-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(2): 183-188

doi:10.5923/c.economics.201501.22

Empirical Studies: Corruption and Economic Growth

Chiam Chooi Chea

OUM Business School, Open University Malaysia

Correspondence to: Chiam Chooi Chea, OUM Business School, Open University Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Corruption has been one of the most perceived despicable actions and it has been around for a very long time and will be around in the future unless governments can figure out effective ways to combat it. Although the study of the causes and consequences of corruption has a long history in economics, however, corruption itself is clandestine. This study is an empirical discussion paper that highlights the negative and positive perspectives of corruption to an economy’s growth using past studies. This paper shed lights on the positive side of corruption despite the norm of negative effects of corruption to economic growth for a country because not all researchers agree that the development of a country can only be achieved through policies of an uncorrupted government and bureaucracy.

Keywords: Corruption, Growth, Allocation of resources

Cite this paper: Chiam Chooi Chea, Empirical Studies: Corruption and Economic Growth, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 183-188. doi: 10.5923/c.economics.201501.22.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Corruption is defined as dishonest or illegal behavior, especially of people in authority (Oxford Dictionary). Corruption and bribery are complex transactions that involve both someone who offers a benefit, often a bribe, and someone who accepts, as well as a variety of specialists or intermediaries to facilitate the transaction (Transparency International, 2013). Corruption in the context of economic is often defined as the use of public property for personal gain. Market resolves a problem through the emergence of middlemen who receives commissions for bringing all the relevant layers of officials together to obtain their approval simultaneously.Corruption has been around for a very long time and will be around in the future unless governments can figure out effective ways to combat it. Although the study of the causes and consequences of corruption has a long history in economics, however, corruption itself is clandestine. As a consequence, corruption is notoriously hard to measure and empirical economic research on the question is largely meager. Corruption can be explained through the relationship of principal-agent. Principal is the general public, while agent includes the public officials or government employees. An agent is responsible to maximize the profit or gain on behalf of its principal, while the principal rewards its agent for performing its obligation. The agent (public officials and government employees) is said to fail to look after the interest of the principal (public) when agent misuses the authority given by the principal for private gain or interest. The act of the agent in this case is classified as an act of corruption in which the agent is dishonest in performing its responsibility for its personal interest. The outcome of corruption is often associated with misallocation of resources and inefficiency. Evidence of bureaucratic corruption exists in all societies, at all stages of economic development, and under different political and economic regimes. In 1995, transparency international has published an annual corruption perception index (CPI) ordering the countries of the world according to “the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians”. Meanwhile, the organisation states that the corruption as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. There have been many studies on this field and most of these studies show a significant negative relationship between corruption and various measures of economic welfare, including per capita income, income equality and economic growth. However, there are several findings showed positive impact of corruption in economic growth, with certain conditions imposed (e.g. the degree of economic freedom etc.).Corruption can be harmful and unhealthy to the whole economic system. The effects of this unhealthy phenomenon involve misallocations of resources and inefficiency in the economy. Corruption not only raises the cost of production but also reduces the quality of productivity of resources. The cost of production may be unbearable for producers and consumers may choose not to consume the product. The demand for that particular good may drops. This may directly or indirectly slows the economic growth as a whole because these resources could have been utilized and benefited the public, if they were otherwise being efficiently allocated. Corruption influenced the growth of an economy through reductions in the quality of production of goods. Goods that are low in quality are typically less demanded and may lessen the flow of the goods in the market. The economy cycle is impeded and hence, affected the growth rate of an economy. The investment level of an economy may decreases as well, in both physical and human capital due to the influence of corruption. It is assumed that a license must be obtained before a new good can be produced and sold. Corruption works as a tax to firms where firms are required to pay extra charges in order to produce its product. Firm that fails to pay “extra charges” to the government officials may have its license of newly invented goods restricted in several ways (e.g. denying permission or delaying its release). Firms may reduce the investment in physical capital because of low incentive for firm to invest in innovating or designing new goods in the economy. It would not do any good to the profit of the firm and the economic growth. Investment in human capital may decrease with an increase in the level of corruption as well. Corruption reduces economic growth through a negative influence on investments in human capital.This write-up aims to provide a theoretical review of corruption on economic growth. The organization of the report is as follow: In Section 2.0, theoretical relationships between these two variables are discussed. Then, in Section 3.0, selected empirical evidence based on previous study will be ruled. Lastly, the conclusion follows in the Section 4.0.

2. Theoretical Background

- A substantial literature has been developed over the past few years examining the sources and consequences of corruption. A wide array of variables has been linked to corruption. In recent years, a large number of papers related to corruption and economic growth have been produced.

2.1. Negative Perspective

- Corruption embarks in all countries, irrespective of whether they are rich or poor, dictatorships or democracies, socialist or capitalist (Lui, 1996). Bulks of literatures relate the impact of corruption on economic performance. However, previous studies have not drawn a consensus view about the effect of corruption on economic growth. Some researchers suggest that corruption might be desirable but some are not. Basically, the corruption is thwarted by the efforts of grafters and this is hostile to development. Mo (2001) noticed that, the demand for import quotas and permits from government is highly inelastic. Hence, this may be one of the sources of corruption likely outbreaks. Lui (1996) identifies salient characteristics of corruption in three aspects: (1) It is a rent-seeking activity induced by deviation from the perfectly competitive market (market imperfections) caused by government regulations or interference; (2) It is illegal and (3) Investment in socially unproductive human capital (political capital). Corruption tends to hurt innovative activities because innovators need government-supplied goods (eg. import quotas and permit) through offer bribe. Corruption by itself does not incur much social cost. The potential pitfall is the allocation of capital, technology and talent from their most productive uses through corruption especially in influencing the government’s choice of project. Resources may be shifted away from productive activities (education and health care) to potentially useless projects (defense) if maintaining secrecy in latter is easier (Shleifer and Vishny, 1993). Lui (1996) argue that the endogenous growth models where productive human capital or physical capital are driving forces, diverting resources to non-productive political capital will lowers the economy’s long-term growth rate. Society is better off if the level of this investment (political capital) is lower. Knack and Keefer (1997) also examine the effects of different institutional variables on growth, with results that tend to support the hypothesis that corruption negatively affects economic growth, with an indirect effect through investment. A similar finding has reinforced by Pellegrini and Gerlagh (2004) study. This hypothesis is consistent with the empirical findings of Mauro (1995) where the corruption and economic growth are negatively related. However, the micro’s findings (firm level) are mismatch with the macro evidence in which the impacts of corruption on economic growth still inconclusive.

2.2. Positive Perspective

- Most of the literatures link the corruption to slower the economic growth. Who condemns corruption? Surprisingly not all researchers condemn corruption. Leff (1964) does not agree that the development can only be best proceed through the policies of an uncorrupted government and bureaucracy. Leff (1964) therefore, has proposed some alleged negative effects of corruption such as impeding of taxation, usefulness of government spending, and cynicism as argued in the economic development literatures. If the government consists of traditional elite which is indifferent if not hostile to development, the propensity for investment and economic innovation may be higher outside the government than within it. Hence, Leff (1964) argued that there are six positive effects of corruption: (1) Indifferences and hostility of government, (2) governments have other priorities, (3) uncertainty reduces and increases investment, (4) innovation, (5) competition and efficiency, and (6) as a hedge against bad policy. Although some studies critique the arguments by Leff (1964) are actually misunderstood, but why public policy will fail has illustrated as indirect way. Huntington (1968), the proponents of “efficient corruption” claim that bribery may allow firms to get things done in an economy plagued by bureaucratic hold-ups. Corruption erodes the monopoly position of the dictator, hence corruption will not exist if the resource allocation system is perfectly competitive because public have no incentive to pay official extra money. Innovative process will improve implicitly. In addition, corruption also can act as a lubricant that smoothes operations and, hence, raises the efficiency of an economy (Mo, 2001). In addition, Lui (1996) argued the bribes sometimes can partially restore the price mechanism and improve allocative efficiency. Corruption has some beneficial effects to society. Free market system therefore may uproot their profit-making opportunities will resist economic reforms. One remaining enigmatic question is “Why is it that countries with high levels of corruption have high growth, while others do not?” For example, China has been able to grow fast while being ranked among the most corrupt countries (80 of 175 by 2013 CPI score). Teles (2007) found that if a country has only a lot of judicial or bureaucratic corruption it may lead to growth at high rates, but when these two kinds of corruptions occur at the same time, then the economy will be at a low-growth pitfall. Braguinsky (1996) proposes the corruption in capitalist is a transitive but will detriment economic growth in totalitarian environment. Hence, the differential effect such as country characteristics and type of corruption are important areas for research.

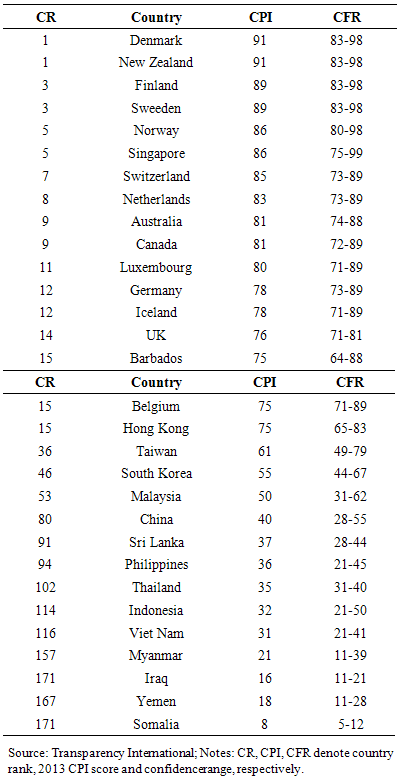

2.3. Measuring Corruption

- There are wide range of corruption indicators used as proxies in the previous literatures such as Business International Index, International Country Risk Guide Index, Global Competitiveness Report Index and Transparency International Indices. Since 1995, Transparency International has published an annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ordering the countries of the world according to the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians. Mo (2001) found bureaucratic red tape and weak legislative and judicial system may be alleviated by Gastil political rights index and initial per capita income as a set of institutional problem. However, Mo (2001) argued that measure of corruption level obtained from Transparency International is more compelling if compare with other index as proxies. The CPI ranks 180 countries by their perceived levels of corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys. The index ranges from 0 to 10, with 10 indicating a highly clean country and 0 indicating a highly corrupt country. In other words, a higher score means less (perceived) corruption. Table 1 shows 2013 CPI score for selected 30 countries. It notes that Denmark, New Zealand and Sweden as top three in the list and followed by Singapore, Switzerland, Netherlands, Australia, Canada as the top CPI score. Bribe Payers Index (BPI) evaluates the supply side of corruption as the likelihood of firms from the world’s industrialized countries to bribe abroad. BPI is a ranking of twenty-two of the world’s most economically influential countries according to the likelihood of their firms to bribe abroad. The countries are selected based on their foreign direct investment inflows and imports, and importance in regional trade. The scores range from 0 to 10, indicating the likelihood of firms headquartered in these countries to bribe when operating abroad: the higher the score for a country, the lower the likelihood of companies from this country to engage in bribery when doing business abroad. Some of the information such as Bribe Payers Index 203 can be seen in Table 1. Nonetheless, the rankings of countries as more or less corrupt are based on subjective judgments and as such the reliability of data plays an important role in quantify the magnitude of corruption used in the analysis.

|

3. Empirical Discussions

- Mauro (1995) investigated the relationship between investment and corruption for 58 countries. By utilizing the corruption indicators from 1980 to 1983 from Business International (1984), Mauro found corruption is deleterious for economic growth. In order to identify the channels through which corruption affects the economic growth, Mo (2001) extends the analysis by estimating the impact of investment, human capital, and political stability channel in the transmission process and the rate of productivity growth on level of corruption, initial GDP per capital and human capital stock on economic performance. Mauro (1995) found a 1 percent increase in the corruption level reduces the growth rate by about 0.72 percent after controlling for the level of per capita real GDP. In addition, political instability channel is the most important channel through which corruption affects economic performance. This finding is consistent with the survey done by Transparency International Bribe Payers in 2008 where political parties severely affected by corruption. In 1999, a study by Enrlich and Lui (1999) studied a link between corruption, government and growth. This paper attempts to fill the void through equilibrium models of endogenous growth. In this paper, a “balanced growth” is derived as a balancing act between accumulating human capital, which engenders growth. It found that the relationship between corruption and the economy is explained as endogenous outcome of competition between growth-enhancing and socially unproductive investments and its reaction to exogenous factors. Other than that, the relationship between government, corruption, and the economy’s growth is nonlinear. It is because government intervention in private economic activity hurts most in the poorest countries and those at a critical takeoff level.A study by Rivera-Batiz (2001) examines the effects of capital account liberalization on the long-run growth of a developing economy. It uses a general-equilibrium and the construction of an endogenous growth model which corruption forms an integral part of governance system of the country. A drop in growth is obtained when the level of corruption is high enough to cause domestic rates of return to capital before liberalization to drop below those in the rest of the world. On the other hand, if the level of corruption is sufficiently low, the capital account liberalization will serve as a boost to the country’s technical change and growth.Del Monte and Papagni (2001) in their research maintain that corruption arises from purchases made by government officials. This study uses dynamic panel data approach to economic growth based on time series (1963-1991) for 20 Italian regions. This study focuses on the determinants of the rate of growth, corruption, public infrastructures and public expenditures. The results show two distinct negative effects of corruption on economic growth. One effect seems to be that on private investment; the other is on the efficiency of expenditures on public investments. According to them, corruption has a direct negative effect on the long run opportunities of economic growth because governments can offer fewer inputs to private economic activities. With a positive amount of corrupt transactions, some economic resources are wasted and fewer infrastructure or public services are disposable for private production. According to Gyimah-Brempong (2002), a study conducted in 21 Africa countries from 1993 to 1999, indicated that corruption decreases economic growth directly and indirectly through decreased investment in physical capital. According to empirical evidence, a unit increase in corruption decreases growth rates of GDP by 0.75 and 0.9 percentage points and per capita income reduces between 0.29 and 0.41 percentage points per year. According to the studies, corruption decreases growth directly through decreased productivity and misallocation of existing resources. In result, corruption hurts the poor more than the rich on African countries. Pellegrini and Gerlagh (2004) studied empirically the direct and indirect transmission channels through which corruption affects growth levels. It focuses on the effect of corruption on investment, schooling, trade policy and political stability and studies the contributions of various channels to the effect of growth. This paper uses basis cross-country regressions with estimates of the direct effect of corruption. It also uses instrumentals variables for corruption and robustness checks and confirmed a negative effect of corruption on growth. One standard deviation increase in the corruption index is associated with a decrease in investments of 2.46 percentage points, which in turn will decrease economic growth by 0.34 percent per year. When the transmission channel is “openness”, a standard deviation increase in the corruption index is associated with a decrease of the openness index by 0.19, resulting a decrease in economic growth by 0.30 percent per year. In this study also found that the transmission channels explain 81 percent of the effect of corruption on growth.Teles (2007) relates bureaucratic corruption to economic growth where agents have a choice of two assets in which to invest: human capital (productive and without risk) and political capital (non-productive and risky). Political capital obtained income from bureaucratic corruption which has no direct effect upon production (redistributive effect). Teles suggested a new approach to the transition mechanism between democracy and growth where the more democratic regimes will imply lower rates of corruption and higher rates of growth. Teles found the more political capital is accumulated, less human capital is accumulated are limiting the economy’s capacity for growth. Rano and Akanni (2009) did a study to investigate the impact of corruption on economic growth in Nigeria from 1986-2007. Barro-type endogenous growth model was used to estimate the relationship between government capital expenditure, human capital development and total employment. The study found that corruption exerts negative effect on economic growth where about 20% of the increase in government capital expenditure ends up in private pockets. However, the study also found that corruption exerts positive effect of corruption on capital expenditure. Overall, this paper discovers that corruption exerts both direct and indirect negative effects one economic growth in Nigeria. Granger causality links between foreign direct investments and financial markets for a panel of 22 developing countries over the period of 1976-2003, Kholdy and Sohrabian (2008) found foreign direct investment may jump-start financial development in developing countries and most of the causal links are found in developing countries which experience a higher level of corruption in the form of excessive patronage, nepotism, job reservation, ‘favor-for-favors, secret party funding and suspiciously close ties between politics and business.Nevertheless, Swaleheen and Stansel (2007) argued that in countries with low economic freedom, corruption appears to reduce economic growth. This study uses cross sectional analyses in a panel of 60 countries, countries with low economic freedom, corruption reduces economic growth. Economic freedom in this context is where individuals limited economic choices. In this study, economic freedom is included explicitly as an explanatory variable. Next, corruption and investment are treated as endogenous variables. The findings of this paper differs with the generally established result that corruption decreases economic growth. They added that, all things being equal, corruption lowers growth when the economic agents have very few choices (economic freedom is low), but if people face many choices (economic freedom is high), corruption helps growth by providing a way around government controls. The empirical study in this paper shows that, in economies where economic freedom is high, if bribing makes public officials lees diligent in enforcing restrictions on firms’ activities, output will increase. However, corruption will restrict output when bribes reduce competition and increase market rigidities. Thus, this outcome is more likely happens in countries where freedom is low due to the widespread state owner of assets (eg. in China), monopolies and high tariff barriers granted to businesses owned by ruling elites and their cronies (eg. Philippines under Marcos and Indonesia under Suharto), and state-run marketing boards that are often the sole purchasers of agricultural products (eg. in several African countries).

4. Summary

- From the theoretical background and empirical evidence from various studies spread in various countries in the world using different methods over the years, there are mostly negative findings of corruption on economic growth. Nevertheless, there are also positive findings found on the effects of corruption on economic growth. That is, studies by Swaleheen and Stansel (2007) and Braguinsky (1996) as what proposed by Leff (1986) and Huntington (1968). Direct or indirect transmission channels are tested extensively by researchers over the years on the effects of corruption on economic growth. Corruption occurs at all levels of society, from local and national governments, civil society, judiciary functions, large and small businesses (firm level), military and other services and so on. Most studies showed that corruption affects the poorest the most, whether in rich or poor nations. The issue of corruption is very much inter-related with other issues. Other prospect areas to be further studies on is the economic system within a country itself that has shaped the current form of globalization in the past decades requires further scrutiny for it has also created conditions whereby corruption can flourish. It is hard to see this formal corruption, even legal forms of “corruption.” It is relatively easy to assume that these are not even issues because they are part of the laws and institutions that govern national and international communities and many of us will be accustomed to how the way it works.Overall, corruption is illegal. Indeed, Chinese believe that in matters of corruption, it is useless to “hit the houseflies, but not the tigers”. Therefore, the network or what is known as guanxi may collapse once the patriarch disappears (Lui, 1996). Del Monte and Papagni (2001) have suggested policies are necessary to deter corruption and to increase the efficiency of local public institutions that could give very positive impulses to economic growth. Despite many officials are convicted and a lot of corruption networks are crippled but institution (eg. ICAC [Hong Kong]) or policies (eg. to increase wage and competition, and anti-corruption programs) which fight against crime and corruption still play a crucial role for maintenance purposes. Unless government is really determined to fight corruption at all levels, this issue is going to be around forever and the economic system in the country will continue to collapse. And it definitely will not benefit the public and country as a whole. In addition, liberalization may be one of the effective tools to reduce corruption as suggested by Lui (1996).All in all, the net effect of corruption on economic growth still remained enigmatic. Basically, the impact of corruption pretty much depends on the characteristic of a country (e.g. economic freedom, financial structure, government expenditure and etc) and types of corruption in which some countries with high levels of corruption have high growth, while others do not. In addition, the methodology and/or data utilized in the analysis may also be one of the factors contributed to this puzzle and the mismatch between macro and micro level evidences.This paper can be further researched using quantitative analysis to support the positive and negative effects alleged by the past studies. This study shed lights on the positive side of corruption because not all past studies agreed that the development of a country can be achieved through policies of an uncorrupted government and bureaucracy.

Note

- 1. Jain (2001) for instance has provided an excellent review of corruption.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML