-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Biochemistry

p-ISSN: 2163-3010 e-ISSN: 2163-3029

2015; 5(1): 15-21

doi:10.5923/j.ajb.20150501.03

Bat-26 is Associated with Clinical Stage and Lymph Node Status in Schistosomiasis Associated Bladder Cancer

Samah Mamdouh 1, Ayman M. Metwally 2, Ahmed M. Aref 3, Hussein M. Khaled 4, Olfat Hammam 5, Mohamed A. Saber 1

1Biochemistry Department, Theodor Bilharz Research Institute, Cairo, Egypt

2Technology of Medical Laboratory Department, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Misr University for Science and Technology, 6th October, Egypt

3Biology Department, Modern Sciences and Arts University .6th October, Egypt

4Department of Medical oncology, National Cancer Institute, Cairo, Egypt

5Pathology Department, Theodor Bilharz Research Institute, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Ayman M. Metwally , Technology of Medical Laboratory Department, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Misr University for Science and Technology, 6th October, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

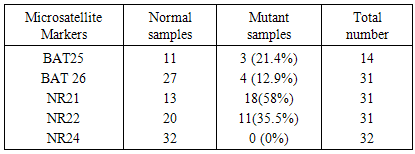

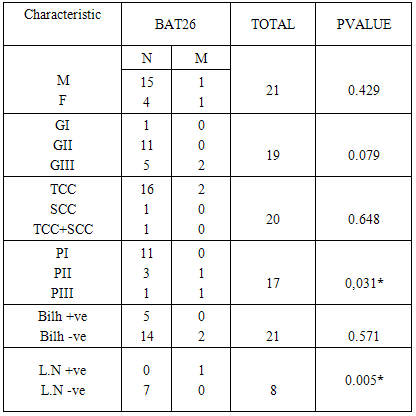

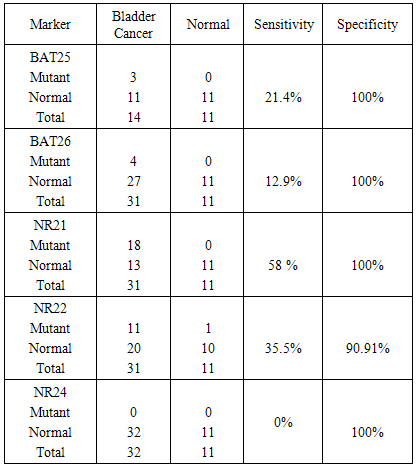

Background: Carcinoma of the urinary bladder is the most common malignancy in Egypt in which infection with Schistosoma haematobium is prevalent. This type of malignancy has different characteristics than that observed in the western world. We studied 5 microsatellite instability markers in exfoliated urinary samples from schistosomiasis associated bladder cancer cases and compared the results to the clinicopathological data of the patients. We also studied the sensitivity and specificity of these markers. Material and methods: The study included 32 histopathologically diagnosed BC patients and 11 age and sex matched normal controls. DNA was extracted from the exfoliated urinary cells and PCR was done and the product was separated by 12% PAGE. BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22 and NR-24 mutations were evaluated. Results: MSI in at least one marker was observed in 71.87% of BC cases. Mutations in BAT 25 (21.4%), BAT-26 (12.9%), NR-21 (58%), NR-22 (35.5%) were observed. No mutation was observed for NR-24 (0%). BAT 26 mutation was significantly associated with both tumor stage (P 0.03) and L.N metastasis (p 0.005). BAT25 was 21.4% sensitive and 100% specific. BAT26 mutation was 12.9% sensitive and 100% specific. NR21 was 58% sensitive and 100% specific. NR22 was 35.5% sensitive and 91% specific. NR24 was 0% sensitive and 100% specific for diagnosis. Conclusions: BAT26 mutation is significantly associated with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer. All the tested markers showed high specificity. NR21 showed the highest sensitivity. More studies are needed to detect the prognostic significance of MSI in bladder cancer.

Keywords: Bladder Cancer, Schistosomiasis, MSI, Clinicopathological data

Cite this paper: Samah Mamdouh , Ayman M. Metwally , Ahmed M. Aref , Hussein M. Khaled , Olfat Hammam , Mohamed A. Saber , Bat-26 is Associated with Clinical Stage and Lymph Node Status in Schistosomiasis Associated Bladder Cancer, American Journal of Biochemistry, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 15-21. doi: 10.5923/j.ajb.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Bladder cancer is the seventh most common malignancy in men worldwide, with 297,300 new cases estimated in 2008 [1]. Rates of bladder cancer are highest in Europe, North America, and Northern Africa, where Egyptian men have the highest incidence (37.1 per 100,000 person-years) and mortality rates (16.3 per 100,000 person-years) [2]. Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) is the most common histopathological type, occurring in approximately 90% of all bladder cancers in Western countries, with a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life [3-5].In Egypt, urinary bladder cancer incidence is among the highest worldwide [6, 7]. Chronic bladder infection with Schistosoma haematobium, the trematode causing urinary schistosomiasis as well as smoking are the most important risk factors for bladder cancer in Egypt [8, 9].Currently Squamous cell carcinoma represents about 30% of all bladder cancer cases [9, 10] where there is a significant shift from 60-70% of bladder cancer cases reported before the 1980’s. This may be due to Schistosoma hematobium eradication campaigns [8, 11].Radical cystectomy is still the treatment of choice for most of the cases [12]. However, the 5 year survival rate is still not satisfactory (13). Because most of the patients are presented with advanced stage of the disease, the introduction of adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not add too much to the current survival figures [14]. Extensive studies are clearly needed to discover the molecular abnormalities that may lead to bladder cancer formation and resistance to therapy. Genomic instability is a characteristic feature of almost all major human tumors. Numerous genetic and molecular alterations occur in TCC of the bladder [15]. Genetic instability by itself can lead to the development of bladder cancer [16]. Microsatellites are short repeats of nucleotide sequences of DNA, consisting of 1–5 nucleotides [17]. Because of their repeat structure, microsatellites are prone to replication errors. These errors are repaired by the DNA mismatch repair pathway (MMR) [18]. However, this pathway may fail resulting in microsatellite instability ((MSI).Tumor is classified as MSI-high (MSI-H) if it shows instability in at least 2 of 5 markers; MSI-low (MSI-L) if 1 of 5 and microsatellite stable (MSS) if none of 5. [19]Several studies have reported the presence of MSI in urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC) of the bladder [20] [21]. MSI has also been found in many cancers including gall bladder cancer, ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer [22-24].The assessment of MSI (BAT25, BAT26, NR21, NR22 as well as NR24) status can help in establishing a clinical prognosis and may predict tumor response to chemotherapy [25]. MSI can also be used as a prognostic marker for the detection of many human cancers [26].The aim of the present study is to detect the occurrence of the 5 microsatellite instability markers BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22 and NR-24 in exfoliated urinary samples from schistosomiasis associated bladder cancer cases and comparing the results to the clinicopathological data of the patients and testing the sensitivity and specificity of these markers for the detection of the disease.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

- The present study was conducted according to the guidelines of the ethical principles outlined in the declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University as well as Theodor Bilharz Research Institute, Egypt. The study included a total of 32 bladder cancer cases attending to both institutions and 11 age and sex matched normal controls.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Only new cases with clinically diagnosed bladder cancer were involved in the study. The patients did not receive any type of therapy. Selection of the patients was carried out depending on the results of both endoscopy and the histopathological examination of the removed samples.After approval of the ethical committee, urine samples were collected from the patients before being subjected to any type of therapy. For those who had radical cysctectomy as a primary treatment modality, diagnosis of bladder cancer was confirmed by histo-pathological examination of the removed tumor tissues by 2 independent pathologists.

2.3. Methods

- Voided Morning urine samples were collected from patients and normal controls into 50 ml sterile Falcon tubes before therapy and transferred to the laboratory. Samples were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 20 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was re-suspended in 1x pbs (PH7.2) and centrifuged again. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was stored at -80 until the DNA extraction.

2.4. DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Total DNA was extracted from the cells using the Abott kit.(Abbott Park, Illinois, U.S.A), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA samples were coded and stored at – 20°C until analysis. Polymerase chain reaction was performed in MJ Research PTC-100 machine. The following set of primer sequences for BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-22 and NR-24 were used (27) as shown in Table 1.

|

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 12.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data management. Chi‑square and Fisher’s exact test were used for testing proportion independence. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (or median) and frequencies (%). P value is significant at 0.05 levels.

3. Results

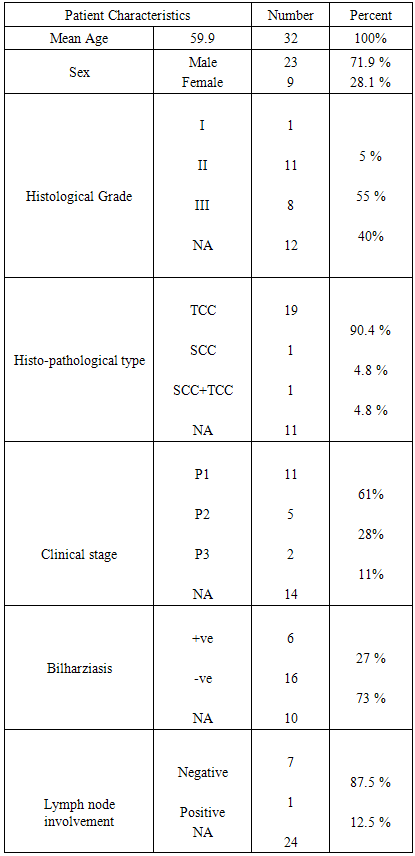

- Thirty two cases were involved in the study. The histopathological data of only 22 cases were evaluable the remaining 10 cases were histpathologically inavailable. Nine patients were females and 23 were males. The mean age was 59.1 years (± 10.7). The histopathological features of the patients are shown in (table 2).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Bladder cancer in Egypt is still a major problem where patients presented with advanced stage of the disease. Also the survival rate is still low. Early detection of the disease is needed to detect the early stages of the disease. Many advances have been made to discover a reliable marker that may detect the disease in its early stages [30] [31]. Microsatellite instability have been studied in many cancers such as colorectal cancer, melanoma, endometrial carcinoma, breast cancer and bladder cancer [32-36]. In the present work we studied the MSI in exfoliated urinary cells for 34 schistosomiasis associated bladder cancer then correlated the results to the histopathological criteria of the patients. The 5 mononucleotide markers have been studies in many types of cancer. Wong et al used BAT25, BAT26, NR21, NR22 and NR24 in endometrial carcinoma. They concluded that the best markers within the NCI panel are the mononucleotide repeats BAT-25 and BAT-26 [37]. Another study by Xicola et al was conducted on 1058 colorectal tumors, they compared the performance of two panels of markers, and they found that the pentaplex panel of mononucleotide repeats performs better than the NCI panel for the detection of mismatch repair–deficient tumors. Simultaneous assessment of the instability of BAT26 and NR24 is as effective as use of the pentaplex panel for diagnosing mismatch repair deficiency [38]. Zulueta et al. found that microsatellite instabilities are present as an apparently early event in the development of bladder cancer. [39] Our data indicated that mutation was detected in 4 microsatellites these are BAT25, BAT26, NR21, and NR22. However the remaining marker NR24 was normal. Vaish et al studied MSI in 44 superficial bladder cancer cases; he found that MSI play important role in evolution, initiation and progression in bladder tumors. [40] Although MSI have extensively studied in many types of cancer, there was a great variability between the results from study to another.Artus et al found that MSI has been observed in only one of the 17 bladder cancer studied cases [41]. However Bonnal et al investigated the prevalence of the microsatellite instability using a panel of six microsatellite markers where 3 mononucleotide repeats (BAT26, TGF betaRII, and BAX) were studied in 33 TCC samples and in four bladder cancer cell lines. They found no alteration was detected either in the 33 TCC samples analyzed or in the four bladder cancer cell lines [42].This variability may results from the etiology of the diseases from one population to another. In order to detect the clinical significance of MSI, we compared the results to the clinicopathological criteria of the patients. Among all the clinical data studied, only BAT26 was significantly associated to high clinical stage and lymph node metastasis.Vaish et al. 2005 examined BAT26 on 44 bladder superficial tumors, the results were compared to the clinico-pathological data of the patients, BAT26 was significantly associated to clinical stage [40]. The same author on 2003 found that the instability with BAT-26 was found to be 20%. Eighty-three percent of the unstable urinary bladder cancers were found to have a high grade in a superficial group, whereas only 27% MSI +ve were muscle invasive cancers [43]. Also Burgos et al studied microsatellite instability on DNA extracted from exfoliated urinary samples from 165 bladder cancer samples. They found that the biggest number in MSI was found in superficial tumors and GI-GII tumors [44]. However, Catto et al. 2003 did not find any significance between MSI and tumor stage in TCC of 84 bladder cancer cases [45]. For other types of cancer, Beghelli S et al. found that gastric cancer is significantly associated to lower stage; he also found that only stage II cancers showed a significant effect of MSI status on survival [46]. However, Ju etal. found that there is no significant association between MSI status and clinical stage in endometrial adenocarcinoma [47]. The same result was found in esophageal cancer where there was no significance between BAT26 and any of the clinicopathological data including clinical stage [48].Our Study indicated that there is a significant association between BAT26 instability and lymph node metastasis.Kazama et al. found that microsatellite instability in poorly differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma is significantly associated with lymph node involvement. [49]. Also Malesci et al. found a strong association between MSI and decreased lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer [50]. In gastric cancer, BAT26 alteration was highly correlated with less lymph node metastasis [51]. From the above data it seems that MSI instability is different from tumor to another. Regarding the bladder cancer, the data from our study as well as the other studies indicate that MSI especially BAT26 is almost present in both superficial and invasive bladder cancer. Regarding the correlation between MSI and the clinicopathological features of bladder cancer, although our study showed a significant association between BAT26 and clinical stage and lymph node metastasis, but we cannot reach a final conclusion regarding the association of MSI to the other clinicopathological criteria which may be due to the low number of cases in our study.

5. Conclusions

- BAT26 mutation is significantly associated with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer. All the tested markers showed high specificity for the detection of the disease. Among the 5 markers, NR21 showed the highest sensitivity. More studies are needed to detect the prognostic significance of MSI in schistosomiasis associated bladder cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank Prof. Nelly Ali-Eldin, Department of Cancer Epidemiology and Biostatistics, National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt for the statistical analysis of the work.

Competing Interests

- We have read and understood the journal policy on disclosing conflicts of interest and we declare that we have no financial competing interests.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML