-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Materials Science

p-ISSN: 2162-9382 e-ISSN: 2162-8424

2015; 5(C): 203-208

doi:10.5923/c.materials.201502.39

Flexural Strength Analysis of Areca Frond Reinforced Starch Based Composites by Taguchi Method

Srinivas Shenoy H., Suhas Y. Nayak, Ramakrishna Vikas S., Vishal Shenoy P., Navaneet Krishna Vernekar

Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal University, Manipal, India

Correspondence to: Suhas Y. Nayak, Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal University, Manipal, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

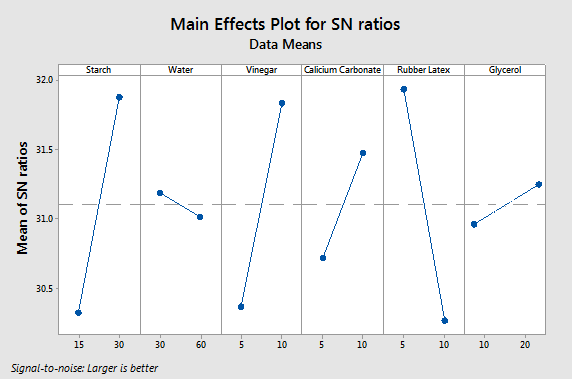

Recycling of materials effects the environment and thus greater impetus is being given to develop materials like biodegradable composites from renewable sources. A biodegradable composite is made up of natural reinforcements and matrices that are environment friendly. Natural reinforcements in matrices that are biodegradable have several advantages like reasonably good specific modulus, low cost and abundant availability in comparison to synthetic reinforcements. In this study areca frond fibres are reinforced with calcium carbonate and rubber latex as binders, starch, and water, vinegar as base material and glycerol as plasticizer. Matrix ingredients included corn starch (15-30 g), water (30-60 g), vinegar (5-10 g), calcium carbonate (5-10 g), rubber latex (5-10 g) and glycerol (10-20 g). A fusion of hand layup and compression moulding technique was used to prepare composite panels. Taguchi method is an optimization technique to reduce number of desired experiments while maintaining quality of data collected and for finding the significance of various factors and their levels which affect the response. Taguchi method with L8 orthogonal array with six factors and two levels combination was used for experimentation. Specimens for the flexural tests were cut out from the prepared panels and tests were performed in accordance with ASTM standards. Maximum flexural strength of 48.54 MPa was obtained with a combination of corn starch (30 g), water (30 g), vinegar (10 g), calcium carbonate (10 g), rubber latex (5 g) and glycerol (20 g). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the obtained data and S/N (signal to noise) ratios for larger the better quality characteristics was calculated. Results indicated that rubber latex has the maximum effect (33.18%) on flexural strength of the biodegradable composites followed by corn starch, vinegar, calcium carbonate, glycerol and water.

Keywords: Areca frond, Calcium carbonate, Rubber latex, Corn starch, Biodegradable, Hand layup, Taguchi method

Cite this paper: Srinivas Shenoy H., Suhas Y. Nayak, Ramakrishna Vikas S., Vishal Shenoy P., Navaneet Krishna Vernekar, Flexural Strength Analysis of Areca Frond Reinforced Starch Based Composites by Taguchi Method, American Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 5 No. C, 2015, pp. 203-208. doi: 10.5923/c.materials.201502.39.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Evolution of developing green composites is gaining momentum and it has been a key alternative to fossil fuel based materials. The concept of green composites is to deliver the optimal functional requirements and maximize performance of the blend. Composites thus manufactured by natural fibres and environment friendly matrix are extensively used due to its advantages like abundant availability, ease of treatment for natural fibres, light weight, low cost, high specific modulus and biodegradability. Natural fibre characteristics vary with varying cultivation conditions, the chemical constituents is mainly of cellulose, lignin, pectin, hemicellulose, water soluble elements and residual ash along with other organic materials [1]. K Murali Mohan Rao et al. [2] investigated the cross-sectional shape, density and tensile strength of natural fibres such as vakka, date and bamboo. The cross-sectional shape like circular, oval was determined by optical laser beam equipment for tensile testing. Picnometric procedure was adopted for measuring density and percentage moisture. Rajan et al. [3] subjected areca nut husk fibres to bio softening so as to reduce the lignin content of the fibres thus facilitate better fibre strength properties. Padmaraj N H et al. [4] studied and compared the tensile behaviour of untreated areca nut fibres with that of wheat flour, sugar, and jaggery treated fibres. R P Swamy et al. [5] fabricated composite laminate based on areca fruit fibres with different composition of phenol formaldehyde using hydraulic hot press technique. Tensile strength, bending strength, moisture absorption test and biodegradability were assessed. Ming Qiu Zhang et al. [6] investigated the properties of sisal fibre / plasticized wood flour composites fabricated using hot press technique. The variations in tensile, flexural, impact and thermal properties of these composites were discussed. A Varada Rajulu et al. [7] investigated the interfacial bonding and mechanical properties of natural fibre hildegardia populifolia reinforced partially biodegradable styrenated polyester composites. The composites were fabricated using a combination of hand layup and compression moulding technique. W L Lai et al. [8] evaluated unsaturated polyester composites reinforced with woven kenaf and betel palm fibres fabricated using vacuum bagging technique to study its morphology, physical and mechanical properties. Han-Seung Yang et al. [9] investigated the water absorption and mechanical properties of rice husk flour reinforced polyolefin bio-composites and compared the results with solid woods composites, medium-density fibreboard and commercial particleboard. C V Srinivasa et al. [10] studied the interfacial bonding, water absorption, tension, compression, bending, impact and hardness aspects of alkali treated areca husk fibre reinforced epoxy composites. A combination of hand layup and hydraulic compression was used to fabricate the composites. Xiaofei Ma et al. [11] studied the bio-degradable composites made of polypropylene carbonate reinforced with granular corn starch using screw extrusion technique. Tests were conducted to study the morphology, thermal properties and mechanical properties of polypropylene carbonate /starch composites to examine the effect of succinic anhydride. Qiao Junjuan et al. [12] studied composites made from poly ethylene- co-vinyl alcohol, poly propylene carbonate, calcium carbonate and starch. Composites were fabricated by melt blending technique and its thermal and bio-degradable properties were examined. Dekun Zhang et al. [13] studied the synthesis and characterization of polyvinyl alcohol, nano-hydroxyapatite and natural silk composite hydrogel using repeated freezing and thawing method. Tests designed according to Taguchi’s orthogonal array of experimentation were used to study stress relaxation behaviour, water content, elastic modulus, and creep characteristics of the composite. K Majdzadeh-Ardakani and B Nazari [14] used melt extrusion technique to fabricate thermoplastic starch/poly vinyl alcohol/ clay nano-composites. The effects of the constituents on clay intercalation and mechanical properties were investigated based on the Taguchi experimental design. Srinivas Shenoy Heckadka et al. [15] have studied the flexural strength of the areca frond fibres reinforced with starch, methylcellulose, and resorcinol based matrix material. Fabrication techniques such as hand layup and compressing moulding were adopted. Taguchi L8 orthogonal array was used for experimentation. Natural fibres such as vakka, date, bamboo, areca husk, betelnut, sisal, Hildegardia populifolia, kenaf, areca frond have been widely used as reinforcements in thermoplastic and thermoset composites [2-15]. Phenol formaldehyde, saw dust, polyester, epoxy, poly propylene carbonate/starch, ethylene- co-vinyl alcohol/starch, calcium carbonate, corn starch [5-15] have been extensively utilized as matrix material. Thus one of the prominent raw materials which are renewable and used for the production of biodegradable composites is corn starch which is gaining importance for the development of green composites. Traditional fabrication techniques such as hot pressing technique, compression moulding, vacuum bagging [5-8], hydraulic compression, screw extrusion technique, melt blending technique, pneumatic pressing [10-15] have been widely used. Biodegradable composites prepared using natural fibres and eco-friendly matrices demonstrate good mechanical properties such as flexural, tensile and compression and can be used in various applications such as dash board of a car, locomotive seating side panels, small boat panels, civil structures and light loaded furniture [16]. Natural fibre such as areca frond has not been studied to a large extent. So the present study makes use of a combination of hand layup and compression moulding technique to fabricate areca frond fibres reinforced starch based biodegradable composite. Flexural strength of the biodegradable composite is determined and analysed by using an optimizing technique.

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Fibre Extraction and Treatment

- Areca fronds were obtained from local areca plantations. The fronds were cleaned and immersed in water for 5 days. The soaking process loosens the fibres in the fronds thus making it easy to extract them using a wire brush [5]. Fibres were repeatedly washed with fresh water to remove the remaining flabby fibres and were allowed to dry at room temperature. The dried fibres so obtained are termed as “untreated fibres”. The extracted fibres were treated with 1 N solution of sodium carbonate. A volume of 15 times the weight of the fibres was used for the treatment. Fibres were treated by immersing them in an alkaline solution for 8 h and drying them for 24 h, both at room temperature to get “alkali treated fibres” [4]. Figure 1 shows the extracted and treated areca frond fibres. Chemical composition of areca frond fibres is hemi cellulose (35-64.8%), lignin (13-24.8%) and ash (4-4.4%) [17].

| Figure 1. Extracted and treated areca frond fibres |

2.2. Matrix Preparation

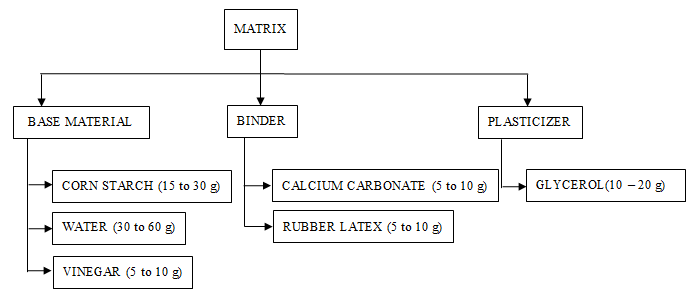

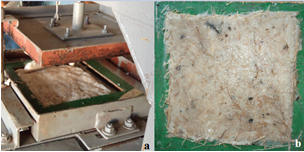

- Figure 2 shows the basic ingredients of the biodegradable matrix. The matrix constituents namely, corn starch powder, water and vinegar are weighed to the nearest 1mg. The weighed constituents are mixed in a vessel using a magnetic stirrer. Plasticizer and binders are added and stirred for 15 minutes. The mix is then transferred to a bowl and heated at 140C. Heating is continued till it transforms to a semi-solid state [5]. The fibres are added to the semi-solid mix, mixed thoroughly and emptied in to a mould of dimensions 250 mm x 250 mm. The mix in the mould is spread evenly using hand. Figure 3 shows the preparation of the composite. The mix is compacted using a pneumatic press. The mould is coated with a releasing agent to prevent sticking of the composite. The composites are next cured in a steam heated chamber at 85C for duration of 24 h.

| Figure 2. Constituents of biodegradable matrix |

| Figure 3. Preparation of biodegradable matrix composites – (a) Mixed constituents ready for compaction (b) Compacted Laminate |

2.3. Taguchi Concept

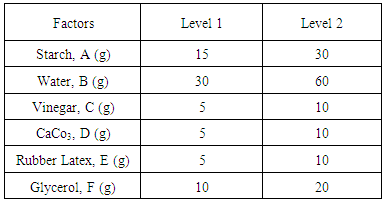

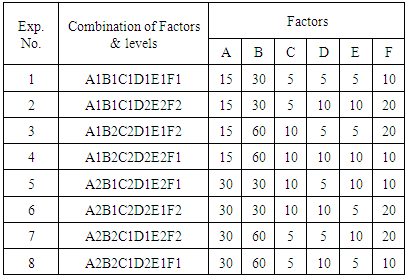

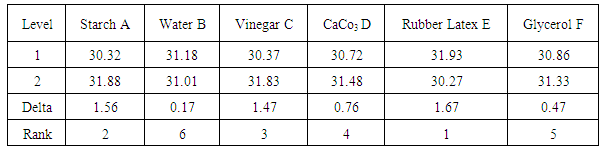

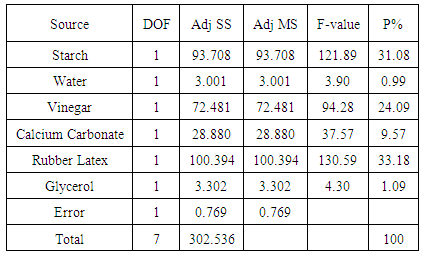

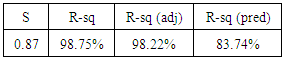

- Corn starch, water, vinegar, calcium carbonate (CaCo3), rubber latex and glycerol were the factors considered for this study. The factors and their levels are presented in Table 1. Work carried out in the past, practical features and screening test results were the basis for selecting the factors and their levels. A standard L8 orthogonal array with six factors and two levels for each factor was employed (Table 2). Response calculations are based on flexural strength.

|

|

2.4. Signal to Noise (S/N) Ratio

- Taguchi design helps to identify control factors which minimize variability in a process by reducing the effects of factors which are uncontrollable. Such uncontrollable factors are known as noise. Parameters that can be controlled are referred to as control factors, while noise factors are those which cannot be controlled during a process but can be controlled experimentally. Experiments based on Taguchi design often use a two-step optimization process. In the first step, S/N ratio is used to determine the control factors that minimize variability. In the second step, control factors which bring the mean to target and that have minimal or zero effect on the S/N ratio are identified. Signal-to-noise ratio measures the variation of the response (output) in relation to the target value under different noise conditions. Out of the three quality characteristics, “larger is better” is considered. Equation 1 gives its mathematical expression.

| (1) |

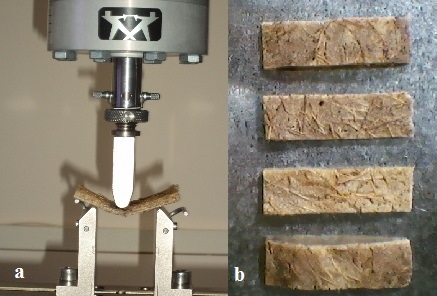

2.5. Flexural Testing

- Composite specimens were tested for flexural strength on and Instron Universal Testing Machine (Model 3366). Experiments were performed according to ASTM D790 [18- 20]. Test specimens were cut to dimensions 94 x 12 x 5 mm. Figure 4 shows Instron 3366 setup and testing. Testing was done at a constant cross head speed of 2 mm/min.

| Figure 4. Flexural specimen testing |

3. Results and Discussion

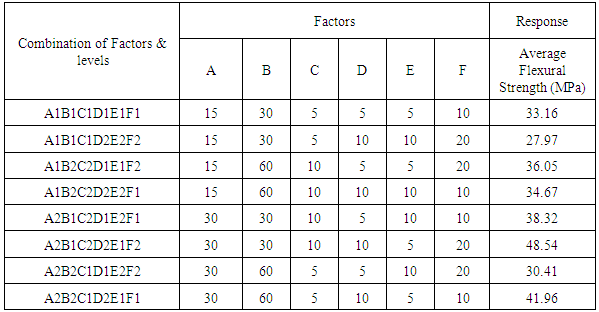

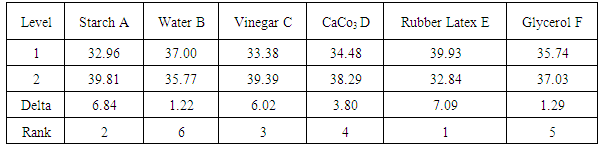

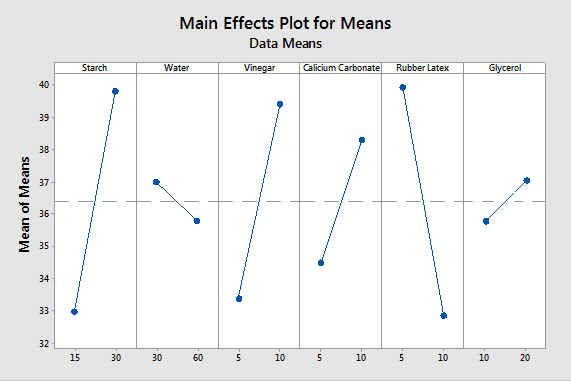

- Results of the flexural strength tests performed on the fabricated biodegradable composite by varying the constituents such as corn starch, water, vinegar, calcium carbonate, rubber latex and glycerol are given in Table 3. The maximum flexural strength of 48.54 MPa was obtained for the combination A2B1C2D2E1F2 i.e. with corn starch (30 g), water (30 g), vinegar (10 g), calcium carbonate (10 g), rubber latex (5 g) and glycerol (20 g). Composite with following grouping A1B1C1D2E2F2 i.e. with corn starch (15 g), water (30 g), vinegar (5 g), calcium carbonate (10 g), rubber latex (10 g) and glycerol (20 g) resulted in minimum flexural strength of 27.97 MPa.

|

|

| Figure 5. Main effect plots for means |

| Figure 6. Main effect plots for S/N ratios |

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The following conclusion could be drawn from the study• Optimal combination considering all factors and levels for the biodegradable composite is A2B1C2D2E1F2.• Composition of the optimal combination corn starch (30 g), water (30 g), vinegar (10 g), calcium carbonate (10 g), rubber latex (5 g) and glycerol (20 g). • The factor combination A2B1C2D2E1F2 resulted in Maximum flexural strength of 48.54 MPa. • Rubber latex has the maximum effect on the flexural Strength.• Water has the minimum effect on the flexural strength.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are indebted to Dr Divakara Shetty S., Head of the Department, Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering for permitting us to make use of the Advanced Material Testing and Research Laboratory. The authors are thankful to Dr B. Satish Shenoy, Head of the Department, and Dr Dayanand Pai, Professor, Department of Aeronautical and Automobile Engineering for allowing us to use Advanced Composite and Material Testing Laboratory. The authors thank Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Manipal for permitting us to use material testing facilities. The authors would also like to thank Dr Raghuvir Pai B. Professor and Dr M Vijaya Kini, Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering for their motivation, support, and expert guidance throughout the research work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML