-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Biochemistry

p-ISSN: 2163-3010 e-ISSN: 2163-3029

2016; 6(5): 122-129

doi:10.5923/j.ajb.20160605.02

New Biomarkers for Response to Treatment of HCV Infected Patients Based on IP-10 and IL 28B Polymorphism Analysis

Ahmed Mostafa Aref 1, Mohamed Shamrouh Othman 2, 3, Samah Mamdouh 4, Ehab Dabaa 4, Moataz Hassanein 5, Mohamed Ali Saber 4

1Biological Science Department, October University for Modern Sciences and Arts, Egypt

2Preparatory Year College, Hail University, Hail, KSA

3Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Faculty of Biotechnology, October University for Modern Sciences and Arts, Egypt

4Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Giza, Egypt

5Hepatogastrointerology Department Theodore Bilharz Research Institute, Giza, Egypt

Correspondence to: Ahmed Mostafa Aref , Biological Science Department, October University for Modern Sciences and Arts, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)rs12979860 near IL28B gene was shown to be highly predictive of sustained virological response (SVR) in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Inducible protein 10 (IP-10) in CHC patients increases in non-responders. To assess the potential predictive value of pretreatment IP-10 levels and IL28 B genotype on the SVR in CHC Egyptian patients, eighty-seven patients were included in this study in addition to twenty control subjects. HCV viral load levels were assessed at 0, 12, 24, 48 and 72 weeks, IL28B single nucleotide polymorphism rs1297860 was genotyped and serum IP-10 level were evaluated for each patient. Results have shown that the distribution of SNP was CC (28.1%), CT (43.6%) and TT (28.1%) with SVR 70%, 38.7%, 50% respectively, at cutoff value 342pg/ml for predicting SVR we achieved a sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 46%, respectively. In conclusion, pretreatment serum IP-10 level when added to IL28 genotype, the predictive value is greatly enhanced especially for CT and TT IL28 genotypes.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis C, IP-10, IL28 polymorphism, Interferon, Ribavirin

Cite this paper: Ahmed Mostafa Aref , Mohamed Shamrouh Othman , Samah Mamdouh , Ehab Dabaa , Moataz Hassanein , Mohamed Ali Saber , New Biomarkers for Response to Treatment of HCV Infected Patients Based on IP-10 and IL 28B Polymorphism Analysis, American Journal of Biochemistry, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 122-129. doi: 10.5923/j.ajb.20160605.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Hepatitis C is a global health problem. There were 120–180 million hepatitis C virus (HCV) carriers world-wide, with worldwide prevalence estimated at 3% [1]. Egypt has the highest prevalence in the world, with an estimated >500,000 new infections annually making Egypt the highest endemic country [2] with predominance of subtype 4a [3, 4]. Standard treatment of CHC with Pegylated interferon α-2a (peg-IFN α-2a) and ribavirin results in sustained virological response (SVR) rates of less than 50% in HCV genotype 1 or 4 infected patients, contrasted by SVR rates of 70–90% in HCV genotype 2 and 3 patients [5]. This treatment is not only long and costly, but also there are serious side effects (e.g., GIT symptoms, hematologic abnormalities and adverse neuropsychiatric events) [6].CXCL10 (also known as IFN-γ–induced protein–10, or IP-10), an IFN- and TNF-α–inducible chemokine that can be highly expressed by endothelial cells, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, mesangial cells, astrocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and hepatocytes [7]. Many studies reported that patients with CHC have high systemic levels of IP-10 and the base line levels of IP-10 are higher in patients who don't achieve SVR compared with patients with treatment-induced resolution of HCV infection in HCV genotype 1 patients. These studies suggested that IP-10 not only has a pretreatment predictive value in CHC but can also predict rapid virological response (RVR) [8, 9].Genome-wide association studies(GWAS), have shown that host genetic factor in the form of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)near the IL28B gene can predict spontaneous and treatment induced viral clearance in HCV genotype 1 [10, 11]. The mechanisms, how this polymorphisms affect antiviral host responses have remained elusive. We aimed to evaluate the predictive power of the rs12979860 IL28B SNP and pretreatment IP-10 levels on the sustained viral response in HCV Egyptian chronic patients whom underwent peg-IFN α-2a /ribavirin (800–1200 mg) therapy for 48 weeks.

2. Patients and Methods

- One hundred and seven individuals were included in this study. All patients and controls gave their informed consent, which was ethically conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.Individuals under investigation were grouped into:Group 1: Normal control group, including 20 apparently healthy volunteer with no evidence of liver disease.Group 2: CHC group, including 87 patients positive for both HCV-Ab and HCV RT-PCR and negative for HBsAg and anti-HBc.Ten milliliters of fasted venous blood were taken from patients and controls, the blood was left to clot. Serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at -80°C until further examinations.

2.1. HCV-RNA Quantification

- HCV-RNA viremia was quantified by the Abbott Real Time HCVm2000 assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, Illinois, USA) using ABI Prism 7500 for detection. HCV-RNA levels were assessed at 0, 12, 24, 48 and 72 weeks. The lower detection limit is 12IU/ml. Patients were classified according to Ghany et al. [12] into:1) Early virological responders (EVR) if they achieve seronegativity of HCV RNA at 12 weeks of therapy.2) Sustained virological response (SVR) if serum HCV-RNA was un-detectable 24 weeks after completion of therapy.3) Non responder (NR) patients with reappearance of HCV RNA during therapy.

2.2. IP-10 Quantification

- Before starting of therapy, serum IP-10 level was measured in all groups by the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine® ELISA R & D Systems, Minneapolis, USA). The minimum detectable level is1.67 pg/mL.

2.3. Liver Histology

- Liver biopsies from all patients were read and scored. The Ishak score 18 according to [13] was used for grade of inflammation and necrosis (range 0–18 and for stage of fibrosis (range 0–6).

2.4. Genotyping of IL28B

- DNA samples from patients were genotyped for the IL28B polymorphic marker rs1297860 using the ABI TaqMan allelic discrimination kit and the ABI Prism 7500 (Applied BiosystemsInc, Foster City, CA USA), according to manufacturers recommended protocols Detection System (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan probes and primers were designed and synthesized by Applied Biosystems Inc. Automated allele calling was performed using SDS software fromApplied Biosystems Inc. Positive and negative controls were used ineach genotyping assay. The primers and probes utilized were:NCBI dbSNP ID rs12979860 Forward primer: TGTACTGAACCAGGGAGCTC, Reverse primer: GCGCGGAGTGCAATTCAAC, Vic probe: TGGTTCGCGCCTTC, FAMprobe: TGGTTCACGCCTTC.

2.5. Biochemical Investigations

- Serum levels of AST, ALT, ALP, albumin and Bilharzial antibody were measured for all subjects by the commercially available assays.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

- Serum IP-10 levels were correlated with SNP and the clincopathologic parameters including patients age, sex, viral load, liver histology (stage and grade) and Schistosomal infection.Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0. The following tests were used: Chi-square test

, Spearman correlation and calculation of the mean value, the probability value (P) was expressed as following: P-value > 0.05: non-significant, P-value ≤ 0.05: significant, P-Value < 0.01: highly significant. Sensitivity, specificity, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and area under the curve (AUC) were carried out using MedCalc (Mariakerke, Belgium) software.

, Spearman correlation and calculation of the mean value, the probability value (P) was expressed as following: P-value > 0.05: non-significant, P-value ≤ 0.05: significant, P-Value < 0.01: highly significant. Sensitivity, specificity, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and area under the curve (AUC) were carried out using MedCalc (Mariakerke, Belgium) software.3. Results

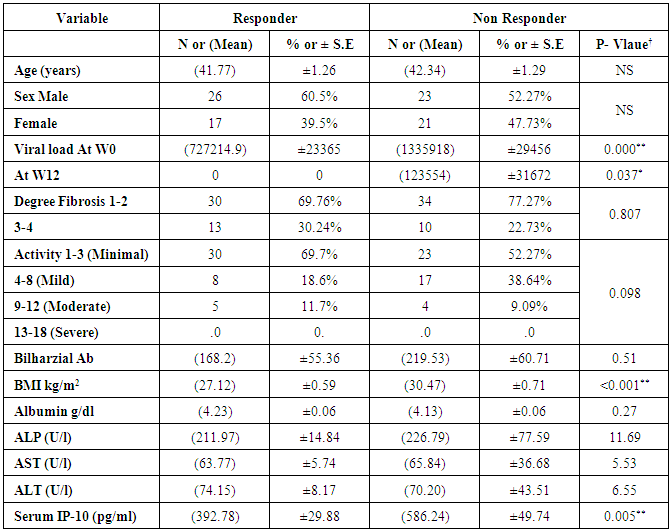

- AS shown in Table (1) from eighty-seven patients enrolled in this study, 43 patients have shown SVR (49.4%) with mean age 41.7 years (y) while 44 patients (50.6%) were not responders with a mean age 42.34y. Mean body mass index (BMI) for responders was 27.12kg/m2 while it was 30.47kg/m2 for NR.We didn't achieve any significance difference in baseline parameters including AST, ALT, ALP, albumin and Bilharzial Ab between patients who achieved SVR and NR, while there was a statistical difference regarding viral load at baseline (W0) and BMI as shown in table 1.

|

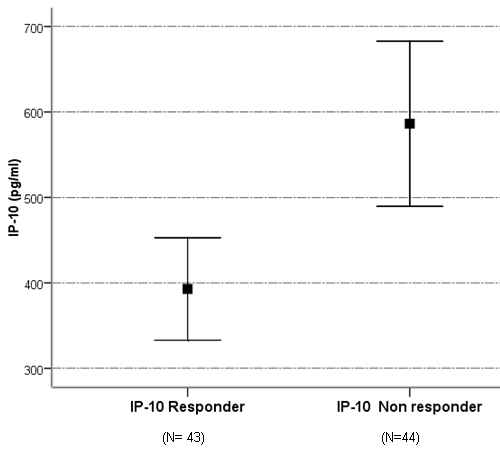

3.1. IP- 10 Serum Levels

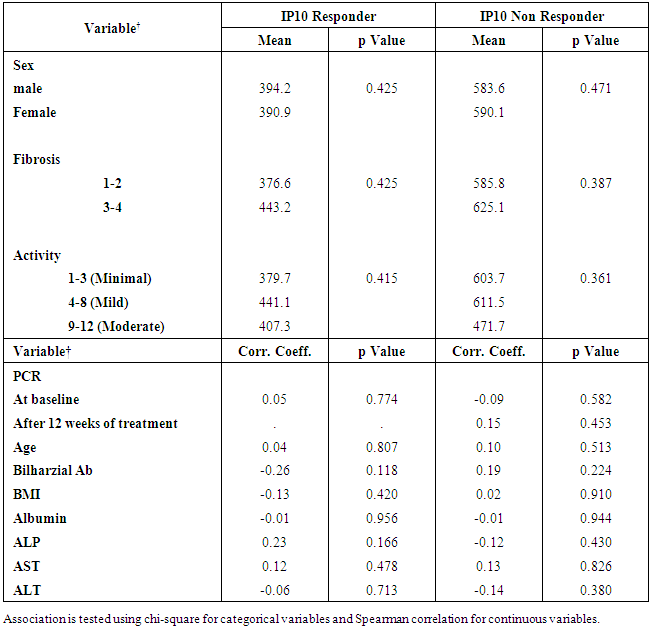

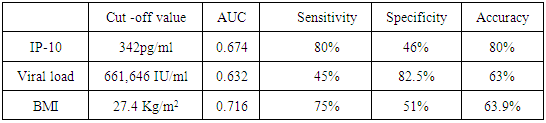

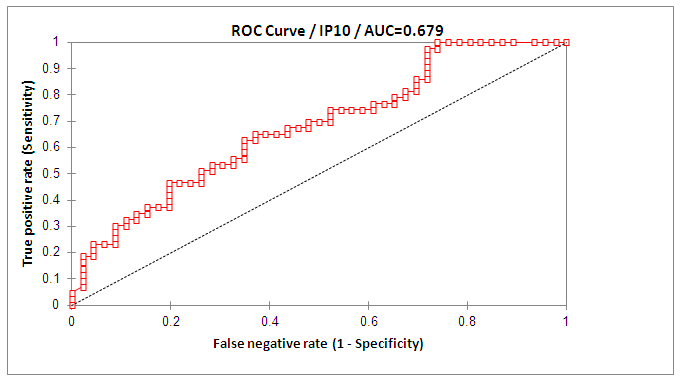

- The mean serum levels of IP-10 were significantly higher in CHC patients (493.91 ± 28.60) pg/ml than NC group (90.97±8.62), (p< 0.001). At the same time the mean serum levels of IP-10 were significantly elevated in NR group (586.24± 49.74) compared with SVR group (392.78±29.88), p<0.05, (Table 1, Fig 1).The ROC curve of IP-10 showed an AUC of 0.679 (95% confidence interval 0.56–0.78). At a cutoff value 342pg/ml for predicting SVR, at this point the sensitivity and specificity were 80% and 46%, respectively with a positive predictive value and a negative predictive value of 69% and 61%, respectively (Fig. 2, Table 3).There was no significant association between IP-10 and clincopathologic parameters such as age, sex, viral load at (W0, W12), grade of inflammation, stage, BMI, albumin, AST, ALT, ALP and Bilharzial infection in SVR and NR patients as shown in table 2.

| Figure 1. Serum level of IP-10 in SVR and NR patients |

|

| Figure 2. ROC curve of IP-10 for discrimination of SVR from NR patients |

|

3.2. HCV Viral Load Results

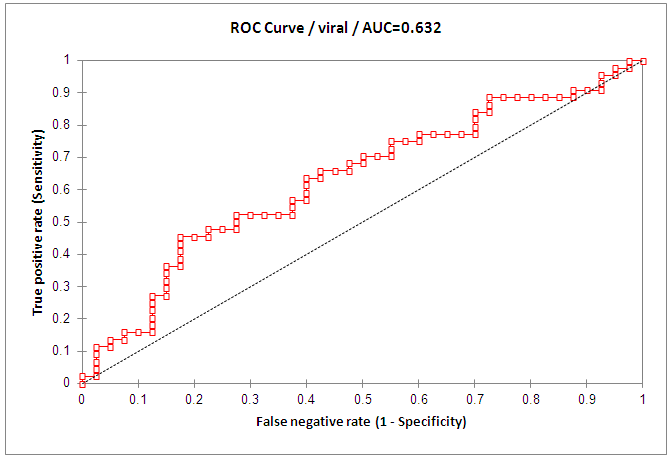

- At base line the mean value for HCV viral load was 727, 214 IU/ml in responders while in non-responder patients it was 1,335,918 IU/ml, with statistical significance between the responders and non-responder patients (p < 0.05) (Table 1). At week 12 (EVR), HCV-RNA serum level was undetectable in all the responder patients, with statistical significance when compared with NR group (p <0.05).Figure 3 and table 3, showed that the AUROC for viral load was 0.632, with a sensitivity of 45%, specificity 82.5%, accuracy 63.9% and optimal cutoff value 661,646 IU/ml.

3.3. BMI Results

- Table (1) showed a significant decrease in the BMI in SVR compared with NR group (p<0.05).

| Figure 3. ROC curve of viral load for discrimination of SVR from NR patients |

3.4. Histopathological Results

- Early fibrosis stage (score 1-2) was found in 30 (69.7%) of responders versus 34(77.3%) of NR, higher stage (score 3-4) was found in 13(30.2%) of responders and 10(22.7%) of NR patients. In addition the results of this study did not show any statistical significance comparing the grade of necroinflammatory activity withIP-10 even after stratification to minimal, mild and moderate.

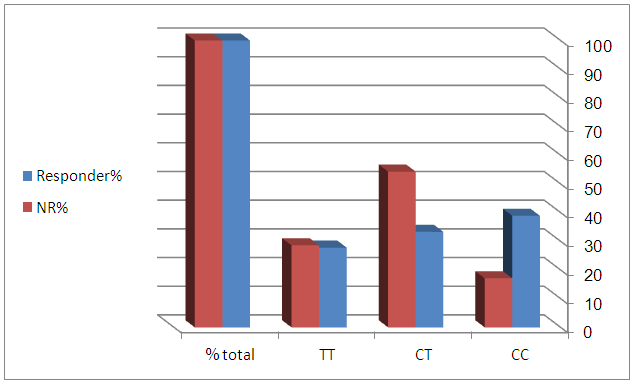

3.5. IL28B Genotype and Treatment Response

- The distribution of SNP of IL28 genotypes was CC (28.1%), CT (43.6%) and TT (28.1%) with SVR 70%, 38.7%, 50% respectively as shown in figure (4). There was a significant difference when comparing the CC genotype between SVR and NR patients (p< 0.05), but not with CT or TT. Using spearman correlation there was no significance correlation when comparing the genotype with the viral load and IP-10, which indicates that they are independent factors.

| Figure 4. IL28b SNPs genotypes distribution in responder and non responder patients groups |

4. Discussion

- IP-10 is a CXC chemokine that targets T lymphocytes and monocytes, the serum level of IP-10 in CHC patients are higher than healthy controls , rheumatoid arthritis patients and even those infected with HBV patients , these results indicate that IP-10 have a role in the pathogenesis of HCV infection [14-16]. IP-10 is proposed as a predictor factor for SVR for CHC genotype 1 patients pretreatment with interferon and ribavirin [17-19], while only few reports have dealt with genotype 4 [20].Recently, several reports on a gene polymorphism (rs12979860) upstream of IL28B are favorably associated with treatment response to peg-IFN and ribavirin [21-23]. Carriage of the C allele increases treatment response rates with those who have the CC genotype having the highest SVR rates, CT intermediate and TT have the lowest response [21].In the current study, we tried to combine the IL28B genotype with baseline IP-10 levels and viral load to demonstrate an independent and additive model for predicting SVR for CHC Egyptian patients treated with the combined peg-IFN and ribavirin.The main finding of the present study is the significant association of serum IP-10 levels in NR compared to SVR in CHC patients whom underwent peg-IFN- α plus ribavirin therapy showing higher serumIP-10 levels in NR patients compared to SVR patients, 586 and 392pg/ml respectively.Depending on the ROC curveresultsofIP-10, at cutoff value 342 pg/ml the best sensitivity and specificity were 80% and 46%, respectively, which could have a discriminating power to differentiate SVR from NR patients. Results also revealed that 37 (84%) NR patients have higher IP-10 than 342pg/ml. these results are inconsistent with many other reports which have shown that baseline IP-10 is lower in SVR patients compared to NR [17, 19, 24, 25].Our proposed cutoff value is different from that obtained by [18, 19] who have proposed cutoff values at594 pg/ml and 600pg/ml respectively, to identify genotype1 HCV responders from non-responders. This higher cutoff value may be due genotype difference, because the predominant subtype in Egypt is 4a [3, 4].It is unclear why high IP-10 levels are associated with poor response to HCV therapy. The IP-10 receptor (CXCR3) is upregulated on lymphocytes in chronic HCV and hepatocytes appear to be the predominant source of IP-10 in chronic infection [26-28]. While intrahepatic IP-10 levels correlate with necroinflammatory changes and fibrosis in HCV, its role in viral clearance is less clear. Low pretreatment IP-10 levels are associated with a rapid decline in HCV viral load during the first 24–48 hours of interferon therapy [17]. Patients with low baseline levels of interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) expression appear to have a more robust response to exogenous peg-IFN and a higher SVR rate. In contrast, those with high baseline ISG expression appear to be refractory to further IFN signaling [27, 29]. High IP-10 levels may be a marker of this refractory state, or excess IP-10 may directly interfere with critical signaling pathways.Casrouge et al. assumed the presence of antagonist form of IP-10, this dominant negative form of the protein, is capable of binding CXCR3 but does not induce signaling, so no cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) migration to the liver, this postulation may support our results regarding the absence of significant association between IP-10 and histopathologic results but this needs further investigations [30].At base line (W0), there was a significant difference in the viral load between the responders and non-responders (P<0.05). These results are in accordance with other reports that have shown that low viral load is an independent favorable factor for the treatment outcome [24, 31-34]. Our results indicated that 40.9% (18 / 44) of NR patients showed EVR, this means that 29.5% of all EVR patients were relapsed (18 / 61), while 70.5% of CHC patients who showing EVR achieved SVR Indicating that EVR is a strong predictor of the treatment outcome.We have observed that 72.2% of the relapsed patients (13 /18) have serum level of IP-10 above the proposed cutoff value at base line. There wasn't any correlation betweenIP-10 pretreatment level and viral load at base line and SVR, these results are in accordance with Diago et al. [18] while it was in contrast with Reiberger et al. [24]. Although the serum level of IP-10 is higher in advanced stages of fibrosis, there is no significant correlation betweenIP-10 and fibrosis. our results are not in accordance with other reports [19, 24, 35, 36] who have shown association between IP-10 and fibrosis in genotype 1 CHC patients and this difference in results may be due dual infection with HIV/HCV [35]. Our finding showed the absence of association of IP-10 and the liver enzymes; AST and ALT. These enzymes are known to be related to the degree of liver damage.The distribution of IL28 genotype showed that CT is the most frequent genotype (43.6%) followed by CC and TT with almost the same frequency (28.1%). The CC genotype was significantly correlated with SVR in comparison to CT and CC genotypes our results are in consistent with many other reports [22, 23, 37].In the current study, although the CC genotype have shown the highest SVR (70%), unexpectedly we found that SVR within TT genotype was higher than CT genotype 50% and 38.7%, respectively, which is not in agreement with concept that the T allele is associated with treatment failure. so we believe that the SNP genotype is no the only factor which is associated with treatment failure.Combining baseline IP-10 levels with the IL28B rs1297860 genotype provided additional and independent information specifically, with those CT and TT carriers. The overall response rate for CT carriers was only 38.7%, but when we stratified them according IP-10 cutoff value we found that those with IP-10 levels below 342pg/ml had 61% SVR versus 22% with high IP-10 levels.For the TT genotype, it showed 50% overall response, with no responders in those whom have IP-10 above the cutoff value while those with low pretreatment IP-10 had 40% SVR. Our results supports the results of Darling et al. who have shown that the additive value of IP-10 serum levels were most pronounced for those CT and TT carriers [23]. Our results also revealed that there was no any significant correlation between the pretreatment serum levels of IP-10 and IL28 genotypes, indicating that they are independent factors.

5. Conclusions

- Predicting response to antiviral therapy is a crucial point in the management of patients with CHC. There is high proportion of Egyptian patients who still do not respond to interferon/ribavirin therapy, so searching for predictive factors in these groups of difficult-to-cure patients is needed. Here we provide evidence that pre-treatment screening of IL28B genetic variants, together with measurement of IP-10 may provide useful information prior to initiating peg-interferon therapy for CHC Egyptian patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This research work was funded by Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF) of Egypt project ID# 1763 (TC/2 Health). We are thankful to Dr. Huda Abo Taleb for her kind assistance in performing statistics.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML