-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(2): 139-147

doi:10.5923/c.economics.201501.15

Public Versus Private Payment for Financing Higher Education

Hieng Soon Lau

University College of Technology Sarawak

Correspondence to: Hieng Soon Lau, University College of Technology Sarawak.

Email: hiengsoonlau@ucts.edu.my

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper argues on public versus private payment for higher education with reference to loans and grant/scholarship. The author critically evaluate reasons which are consumer ignorance, economies of scale, externalities and the public good and imperfections in the capital and insurance markets for market failure. Among four reasons, only externalities and the public good and imperfections in the capital and insurance markets may provide support for the state’s subsidies to higher education but do not cause it. Hence, the debate about public versus private payment for higher education depends mainly on political decisions rather than on efficiency arguments. However, both politicians and economists would ask the same question: “To what extent higher education should be subsidised?” though their criteria may differ. The author examines the cost-effectiveness, exchange efficiency and financial efficiency to suggest which option of subsidy, loan or scholarships is better.

Keywords: Loans, Grants/scholarships, Cost-Effectiveness, Financial efficiency, Consumer ignorance, Externalities, Economies of scales

Cite this paper: Hieng Soon Lau, Public Versus Private Payment for Financing Higher Education, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 139-147. doi: 10.5923/c.economics.201501.15.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- As higher education policy shifts from supporting elitist to mass participation, governments globally are facing budgetary constraints. This raises the debate on who should and how to pay for higher education? Some argue that “he who benefits from the education should pay for it”. Others propose that the state should pay, since education can be regarded as a “public good”. Society and taxpayer should also contribute since higher education would benefit both the individuals and society as a whole. Many countries therefore have introduced cost-recovery methods such as loan schemes to raise funds from participating students. Thus, higher education institutions may regard students as consumers, while students may see university education as an investment, rewarded with future high monetary and non-monetary benefits (Wilson, 1996). The aim of this paper is to critically analyse the argument on the public versus private payment for higher education. There have been arguments on the balance between public and private finance of higher education and the role which government should play. In the context of education, Le Grand (1989) argues that the quantity provided, its form, and (with some reservations) the people who receive it will be determined best by a free market. This is mainly because in a market system, consumers are able to express their preferences when they make decisions about the type and quantity of education they purchase. Through the expression of these individual choices, the socially efficient quantity of each type of education will be indicated. Hence, the required education will be made available. Educational institutions will be competing for students (as these will be the source of their income) and will respond by offering those types of education that are in demand. However, the market may not operate in this way. There are specific failings that may prevent the market in education from operating efficiently, and which account for the state's interference by subsidising higher education. Market failure may occur because consumers have inadequate information or are unable to interpret it. Market failure also occurs because of technical economies of scale, externalities in production and/or consumption, and inherent imperfections in capital and insurance markets. We analyse these conditions to examine whether they are likely to apply in higher education, and whether they may provide a case for government interventions in higher education as against private provision.

1.1. Consumer Ignorance

- In market economics, it is considered axiomatic that the consumer knows his/her interest better than anyone else. In the case of higher education, Barr (1989) argues that students are an intelligent and fairly “street-wise” consumer group. Students have time to acquire the information that they need and time for seeking advice. The information is sufficiently simple for the student to understand it, and to a large extent, evaluate it. The provision of advisory and counselling services independent of schools and colleges would enable students to make better-informed decisions. Parents may also give advice to their children in making decision of attending higher education. However, in some cases parents may not act in their children’s interests, because of malevolence or simply lack of information (Le Grand, 1989). Hence, Le Grand (1989) claims that some form of intervention will be necessary because of lack of parental judgement. Clive (2000) also argued that the demand for education, is somehow different from the demand of other goods as individuals may not realise the benefits of education until it is “too late”. Government may embody past wisdom about the benefits of education and so may have a role in reducing this uncertainty and ignorance (Clive, 2000, p 164). However, this may not be true since in a free market, institutions will disseminate information more effectively as they compete for students. Barr (1989) also argues that students can make better choices than central planners concerning the needs of economy. Evidence (Moser and Layard, 1964; Blaug, 1970; Layard, 1972) has shown the difficulty of trying to project the UK’s medium-term manpower needs in the Robbins Report (UK, 1963) as cited by (Barr, 1989). However, government should have a right to view about and influence over the direction of higher education (Barr, 1989). It is unlikely for consumer ignorance to prevail among 18-year-olds making decisions whether to undertake higher education courses. Empirical evidence from studies in the UK, the USA and Pakistan show that 16-18-year-olds are well informed about the effect of schooling on their labour market prospects (Freeman, 1981; Williams and Gordon, 1981). I would say that consumer ignorance cannot be a general condition causing failure in higher education market in this cyber age when information is accessible freely and quickly.

1.2. Economies of Scale

- Many studies have shown that there are economies of scale in education (Cohn, 1979). Unit cost will fall when more students enrol until the university reaches the optimal point. These economies exist in conventional universities and even more so in distance-educational establishments such as the Open University (Wagner, 1977; Mace, 1987). Thus, prima facie, if there has been an inadequate number of students enrolling, subsidies should be provided so as to encourage enrolments to rise to adequate numbers thereby securing these potential economies of scale. Economies of scale may cause market failure as the average cost has not reached its lowest point, and the production is not at an optimal level.However, the evidence is at best ambivalent. In any case, it is surely a management issue to ensure that courses are organised so as to obtain the maximum benefits from economies of scale. Moreover, differences in unit costs of education seem not to be clearly related to its financial resources, though there is evidence of economies of scale (Psacharopoulos and Woodhall, 1985). Economies of scale do not solely depend on student enrolments but also on other factors such as student-staff ratio, quality of staff, costs of capital and equipment and cost of different subjects. Moreover, Monk (1990) also argues that educational production may not be characterised by economies of scale whereby the unit cost declines as size increases.Therefore, economies of scale do not provide a general reason for government intervention in higher education, because we cannot assume that universities or colleges are always and everywhere suboptimal in size. Levels of enrolment can be dealt with case by case and hence are not a matter of general principle (Mace, 1987). Thus, to consider economies of scale is a management issue, not a rationale for the public subsidy of higher education.

1.3. Externalities and the Public Good

- Another economic justification for public subsidies to higher education is based on externalities, meaning the benefits of higher education which do not accrue to individual graduates (Blaug, 1990). As Mace (1987) defines them, “Externalities in higher education occur when the productivity and/or psychic satisfaction of person A has been altered solely as a result of the higher education of B”. (Mace, 1987, p7). However, externalities can be positive (A’s productivity and /or satisfaction rises), or negative (A’s productivity and/or satisfaction falls). The presence of these externalities in the market would violate the necessary conditions for Pareto optimality. Externalities could also be represented as a continuum. At one end of the continuum there are no externalities, meaning that the market reflects the full value of the services provided. This is the case of private good. At the other extreme, externalities are the only benefits or losses from the activity in question. This is the case of public good or public bad. The national defence service is a good example of a public good where consumption is necessarily joint and equal, and no one's enjoyment of the service is affected by anyone else’s. Thus, the good will not be provided by the market because no individual is prepared to pay for the service. It must therefore be provided by the state, if it is to be provided at all. However, critics may question the provision of private security services which may also bring “spill-over” benefits to those who do not pay for them. Nevertheless, the provision of private security services differs from the provision of national defence because the former is limited whereas the latter covers the whole nation. Moreover, anyone who employs a private security service bears no responsibilities to those who enjoy the “spill-over” benefits. However, no one has succeeded in quantifying the exact external benefits of higher education (Blaug, 1990; Seville and Tooley, 1997) and there is no simple answer as to how much subsidy should be provided to ensure optimal investment in higher education (Mace, 1987). Also, the free-riding problem may also change over time (Monk, 1990).Literature reporting research on externalities in higher education shows mixed results. Studies by Barro and Sala-I-Martin (1995), Nehru et al. (1994) and Gemmell (1996), have shown that education has a positive effect on growth rates. However, the studies of Oulton and Young (1996), and (Pritchett (1995) show that some basic educational measures often appear to be uncorrelated with growth, which may be due to the absence of measures of educational quality (Dearing Report, 1997). Moreover, though there is some evidence that higher education affects income growth positively, a number of studies have failed to find such a connection. Milton Friedman (1980) argued that the external benefits of American higher education are negligibly small. In contrast, Marris (1983) argued that externalities are very large in higher education, amounting to 25 per cent of the graduate’s indirect cost. Jenkins (1995a, b) is able to draw some tentative conclusions on the extent of externalities to higher education for the UK and some other developed countries. His “macro” estimates of rates of return to a higher education qualification for UK are between 26-86%. Generally, evidence on the extent of externalities is derived from fairly crude and unreliable methodologies (Dearing Report, 1997). The issue of externalities in education could become even more complex when related to educational finance. We should know the marginal addition to external benefits, not the total externalities of education (Mace, 1987). The state should have the knowledge of how externalities are associated with the extra (marginal) students that would enter universities because of state subsidy. The existence of externalities may provide a genuine reason for subsidising higher education, though it does not provide any guidance about the size of subsidy. The real question is not how large the subsidies should be but how they vary with the volume of enrolments. Blaug (1990) also argues that in the absence of measurement, it is uncertain that the net sum of positive and negative externalities is in fact positive. Externalities may be negative (Williams, 1999). Thus, the economic case for subsidising higher education is at best weak and at worst non-existent (Blaug, 1990). Consequently, the present universal system of public support for higher education in Malaysia is not to be explained by the alleged external effects of higher education but rather as a political decision, which may change in the long run. Therefore, I agree with Blaug (1990) that “…..it is electoral support for policies deemed to be fair and just in creating equality in educational opportunities that accounts for the particular mix of subsidies that one actually observes in different countries." (Blaug, 1990, p16). This suggests that there is a trade-off between efficiency and equity arguments regarding the public subsidy for higher education because matters of equity are left to political scientists, not economists. The political economy plays an important part in determining the public subsidy for the funding of higher education. In the Malaysian case, financial policies affecting students may be politically driven in line with the quota system embedded in the New Economic Policy and National Development Policy. Higher education experienced a painful adjustment during the NEP whereby a quota system was introduced favouring the native student intake and staff recruitment in higher education, so that natives should catch up with other groups in socio-economic arenas (Lim, 1993, p21). Natives gained favourable opportunities in higher education by means of special financial support, the mandated use of Malay as the language of instruction, and preferential access to universities and colleges. This policy was diluted when the NEP ended. On the other hand, we can also say that societies have an interest in equity not only as an ideological principle, but also from an efficiency standpoint. The higher education system is most efficient when access is determined by ability to achieve, not ability to pay. Hence, public intervention is justified to the extent of ensuring that qualified, poor individuals, who in most cases have no access to credit and who cannot afford to forgo income while attending school, have access to education (Carlson, 1992).

1.4. Imperfections in the Capital and Insurance Markets

- It is claimed that in a non-slave market one usually cannot borrow in the capital market to finance investment in human capital. We cannot offer ourselves as collateral to a bank to secure a loan on our own education (Blaug, 1990). Commercial banks are usually unwilling to finance the personal cost of higher education, even at excessive rates of interests. However, this view may not hold true since contracts can be signed between the lender and the borrower. Nearly all MBA students, for example, are privately funded because the banks highly value the potential of MBA holders to repay the loans. Commercial banks in the UK are also willing to give education loans to graduates and undergraduates, but at excessive rates of interest causing student debts to leap by 17.5% in 1999 (The Times, April 22 2000).To summarise, the externalities and imperfections in the capital and insurance markets may provide support for the state's subsidies to higher education but do not cause it. It is political decisions through electoral processes that are responsible to provide the subsidies to higher education. Hence, the debate about public versus private payment for higher education depends mainly on political decisions rather than on efficiency arguments. However, both politicians and economists would ask the same question: “To what extent higher education should be subsidised?” though their criteria may differ. I take the position that higher education is a “quasi” public good. If higher education is to be subsidised directly to students, which option is better, loans or scholarships?

2. Student Loans or Grants

- In the literature, much has been said about student loans and grants, considered conceptually and empirically. The theoretical arguments which underpin the debate on loans or grants relate to efficiency and equity aspects. This article argues with three criteria of efficiency: cost-effectiveness, exchange efficiency and financial efficiency.

2.1. Cost-Effectiveness

- Cost-effectiveness refers to whether investments in education, through provision of loans and scholarships, have achieved the objectives as desired by the funding bodies, that is, whether recipients graduated with good grades and on time so as to minimise costs. Costs refer to loan and scholarship disbursements and output refers to undergraduates successfully graduating from universities. Scholarship or loan would be very cost-effective if students graduated on time. Thus, cost-effectiveness relates to economic efficiency, that is achieving a desired level of output at minimum cost (Psacharopoulos and Woodhall, 1985, p 206). Related to this type of efficiency are students’ attitudes towards studies. According to Woodhall (1970), advocates of loans claim that students would use their time more efficiently once loans are given because they need to pay for the costs of higher education. However, opponents of loans argue that the need to repay loans causes financial problems and worries among students, leading to wastage if students withdraw from studies; whereas a grant system encourages the student to spend time efficiently in devoting himself /herself to study without financial worries. Whether students actually work harder under different systems is difficult to answer since the question is partly subjective, and the answer would vary according to the details of the structure and curriculum of higher education (Woodhall, 1970). Moreover, it also depends on the types of loans which students use. Income-contingent loans, which require students to pay a proportion of their incomes after graduation, may not cause financial worries among students. On the other hand, the mortgage type of loans, which require repayments in equal instalments, may add burdens and worries to students. Students worry because there is a risk of failure in their studies or of being unemployed and therefore unable to repay the debts. Students may be motivated to study harder if loans can be converted into grants wholly or partially, depending on their final results.

2.2. Efficiency in Meeting the Manpower Needs

- Efficiency in meeting the Manpower Needs refers to the aspect of economic efficiency which examines whether the output (graduates) meet the demand of the society. This is a narrow version of efficiency which examines the extent to which tertiary education meets manpower and employment needs. The investment in human capital through provisions of loans and scholarships would be efficient if output (graduates) is produced on time to meet the forecast manpower needs of the economy.This type of efficiency could also relate to the “recruitment effect” of the loan and scholarship systems, motivating recipients to enter or continue studies in university, who otherwise would not attend or dropout if not given such financial support. The extent to which loans and scholarships are used for recruiting qualified persons into attending university education shows how far they bring the potential manpower into the economy, which would otherwise be lost because of financial constraints, and thus suggests its contribution to the efficiency. Comparison of impacts may contribute to the debate on loans versus grants.

2.3. The Financial Efficiency

- The financial efficiency of loans can be defined as the recovery ratio- the extent to which the loan is repaid in full (Albrecht & Ziderman, 1991). Comparing government lending to students and what is returned in repayments would indicate the loan efficiency. It also indicates whether the loans can be fully self-revolving in a restrictive sense. It also depends on the cost of administration, the defaults, interest subsidy, rate of repayment, and grace period. Thus, financial efficiency examines loan efficiency at the micro level. However, this restrictive definition of financial efficiency would not be a valid efficiency criterion if loans were being used as an instrument for delivering the optimal subsidy.

2.3.1. The Cost of Administering the Schemes

- To evaluate the relative financial efficiency of loan and grant systems, we should examine the variations in the cost of administering both systems. It is argued that the cost of administering a loan scheme is more expensive compared to grants (Barr, 1989). This is because once the grants are given, students will only need to complete their courses on time and the system incurs no further costs. However, for a loan scheme, there are initial processing costs, overall maintenance costs and collection costs (Albrecht & Ziderman, 1991). The start-up costs include administrative expenses and disbursements to students before the first borrowers enter the repayment period (Carlson, 1992). Mortgage loans, for example, have a high public-sector cost which does not enable the system to expand. They are inflexible and administratively costly (Barr, 1989). Thus, critics and opponents of student loans emphasise the administrative problems that can arise, and argue that loan schemes may prove unworkable and thus costly to administer, especially when graduates intend to emigrate. It is impractical to enforce collection on the basis of foreign earnings and therefore there will be a loss to the country financially (Atkinson, 1983).However, the extra administrative cost of loans should not be overstated; developed economies have well-established capital markets geared to administer loans to individuals which would minimise the marginal cost of administration (Lewis, 1980). The administrative cost also depends on the type of loans scheme introduced. The National Insurance Contribution Scheme proposed by (Barr 1989; Barr, 1990; Barden, Barr and Higginson, 1991, Barr and Crawford, 1996) for England demonstrates that the administrative cost will be small since the Department of Social Security needs only to switch on the additional National Insurance contributions. The Department of Social Security can switch it off years later after the repayments for individuals have settled. The cost of administration can be kept minimal through computerisation whereby data can be updated and co-ordinated easily. The collection of loans-repayments could be done efficiently through the taxation department due to large economies of scales (Albrecht and Ziderman, 1991). Recent work also shows that the NIC scheme has a faster repayment stream (Barr and Falkingham, 1993; Harding, 1993, provides the similar case of the Australian system) than the loan scheme in England and Wales. Hence, we should not introduce the types of loan schemes where the costs of administration are excessive when compared to the benefits because of heavy subsidy, in small-scale operation, and poor communications to the recipients. The introduction of such schemes cannot be justified on the grounds that they reduce public spending. If the cost of collection is more than the cost of administering the loans, it is better for the government to introduce or continue grants. In contrast, a grant scheme that attempts to cover full costs is expensive. The British taxpayer used to make one of the largest contributions for student maintenance in comparison to other countries. This helped to keep the higher education system in Britain before 1990 small, since for taxpayers the cost of expanding the system was high (Barr, 1989).

2.3.2. Repayment

- The cost-recovery of the loans would also depend on how they are repaid. One important factor affecting the effectiveness of loan schemes is the relationship between the loans and graduates' future income. The larger the income relative to the loan, the more likely are borrowers to have funds for full repayment, and the better the overall rate of cost -recovery (Mingat and Tan,1986).Hence, the amount of the loans which can be recovered depends on the terms of repayment - the length of repayment and the present income that graduates allocate to repay the loans. The government may prefer to keep the repayment period short so that the loan scheme can become self-financing quickly. But the graduates want it to be long. This creates tensions between the students and the government. One way to relieve this tension is that the government could sell the debt (loans borrowed by students) to the private sector through securitisation (Williams 1998). The private market would be prepared to buy £1 billion of student debt for about £850 million. However, this is not a magic solution as the private sector would simply expect the government to meet the cost of the risk element (£150 million). Also, tension may also be created between the private sector and the students. Nevertheless, the privatisation of loans would produce immediate savings in public spending of that amount (£850 million, in the example above) per year. Thus, the financial efficiency of any loan scheme will depend centrally on the loan-recovery ratio - the extent to which the loan is repaid in full (Albrecht & Adrian Ziderman, 1989). What governments lend out to students and what is returned in repayments would indicate the loan efficiency. The loan programme would be inefficient if what the government lends out could not be recovered almost entirely.

2.3.3. The Grace Period, Interest Rate, and Defaults

- Usually, a grace period is given for graduates who could not find jobs soon after their graduations. The longer the grace period, the slower will be the start of loan repayment and the more loans will be impaired being fully self-financing quickly. The rate of interest charged to the loans is also important, as it would determine both the length of repayment and the recipients’ ability to pay. If the interest charged is unsubsidised, this may discourage students from disadvantaged background to borrow and hence would be inequitable. Loans may be inefficient if high interest causes high default rates, which would be very costly to the taxpayers.

2.4. Effects of loans to Institutional Efficiency

- The introduction of a loan scheme linked with higher levels of fees may increase the efficiency of universities who are forced to compete for students to reduce costs, improve the quality of education and upgrade subsequent marketability of skills provided. It is argued that universities will seek more efficient allocations and utilisation of resources such as physical plant, and academic staff (Williams, 1987). Institutions will be forced to become consumer-oriented in the competition for students (Blaug, 1990). Students will be reminded about the private cost of their education, which in turn induces them to maximise the educational benefits of higher education (Blaug, 1990). This will indeed generate a higher economic value for higher education (Ziderman & Albrecht, 1995). However, the above view is not completely correct because political factors may influence student enrolments to universities. In the case of Malaysia, a quota system is used to determine student enrolments into public universities, in which 55 per cent of university places are reserved for bumiputera. In this situation, the introduction of loan schemes may not have a strong effect on the competitiveness of universities, as the places offered in the universities are being regulated.It is argued that with the introduction of a loan scheme, universities will be forced to respond to students' choices or demand as universities would offer type of courses demanded in the labour market (reflecting relative earnings and shortages in the labour market (Ziderman & Albrecht, 1995). This would lead to exchange efficiency in terms of ensuring that the output they produce will match with the demands of the society (Mace, 1993), and production efficiency that will minimise the cost per student. Students are given the power to penalise inefficient producers (universities, colleges) by withdrawing (Atkinson, 1983) if the latter cannot meet the students’ demands. Thus, "if institutions derived their finance directly from the customer, they would have stronger incentives to innovate and put on courses relevant to the perceived needs of the students"(Atkinson, 1983 P 109).However, this may not be necessarily the case, because of the imperfect nature of the markets. Information obtained by students regarding labour market conditions may be distorted and inaccurate. Moreover, institutions may sell diplomas or degrees rather than education in situations where the labour market rewards degrees rather than skills (Ziderman & Albrecht, 1995). Nevertheless, production efficiency may result if students pay part of the institutional costs of universities. The impact of this depends on the sources of a university’s income. If the university's income derives entirely from fees paid by students with borrowed money in relation to other sources of income, the impact on the institution will be greater. Thus, the power of students to force the university to respond to students' choices depends on the size of loans.

2.5. The Cost of Contraction/Expansion of the University

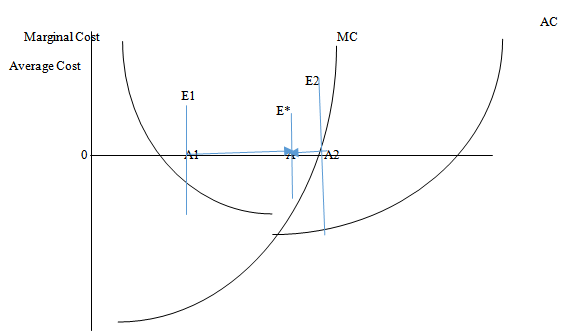

- The introduction of a loan scheme may affect the number of students enrolling, depending on the types of loans and the context where loans are introduced. If a mortgage type of loans is used to replace existing generous grants, enrolment may contract. In contrast, if an income-contingent loan is introduced where scholarships or grants are limited, enrolment of university students may expand. The contraction/expansion of student numbers will affect the marginal and average costs of the operation of universities. If the average costs are minimised already, any contraction/expansion will cause diseconomies, giving rise to production inefficiency. Figure 1 shows that the point E* is optimal where Marginal Cost (MC) equates Average Cost (AC) with enrolment of OA. But, at E1 and E2, diseconomies occur, where enrolments are at A1 and A2 respectively.At OA1, there is room to increase the enrolment to OA by giving generous grants. At OA2, replacing grants with mortgage-type of loans or even income-contingent loan can reduce the students' enrolment. However, the government must also consider whether loans are the best way of achieving contractions, since lowering the benefits through increasing the tax rate on graduate incomes can also do this. If contraction is not wanted, the government must consider whether it is worth offsetting the effect of loans on student numbers by increasing the subsidy in some manner or even by subsidising the loan programme (Verry, 1977).We can also regard education to some degree as a jointly supplied service (Monk, 1990) This means that the education service is equally and simultaneously available to all individuals. Thus, the consumption of a jointly supplied good (lecture) by one individual does not affect the ability of others to simultaneously consume the same good (lecture). The elements of jointness in education are important because the producer (University) can reallocate the resources efficiently so that price equates marginal cost. If there is shortfall of demand, grants/scholarships can be provided to increase the enrolment to achieve the optimal numbers and vice–versa. However, jointness in education may be disputed. As more students attend a lecture, their learning ability may decline because of the crowding effect. The use of devices such as TV may change the instructor’s style of presentation, which may affect the learning process of certain students. Moreover, an additional unprepared student could seriously disrupt a seminar. Also, free riding problem could arise, because individuals may conceal their preferences for education, leading to inefficiencies as a result of unstable equilibrium (Monk, 1990).

| Figure 1. Contraction and Expansion of Universities |

2.6. Optimal Subsidy

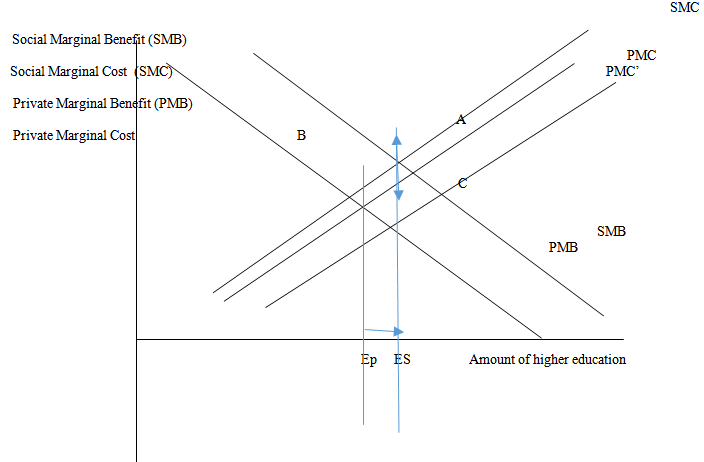

- In examining the loans and the scholarship systems practised in Malaysia, I shall consider the question: “Can optimal subsidy be achieved?” Higher education should be expanded up to the point where its marginal social cost equates marginal social benefit (Verry, 1977). At this point the society has the optimal number of students (Mace, 1987). But, if higher education were expanded further, the costs of this expansion would outweigh the benefits. If expansion has not been carried to this point, potential investments (in expansion) for which benefits exceed costs have been ignored (Verry,1977, p61; Mace, 1987).However, private decisions may fail to produce the correct amount of education, because any rational individual will only invest in education where his/her private marginal cost (PMC) equates with their private marginal benefits (PMB). Thus, individual decisions will tend to produce either too much or too little education relative to the socially desirable amount Verry, 1977, p61). Figure 2 shows how private and social marginal costs and benefits vary with the amounts of higher education undertaken.The figure can either refer to an individual or to the higher education sector (Verry, 1977). Private costs and benefits refer to those costs and benefits that would be received by the individual if there were no subsidisation of higher education. Social costs and benefits include not only the private costs and benefits but also include any costs incurred by the society as a whole, and any benefits received by the society. All costs and benefits are in present-value terms.An individual will choose an amount of higher education, where PMC equates PMB, after doing a private cost-benefit calculation. But, the socially optimal amount of higher education is Es, where social marginal cost (SMC) equates social marginal benefits (SMB). So the individual has chosen fewer years of higher education than are socially desirable. In order to ensure that this individual, and others like him/her, does not under-invest in higher education, the government should subsidise him/her by either giving grant or exempting students from paying full fees. The new PMC, that is PMC’ will equate PMB, which also equates with the socially optimal amount of education. The optimal subsidy equals to "s" or BC as shown in figure 2.2. Hence, (EsA-EsC)-(EsA-EsB) or (SMB-PMB)-(SMC - PMC) (Verry, 1977, p62)Conversely, if private investment in education exceeds the social optimum for education, an unsubsidised loan scheme can be introduced to increase the private marginal cost, thereby decreasing the student enrolment until the optimal subsidy is reached again. The increase in cost is equivalent to the interest paid according to the loan scheme.

| Figure 2. The Optimal Subsidy (Verry, 1977, p 61) |

3. Conclusions

- This paper has explored and evaluated some economic arguments on who should pay for higher education and how should they pay. Budgetary constraint as a result of expansion in higher education has pushed governments to call for a greater private share in financing higher education. The efficiency argument on externalities and imperfections in the capital and insurance markets may partially hold true for public subsidisation. However, it is a political decision through electoral support that warrants public subsidisation. In the case of Malaysia, the quota system with the political wills underpin the arguments to answer the open question, “loans or grants” as mechanism of financing higher education (Lau, 2001).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I would like to acknowledge the fruitful comment of Prof. Dr. Ahmad Othman of University College of Technology Sarawak, enabling me to submit this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML