-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Biochemistry

p-ISSN: 2163-3010 e-ISSN: 2163-3029

2017; 7(4): 55-62

doi:10.5923/j.ajb.20170704.01

Estimation of Serum Interferon Alpha and Toll-Like Receptors 3 (TLRs 3) Gene Expression in Egyptian Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

Sabah E. Abd-Elraheem1, Wafaa M. El-Zefzafy2

1Departments of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

2Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Sabah E. Abd-Elraheem, Departments of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine (for girls), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Liver cirrhosis is an end stage hepatic disarrangement. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), are important components of innate immune response that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and trigger immune responses. TLR3 signaling negatively regulates liver regeneration via stimulating NK cells to produce IFN. That could contribute to cirrhosis and HCC. Aim of the work: To determine the serum levels of IFN-α, TLR3 expression in Egyptian patients with liver cirrhosis as well as their correlation to other -biochemical parameters. Patients and methods: This study included 60 patients divided into 2 groups; group A: comprised 30 patients with pure HCV infection without cirrhosis, group B: comprised 30 patients with liver cirrhosis due to HCV infection together with 30 healthy control. The diagnosis was established on the basis of history, clinical, laboratory, abdominal ultrasound. CBC, ESR, liver, kidney function tests, HBS antigen & anti-HCV antibody, interferon α and TLR3 expression were also done. Results: There was highly significant increase of serum INF alpha levels in group (A) in comparison to group (B), and group (C), while there was significant difference when we compared (B) to group (C). There was no significant difference as regard TLR 3 gene expression by comparing group (A) and group (B), while by comparing group (A), and (B) with group (C) there was highly significant difference. There was significant positive correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (B), while there was no significant correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (A) also there was no significant correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and (Age, ALT, AST, ALB, Total Bilirubin, HB, PLT, TLC and viral load presence) neither in group (A) nor (B). Conclusion: The results of this study suggested that Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) is likely involved in early pathogen detection and the host response to HCV infection as well as in liver cirrhosis. There is significant positive correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in cirrhotic patients due to CHCV infection. The down regulation of TLR3 expression by HCV may contribute to the decrease of IFN-α in cirrhotic patients.

Keywords: Liver Cirrhosis, interferon α, TLR3

Cite this paper: Sabah E. Abd-Elraheem, Wafaa M. El-Zefzafy, Estimation of Serum Interferon Alpha and Toll-Like Receptors 3 (TLRs 3) Gene Expression in Egyptian Patients with Liver Cirrhosis, American Journal of Biochemistry, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 55-62. doi: 10.5923/j.ajb.20170704.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cirrhosis, a chronic diffuse lesion usually accompanying extensive liver fibrosis and nodular regeneration, is caused by liver parenchymal cells repeating injury-repair following reconstruction of organizational structure in the hepatic lobules. It is now recognized as essentially late-stage fibrosis that is triggered by repeated injury-inflammation caused by factors including chronic hepatitis B and C, autoimmune hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease [1].Hepatitis C virus in Egypt is the most common cause of chronic liver disease (CLD). The disease severity ranges from mild illness to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) which are the most common causes of death in patients with (CLD). Chronic liver injury of virtually any etiology triggers inflammatory and wound-healing responses that in the long run promote the development of hepatic fibrosis and HCC [2].The innate immune system detects HCV and responds to its stimuli, mainly through recognition of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) Activation of TLRs leads to a series of signaling events resulting in the production of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, and other TLR-induced inflammatory cytokines [3]. The human TLRs can be divided into five subfamilies: TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR9. Among them, the TLR2 subfamily consists of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and TLR10, and the TLR9 subfamily is composed of TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9. The TLR3, TLR4, and TLR5 families are only represented by one member each [4]. The TLRs can identify HBV, HCV, and other pathogenic microorganisms, and play an important role in the anti-inflammatory and anti-viral response via two major signal transduction cascades: the MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways, they can identify viral genomes with high CpG (cytosine-phosphate-guanine) DNA content, dsRNA, and PAMPs, so that acquired immunity is activated and produce multiple cytokines and up regulating the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86) [1].TLR3 is expressed on parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells in the liver as well as in many types of immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, NKT cells, and so forth [5].Activation of NK cells by the TLR3 ligand poly I:C inhibits liver fibrosis via killing of activated stellate cells and producing IFN- that subsequently induces stellate cell apoptosis and inhibits stellate cell proliferation. Clinical studies suggest that TLR3 may contribute to the resistance to HCV subtype Ia infection but seems to have no role in disease progression after a chronic infection is established [6].Type I IFN induces the maturation of dendretic cells (DCs) by increasing both the expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86, and CD40 and antigen presentation via major histocompatibility complex class I in addition to classical endogenous antigen presentation; it also facilitates the cross-presentation of viral antigens. A cumulative report has shown that DC activation via TLR signaling is a prerequisite for the subsequent induction of vigorous T-cell responses [7].At the cellular and molecular level, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that TLR3 plays a role in cirrhosis pathogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis For example, it has been documented that dsRNA activates TLR3 which subsequently results in NK cell accumulation and activation leading to inflammation of the liver. Such process could contribute to cirrhosis and HCC if left untreated. Previous studies using a rat model showed that activated TLR3 could inhibit HCC development [8].

2. Aim of the Work

- The aim of this work is to determine the serum levels of IFN-α, TLR3 expression in Egyptian patients with liver cirrhosis as well as their correlation to other -biochemical parameters.

3. Subjects and Methods

- This study included 60 patients divided into 2 groups; group A: comprised 30 patients with pure HCV infection without cirrhosis, group B: comprised 30 patients with liver cirrhosis due to HCV infection together with 30 healthy control referred to Tropical Medicine Department, Al-zahraa University Hospital, informed consents was obtained from all the patients and controls. The diagnosis was established on the basis of history, clinical, laboratory, abdominal ultrasound. CBC, ESR, liver, kidney function tests, HBS antigen & anti-HCV antibody, interferon α and TLR3expression were also done. Inclusion Criteria: Adult patients (>18 years), both sexes (males or females) and patients with CHCV infection. Exclusion Criteria: Patients who had received antiviral treatment, patients with HIV or HBV co-infections and patients with HCC.Methods: All patients and controls was subjected to the following: Full history taking. Complete clinical examinations, Abdominal Ultrasound, liver biopsy was done for some cases when indicated.Laboratory investigations: Blood samples were collected from the patients at the time of diagnosis, before any kind of treatment (surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy) as well as from the control group. Each blood sample was divided into three portions as follows:- First portion was collected into Na citrate-containing tube, and used for estimation of prothrombin time (PT) immediately on automated blood coagulation analyser (stago) and for ESR estimation by Westergren’s method. - The second portion was collected into EDITA containing tube for CBC estimation using Coulter Counter T890 (Coulter LH 750 analyzer, Berlin, Germany).- The third portion was put in a plain tube, left to clot then centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 20minutes and ---serum was separated and used for estimation of: - Liver and kidney function tests were done on Hitachi 911 auto-analyzer (Roche-Hitachi, Japan). - Detection of HBS antigen & anti-HCV antibody by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), - The presence of HCV RNAby reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). - Serum Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) was detected by COBAS e411 chemiluminescence auto analyzer using Roche reagents (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, D-68289 Mannheim, Germany).- Estimation of interferon α by ELISA kit (Verikine Human IFN Alpha supplied from pbl assay Science catalog NO4110) with extended range 156-5000 pg/ml .this kit quatitates the human interferon alpha in the media using a sandwich immunoassay. The kit is based on ELISA with anti detection antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Tetra methyl-benzidine (TMB) is substrate. The assay is based on international reference standard for human interferon alpha provided by national institute of health- Determination of relative level of TLR3expression by real time PCR. Gene Expression Analysis Real time PCR amplification was done by Rotor - Gene Q Real Time PCR instruments from QIAGEN USA. Using real-time PCR kit (Lot Number 1091352 Rev. E APPLIED BIOSYSTEMS. 03/2017). Total RNA was extracted from peripheral venous blood of each individual using RNA extraction and purification kit (QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit, Qiagen, Germany) in fully automated on the QIAcube (Germany). Isolated total RNA was quantified photo spectrometrically at 260 nm. Purity of total RNA was assessed by the 260/280 nm ratio which was between 1.8 and 2.1. The RNA integrity was tested on the Nano drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Germany) which is a full spectrum (220 -750nm) spectrophotometer that measures 1 μl samples with high accuracy and reproducibility. Immediately after blood drawing with the RNEASY Blood RNA system (Quiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany). The mRNA was transcribed into cDNA, using the Omniscript reverse transcription kit (Quiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany).- QIAGEN's real-time PCR cycler (Rotor-Gene Q, USA) was used to determine the cortex DNA copy number. PCR reactions were set up in 25 μL reaction mixtures containing 12.5 μL 1× SYBR® Premix ExTaqTM (TaKaRa, Biotech. Co. Ltd.), 0.5 μL 0.2 μM sense primer, 0.5 μL 0.2 μM antisense primer, 6.5 μL distilled water, and 5 μL of cDNA template. The reaction program was allocated to 3 steps. First step was at 95.0°C for 3 min. Second step consisted of 40 cycles in which each cycle divided to 3 steps: (a) at 95.0°C for 15 sec; (b) at 55.0°C for 30 sec; and (c) at 72.0°C for 30 sec. The third step consisted of 71 cycles which started at 60.0°C and then increased about 0.5°C every 10 sec up to 95.0°C. The fluorescence products were differentiated by ABI sequencer 377 (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of specific primer of the TLR 3 are forward primer TGGTTGGGCCACCTAGAAGTA and reverse primer: TCTCCATTCCTGGCCTGTG.

4. Statistical Analysis

- Data were collected, reviewed and fed to the computer where statistical analysis was done using the Statistic Package for Social Science Version 17 (SPSS 17.0) for windows. Comparing groups was done using Student's t-test and f-test. Study of the relationship between variables was done using correlation coefficient (Pearson correlation). The level of significance was taken at P-value of <0.05" and high significant at P-value of < 0.001.

5. Results

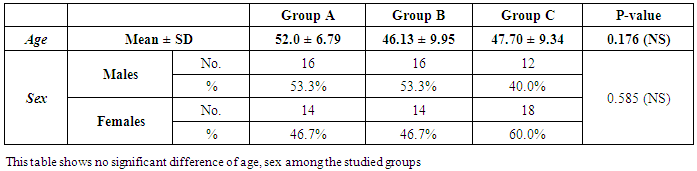

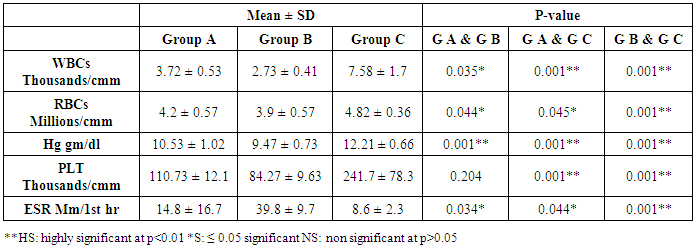

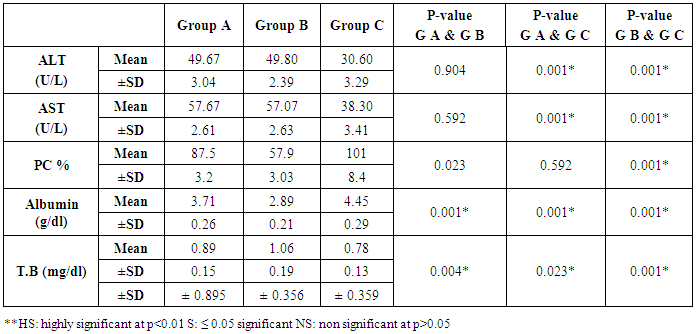

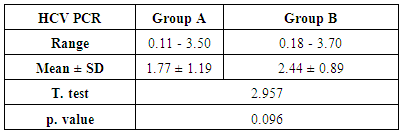

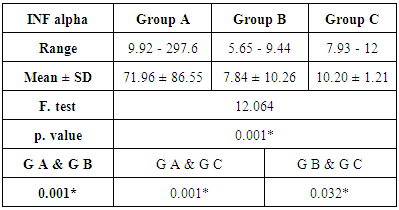

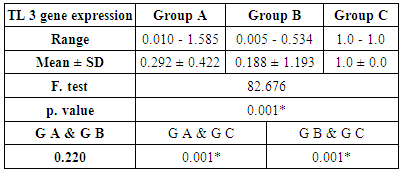

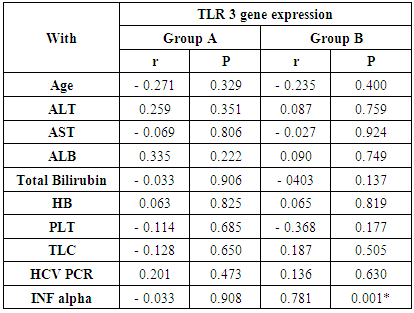

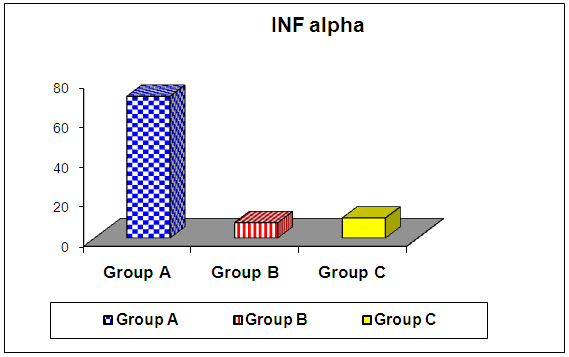

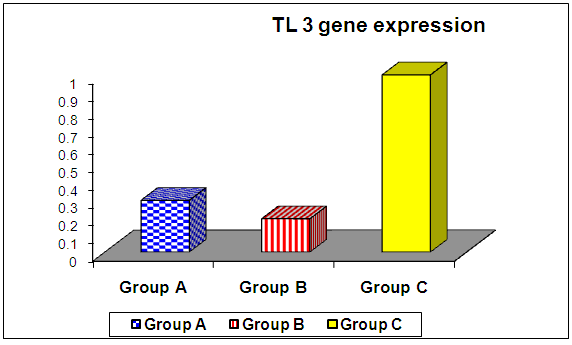

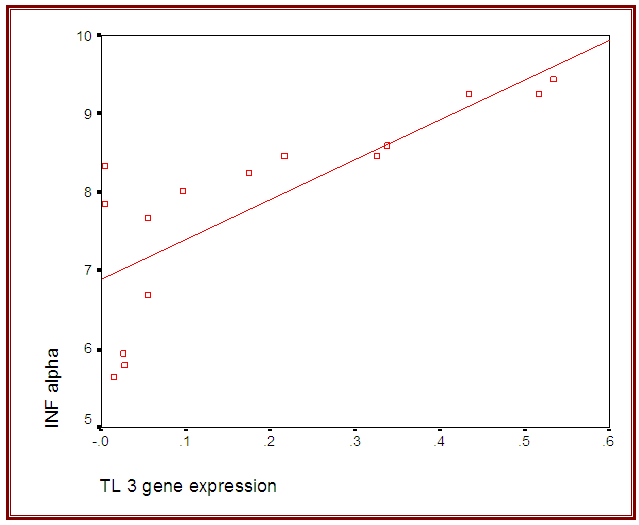

- The current study included 90 subjects (60 patients 32(53.3%) males & 28 (46.7%) females, their ages ranged from 25 to 75 years. and 30 healthy subjects as a control group. The results and data were collected and analyzed in tables 1-8 and figures 1-3.As regard serum INF alpha levels there was highly significant increase in group (A) (mean = 71.96 ±86.55), as compared to group (B) (mean = 7.84±10.26), also by comparing group (A) to group(C) mean = 10.20 ± 1.21) there was significant difference, and when we compared (B) to group(C) there was significant difference (P<0.05) {Table (5) and Fig. (1)}.There was no significant difference as regard TLR 3 gene expression by comparing group (A) and group (B), while by comparing group (A), and (B) with group (C) there was highly significant difference {Table (6) and Fig. (2)}. There was significant positive correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (B), while there was no significant correlation between TL 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (A) also there was no significant correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and (Age, ALT, AST, ALB, Total Bilirubin, HB, PLT, TLC and presence of HCV by PCR) neither in group (A) nor in group (B) {Table (7) and Fig. (3)}.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure (1). Comparison of serum INF alpha among the studied groups |

| Figure (2). Comparison of TLR 3 gene expression among the studied groups |

| Figure (3). Correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (B) |

6. Discussion

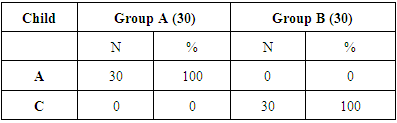

- Liver cirrhosis is characterized by a progressive replacement of the functional hepatic architecture by non-functional fibrotic tissue. Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C virus infection are the two main etiologies of chronic liver diseases leading to cirrhosis and liver-related death in the Western world. While the overall death rate caused by cirrhosis has fallen in the last thirty years, HCV death rates, closely associated with cirrhosis, have been increasing since the 1990s [9]. Hepatitis C affects approximately 3.2 million people within the United States and 170 million people worldwide. About 30% of patients chronically infected with Hepatitis C virus (HCV) show signs of active hepatic inflammation, and are at risk of developing fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [10, 11]. Hepatitis C is a significant public health problem in Egypt where the highest prevalence (14.7%) of hepatitis C virus exists. Hepatitis C virus prevalence is even higher among clinical populations and groups at risk of exposure to infection [2].Toll-like receptors play an important role in the wound healing and regeneration processes in the liver but they are also involved in the pathogenesis and progression of various inflammatory liver diseases as including autoimmune liver disease as fibrogenesis, and chronic HBV and HCV infection [12].Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) is a major intracellular receptor that recognizes viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and initiates inflammatory responses against deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Therefore, TLR3 plays an important role in the immune response to infections caused by such viruses and might influence the chronicity of such viruses, eventually leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Furthermore, polymorphisms in the TLR 3 gene have been associated with susceptibility to or the clinical progression of infection [13, 14].The aim of this work was to determine the serum levels of IFN-α, TLR3 expression in Egyptian patients with liver cirrhosis as well as their correlation to other -biochemical parameters. The results of this work revealed that expression level of TLR3 was down regulated in both patient groups as compared to normal healthy subjects. These results are in agreement with those of Motavaf et al., (2014) [15] study, in which the levels of TLR3 and TLR7 expression was reported to be significantly down regulated in patients with chronic HCV infection when compared with healthy controls. The results of a study conducted by Firdaus et al., (2014) [14] indicated that expression of TLR 3 mRNA in HCV patients induced cirrhosis of liver showed more significant decrease than individuals who had spontaneously cleared the viral infection.Mohammed et al., (2013) [16] also supported our findings. However, this results opposed with those published by Dolganiuc et al., (2006) [17], who reported upregulation of almost all TLRs (including TLR3 and TLR7) in monocytes and lymphocytes of patients with chronic HCV infection This contradiction can be explained by a number of factors including difference in methodological approaches (cellular separation vs. total blood) and differences in clinical stage (non of the patients included in that work had cirrhosis at the time of study, but from the group of patients in our study, 30 had cirrhosis).The present study showed that level of INF-α was significantly higher in group (A) patients as compared to control group and was significantly lower when group (B) was compared to control group.These results were coordinated with Abdel-Raouf et al., (2014) [18] who demonstrated that expression of viral NS5A protein inhibits the signaling pathway of TLR2, TLR4, TLR7 and TLR9 by binding to the adaptor protein MyD88 and inhibiting the recruitment of IRAK4 leading to a decrease in MyD88-dependent signals responsible for IFN-α production. Domanski et al., (1996) [19] explained this finding, that IFN- α genes have a regulatory domain within the virus-response element that determines cell-specific gene expression. Thus, it can be thought that interaction of HCV with different cell transcription factors in PBMC and in the liver can arbitrate the opposite changes in IFN-α gene expression found in these two tissues in chronic HCV infection.Our studies showed that there was significant correlation between TL 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (B), These results were coordinated with Mohammed et al., (2013) [16] who reported that expression levels of TLR3 is strongly correlated with the expression level of IFN-α. The same results were obtained by Lin et al., (2013) [20] who suggested that one of the mechanisms leading to the chronicity of infection could be the acquisition of an ‘‘exhausted’’ state of this antiviral machinery at the late stages of infection. This goes with the result of Atencia et al., (2007) [21] who reported that the expression levels of TLR3 and TLR7 correlate strongly with the expression level of IFN-α, suggesting that this down-regulation appears to be related with the infection, as the same analysis performed on patients with liver cirrhosis not related with viral infections (mainly of alcoholic origin) did not show significant differences when compared with healthy controls. Reduced expression of TLR3 on innate immune cells with subsequent decrease in IFN-α production suggests that new therapies that aim to increase the expression level of TLRs or their activity may help in treatment of HCV infection. Synthetic activators of certain TLRs induce type I IFNs, which are known to inhibit HCV replication. TLR stimulation can also exert an IFN-independent antiviral effect (Motavaf et al., 2014) [15].We found no significant correlation between TL 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (A) also there was no significant correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and (Age, ALT, AST, ALB, Total Bilirubin, HB, PLT, TLC and viral load) this is in agreement with Mohammed et al., (2013) [22] while there was significant positive correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in group (B) in contrast to Mohammed et al. (2013) [16] this can be explained as group (B) patients in our study were (cirrhotic patients Child C) while their patients group were compensated Child A CHCVHepatitis C therapy IFN therapy involves the administration of a single IFN- subtype (2a or 2b), TLR activation induces a range of different IFN subtypes. For example, the TLR7 agonist imiquimod has been shown to induce IFN- 1, - 2, - 5, - 6, and - 8. This could offer improved antiviral efficacy, since different IFN subtypes have been shown to have different antiviral potencies against HCV, and some subtypes have synergistic activities in combination with others. It is also possible that different subtypes could have differences in side effects [22].New Direct Acting Antiviral Agents (DAAs) are efficacious and safe for both compensated and decompensated hepatitis C related chronic liver disease. More and more trials will further improve the outcome of the disease. Furthermore, the effect of these DAAs is yet to be analysed for eastern populations. It is expected that these agents will altogether change the spectrum of hepatitis C related diseases in near future [23].In conclusion: The results of this study suggested that Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) is likely involved in early pathogen detection and the host response to HCV infection as well as in liver cirrhosis. There is significant positive correlation between TLR 3 gene expression and INF alpha level in cirrhotic patients due to CHCV infection. The down regulation of TLR3 expression by HCV may contribute to the decrease of IFN-α in chronic HCV and cirrhotic patients.

7. Recommendations

- Ÿ Further studies are needed to detect the possibility of targeting this receptor to enhance the immune response and clear the infection. Ÿ A greater understanding of the specific cellular source of TLR signals and TLR pathway changes in different stages of viral infection may assist in the design of appropriate therapeutic interventions that target these receptors in patients with CHCV infection. Ÿ Further studies on large scale to determine the serum levels of IFN-α, TLR3 expression in Egyptian patients with liver cirrhosis before and after new oral DAAS.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML