-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Biochemistry

p-ISSN: 2163-3010 e-ISSN: 2163-3029

2023; 13(1): 8-13

doi:10.5923/j.ajb.20231301.02

Received: Sep. 16, 2023; Accepted: Oct. 9, 2023; Published: Oct. 13, 2023

Assessment of Metabolic Syndrome in Subjects with Cryptogenic Stroke

Moustapha Djite1, 2, Mame Ndoumbé Mbacke2, Ndiaga Matar Gaye3, Siny Ndiaye2, Néné Oumou Kesso Barry1, 2, Ousmane Cisse3, Pape Matar Kandji1, 2, Ndèye Marème Thioune2, Najah Fatou Coly-Gueye4, El Hadji Malick Ndour1, Fatou Gueye-Tall1, Dominique Doupa, Amadou Gallo Diop3, Papa Madieye Gueye1, 2

1Pharmaceutical Biochemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal

2Biochemistry Laboratory, Fann National University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal

3Neurological Clinic, Fann National University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal

4Diamniadio Children's Hospital, Dakar, Senegal

Correspondence to: Moustapha Djite, Pharmaceutical Biochemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

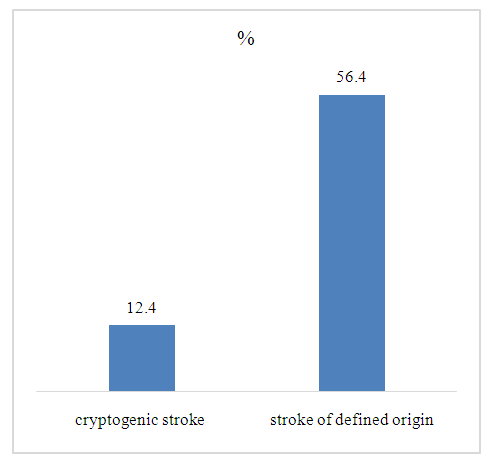

Background: Stroke is a failure of blood circulation that affects a more or less important region of the brain. It presents several risk factors, among which metabolic abnormalities seem to occupy a prominent place in its occurrence. Aim of study: The general objective of our study was to evaluate the metabolic syndrome in patients with cryptogenic stroke. Methods: This was a case-control study involving patients with stroke of cryptogenic origin. Patients were recruited from the neurological clinic at Fann National University Hospital, and biological tests were performed in the biochemistry laboratory. Metabolic syndrome was sought in our entire study population according to National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP ATP III) definition criteria. Results: Our study included 40 subjects with stroke of cryptogenic origin and 40 control subjects with strokes of defined cause. The mean age of the patients was 46 years, with a sex ratio of 1.35. Analysis of the clinical data had shown that the frequencies of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia were much higher in stroke of definite cause. Evaluation of the metabolic syndrome revealed frequencies of 12.5% and 56.4% respectively in subjects with cryptogenic stroke and in subjects with stroke of determined cause according to NCEP criteria. Conclusion: The results showed that subjects with stroke of cryptogenic origin had fewer cardiovascular risk factors than those with stroke of definite cause. In addition, significant frequencies of metabolic syndrome determinants were found in stroke of cryptogenic origin. Early detection and regular monitoring of metabolic syndrome in young subjects is therefore essential.

Keywords: Stroke, Cryptogenic stroke, Metabolic syndrome, Hypertension, Diabetes

Cite this paper: Moustapha Djite, Mame Ndoumbé Mbacke, Ndiaga Matar Gaye, Siny Ndiaye, Néné Oumou Kesso Barry, Ousmane Cisse, Pape Matar Kandji, Ndèye Marème Thioune, Najah Fatou Coly-Gueye, El Hadji Malick Ndour, Fatou Gueye-Tall, Dominique Doupa, Amadou Gallo Diop, Papa Madieye Gueye, Assessment of Metabolic Syndrome in Subjects with Cryptogenic Stroke, American Journal of Biochemistry, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 8-13. doi: 10.5923/j.ajb.20231301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Stroke is a major public health problem. It is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "the rapid development of localized or global clinical signs of cerebral dysfunction with symptoms lasting more than 24 hours that can lead to death with no apparent cause other than vascular [1]. There are two types of stroke: hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke. Previously, strokes occurred mainly in subjects aged over 60, but currently a paradigm shift has been noted in its epidemiology and we observe its occurrence more and more in subjects under 40. Indeed, in the TOAST classification, there is a sub-type of stroke that occurs mainly in young subjects, accounting for 40% of strokes overall [2]. In this classification, cryptogenic stroke of is defined by the absence of an etiology, despite full exploration. Some 25% to 50% of stroke in young adults remain of cryptogenic origin. In the United States, more than 750,000 people are thought to suffer strokes annually, a third of which are cryptogenic [3]. In Senegal, there are no official statistical on this type of stroke.Today, several diagnostic hypotheses have been put forward. Non-obstructive atheromatous lesions (stenosis < 50%), patent foramen ovale and aneurysm of the inter-atrial septum are said to be the most frequent of the so-called uncertain causes [4]. In addition, studies have shown that cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and dyslipidemia are occurring earlier and earlier in young subjects. And this is due to changes in people's lifestyles, which are becoming increasingly precarious. This could lead to the early onset of metabolic syndrome. The latter, is a set of conditions that combine and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases including stroke [5]. Metabolic syndrome has become a global health issue due to its increasing prevalence and association with cardiovascular disease. The exact prevalence of metabolic syndrome varies from country to country due to differences in population characteristics, lifestyle factors and genetic predisposition. As a result, metabolic syndrome can occur at any age, and may be behind a stroke of cryptogenic origin in young adults. It is in this context that we set ourselves the general objective of evaluating the metabolic syndrome in subjects suffering from stroke of cryptogenic origin at the National University Hospital Centre of Fann.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

- This is a case-control study of subjects with cryptogenic ischemic stroke. Patients were recruited from the neurological clinic of the National University Hospital Centre of Fann (CHNU/FANN) in Dakar. Biochemical parameters were assayed in the biochemistry laboratory of the said structure.

2.2. Study Participants and Sampling

- Our study included 40 subjects with cryptogenic stroke, according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification, known as Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ESUS) [6]. Stroke was diagnosed on clinical grounds and confirmed by imaging data in all patients, and cryptogenic origin was confirmed by the absence of high-risk emboligenic heart disease and stenosing (>50%) extra- or intracranial atheroma. Subjects with stroke related to patent foramen ovale-interatrial septal aneurysm (PFO-ASIA), non-stenosing (<50%) potentially embolic atheroma, dissection, vasculitis and small cerebral artery disease (≤2.0 cm) were not included in the study. Two groups of control subjects were recruited, and blood samples were taken under the same conditions as subjects with cryptogenic stroke. The first group of control subjects consisted of 40 subjects with stroke of definite cause followed in the same neurology department. The second group of control subjects consisted of 40 healthy subjects with no clinically apparent pathologies recruited from blood donor subjects. Blood sampling was performed under the same conditions for all subjects in the study population. Blood was collected from each subject in a lithium heparinate tube, a dry tube and an EDTA tube. They were immediately transported on ice to the laboratory, then handled or stored at -20°C until the day of handling.

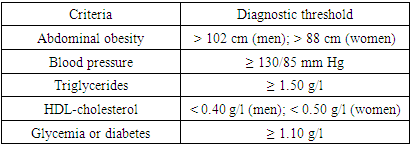

2.3. Data Collection

- Biochemical parameters were determined by enzymatic methods in accordance with suppliers' recommendations. The Architect ci4100 (Abbot, USA) system was used. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Fridewald formula. Metabolic syndrome was defined in this study according to NCEP ATP III criteria. (see Table 1) [7].

|

2.4. Data Analysis

- XLSTAT version 2021 was used to process the data. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare means, and the Chi2 test to compare frequencies. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

- This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (“Comité d'éthique de la recherche – CER”) of Cheikh Anta Diop University (UCAD) in accordance with the rules laid down by Senegal's National Health Research Ethics Committee under number: 0412/2019/CER/UCAD.

3. Results

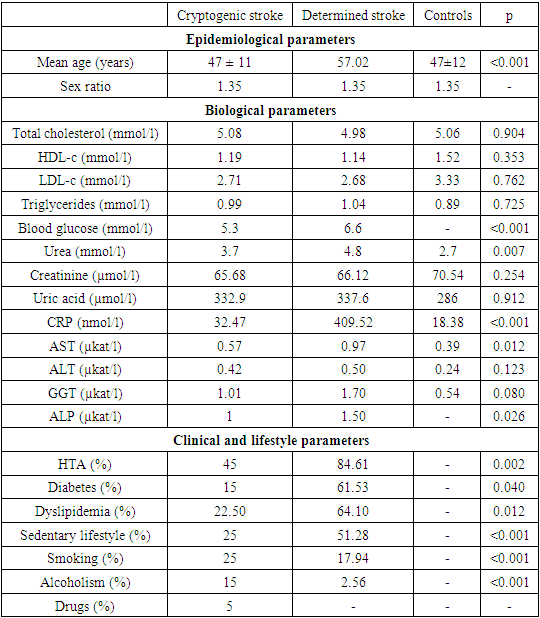

- Our study included 40 subjects with cryptogenic stroke, 40 subjects with stroke of determined origin and 40 healthy control subjects. The mean age of the cryptogenic ischemic stroke group (47 years) was 10 years younger than that of the determined ischemic stroke group (57 years, p < 0.001). The sex ratio (1.35) was similar between the three groups. With regard to biological analyses, the cryptogenic stroke group had significantly lower blood levels of glucose, urea, C-reactive protein, AST and alkaline phosphatase than stroke control group of defined origin. Lipids, creatinine and other liver enzymes were comparable between the two groups. Clinically, the cryptogenic stroke group was significantly less affected by hypertension, diabetes and history of dyslipidemia than stroke control group of defined origin. However, the cryptogenic stroke group had significantly higher tobacco, alcohol and drug consumption than the stroke control group of defined origin (see Table 2).

|

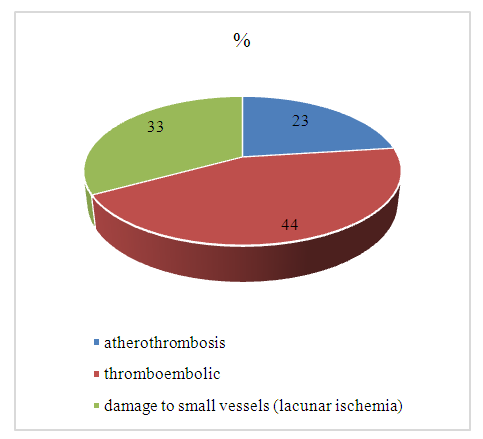

| Figure 1. Etiologies of stroke of known origin in the study population |

| Figure 2. Evaluation of metabolic syndrome in subjects with cryptogenic and determined stroke |

|

|

4. Discussion

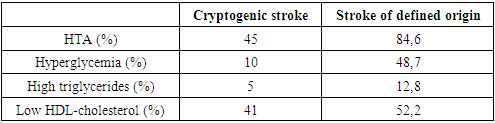

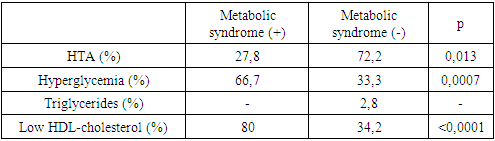

- Cryptogenic stroke is a stroke whose cause is unknown or undetermined despite full evaluation. The presence of traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia are not sufficient to explain the occurrence of these strokes. However, studies have shown that the metabolic syndrome may be involved in the pathogenesis of cryptogenic stroke [8]. According to a systematic review published in 2013, the estimated prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Senegalese adults was around 15% [9]. Some studies suggest that prevalence is higher in America, the Middle East and parts of Europe than in regions such as Africa and Southeast Asia. Specific data on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Senegal are limited, but studies have indicated that metabolic syndrome is clearly on the rise in the country. This could be a justifying factor for the increase in cardiovascular disease especially in younger subjects.Our results had showń in cryptogenic stroke an earlier age of onset compared to other subtypes. The mean age was 46 years for cryptogenic strokes versus 56 years for strokes of determined origin. Similar results were found by Hart and col. in 2000 with mean ages of 61 and 68 respectively for cryptogenic and known-cause strokes [10]. Other studies carried out in China have found́ similar results [11]. Indeed, the process of atherosclerosis begins very early on with discrete endothelial lesions that worsen increasingly with age and culminate, in the absence of appropriate treatment, in the formation of an atheromatous plaque that can thus be the cause of a stroke [12]. Evaluation of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with cryptogenic stroke revealed a frequency of 12.5%. This was confirmed in a Cameroonian study by Mapoure Y and col. [13]. Other studies carried out just about everywhere (Tunisia, Iran, Turkey, Jordan...) have also found similar results. This suggests that the metabolic syndrome is a significant factor in exposure to cardiovascular disease, including cryptogenic stroke. However, differences in frequency were found in several studies. A retrospective study published in the "Journal of Stroke" in 2016 examined́ the frequency of metabolic syndrome in patients with cryptogenic stroke. Metabolic syndrome was present in 30% of their study population [14]. This frequency is almost three times higher than in our study. In addition, a meta-analysis published in "BMC Neurology" in 2017 examined́ the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with stroke. Metabolic syndrome was found in 33% of patients with cryptogenic stroke [15]. These differences can be explained on the one hand by the size of our study population, which is relatively small compared with other studies. On the other hand, we did not use the same criteria for defining metabolic syndrome. We used́ that of NCEP ATP III whereas elsewhere it is the WHO definition that is most widely used. However, it should be noted that the NCEP ATP III definition is more consensual and brings together more learned societies. Indeed, metabolic syndrome is associated with the development of atherosclerosis. The main determinant seems to be the increase in visceral fat, which induces an increase in free fatty acids to the liver, as well as insulin resistance. These two relays will themselves induce a cascade of abnormalities affecting numerous proatheromatous risk factors. These include hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, altered coagulation parameters leading to a prothrombotic state, insulin resistance, elevated CRP, activation of cytokines and adhesins, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress [16-18]. The metabolic syndrome is associated with several metabolic abnormalities, the end result of which is characterized by the accumulation of atheromatous plaques in the arteries. Metabolic syndrome has two main complications. On the one hand, we have cardiovascular disease, which is increased by a factor of 2 to 3, and on the other, the risk of progressing to type 2 diabetes, which will itself worsen this cardiovascular risk [13]. In addition, we can note that the high frequency of metabolic syndrome found in several studies is parallel to the increase in its determinants. Thus, in our study, hypertension was found in 84.61% of subjects with stroke of known cause, and in 45% of those with cryptogenic stroke. Similarly, Li Y, and col. also compared the frequency of hypertension between the two groups of patients. The results showed́ that the prevalence of hypertension was significantly higher in the group of strokes of determined origin (75.6%) than in the cryptogenic stroke group (54.2%) [19]. High blood pressure is not only an independent cardiovascular risk factor, but also a major determinant of metabolic syndrome. It can damage blood vessels, making them more likely to rupture or form blood clots.As far as diabetes is concerned, we found in subjects with cryptogenic stroke a rate of 15% versus 61.53% for determined stroke. In 2014 a study by Lee and col. had found́ similar results with a prevalence of diabetes that was significantly higher in patients with stroke of determined cause (38%) than in those with cryptogenic stroke (15.4%) [20]. It is now established that insulin resistance and diabetes, often part of the metabolic syndrome, can increase the risk of stroke. The chronic hyperglycemia associated with diabetes can damage blood vessels over time, increasing the likelihood́ of blood clots and stroke. Insulin resistance can also contribute to inflammation and vascular dysfunction, further increasing the risk of stroke.The results showed́ also higher prevalences of dyslipidemia in subjects with stroke of determined cause. A study published in 2012 in the journal "Neurology" by Nardi K and col. had showń significantly higher frequencies of dyslipidemia in patients with stroke of determined cause than in those with cryptogenic stroke [21]. Dyslipidemia contributes to the development of atherosclerosis and can affect blood flow to the brain, increasing the risk of stroke.

5. Conclusions

- The results of the study showed that subjects with cryptogenic stroke have fewer cardiovascular risk factors than those with stroke of determinate origin. However, the frequency of metabolic syndrome is not negligible, at 12.5%. Furthermore, the epidemiology of metabolic syndrome changes over time due to a variety of factors such as demographic changes, lifestyles and healthcare interventions. Thus, regular surveillance and research studies are essential to monitor the prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in order to inform public health strategies and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank all those who took part in this study, especially the neurology department at Fann Hospital.

Limitations of Study

- The main limitation of the study was the size of the sample, due in part to the nature of the population (cryptogenic stroke). problems of optimal patient follow-up made our recruitment difficult.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

- The study was fully funded by the Biochemistry Laboratory of the National University Hospital/Fann.

Conflicts of Interest

- The authors declare having no conflict of interest in related to this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML