-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Biochemistry

p-ISSN: 2163-3010 e-ISSN: 2163-3029

2016; 6(2): 30-36

doi:10.5923/j.ajb.20160602.02

Increased Production of CEA and CA19-9 in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Abdel Hamead A. F. Mohammed1, Ali S. Mohammed1, Samar Mansour2, Abdelhafeez Moshrif3, Farahat M. Z.1

1Clinical Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Asyut, Egypt

2Clinical Pathology Department, South Egypt Cancer Institute, Asyut University, Asyut, Egypt

3Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Asyut, Egypt

Correspondence to: Abdel Hamead A. F. Mohammed, Clinical Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Asyut, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the production of a wide range of autoantibodies, with diverse specificities as a result of abnormal activation of auto-reactive B and T lymphocytes. Although the pathogenesis of the disease is largely unknown, both genetic and environmental factors are involved in this disease. The hallmark characteristics of SLE, including the production of autoantibodies, deposition of immune complexes in tissues and excessive complement activation, are generally thought to be consequences of immune dysregulation. Tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) are not only expressed on tumor cells like cancer colon, pancreas, stomach, ovary and breast but also may expressed in inflammatory conditions. The production of some TAAs may be increased in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc), SLE and other connective tissue diseases. CEA and CA19-9 contain sialylated carbohydrate motifs and they are involved in tumor-associated cell adhesion and metastasis. They are also produced by granulocytes and may have a role in inflammation and pathogenesis of SLE. Therefore this study aimed to assess the role of CEA and CA19-9 in SLE patients' pathogenesis, disease activity and clinical manifestations. Patients and methods: This study included 50 patients with SLE. They were 25 in activity and 25 in remission using standard ACR criteria. 25 age and sex-matched healthy control group was also included. The values of CEA and CA19-9 in all patients and control were assessed. Results: There was significant increase of CEA concentration in activity compared to remission and control groups (4.38 ± 2.62 vs. 3.05 ± 1.93 and 2.72 ± 1.68 respectively) p<0.05. But there was no significance increase in remission versus control groups (3.05 ± 1.93 vs. 2.72 ± 1.68) p>0.5. CA19-9 concentrations were significantly higher in activity compared to remission and control groups (29.74 ± 21.15 vs 16.29 ± 9.99 and 12.74±7.72 respectively) p<0.01, but there was no significance increase in remission compared to control group (P > 0.1). 20% CEA cases were positive (≥7 U/ml) in activity group, 12% in clinical remission and 8% in control groups, Positive cases ≥ 37 ng/ml for CA19-9 were 24% in activity, 4% in remission and 4% in control groups. There were significant positive correlations between CEA and CA19-9 concentration in active SLE patients. Conclusions: CEA and CA19-9 are carbohydrate antigens, they have adhesive properties and increased production in SLE. They may have consequences for pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and the assessment of disease activity in SLE.

Keywords: SLE, CEA, CA 19-9

Cite this paper: Abdel Hamead A. F. Mohammed, Ali S. Mohammed, Samar Mansour, Abdelhafeez Moshrif, Farahat M. Z., Increased Production of CEA and CA19-9 in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, American Journal of Biochemistry, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 30-36. doi: 10.5923/j.ajb.20160602.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- SLE is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease. It is characterized by the production of a wide range of autoantibodies with diverse specificities as a result of abnormal activation of auto-reactive B and T lymphocytes [1]. Although the pathogenesis of the disease is largely unknown, both genetic and environmental factors are involved in this disease [2]. The hallmark characteristics of SLE are generally thought to be consequences of immune dysregulation [3].The surface of all human cells is characterized by a prominent sugar coat referred to as glycocalyx which is a glycoprotein polysaccharide covering. This surrounds the cell membranes of some bacteria, epithelia and other cells. Generally the carbohydrate portion of the glycolipids found on the surface of plasma membranes helps these molecules contribute to cell-cell recognition and adhesion [4]. The glycocalyx plays an important role in several cellular functions such as cell-cell communication, cell–matrix interaction or recognition of self and non-self [5].Tumor antigens (TAs) are a group of proteins expressed in tumors, and recognized by the host immune system. They represent markers that are either specific for individual tumors or generally over expressed in tumors as compared to normal tissues. TAAs are present on some tumor as well as normal cells [20].TAAs may 'apart from cancer cells', become expressed on the surface of inflammatory cells. These TAAs may play a role in the inflammation process, shed from cell surface and can be readily detected in the serum, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 [6]. CEA describes a set of highly related glycoproteins involved in cell adhesion. CEA is normally produced in gastrointestinal tissue during fetal development, but the production stops before birth. Therefore, CEA is usually present only at very low levels in the blood of healthy adults. CEA may be elevated in colorectal cancer, where it is most clinically useful indicator of the disease. However, it may also be elevated in a wide variety of other malignant conditions as breast cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer and cancer of esophagus. CEA also increases in non-malignant conditions as liver cirrhosis, chronic active hepatitis, autoimmune diseases, viral hepatitis and obstructive jaundice [7].Granulocytes express heavily glycosylated CEA-related glycoproteins (CD66 antigens). CD66b bears the selectin-binding carbohydrate structure, Lewis X, and mediates the adhesion to E-selectin, CD66b has also been considered as an activation marker on granulocytes [21].CA 19-9 is a tumor marker used for detection, follow up and prognoses of abdominal epithelial tumors especially pancreatic adenocarcinoma. High levels of serum CA 19-9 have been reported in non-malignant conditions as pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, cholestasis, liver cirrhosis and certain lung diseases [9]. A survey of serum CA 19-9 levels in autoimmune diseases revealed marked elevation in Sjogren's syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, dermatomyositis and SLE [10]. CA 19–9 acts as an E-selectin ligand, it contains carbohydrate determinants which involved in the adhesive properties of tumor cells and inflammatory leukocyte [22]. We aimed to evaluate the association of (CEA and CA19-9) in SLE and their possible role in the pathogenesis, disease activity and remission and systems involvement.

2. Patients and Methods

- This is across sectional study which was carried out at Al-Azhar University Asyut Hospital. Fifty SLE patients were enrolled in the study. They were divided into two groups, activity group and clinical remission group, each group included twenty five patients. All patients fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised criteria for classification of SLE [18]. Another twenty five age and sex-matched healthy persons were also included as control group. All of them were recruited from the outpatient clinics and inpatients of Rheumatology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Departments.Disease activity was measured by the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) [11, 18, 19]. Patients in clinical remission were chosen from follow up patients. They fulfilled the criteria of clinical remission adopted by Zen et al [17]. Patients with malignancy, current active or chronic infection, hepatitis or cholestasis were excluded from the study. An informed consent was taken from all patients and healthy controls before doing the study. The study was approved by Al-Azhar University Medical Ethics Committee.All groups were subjected to thorough history taking and clinical examination, with careful assessment of clinical signs, blood tests including: complete Blood Count (CBC) using (ABX Micros 60 hematology analyzer, France), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) using (Westergren method), complete urine analysis, liver function (ALT, AST, total protein and albumin) and kidney function tests (creatinine, urea and uric acid) were measured using Mindray BS380 clinical chemistry kits and analyzer. Creatinine clearance was estimated by Cockcroft-Gault Equation. C-reactive protein (CRP) and Rheumatoid factor (RF) were measured using Mindray BS380 Immuno- turbidimetric assay reagents. ANA by a quantitative ELISA kit (QUANTA Lite TM ANA, INOVA, USA). Quantitative measurement of human antibody to native ds-DNA was measured using ELISA kit (IgG anti-ds-DNA, DIA. PRO, Italy). Twenty four hours urinary proteins estimated by Stanbio total protein liquicolor (CSF/urine) kit, Texas, USA. The concentrations of CA 19-9 and CEA were measured by (ST AIA-Pack reagent using an AIA-360-Analyzer (Tosoh Bioscience, Tessenderlo, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ST-AIA-Pack assay is an automated monoclonal fluorometric assay. The serum samples were bound with monoclonal antibody that immobilized on a magnetic solid phase and enzyme-labeled monoclonal antibody in the AIA-PACK. The magnetic beads were then washed to remove unbound enzyme-labeled monoclonal antibody and were then incubated with a fluorogenic substrate, 4-methylumbel-liferyl phosphate (4MUP). The remaining enzyme activity on the solid phase (magnetic beads) was then measured using fluorescent rate method. The amount of enzyme-labeled monoclonal antibody that bound to the beads is directly proportional to the (CEA and CA19-9) concentration in the test sample. A standard curve was made and the unknown sample values were calculated using this curve. Assay results above 7 ng/ml for CEA and 37 U/ml for CA 19-9 were regarded as positive. In all positive samples, two repeats of the assay were performed and the mean was calculated.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS), Chicago, USA was used for data analysis. Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), number and percentage. Mean and SD were used as descriptive value for quantitative data. We used t test to determine significance of numeric variable when comparing two groups. Chi–square, ANOVA and post hoc were used to determine significance for non–parametric variable when comparing more than two groups. Pearson's correlation was applied for numeric variables in the same group. P > 0.05 considered as no significance and P < 0.05 for significant.

3. Results

- This study included fifty SLE patients, equally divided between activity and clinical remission groups. They were compared with each other and with twenty five healthy control group.

3.1. Elevated serum CEA and CA19-9 in SLE Patients

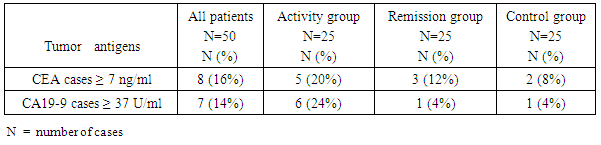

- When CEA concentrations were determined in sera of SLE patients and Controls, Significantly more SLE patients revealed abnormally high positive levels (values above the upper normal limit; "positive" patients) (20% of activity patients, 12% of clinical remission patients vs. 8% of control group), and for CA 19-9 (24%, 4% vs. 4% respectively) (p < 0.05) as in (Table 1).

|

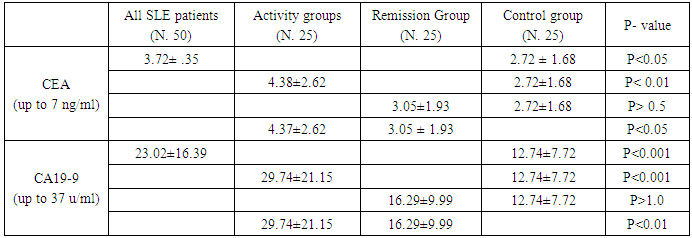

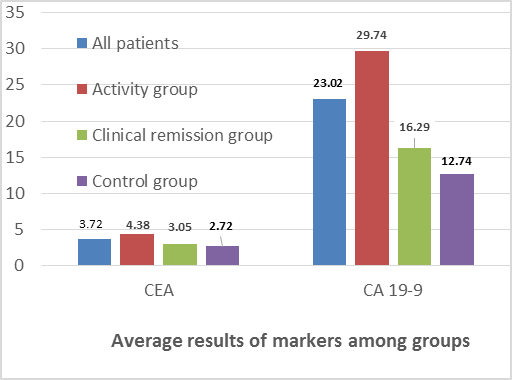

3.2. Relation between Absolute Serum Concentrations of (CEA and CA19-9) among Different Groups

- As regard absolute serum concentrations of CEA, the mean serum levels of active, clinical remission and control groups were (4.38 ± 2.62, 3.05 ± 1.93 and 2.72 ± 1.68 respectively). There was significant difference between SLE patients compared to control group (3.72 ± 2.35 vs. 2.72 ± 1.68) (p<0.05), also significant increase between activity compared to clinical remission group (p<0.05) and control group (p<0.01). But there was no significant increase between clinical remission and control groups (p > 0.5) as in (Table 2).

| Figure 1. Average CEA and CA19-9 among groups |

|

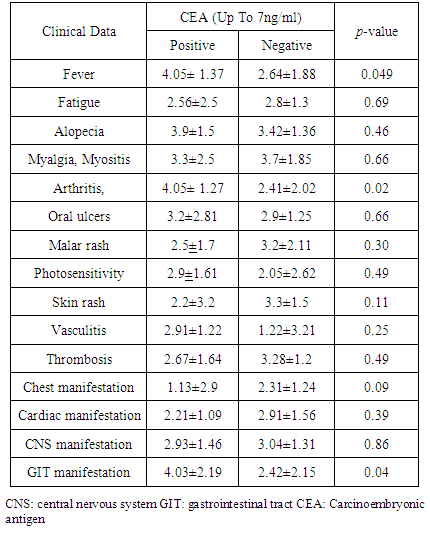

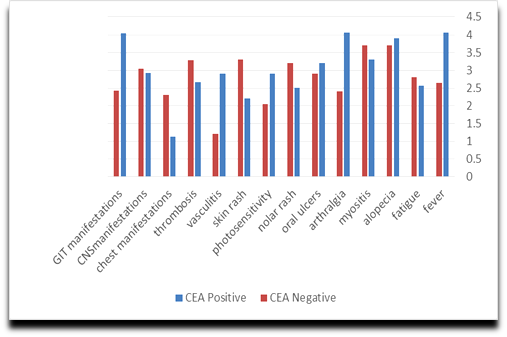

3.3. Serum Levels of CEA and Clinical Data in SLE Patients

- There was a significant increase of CEA serum levels in patients with fever, gastrointestinal tract manifestations and arthralgia/arthritis (P<0.05) in comparison to other patients (Table 3 and Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Relations between (CEA) and clinical data in SLE |

|

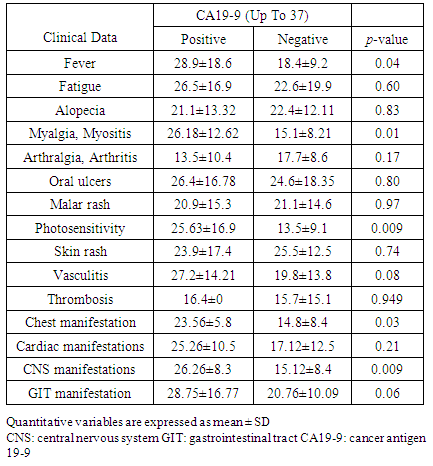

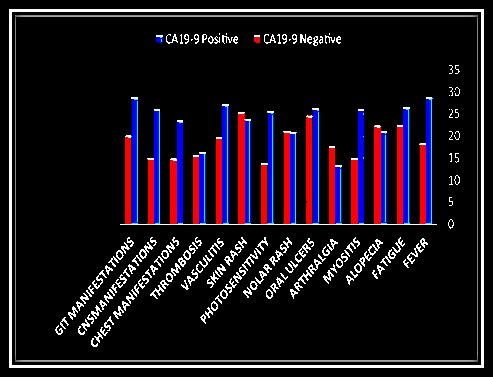

3.4. Serum Concentrations of CA19-9 and Clinical data in SLE Patients

- There was significant increase of serum concentrations of CA19-9 in patients presented with fever (P<0.05), myositis (p<0.001), photosensitivity (p<0.05), CNS manifestations (p<0.01) and chest manifestations compared to other patients (Table 4, Figure 3).

| Figure 3. Relations between CA 19-9 and clinical data in SLE |

|

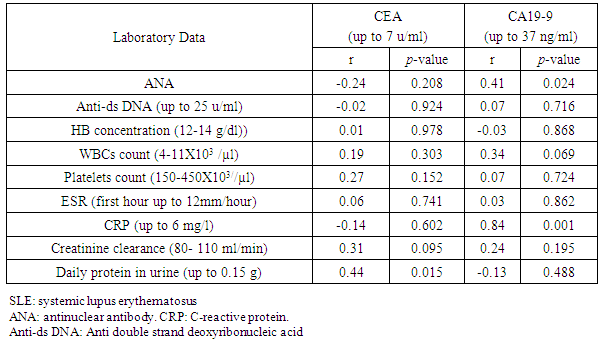

3.5. Correlations between Serum Concentrations of (CEA and CA19-9) and Laboratory Data in SLE Patients

- There was significant positive correlation between CEA concentration and daily urine proteins (r=0.44; P>0.015), CA19-9 concentration correlated with ANA (r=0.42; P> 0.05), and CRP (r= 0.84: P<0,001) as in (Table 5).

|

3.6. Correlation between Serum Concentration of (CEA and CA19-9) in SLE Patients

- There was significant positive correlation (r=0.47; P>0.01) between CEA and CA19-9 concentrations.

4. Discussion

- Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease mediated by autoantibodies that recognize self-antigens as foreigners. These antibodies are produced against the components of the cell nucleus. The abnormal immune response results in target tissue injury and the subsequent inflammatory reaction affects various organ functions [15].CA 19‐9 is expressed on the epithelia of the fetal stomach, intestine, liver and pancreas, traces can be detected in adult gastrointestinal tract and lung tissue. Greater amounts are found in saliva, bile, ovarian cyst fluid, seminal fluid, amniotic fluid, gastric and duodenal secretions and urine [14].Tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) may be involved in the pathogenesis and/or laboratory diagnostics of autoimmune- inflammatory diseases. They are involved in cell adhesion by their sialylated carbohydrate motifs. Thus most TAAs as CEA and CA19-9 are expressed on the surface of inflammatory leukocytes, as well as tumor cells [6]. TAAs act an important role in inflammation and may play a pro-inflammatory effects similar to interleukins in the pathogenesis of SLE [16]. Shedding from the cell surface, they become soluble and can be detected in the patients' sera [7]. Significant difference was observed between the two groups of SLE in our study, CEA and CA 19-9 was significantly higher in active group compared to clinical remission group. This may prove that TAAs have a role in inflammatory processes, this findings in agreement with Jamaludin et al, [13] who found elevated serum CA19-9 in association with Hashimoto thyroiditis that returned to normal levels during improvement.When comparing the percentage of SLE patients and control subjects with elevated serum TAA levels (serum concentrations above the upper normal limit), significantly more SLE patients were ‘TAA positive’ for CEA and CA 19-9 than healthy subjects.In addition, when mean serum levels were analyzed, the serum concentrations of CEA and CA19-9 were also elevated in SLE in comparison to controls. Thus, our data suggest that CEA and CA19-9 possibly may be involved in the inflammatory process underlying SLE. As discussed above, elevated levels of CEA and CA19-9 have been detected by other investigators [6].In agreement with Szekanecz et al [6] who found higher positive levels of serum CEA in SLE compared to normal controls (35.5% vs. 20%), higher than ours for active, remission and control groups (20%, 12% and 8% respectively). These differences may explained by difference in number of patients, controls and different races. In contrast they found CA19-9 positive percentage (7% vs. 2%) lower than ours (14% vs. 4%). These may due to higher positivity of patients in activity group 24%.Insignificant higher concentrations has been detected of both CEA and CA19-9 in clinical remission group compared to normal controls, this indicate their role as inflammatory mediators in autoimmune diseases.In accordance with other studies on other autoimmune diseases as in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Szekanecz et al., [8] concluded that some TAAs including CA19-9, CA125, and CA15-3, carbohydrate antigens with adhesive properties, exert increased production in RA.The tumor markers may also be correlated with systemic organ manifestations and disease activity in SLE. Increase production of CEA and CA19-9 has been associated with renal involvement, in agreement with Szekanecz et al, [6], our study detected positive correlation between serum concentration of CEA and fever, GIT manifestations and arthritis in SLE patients. While higher serum concentration of CA19-9 were associated with fever, myositis, photosensitivity, CNS and chest manifestations. In our study there was positive correlation between CEA concentration and total 24 hour's urine protein, CA19-9 concentration and (ANA, CRP) in SLE patients.In agreement with Szekanecz et al, [6] our study revealed that there is significant correlation between serum concentrations of (CEA with CA19-9).

5. Conclusions

- Our results and the results of others which showed the relation between TAAs, organ involvement and laboratory data in SLE patient may explain the role of tumor-antigens in SLE disease. These tumor-antigens may exert adhesive properties during the inflammatory process. Thus, CEA and CA19-9 may be involved in adhesive interactions underlying autoimmune inflammation in SLE. These tumor antigens may also be correlated with severity of organ manifestations and disease activity in SLE. We suggest that the determination of serum tumor antigens levels may have relevance in pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, organ involvement and assessment of disease activity in SLE. Different populations and races may express and produce variable levels of TAAs during autoimmune inflammatory processes.

6. Recommendations

- We have to take in consideration SLE as a possible cause of increased concentrations of some tumor markers when we interpret the results of higher concentrations.We have to follow up SLE patients with positive TAAs to predict early malignant transformation especially those with organ diseases [10]. Evaluation of tumor markers in SLE in each organ involvement apart from each other.To the best of our knowledge, few reports discuss the relation between CEA and CA19-9 in SLE disease.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML