of the disease ranged from 0.25-11 years with a mean ± SD of 3.28 ± 3.61 years. The following varieties were noticed: 12(75%) cases with acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), 2(12.5%) cases superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), and 2(12.5%) cases with nodular melanoma (NM). The duration of acral lentiginous melanoma ranged between 0.25-9 years with a mean ± SD of 3.27±3.26 years, superficial spreading melanoma (6 years) while in the nodular type was 0.625 years.

| Table 1. The different demographic and clinical aspects of patients |

| Figure 1. Sixty five years old female patient with ALM and positive hutchison’s sign |

4. Discussion

- In present study 16 cases of malignant melanoma were reported within 6 years while in the previous Iraqi study [24] 18 cases were recorded within 21 year(P-value = 0.044). In the present work there was no sex difference with a male to female ratio of 1:1 while in the previous study [24] (table-2) females were more affected with a ratio of 5:1 but still statistically not significant(P-value = 0.357).

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML