| [1] | Wolf R, Matz H, Orion E, 2004, Acne and diet. Clin Dermatol.; 22 (5): 387-93. |

| [2] | Thappa DM., 2009, Profile of acne vulgaris – a hospital – based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol; 73 (3): 272-8. |

| [3] | El-Akawi Z, Abdel-Latif Nemr N, Abdul-Razzak K, 2006, Factors believed by Jordanian acne patients to affect their acne condition. East Mediterr Health J; 12 (6): 840-6. |

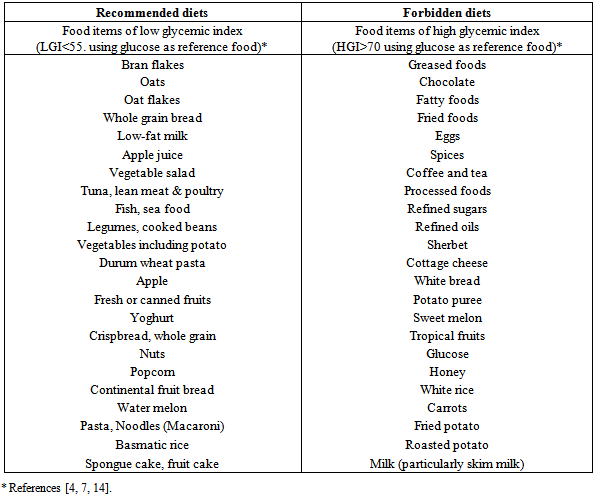

| [4] | Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, Mann NJ, 2008, The effect of low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglyceride. J Dermatol Sci; 50: 41-52. |

| [5] | Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, Makelainen H, Vargios GA, 2007a, A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr; 86: 107-15. |

| [6] | Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, Makelainen H, Vargios GA, 2007b, The effect of a high-protein, low-glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high-glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: A randomized, investigator – masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol; 57: 247-56. |

| [7] | Cordian L, 2005, Implications for the role of diet in acne. Semin Cutan Med Surg; 24: 84-91. |

| [8] | Bowe WP, Joshi SS, Shalita AR. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010 ; 23: 1-18. |

| [9] | Webester GE, 2008, Commentary: Diet and acne. J Am Dermatol; 58: 794-5. |

| [10] | Ferdowsian HR, Levin S, 2010, Does diet really affect acne? Skin Therapy Letter; 15 (3): 1-2. |

| [11] | Abdel-Hafez K, Mahran AM, Hofny ERM, Mohammed KA, Darweesh AM, Aal AA, 2009,The impact of acne vulgaris on the quality of life and psychologic status in patients from Upper Egypt. Int J Dermatol; 48: 280-285. |

| [12] | Kaymak Y, Adisen E, Bideci A, 2007, Dietary glycemic index and glucose, insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 and leptin levels in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol; 57: 819-23. |

| [13] | Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, 2008, Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol; 58 (5): 787-93. |

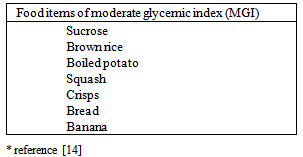

| [14] | Stear S, 2001, Carbohydrates in diabetes: Optimizing glycaemic control. Community Nurse; 15-16. |

| [15] | Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, Danby FW, Rockett HH, Colditz GA, 2006, Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol Online J; 12: 1. |

| [16] | Cordian L, Lindeberg S., Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton B, Brand-Miller B, 2002, Acne vulgaris – a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol; 138: 1584-90. |

| [17] | Schaefer O, 1971, When the Eskimo comes to town. Nutr Today; 6: 8-16. |

| [18] | Pochi PE, Shalita AR, Strauss JS. Report of the consensus conference on acne classification 1991; 24: 495-500. |

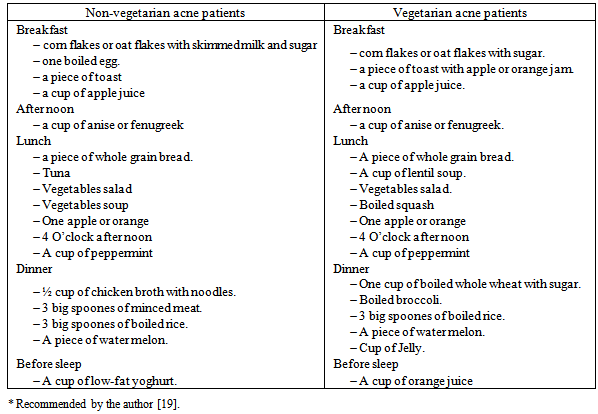

| [19] | Youssef MKE. Recommended dietary regimen for acne patients. Food Sci & Tech. Assiut Univ. 2011. |

| [20] | SAS Institute Inc, editor. SAS/Stat 9.1 User's Guide. Cary, NC. USA, 2004 |

| [21] | World Health Organization, editor. Measuring obesity: classification and description of anthropometric data. Report on a WHO Consultation on the Epidemiology of obesity. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Nutrition Unit; 1989. |

| [22] | Gronder M, Anderson SL and De Young S, editors. Foundations and applications of nutrition. A nursing approach. M Mosby. St Louis. USA; 1996. |

| [23] | Thiboutot D, Strauss J, 2002, Diet and acne revisited. Arch Dermatol; 138: 1591-2. |

| [24] | Balch JF, Balch PA, editors. Prescription for nutritional healing. Second Edition. 88-91. New York: Avery Publishing Group. Garden City Park; 1997. |

| [25] | Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, Ingordo V, Cusano F, and Atzori L, 2012, Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol.; 67 (6); 1129-35. |

| [26] | Koku Aksu AE, Metintas S, Saracoglu ZN, Gurel G, Sabuncu I, and Arikan I, 2011, Acne: prevalence and relationship with dietary habits in Eskisehir, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.; 26 (12):1503-9. |

| [27] | Fulton J, Plewig G, Kligman A, 1969, Effect of chocolate on acne vulgaris. JAMA; 210: 2171-4. |

| [28] | Mackie B, Mackie L, 1974, Chocolate and acne. Aust J Dermatol; 15: 103-9. |

| [29] | Anderson P, 1971, Foods as the cause of acne. Am J Fam Pract; 13: 102-3. |

| [30] | Adebamowo C, Spiegelman D, Danby F, Fraizer A, Willett W, Holmes M, 2005, High school dietary intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol; 52: 207-14. |

| [31] | Spencer EH, Ferdowsian HR, Barnard ND, 2009, Diet and acne: a review of the evidence. Int J Dermatol; 48 (4): 339-47. |

| [32] | Grant JD, Anderson PC, 1965, Chocolate as a cause of acne: a dissenting view. Mo Med; 62: 459-60. |

| [33] | Crawford G, Swartz J, 1936, Acne and the carbohydrate. Arch Dermatol Supl.; 33: 1036-40. |

| [34] | Cornbleet T, Gigli I, 1961 Should we limit sugar in acne? Arch Dermatol; 83: 968-70. |

| [35] | Rouhani P, Berman I, Frayn G. Acne improves with a popular, low glycermic diet from Souch Beach. 67th Annual Meeting of American Academy of Dermatology. Poster 706. San Francisco. 2009. |

| [36] | Smith R, Mann N, Makelainen H, Roper J, Braue A, Varigos G, 2008, A pilot study to determine the short-term effects of a low glycemic load diet on hormonal marker of acne: a non-randomized, parallel, controlled feeding trial. Mol Nutr Food Res.; 52: 718-26. |

| [37] | Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, Jung JY, Park MS, Suh DH, 2012, Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol.; 92 (3):241-6. |

| [38] | Paoli A, Grimaldi K, Toniolo L, Canato M, Bianco A, Fratter A, 2012, Nutrition and acne: therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets. Skin Pharmacol Physiol.; 25 (3):111-7. |

| [39] | Melnik BC, 2012, Diet in acne: further evidence for the role of nutrient signaling in acne pathogenesis - a commentary. Acta Derm Venereol; 92 (3): 228-31. |

| [40] | Melnik BC, John SM, Plewig G, 2013, Acne: risk indicator for increased body mass index and insulin resistance. Acta Derm Venereol; 93 (6): 644-9. |

| [41] | Kligman AM, Mills OH Jr, Leyden Jr, Gross PR, Allen HB, Rudolf RI, 1981, Oral vitamin A in acne vulgaris: Preliminary report. Int J Dermatol; 20: 275-285. |

| [42] | Dreno B, Moyse D, Alirezai M, Amblard P, Auffret N, Beylot C, 2001, Multicenter randomized comparative double-blind controlled critical trial of the safety and efficacy of zinc gluconate versus minocycline hydrochloride in treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. Dermatology; 303: 135-140. |

| [43] | Brand-Miller J, Thomas M, Swan V, Ahmad Z, Petocz P, Colagiuri S, 2003, Physiological validation of the concept of glycemic load in lean young adults. J Nutr; 133: 2728-32. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML