-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics

p-ISSN: 2165-8935 e-ISSN: 2165-8943

2014; 4(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.ajcam.20140401.01

A Comprehensive Analysis on Dissections of Continued Fractions

Roselin Antony

Department of Mathematics, College of Natural and Computational Sciences, Mekelle University, Mekelle, P.O. Box 231, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Roselin Antony, Department of Mathematics, College of Natural and Computational Sciences, Mekelle University, Mekelle, P.O. Box 231, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Continued fraction is one of the form of expressing any numbers or functions. Though the origin of continued fractions is hard to pinpoint, its algorithms were used by mathematicians during 4th century B.C. – 3rd century A.D. But its true foundations were not laid until the late 1600's, early 1700's. Continued fractions became a field in its right, in the beginning of 18th century. In the intervening years, many researchers studied and analyzed Continued fractions in different angles and many researcher papers have appeared in journals. This work is a survey of studies on dissections of continued fractions conducted by different mathematicians from the beginning till the 21st century.

Keywords: Continued fractions, Dissections, Cubic continued fraction

Cite this paper: Roselin Antony, A Comprehensive Analysis on Dissections of Continued Fractions, American Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics , Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.ajcam.20140401.01.

1. Introduction

- Continued fractions play an important role in expressing numbers and functions. But, in the early ages, 300 B.C. – 200 A.D., mathematicians used other algorithms and methods to express numbers and to express solutions of Diophantine equations. Many of these algorithms were studied and modeled in the development of the continued fractions. Through the eighteenth century, use of continued fractions was limited to the field of mathematics.The origin of continued fractions is hard to pinpoint. This is due to the fact that we can find examples of these fractions throughout mathematics in the last 2000 years, but its true foundations were not laid until the late 1600's, early 1700's. The origin of continued fractions is traditionally placed at the time of the creation of Euclid's Algorithm. Euclid's Algorithm, however, is used to find the greatest common denominator (g.c.d) of two numbers. However, by algebraically manipulating the algorithm, one can derive the simple continued fraction of the rational p/q as opposed to the g.c.d of p and q. It is doubtful whether Euclid or his predecessors actually used this algorithm in such a manner. But due to its close relationship to continued fraction, the creation of Euclid's Algorithm signifies the initial development of continued fractions.For more than a thousand years, any work that used continued fractions was restricted to specific examples. The Indian mathematician Aryabhata (550 AD) used a continued fraction to solve a linear indeterminate equation[1]. Rather than generalizing this method, his use of continued fractions is used solely in specific examples.Throughout Greek and Arab mathematical writing, we can find examples and traces of continued fractions. But again, its use is limited to specifics. Indian scholar Narayana (1350 A. D.)[2] perhaps used the result

and

and  of the continued fraction to find out the integral solution of the equation

of the continued fraction to find out the integral solution of the equation  . The paper presents the original Sanskrit verses (in Roman Character) with English translation from Narayana's Ganita Kaumudi.Two men from the city of Bologna, Italy, Rafael Bombelli (1530 A.D.) and Pietro Cataldi (1548-1626)[1] also contributed to this field, albeit providing more examples. Bombelli expressed the square root of 13 as a repeating continued fraction. Cataldi did the same for the square root of 18. Besides these examples, however, neither mathematician investigated the properties of continued fractions. Continued fractions became a field in its right through the work of John Wallis (1616-1703)[1, 3]. In his book Arithemetica Infinitorium (1655), he developed and presented the identity

. The paper presents the original Sanskrit verses (in Roman Character) with English translation from Narayana's Ganita Kaumudi.Two men from the city of Bologna, Italy, Rafael Bombelli (1530 A.D.) and Pietro Cataldi (1548-1626)[1] also contributed to this field, albeit providing more examples. Bombelli expressed the square root of 13 as a repeating continued fraction. Cataldi did the same for the square root of 18. Besides these examples, however, neither mathematician investigated the properties of continued fractions. Continued fractions became a field in its right through the work of John Wallis (1616-1703)[1, 3]. In his book Arithemetica Infinitorium (1655), he developed and presented the identity  The first president of the Royal Society, Lord Brouncker (1620-1684) transformed this identity into

The first president of the Royal Society, Lord Brouncker (1620-1684) transformed this identity into  Though Brouncker did not dwell on the continued fraction, Wallis took the initiative and began the first steps to generalizing continued fraction theory. In his book Opera Mathematica (1695) Wallis laid some of the basic groundwork for continued fractions. He explained how to compute the nth convergent and discovered some of the now familiar properties of convergents. It was also in this work that the term "continued fraction" was first used.The Dutch mathematician and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695)[1, 4] was the first to demonstrate a practical application of continued fractions. He wrote a paper explaining how to use the convergents of a continued fraction to find the best rational approximations for gear ratios. These approximations enabled him to pick the gears with the correct number of teeth. His work was motivated impart by his desire to build a mechanical planetarium.While the work of Wallis and Huygens began the work on continued fractions, the field of continued fractions began to flourish when Leonard Euler (1707-1783), Johan Heinrich Lambert (1728-1777), and Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736-1813) embraced the topic. Euler laid down much of the modern theory in his work De Fractionlous Continious (1737). He showed that every rational can be expressed as a terminating simple continued fraction. He also provided an expression for e in continued fraction form. He used this expression to show that e and e2 are irrational. He also demonstrated how to go from a series to a continued fraction representation of the series, and conversely.Lambert generalized Euler's work on e to show that both ex and tan x are irrational if x is rational[3]. Lagrange used continued fractions to find the value of irrational roots. He also proved that a real root of a quadratic irrational is a periodic continued fraction. The nineteenth century can probably be described as the golden age of continued fractions. As Claude Brezinski[5] writes in History of Continued Fractions and Padre Approximations, "the nineteenth century can be said to be popular period for continued fractions." It was a time in which "the subject was known to every mathematician." As a result, there was an explosion of growth within this field. The theory concerning continued fractions was significantly developed, especially that concerning the convergents. Some of the more prominent mathematicians to make contributions to this field include Jacobi, Perron, Hermite, Gauss, Cauchy, and Stieljes[4]. By the beginning of the 20th century, the discipline had greatly advanced from the initial work of Wallis.Since the beginning of the 20th century continued fractions have made their appearances in other fields. This brief sketch into the past of continued fractions is intended to provide an overview of the development of this field. Though its initial development seems to have taken a long time, once started, the field and its analysis grew rapidly. Srinivasa Ramanujan, an Indian Mathematician had an extreme fondness for continued fractions. He expressed continued fractions in terms of infinite products. Andrews[6] represented these infinite product representations of continued fractions in terms of dissections which paved the way for further developments in dissections.In the intervening years, several studies have been conducted on dissections of continued fractions and many research papers have been published. This paper gives a brief note on the developments of dissections of continued fractions in the field of Mathematics.

Though Brouncker did not dwell on the continued fraction, Wallis took the initiative and began the first steps to generalizing continued fraction theory. In his book Opera Mathematica (1695) Wallis laid some of the basic groundwork for continued fractions. He explained how to compute the nth convergent and discovered some of the now familiar properties of convergents. It was also in this work that the term "continued fraction" was first used.The Dutch mathematician and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695)[1, 4] was the first to demonstrate a practical application of continued fractions. He wrote a paper explaining how to use the convergents of a continued fraction to find the best rational approximations for gear ratios. These approximations enabled him to pick the gears with the correct number of teeth. His work was motivated impart by his desire to build a mechanical planetarium.While the work of Wallis and Huygens began the work on continued fractions, the field of continued fractions began to flourish when Leonard Euler (1707-1783), Johan Heinrich Lambert (1728-1777), and Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736-1813) embraced the topic. Euler laid down much of the modern theory in his work De Fractionlous Continious (1737). He showed that every rational can be expressed as a terminating simple continued fraction. He also provided an expression for e in continued fraction form. He used this expression to show that e and e2 are irrational. He also demonstrated how to go from a series to a continued fraction representation of the series, and conversely.Lambert generalized Euler's work on e to show that both ex and tan x are irrational if x is rational[3]. Lagrange used continued fractions to find the value of irrational roots. He also proved that a real root of a quadratic irrational is a periodic continued fraction. The nineteenth century can probably be described as the golden age of continued fractions. As Claude Brezinski[5] writes in History of Continued Fractions and Padre Approximations, "the nineteenth century can be said to be popular period for continued fractions." It was a time in which "the subject was known to every mathematician." As a result, there was an explosion of growth within this field. The theory concerning continued fractions was significantly developed, especially that concerning the convergents. Some of the more prominent mathematicians to make contributions to this field include Jacobi, Perron, Hermite, Gauss, Cauchy, and Stieljes[4]. By the beginning of the 20th century, the discipline had greatly advanced from the initial work of Wallis.Since the beginning of the 20th century continued fractions have made their appearances in other fields. This brief sketch into the past of continued fractions is intended to provide an overview of the development of this field. Though its initial development seems to have taken a long time, once started, the field and its analysis grew rapidly. Srinivasa Ramanujan, an Indian Mathematician had an extreme fondness for continued fractions. He expressed continued fractions in terms of infinite products. Andrews[6] represented these infinite product representations of continued fractions in terms of dissections which paved the way for further developments in dissections.In the intervening years, several studies have been conducted on dissections of continued fractions and many research papers have been published. This paper gives a brief note on the developments of dissections of continued fractions in the field of Mathematics.2. Dissections of Continued Fractions

- The Rogers - Ramanujan continued fraction is,

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

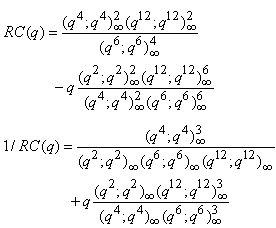

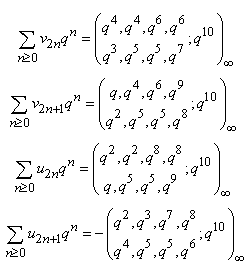

.The 2-dissections of R(q) and R(q)-1 were given by Andrews[6]. The following are the 2-dissections,

.The 2-dissections of R(q) and R(q)-1 were given by Andrews[6]. The following are the 2-dissections,  | (2.3) |

| (2.4) |

| (2.5) |

| (2.6) |

| (2.7) |

| (2.8) |

| (2.9) |

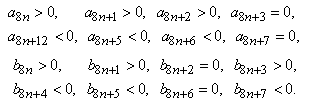

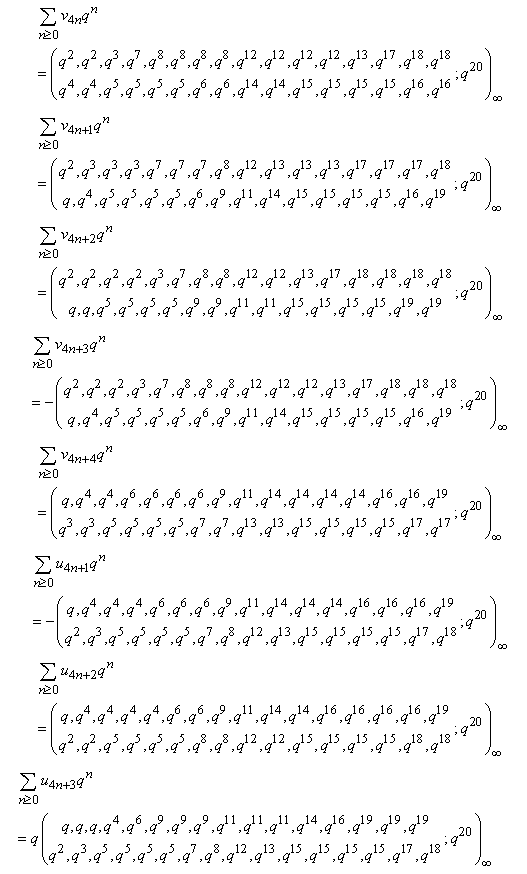

,

, .Hirschhorn proved the following theorem;For

.Hirschhorn proved the following theorem;For

| (2.10) |

| (2.11) |

Ramanujan[19] states that

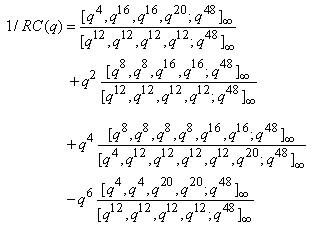

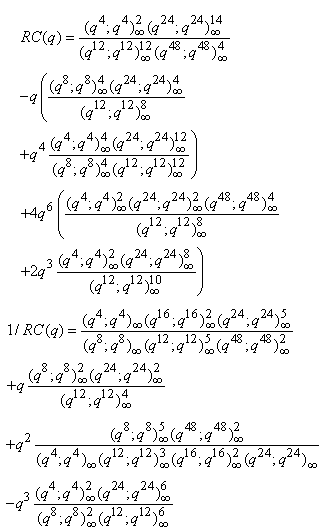

Ramanujan[19] states that  Bhaskar Srivastava[18] gave the following 2-, 4-dissections of 1/RC (q) by using a famous theorem of Lewis and Liu[9].The 2-dissection of 1/RC(q) is

Bhaskar Srivastava[18] gave the following 2-, 4-dissections of 1/RC (q) by using a famous theorem of Lewis and Liu[9].The 2-dissection of 1/RC(q) is | (2.12) |

| (2.13) |

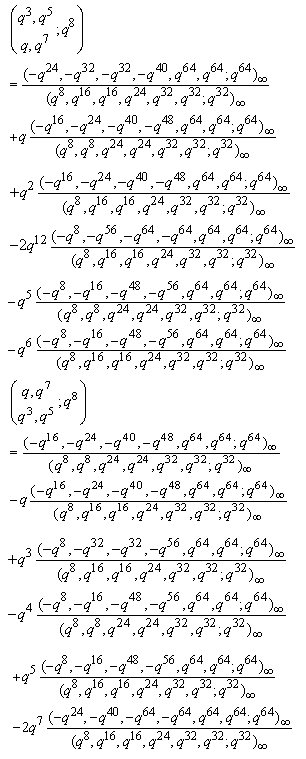

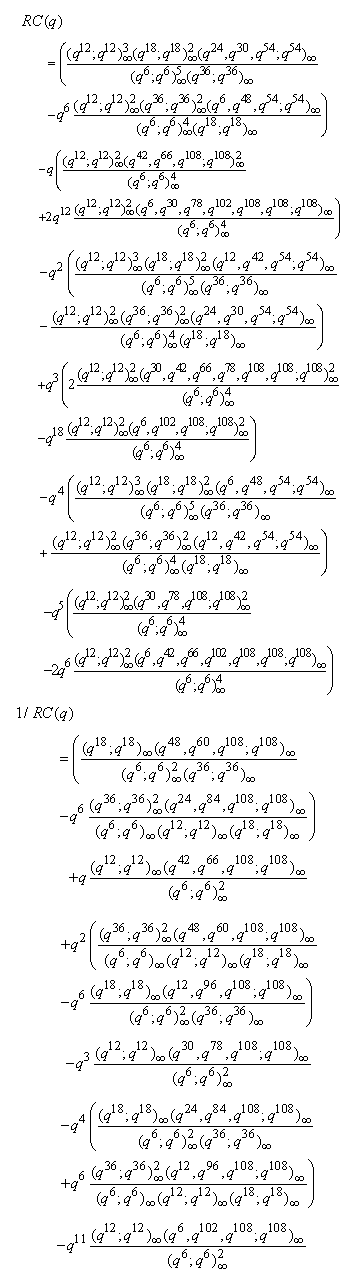

Hirschhorn and Roselin Antony[20] gave the following 2-, 3-, 4-, 6-dissections of Ramanujan’s cubic continued fraction and its reciprocal.The 2-dissections of RC(q) and its reciprocal are given by

Hirschhorn and Roselin Antony[20] gave the following 2-, 3-, 4-, 6-dissections of Ramanujan’s cubic continued fraction and its reciprocal.The 2-dissections of RC(q) and its reciprocal are given by | (2.14) |

| (2.15) |

| (2.16) |

| (2.17) |

then

then | (2.18) |

| (2.19) |

3. Conclusions

- In the foregoing sections, results concerning dissections of various continued fractions are presented. However, there are other continued fractions for which dissections are not yet given by researchers. Many researchers have worked on dissections and studied the periodicity of the coefficient. We believe that these results can further be extended for higher dissections of various continued fractions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML