-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Tumor Therapy

p-ISSN: 2163-2189 e-ISSN: 2163-2197

2015; 4(1A): 35-41

doi:10.5923/c.ijtt.201501.06

E-Learning Experience in Promoting the Development of Epistemological Beliefs amongst Tripoli University Students

Hussam-Eddin Alfitouri Elgatait

Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Hussam-Eddin Alfitouri Elgatait, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study focuses on the limitations in using e-Learning tools among the majority of students at Libyan Higher Education Institutions (LHEIs). The reasons behind this remain unconfirmed; however, it may be related to student beliefs about behavioral aspects being integrated through e-Learning. Thus, the question of whether the e-Learning environmental setting presented by LHEIs has the potential to witness the students’ epistemological belief and becomes more relevant. As such, the effects of specific factors related to the use of e-Learning that influence Libyan students’ epistemology (in terms of naïve and sophisticated beliefs) in the use of e-Learning were investigated.

Keywords: Epistemological beliefs, E-learning, Committee learning

Cite this paper: Hussam-Eddin Alfitouri Elgatait, E-Learning Experience in Promoting the Development of Epistemological Beliefs amongst Tripoli University Students, International Journal of Tumor Therapy, Vol. 4 No. 1A, 2015, pp. 35-41. doi: 10.5923/c.ijtt.201501.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Several learning courses have been delivered to students in different universities since 2002, followed by the integration of e-Learning into the Libyan higher education institutions (LHEIs) in 2005 (Rhema & Miliszewska, 2012). This integration continues to progress to increase student willingness and motivation to learn by creating and discovering potential ways for conducting learning and training. The aim is to enhance the overall management of technology adoption and improve the standard of education offered in Libya (Al-teer, 2007). Hence, the current demand from higher education institutions throughout the world regarding the use of e-Learning has slightly encouraged students to adapt online learning techniques, which appear based on the contextual trends of virtualization, internationalization, and lifelong learning that are part of society in general (Collis, 2001). This pushes traditional universities to change considerably their instructional methods to keep pace with developments spurred by the internet. However, in many developing countries, it is not possible for all university students to use e-Learning (Ali, 2003), which has an effect on beliefs associated with the use of e-Learning.A review of the literature on online instruction and learning environments has demonstrated a variety of learning consequences. While there is information about commonly constructive levels of engagement and satisfaction with online learning environments, high dropout rates and records of “student distress” are not exceptional (Gibbs, 2003; Schwartzman, 2006). However, the relationship between core elements of e-Learning and a learner’s level of epistemological beliefs in most developing countries (including Libya) is not characteristically discussed and addressed as important variables in the online learning environment, especially in Libyan regional universities. Therefore, it can be argued that the development of students’ epistemological beliefs may help to clarify discrepancies in using online learning tools when combined with educational strategies (Wayman & Stringfield, 2006).Understanding the extent of the effect of changes in epistemological beliefs on students in a university context could help in explaining the growing number of criticizing students’ behavior toward the available learning and teaching tools by university lecturers in Libya (Kenan, 2009; Rhema & Miliszewska, 2010). This has led lecturers to believe that students have become more individualistic (or self-independent) and tend to show no concern about provided learning materials, especially online resources (Abdelraheem, 2006). Such attitudinal change may be a cause of the low performance in universities in Libya and across a number of African countries. This is considered one of the most contentious problems in such institutions (Elansari, Khalil, Crone, & Stock, 2014). Further, Schommer (1994) believes that the need for enhanced understanding of the nature of epistemological beliefs will increase as the given society becomes more developed. Moreover, this will occur in situations where high-level learning and critical, independent, and creative thinking of individuals becomes progressively more important (Blumenthal, Grossmann, Golatowski, & Timmermann, 2008). As the Libyan society is slowly becoming more involved in aspects of information technology, it is important to understand Libyan students’ epistemological beliefs affecting their achievement in which Schunk and Zimmerman (2012) suggested that factors such as self-regulation and motivation are important for such examination.The move to a more developed society through adopting technological advances such as the online learning environments is key for the survival of the Libyan society. Therefore, to lead such a change effectively, the education system may benefit from the availability of online learning tools, due to the lack of core learning resources currently available to students at Libya’s regional sized universities (the regional size universities consists of public institutions that offers undergraduate and postgraduate programmers with approximately of 12000 students every year). However, development in Libya means that it is a more information-oriented country that requires a greater understanding of students’ epistemological beliefs.

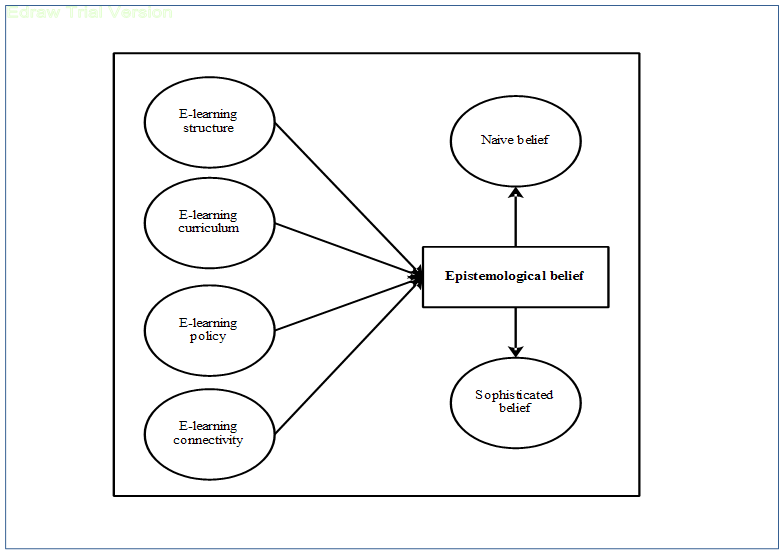

2. Research Model

- We constructed our theoretical understanding of e-Learning experiences form Cobern’s (1993) model in which he considered individual belief as the reason, thinking, comprehension, and interpretation of one’s understanding about knowledge delivered by any means. It can consist of environmental factors, technological factors or students’ related behaviours. As such, the empirical investigation of the literature showed that aspects related to structure, curriculum, policy, and connectivity form the essential e-Learning experience which were examined by the researcher in this study. In addition, the researcher also used the categorization of personal epistemological beliefs by Schommer (1990) whereas the general view of Cobern’s model was specified into Schommer’s view of naive and sophisticated beliefs. Therefore, students’ naïve and sophisticated beliefs were examined in this study to determine its impact on developing student’s motivation and self-regulated learning. These aspects were always addressed to have an influence on student’s characteristics and behavioural changes. As such, the view driven from the cognitive development theory by Piaget’s and Eames (1980) were adapted to explain the nature of naïve and sophisticated impact on one’s motivation to use e-learning. Meanwhile, the researcher also used co-regulated learning model by McCaslin and Good (1996) to explain the dimensional effect of these two epistemological aspects on students self-regulated learning in the Libyan context.The focus of the epistemological beliefs related to learning and academic development tend to originate from Perry (1970), who created an active research topic. Epistemology is seen as a branch of philosophy related to the nature of knowledge and the justification of one’s beliefs. There are numerous methodological examinations of beliefs that tend to depend on the theoretical orientations upon which a great deal of emphasis is placed (Felbrich, Kaiser, & Schmotz, 2012; Voss, Kleickmann, Kunter, & Hachfeld, 2013). This study illuminates Schommer’s perspective. Other researchers on epistemology have involved studying adolescents and young adults using time-consuming instruments such as production tasks and interviews to evaluate beliefs (Lahtinen & Pehkonen, 2012). However, Schommer suggests a quick sample of a self-reporting questionnaire that can enable researchers to study individuals in a short amount of time.Schommer’s perspective differs from other theoretical perspectives because she provides a more simplistic and quantified view of epistemology by adhering to the view that individuals tend to process multiple beliefs on the nature of knowledge and learning. These beliefs tend to exist as a multidimensional system or even somewhat independent beliefs. One can develop an argumentative premise in contrast to the work of Perry where the individual’s epistemology is quite complex and can easily be captured on one learning based dimensions. According to Schommer, the term ‘system’ is the notion that there is more than one system that constitutes personal epistemology; system suggests that these beliefs are able to develop synchrony. The theoretical lens of Schommer’s perspective reveals that there are four dimensions of epistemological beliefs that range from naïve to highly sophisticated: the structure of knowledge that ranges from integrated concepts to isolated parts, the stability of knowledge that evolves, the rapidity of learning, the ability to be able to learn from birth (Schommer, 1994a, 1994b; Schommer-Aikins & Easter, 2006). The potential of examining beliefs related aspects on users use of technology has been highly recommended in many previous studies (Cools, Evans, & Redmond, 2009; Tsai, 2008). This is in particular crucial in a learning environment, because universities permanently have to deal with substantial changes of the learning contexts from different organizational and technological dimensions. However, epistemic beliefs in university settings can influence the perception of purposes for e-learning (Pieschl, Stahl, & Bromme, 2008). Nevertheless, it can also effects how learning opportunities are perceived and how, consequently, learning strategies are selected and developed from the students perceptive. Therefore, the potential of examining epistemic beliefs of students can help determine the perception of students to use e-learning (Pieschl, et al., 2008). Cano and Cardelle-Elawar (2008) added that an examination of epistemic belief effects on one’s use of e-learning system is supposed to support to make use of e-learning opportunities. In a study with university students, some few evidences were extracted regarding the effects of epistemic beliefs on the usage of ICT for learning and instruction. This led the researcher to consider the potential of epistemological beliefs in influencing all stages of self-regulated learning by affecting students’ internal standards for metacognitive monitoring and controlling and consequently influencing the processes of metacognitive calibration. In this context, the term calibration is transferred from its classical application (Tsai, 2008) to also refer to the alignment between external conditions, i.e. the complexity of the learning material, and students’ learning processes (Cools, et al., 2009). Furthermore, this study assumed that Libyan students with more ‘sophisticated’ epistemological beliefs should be more flexible than students with more ‘naïve’ epistemological beliefs in adapting their whole learning process to different external conditions such as the demands of the learning content. Therefore, one possibility to test our assumption is to examine the effects of current e-learning settings on students’ epistemological beliefs to develop their self-regulated learning and motivation.Soong, Chan, Chua, and Loh (2001) verified that the possible e-learning factors that may impact students use are human factors, technical competency of both instructor and student, e-learning mindset of both instructor and student, level of collaboration, and perceived information technology infrastructure. They recommended that all these factors should be considered in a holistic fashion by e-learning adopters. According to studies conducted by Dillon & Gunawardena (1995), three main variables affect the effectiveness of e-learning environments: technology, instructor characteristics, and student characteristics. Helmi (2001) concluded that the three driving forces to e-learning are information technology, market demands, and education brokers such as universities. In an attempt to provide a pedagogical foundation as a prerequisite for successful e-learning implementation, Bates (2005) discussed the importance of organization structure in facilitating the use of e-learning systems in terms of the institutional support, course structure, student support, and faculty support. Hence, curriculum was always found to influence the use of e-learning in which it must be rich and related to the student’s belief (Gold, et al., 2004).On the other hand, Selim (2007) stated that environmental structure is an effective element in favouring the utilization of e-learning in the higher education context. Uden, Wangsa, & Damiani (2007) as well addressed the need for considering the process of designing a new e- learning structure when it comes to implementing it. This concern was found to be shared with MacDonald’s & Thompson (2005) one where they found that dimensions of structure, content, delivery, service, and outcomes must work in concert to implement a quality e-Learning course. They also emphases on the other key themes concerns about learner needs and belief to become able to use and participant in online related activities. Learning believe about using e-learning was then considered as an important aspect to look at when examining or developing students’ behavioural factors. De Freitas & Oliver (2005) highlighted the impact of use policy on students’ intention to use e-learning tool in which they believed that e-learning policy is beginning to take on a more significant role within the context of educational policy.As such, policy issues to use e-learning have been always referred to as the limits decision makers puts on students (Brown, Anderson, & Murray, 2007). For this reason, it is becoming increasingly important to establish what effect such policies have and how they are achieved in the LHEIs. Furthermore, issues related to connectivity were also reviewed as a common challenge for developing countries to maintain stable use of e-tools (Van Harmelen, 2006). Sharifabadi (2006) explained the importance of ensuring the linking of digital libraries and virtual learning environments to provide a meaningful connection between learning activities and learning resources. Since this connection is consider as critical aspect in most LHEIs, the researcher was motivated to look at the role of connectivity in driving students’ epistemological belief to use online tools. After all, it can be concluded that the main aim to attainment measures can be environmental, technological, and student related factors. In e-learning some of the crucial factors can be technological, such as bandwidth, hardware reliability, and network security and accessibility. While other factors can be student behavioural aspects resulted from using e-learning (engagement, interaction, etc…). The student related factors can be associated with the motivation and committed where students take responsibility of their learning pace. In this study, the researcher identified these factors as the main constructs that could drive one’s behaviour to use in different learning contexts. The factors associated with e-Learning settings presented by previous researchers (e.g., Bates, 2005; MacDonald & Thompson, 2005; De Freitas & Oliver, 2005) are from descriptive or analytical studies with certain dimensions. For parsimony and feasibility of practice, this study intends to examine the factors of structure, curriculum, policy, and connectivity to ensure the coverage of e-Learning design and operation from a holistic viewpoint and present guidelines for e-Learning management. The results presented in this study can certainly help institutions adopt e-Learning technology by overcoming potential obstacles, and hence reduce the risk of failure during implementation. Furthermore, academia can use the findings of this study as a basis to initiate other related studies in the e-Learning area.Hence, the researcher in this study addressed the main elements of structure, curriculum, connectivity, and policy to be the most common factors shared among previous studies.

| Figure 1. Research model |

3. Method

- This study employs quantitative methodology, using questionnaires to collect data. Quantitative analysis was suitable for the data analysis, and based on several statistical calculations such as the means, frequencies, and variance. This study is consider survey research since it consists on measurement procedures that involve asking questions of respondents on aspects related e-Learning experience factors and observing the influence on students epistemological belief.

3.1. Measures

- Items for the e-Learning experience were adapted from different studies. For example (Unwin, 2008) (five items for structure and five items for connectivity were modified); Setchi (2010) (five items for curriculum were modified); and (Embi, 2011) (five items for policy were modified). However, to measure students’ epistemological beliefs, a questionnaire for epistemological belief was adapted from Schommer (1990) and divided into four subscales for structure or simplicity of knowledge, certain aspects of knowledge, control of learning, and speed of learning.The questionnaire constructed by Schommer is regularly used in studies on epistemological beliefs. Most studies related to epistemological beliefs refer to Schommers questionnaire as being a valid, well-known and widely used research instrument (Clarebout, Elen, Luyten, & Bamps, 2001). In addition, epistemological beliefs can be domain general which means they apply across all domains. Schommers questionnaire was found to be valid in most domains including education (Schommer-Aikins, & Duell, 2013).

4. Result

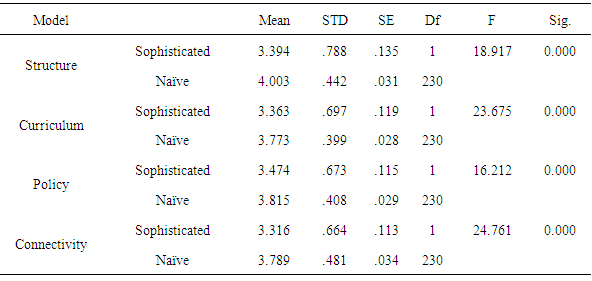

- This study examined the significant differences in e-Learning experiences with respect to i) structure, ii) curriculum, iii) policy, and iv) connectivity between students with naïve and sophisticated beliefs. Table 1 reports the mean, SD, and results of ANOVA for E-Learning Experience by EB. The categorizing of epistemological beliefs was based on the mean score obtained from the respondents. Responses with mean <3.5 were labeled as sophisticated, and >3.5 were labeled as naïve. This assumption was driven from Schommer (1990). For H01 i) structure, the naïve group reported a mean of 4.00 with SD of 0.44 while the sophisticated group reported a mean of 3.39 with SD of 0.78. Results of ANOVA showed that F (1, 230) = 18.91 at p=0.000. The findings indicated that students with naïve beliefs were more appreciative of the structure of e-Learning facilities provided by LHEIs than the students with sophisticated beliefs.

|

|

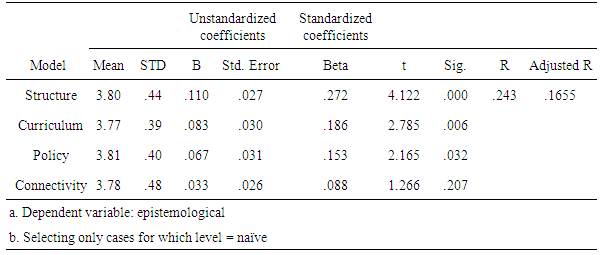

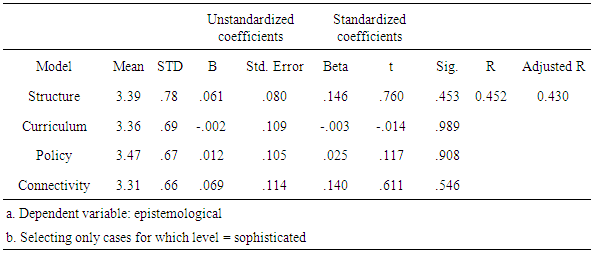

- For i) structure, students with naïve belief found that the current structure of e-Learning affects their epistemological belief to learn (ß=0.27, t=4.12, p=0.000). For ii) curriculum, the result demonstrated that the students found the current curriculum affects the way they learn in e-Learning (ß=0.18, t=2.78, p=0.006). For iii) policy, students with naïve belief found that the current policy effects their epistemological belief to learn in e-Learning (ß=0.15, t=2.16, p=0.032) provided by the LHEIs. The average correlation between the variables was 0.24, which is considered acceptable. However, the adjusted R value of 16% explained the variance in the scores for the students’ epistemological belief based on the current e-Learning structure, curriculum, policy, and connectivity. These findings indicated that structure, curriculum and policy significantly influenced naïve beliefs whereas connectivity had no significant effect on students with naïve beliefs.We examined the significant effects of e-Learning experiences with respect to i) structure, ii) curriculum, iii) policy, and iv) connectivity on sophisticated beliefs. Table 3 presents the regression effects of e-Learning experience on sophisticated beliefs. For i) structure, students with sophisticated belief did not find that the current structure of e-Learning affects their epistemological belief to learn (ß=0.14, t=0.76, p=0.453). For ii) curriculum, the result showed that students found the current curriculum to have an effect on the manner in which they learn through e-Learning (ß=–0.03, t=–0.14, p=0.989). For iii) policy, students with sophisticated beliefs did not find that the current policy provided by the LHEIs affects their epistemological belief to learn in e-Learning (ß=0.025, t=0.117, p=0.908). The same is true for iv) connectivity, where the majority of students with sophisticated beliefs did not find connectivity affects their learning (ß=0.14, t=0.61, p=0.546). These findings indicated that structure, curriculum, policy, and connectivity had no significant effect on students with sophisticated beliefs to use e-Learning. This result suggests that LHEIs should consider providing more effective techniques to meet the learning demands of students with sophisticated beliefs.

|

5. Discussion

- The findings in this study in the context of LHEIs showed that students with naïve beliefs agreed that structure, curriculum, policy, and connectivity of the e-Learning are the main factors that perceive their epistemological view about the use and adoption of technological means. However, the opinions of the students with sophisticated beliefs were the opposite. The students with naïve beliefs appreciated all the facilities with which they were provided and saw no need to upgrade because they felt they were in a position to adapt. However, the research established that the students with naïve beliefs were concerned with accessing and using e-Learning. This can be reasoned to that fact that structure of e-learning is consider an important aspect for self-directed learning (Chen, 2009), therefore, students epistemic beliefs to use e-Learning is relevant to the context of this study whereas naïve students were found to be more likely to influence, how e-Learning opportunities are used for meeting individual learning demands. The result showed that structure of the organization to be associated with students with naïve belief in which individual conviction of knowing and learning determines learning strategies and learning purposes necessary for using e-Learning. This finding was found to enrich Limon’s (2004) claims who highlighted the possible influence of environmental settings in changing one’s epistemic beliefs. It also argues with other prior studies like Jehng, Johnson and Anderson (1993) who stated the influence of space on forming or shaping individual’s epistemic beliefs based on the constitute of school and its resources. Others like Trautwein and Lüdtke (2007) demonstrated that epistemological beliefs become sophisticated as students advance through educational levels (Jehng, et al., 1993; King & Magun-Jackson, 2010; Palmer and Marra 2004; Paulsen & Wells, 1998; King and Magun-Jackson (2009); Schommer, 1993 and Wise, et al., 2004). This sends an alert to LHEIs and instructors at Libyan universities to examine seriously the possible aspects related to naïve thinking, as 80% of students were found to have naïve thinking. In addition, King and Magun-Jackson (2009) report that learners with less sophisticated epistemological beliefs need to be assisted through new learning methodologies developed by both educators and teachers.

6. Conclusions

- It was concluded that Libyan students with sophisticated beliefs had contrasting perceptions in that they believe that their current e-Learning experience does not promote the development of their self-regulated learning and motivation. In addition, the findings assessed that epistemological beliefs in terms of sophisticated belief do not influence the LHEIs perception towards the use of e-Learning services and to develop in return their self-regulated learning and motivation. As such, this study has the potential to provide a clear view about the current belief student may process towards e-Learning settings in the Libyan context.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML