-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology

2014; 3(2): 35-42

doi:10.5923/j.ajdv.20140302.03

A New Diagnostic Approach for Idiopathic Circumscribed Acquired Hypermelanosis; A Clinicopathological Study

Maytham M. Al-Hilo 1, 2, Shakir J. Al-Saedy 1, 2, Ali F. Tahir 2

1Al-Kindy Teaching Center of Dermatology & Venereology, National Scientific Council of Arab Board of Dermatology & Venereology, Iraq

2Department of Dermatology & Venereology, Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

Correspondence to: Ali F. Tahir , Department of Dermatology & Venereology, Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Hypermelanotic skin disorders that involves the hidden area of the body involves a wide range of diseases that includes Mastocytosis, post inflammatory hyperpigmentation, cutaneous amyloidosis, inherited lentigiosis, and the three disorders: Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) and Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP). Twenty-three patients were included in this study. Skin biopsy was performed to all patients at the first visit and repeated one year later for patient in whom the lesions persist. According to the histopathological results, patients were divided into two spectra; lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) spectrum included those who had inflammatory elements and Idiopathic macular pigmentation (IMP) spectrum included those who had no inflammatory reaction in the histopathology. Topical clobetasol propionate ointment prescribed twice daily for patients who revealed inflammatory changes in the histopathology. A Total of 23 patients: 11 male (47.8%) and 12 females (52.1%) with hyperpigmentation in the hidden area of all the body. Their ages varied between 7 to 43 years old with a mean of 24.39±10.2 years. Ten (43.47%) patients were diagnosed after clinic-pathological assessment as lichen planus pigmentosus, while the other 13 (56.5%) patients were founded to have IMP. The age in LPP was between 25 to 43 years with mean of 33.1±8.1, while IMP was between 7 to 32 years with a mean of 18.1±7.5. Patients with unexplainable pigmentations in hidden areas and reveal an inflammatory infiltrate in the biopsy specimens would be diagnosed as LPP. This will eventually include the inflammatory variant of EDP. On the other hand, patients with unexplainable pigmentations in the hidden area with no demonstrable inflammation in the histopathology would be diagnosed as IMP. This will includes the non-inflammatory variant of EDP, Ashy dermatosis, and IEMP.

Keywords: Ashydermatosis, Lichen planus pigmentosus, Idiopathic macular pigmentation, Clinicopathological

Cite this paper: Maytham M. Al-Hilo , Shakir J. Al-Saedy , Ali F. Tahir , A New Diagnostic Approach for Idiopathic Circumscribed Acquired Hypermelanosis; A Clinicopathological Study, American Journal of Dermatology and Venereology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 35-42. doi: 10.5923/j.ajdv.20140302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The hypermelanotic skin disorders were classified into acquired and congenital; the former includes two-sub group circumscribed and diffuse. The acquired circumscribed hypermelanosis involves a wide range of diseases that includes Mastocytosis, post-inflammatoryhyperpigmentation, cutaneous amyloidosis, inherited lentigiosis, and the three disorders: Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) and Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) [1].Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also known as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic hypermelanotic disorder characterized by bluish-grey macules in healthy individuals [2]. Etiology of ashy dermatosis is mostly unknown and it usually affects the face, arms, neck, and trunk. Dark colored individuals are most commonly affected in their second decade of life. Ashy dermatosis usually has a symmetrical distribution but cases with unilateral presentation have also been observed [3]. Mucosal involvement is a rarity [2]. It affect mainly intermediate skin types. There is no clear sexual predilection [4]. Histologic examination of the inflammatory border may demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis with vacuolization of the basal cell layer, occasional colloid bodies, and increased epidermal melanin. The dermal changes are edema of the papillary dermis, a moderate or mild lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, and dermal melanophages. In inactive lesions, there is no vacuolization of the basal cell layer, a diminished dermal infiltrate, and an increased number of dermal melanophages. There is no effective treatment for the disease [3], [4].Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) is a rare skin disorder characterized by asymptomatic, brown- pigmented macules involving the neck, trunk and proximal portions of the extremities. The disease occurs primarily during childhood and adolescence usually without a history of erythema, drug medication or any other skin disorder [5]. The lesions usually appear abruptly and gradually disappear spontaneously over the period of a few months to years without any treatment [6]. The etiology is still unknown. Histopathology shows normal epidermis and many melanophages in the upper dermis [6].Lichen planus pigmentosus characterized by hyperpigmented, dark-brown macules in sun-exposed areas and flexural folds. This entity tends to occur in Latin Americans and other patients with darker-pigmented skin. Histologically, an atrophic epidermis, a vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer with a scarce lymphohistiocytic lichenoid infiltrate, and pigment incontinence are seen. This variant of lichen planus bears significant similarity to ashy dermatosis or erythema dyschromicum perstans and may represent overlap in the phenotypic spectrum of lichenoid inflammation in darkly pigmented skin, with ethnic and genetic factors influencing the expression of disease [9].There are similar histopathologic findings among these diseases. However, distinct clinical, histologic, and immunopathologic differences among these three conditions have been emphasized by some investigators.The present work aims to define a clear approach in the management of patient with hyperpigmentation of the hidden area and re-evaluation of the applicability of the old criteria.

2. Patients and Method

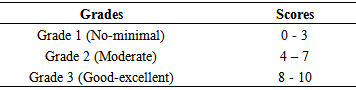

- This is an open labeled descriptive study conducted in Department of Dermatology and Venereology in Al-Kindy Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq in the period from December 2010 to December 2012.The study included any patient who showed acquired circumscribed hypermelanosis of non-scaly pigmented macules and/or patches involving the covered areas (trunk and proximal extremities).The exclusion criteria were any pigmentation that caused by the following conditions: Mastocytosis, drug ingestion, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, macular amyloidosis and vascular disorders.A written consent was obtained from all patients after all details had been explained to the patients. These includes the duration of the study, approval for skin biopsy, application and stoppage of treatment and the follow up intervals. The ethical committee of Al-Kindy teaching center of Dermatology and Venereology approved the study.A full detailed history was obtained including the onset, patient age at the beginning of pigmentation, duration, progression, associated symptoms, family history, residency and a full physical examination including the morphology, distribution, and configuration of rash. Examination of the scalp, nail and mucous membranes was done for all patient as well as determination of skin type.Twenty-three patients were included in this study.Skin biopsy was performed to all patients at the first visit and repeated one year later for patient in whom the lesions persist.According to the histopathological results, patients were divided into two spectra, lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) spectrum included those who had inflammatory elements and Idiopathic macular pigmentation (IMP) spectrum included those who had no inflammatory reaction in the histopathology.Topical clobetasol propionate ointment prescribed twice daily for patients who revealed inflammatory changes in the histopathology.The end of the treatment based on one or more of the following 1. No improvement after two months. 2. Complete resolution.3. No progression of improvement one month forward.Visual analogue score performed by two independents dermatologists with the assessment of improvement depends on the decrease in the pigmentation by giving a score between (0) and (10) and the mean of these scores was taken and graded as the following. Table 1.

|

3. Results

3.1. Age and Gender Distribution

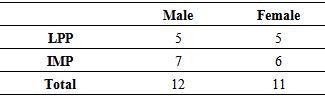

- A Total of 23 patients: 11 male (47.8%) and 12 females (52.1%) with hyperpigmentation in the hidden area of all the body. Their ages varied between 7 to 43 years old with a mean of 24.39±10.2 years. The mean age was 25.09±8.9 years and 23.75±11.5 years for male and female gender respectively. Ten (43.47%) patients were diagnosed after clinic-pathological assessment as lichen planus pigmentosus, while the other 13 (56.5%) patients were founded to have IMP. The age in LPP was between 25 to 43 years with mean of 33.1±8.1, while IMP was between 7 to 32 years with a mean of 18.1±7.5. Table-2

|

3.2. The Onset of Pigmented Lesions

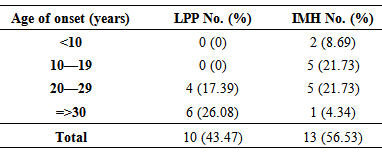

- All patients had shown an insidious onset of pigmentation with slow progression. Neither history of preceding erythema nor associated pruritus was revealed. Table-3

|

3.3. Duration of the Pigmented Lesions

- The duration of illness varied between 3 months and 96 months with a median of 12 months, the duration in LPP group ranged between 2-94 months with a median of 30 months, while the duration for IMP was between 2-48 months with a median of 17 months.

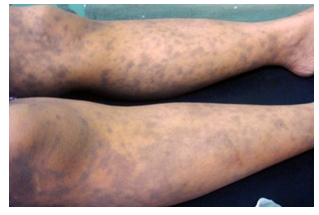

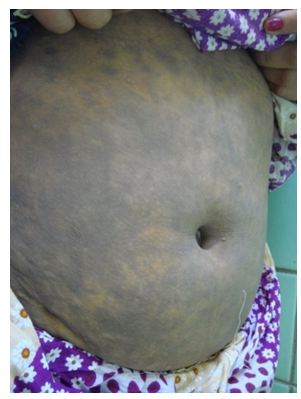

3.4. Color Spectrum of the Hyperpigmented Lesion in LPP and IMP

- Eight patients (80%) with lichen planus pigmentosus had violaceous color and two patients (20%) had bluish hue (Fig. 1 & Fig. 2), while in the IMP nine (39.13%) patients had a slate blue versus four (17.39%) patients had brownish color. (Fig. 3 & Fig. 4)

| Figure 1. Thirty years old male patient with 8 month history of lichen planus pigmentosus |

| Figure 2. Twenty nine years old male with one year history of LPP treated with topical clobetasol ointment |

| Figure 3. Thirty nine years old female with 4 months history of LPP |

| Figure 4. Forty eight years old female with 2 years history of IMP of the arms, thighs and trunk |

3.5. Fitzpatrick Skin Type of Patients with Pigmentation

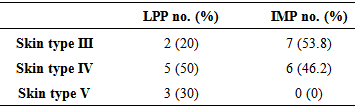

- Patients with LPP had Fitzpatrick skin type III to V, while those with IMP there skin type was between III and IV. Table-4

|

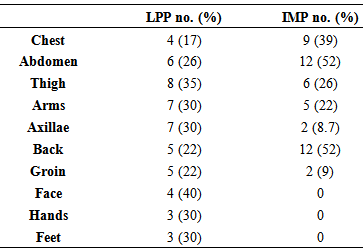

3.6. Site of Skin Lesions in LPP and IMP

- Six of the patients with LPP had involvement of face, hands and/or feet, while none of the patient with IMP had involvement of these sites. Table-5

|

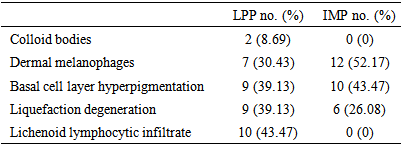

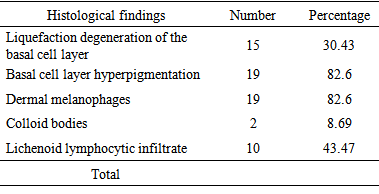

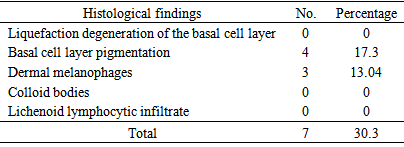

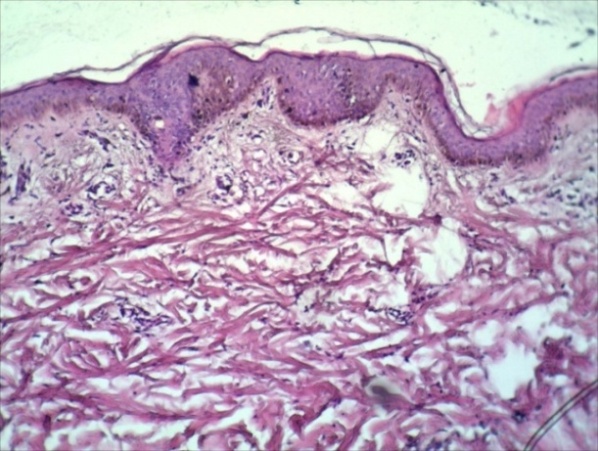

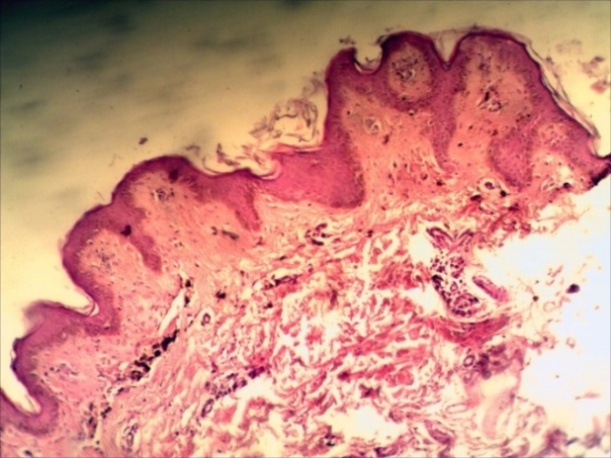

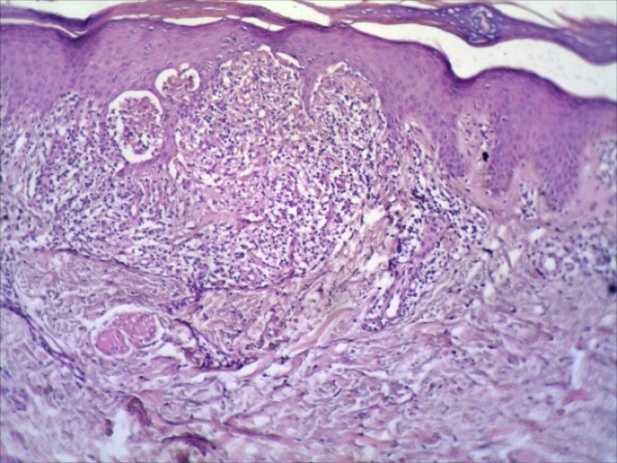

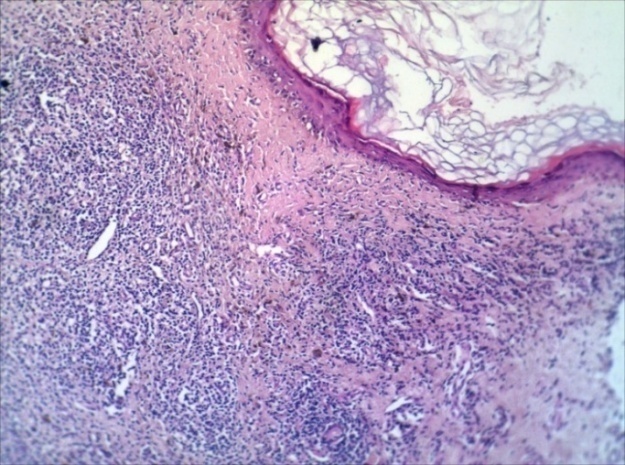

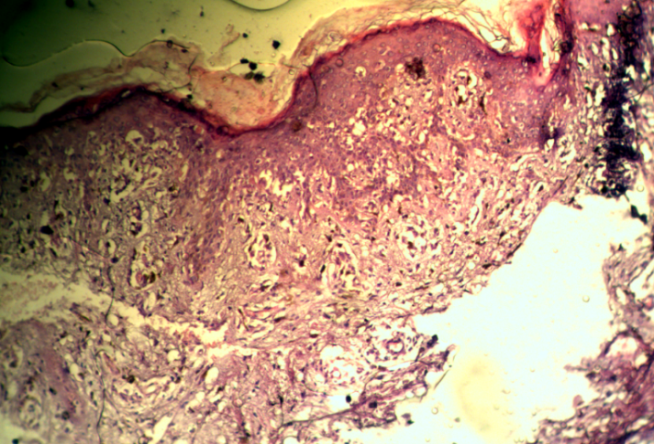

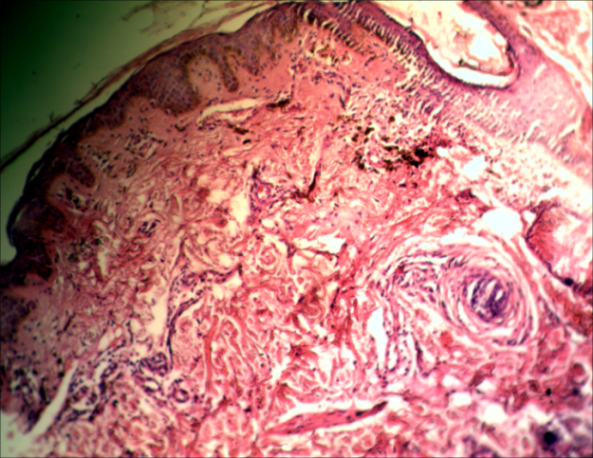

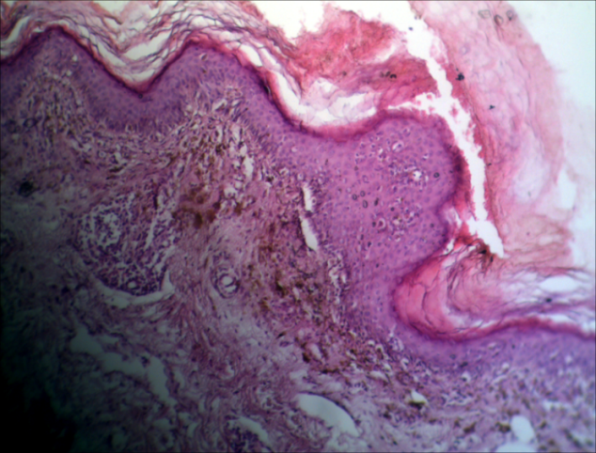

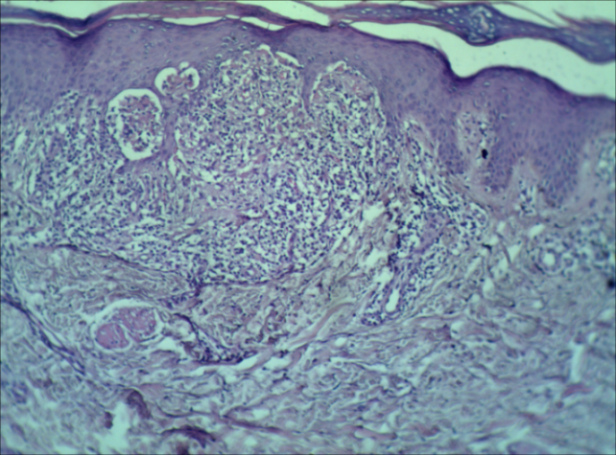

3.7. The Initial Results of Histopathological Examination

- The result of histopathological examination at the initial visit revealed a liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer in 15 (30.43%) patients, basal cell layer hyperpigmentation in 19 (82.6%), dermal melanohages in 19 (82.6%) and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in 7 (30.43%) patients. Figure 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and Table-6.

|

|

| Figure 5. Show Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation & Dermal melanophages |

| Figure 6. Show Dermal melanophages without dermal Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate |

| Figure 7. Figure Show dermal Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with Liquefaction degeneration |

| Figure 8. Figure Show dermal Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with Liquefaction degeneration |

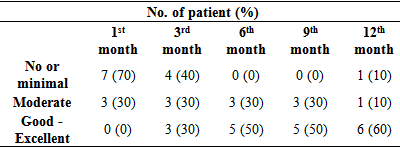

3.8. Response to Treatment

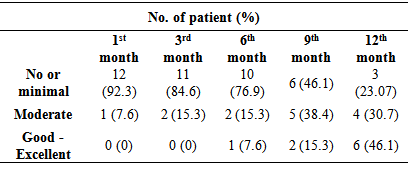

- After treatment with topical potent steroid (Clobetasol Propionate Ointment), all the 10 patients who received treatment, showed a different response. After treatment with topical potent steroid (Clobetasol Propionate Ointment), all the 10 patients who received treatment, showed a different response. After the 12th month, six (60%) patients with LPP gained a good - excellent response and only one (10%) patient had no or minimal. Table-8

|

3.9. Follow up of Patients with IMP (Who were not Received any Treatment) through a 12 Months Duration

- Follow up of patients with IMP (who were not received any treatment) through a 12 months duration shows No or minimal in 3 (23.07%) patients, Moderate 4 (30.7%) patients, and Good – Excellent 6 (46.1%) patients. Table-9

|

3.10. The Results of Histopathological Examination at the End of 12 Months Follow-up

- Twelve months later, second biopsy done for 2 (8.6%) patients with LPP and 3 (13.04%) patients with IMP, those patients how failed to show progress. The histopathological results of all tissue specimens appointed neither liquefied degeneration nor lichenoid infiltrates. Pigmentory incontinence observed in all histopathologically examined slides. Table-10

| Figure 9. Show Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation & Dermal melanophages |

| Figure 10. Show Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation, Dermal melanophages with dermal Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate |

| Figure 11. Show Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation & Dermal melanophages |

| Figure 12. Show dermal Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with Liquefaction degeneration |

|

4. Discussion

- Idiopathic circumscribed hypermelanosis of the hidden areas includes wide range of dermatological diseases with a big dilemma in the supposed criteria of each one of them. Lichen planus pigmentosus, usually present with macular hyperpigmentation involves chiefly the face, neck and upper limbs, although it can be more widespread, and varies from slate grey to brownish black; it is mostly diffuse, but reticular, blotchy and perifollicular forms are seen. The duration at presentation ranged from 2 months to 21 years in one series. 9 The mucous membranes, palms and soles are usually not involved, but involvement of mucous membranes has been observed. (11)Erythema dyschromicum perstans, clinically, the condition is characterized by numerous macules of varying shades of grey with a red, slightly raised and palpably infiltrated margin. They vary in size and tend to coalesce over extensive areas of the trunk, limbs and face. Against the general greyish background are macules of hypomelanosis or hypermelanosis. The condition is persistent and slowly extends, but causes no symptoms.11 A proposed clinical classification has been devised, dividing ashy dermatoses from erythema dyschromicum perstans with the former lacking erythematous borders, and having a third category for simulators such as lichen planus variants, and medication-induced melanodermas. (13)Idiopathic eruptive macular hyperpigmentation is an uncommon disorder of pigmentation characterized by an eruption of asymptomatic, brown macules 5 mm to several cm in diameter involving the trunk, neck, and proximal extremities in children and adolescents. There is no previous drug exposure and the lesions disappear gradually over several months to years. Histopathologically, there is hyperpigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages. (14)There is a lack of consensus as to whether idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a variant of EDP seen more commonly in children or a distinct entity. (7) De Galdeano et al. have studied five cases of IEMP. (8) They concluded that the condition appears to be a distinct clinical and histopathologic entity, and summarized some basic diagnostic criteria necessary to recognize this rare disease: (1) Eruption of brownish asymptomatic macules involving the trunk, neck, and proximal extremities in children or adolescents; (2) Absence of a preceding inflammatory process; (3) No previous drug exposure; (4) Basal cell layer hyperpigmentation of the epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages without visible basal layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate; (5) Normal mast cell count.Vega M. et al showed that EDP and LPP are very different entity through a study in which the clinical and histopathologic characteristics of patients with ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus were analyzed. The author founded significant clinical differences between the two diseases. (15)The proposed diagnostic criteria for EDP and IEMP are actually inconclusive. There is a wide area of overlap between the two entities. The inflammatory stage of EDP is not constant as well as the erythematous border.Similarly, the eruptive nature of IEMP is questionable. The age of incidence of IEMP is not distinctive and the condition has been reported in older age groups. (16) On the other hand, EDP has been reported in children as well. (4) The clinical presentations for both entities show a similar area of overlap. These facts encourage us to deal with these entities as parts of the same spectrum and we propose the term Idiopathic macular pigmentation for (EDP, Ashy Dermatosis and IEDMP). This study aimed to set the limits for idiopathic circumscribed hyperpigmentation of the hidden area in a practical easily applicable approach. The new approach depends mainly on the histopathological findings. Two main spectra were proposed. Patients with inflammatory element were classified in the LPP spectrum; while patients who lack the inflammatory reaction in the histopathology were classified as IMP spectrum.According to Sanz de Galdeano C et al Erythema dyschromicum perstans is mainly observed in intermediate skin types. It is a disease of young adults, although there are small series reporting the disease in prepubertal children. (14)Mehta S et al reported a 24-year-old woman with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation lasting 21 years was characterized by several periods of spontaneous resolution followed by recurrences. (17) In the other hand Torrelo A et al reported 14 cases of EDP in children aged 10 years and younger the sample size was large enough to document the occurrence of EDP in children. (4)LPP usually affecting adults, but rare in children a fact that was documented in this study by reporting the age of onset of patient with LPP to be between 20-29 years old in 4 patients (40%), while in the other 6 patients (60%) was more than 30 years old. (17) There appears to be no gender predilection in case of LPP according to Pannell R. S. (18) There is no clear sexual predilection in case of EDP as described by Sanz de Galdeano C et al.13 These results were similar to that in our study, as both group (LPP and IMP) showed equal male to female ratio with very slight male predilection in IMP group.The duration of the pigmented lesion in LPP at presentation ranged from 2 months to 21 years in one series achieved by Kanwar A. J. et al this finding were comparable to our study in which the duration in LPP group ranged between 2-94 months with a median of 30 months. (19)In erythema dyschromicum perstans the clinical course in childhood (prepubertal) may differ from that of adults; erythema dyschromicum perstans may be more likely to resolve within 2-3 years. (20)Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation reported to be self-limiting and disappears spontaneously in months to years. (18) We showed that the duration for IMP was between 2-48 months with a median of 17 months, collectively the disease duration for both EDP and IEMP where similar in the previous report and the present work, which rises the similarities between the two.The lesions color in LPP patients founded to be with violaceous hue in 8 (80%) patients and bluish hue in 2 (20%) patients, Kanwar AJ et al previously described that the color of LPP varies from slate grey to brownish black and the commonest type of pigmentation is a bluish black one. Other types are slate gray, dark brown and brownish black. (19)In ashy dermatosis the disease is characterized by hyperpigmented macules and patches of variable shape and size with an ashen-gray to brown-blue color. (14) Jang KA described the color of lesions in IEMP, skin lesions of 8 patients were multiple brown macules involving the trunk, face, neck, and extremities. In two patients, multiple dark brown macules and patches were noted. (18) We observed that the color spectrum of lesions in IMP group were nine (69.23%) patients had a slate blue versus four (30.77%) patients had brownish color neither one of them shows an erythematous border. From above we can conclude that both diseases had a color ranged between gray, blue, brown and black or could be mixed.In LPP, the macular hyperpigmentation involves chiefly the face, neck and upper limbs, although it can be more widespread. (19) Occasionally, there is a striking predominance of lesions at intertrigenous sites, especially the axillae. (21) The present work showed predilection of the LPP to the following sites: abdomen six (60%) patients, thigh eight (80%) patients, arms 7 (70%) patient, axillae 7 (70%) patients, face 4 (40%) patients, hands 3 (30%) patients, and feet 3 (30%) patients.In EDP the commonest site of involvement is on the proximal and distal aspects of the arms, neck, abdomen, and face, in an essentially symmetric distribution, the present work showed that the predilection site of IMP were: chest 10 (77%) patients, abdomen 11 (85%) patients, thigh 4 (31%) patients, arms 5 (38%) patient, back 2 (15%) patients and the flexures 2 (15%) patients, without involvement of the face, hands, and feet. (22)In LPP the skin type usually of skin type III to IV, while in EDP the skin type is of skin type III to IV. (23)A similar result obtained here, in LPP spectrum 2 (20%) patients skin type III, 5 (50%)patients skin type IV, & 3 (30%) patients skin type V , while in IMP spectrum 7 (53.8%) patients skin type III and 6 (46.2%)patients skin type V.Histologically, the main difference between the two groups was in the presence of inflammatory response in lesions of LPP, and absent in IMP. These results are consistent with that of Sebbag N. et al who showed that the inactive lesions of EDP, there is no vacuolization of the basal cell layer, a diminished dermal infiltrate, and an increased number of dermal melanophages. (4), (24)Migagawa S. et al described that the active border of EDP shows vacuolar degeneration of the basal cells and the epidermis contains much pigment with pigmentary incontinence, the dermal vessels sleeved with an infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, and there are many melanophages, mention that biopsy taken from the active border of lesions. (25)The present work show histopathological finding of dermal melanophages 12 (52.17%) patients, basal cell layer hyperpigmentation 10 (43.47%) patients and liquefaction degeneration 6 (26.08%) patients, which are not quit similar to that of Migagawa S. et al since there is no any inflammatory border in all cases of IMP group despite that some of the cases had similar criteria that used to describes ashy dermatosis first by Ramirez in 1957 and still in the acute phase at time of biopsy, those how failed to show the inflammatory border clinically and hence inflammatory infiltrate histopathologically. (26) This difference might also be explained by the difference in the patient selection and categorization.Response to treatment in the LPP group was No or minimal in 2 (20%) patients, Moderate 2 (20%) patients, and Good – Excellent 6 (60%) patients Follow up of patients with IMP (who were not received any treatment) through a 12 months duration shows No or minimal in 3 (23.07%) patients, Moderate 4 (30.7%) patients, and Good – Excellent 6 (46.1%) patients.In EDP, although spontaneous clearing can occur, especially in prepubertal children (~70% within 2–3 years), the lesions usually persist for years in adults, we found that patients with IMP (who were not received any treatment) through a 12 months duration shows No or minimal in 3 (23.07%) patients, Moderate 4 (30.7%) patients, and Good – Excellent 6 (46.1%) patients. (23)Twelve months later, second biopsy done for 2 (8.6%) patients with LPP and 3 (13.04%) patients with IMP, those patients how failed to show progress 4 (17.3) patients had Basal cell layer pigmentation and 3 (13.04%) Dermal melanophages. Patients with IMP spectrum In conclusion, patients with idiopathic circumscribed hyperpigmentation reveal an inflammatory infiltrate in the biopsy specimens would be diagnosed as LPP. This will eventually include the inflammatory variant of EDP. On the other hand, patients with unexplainable pigmentations in the hidden area with no demonstrable inflammation in the histopathology would be diagnosed as IMP. This will include non inflammatory variant of EDP, Ashy dermatosis, and IEMP.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML