-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2015; 5(2): 112-118

doi:10.5923/c.economics.201501.11

Understanding Cultural Differences in Ethnic Employees’ Work Values: A Literature Review

Daria Gom, Mary Monica Jiony, Geoffrey Harvey Tanakinjal, Ruth S. Siganul

Faculty of International Finance, Universiti Malaysia Sabah

Correspondence to: Daria Gom, Faculty of International Finance, Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Work values are very much influenced by employees’ cultural values and traits. For this study, a qualitative approach on past research and literature was employed. By exploring recent cross cultural research in Malaysia, this paper provides a critical review on the cultural differences of ethnic groups in Malaysia, specifically among the Sabah ethnics employees working in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Malaysia is a multi-cultural country and each ethnic group may not share the same cultural values due to its distinct separate identities and cultures. This study also discusses the findings of researchers on the differences of Malaysian and western work values and their underlying assumptions. In addition, this review hopes to enhance further knowledge and understanding on Sabah Borneo ethnic cultural values and behavior in the workplace for effective management of ethnic diverse employees in pursuit of organizational success.

Keywords: Cultural differences, Ethnic employees, Work values, Sabah Borneo, Malaysia

Cite this paper: Daria Gom, Mary Monica Jiony, Geoffrey Harvey Tanakinjal, Ruth S. Siganul, Understanding Cultural Differences in Ethnic Employees’ Work Values: A Literature Review, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 112-118. doi: 10.5923/c.economics.201501.11.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A large and growing body of research has investigated the impact of culture on the application of management theories and practices in organizations (e.g. Andreassi, Lawter, Brockerhoff & Rutigliana, 2014; Ting & Ying, 2013; Liu, 2012; Selvarajah & Meyer, 2008; Matic, 2008; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Asma, 2001 and Trompenaars, 1994). Hofstede (1980) discovered that management theories developed in one country may not be applicable in other countries due to cultural differences. Similarly, Trompenaars (1994) found that some western management theories and practices such as management by objective and just in time practices have failed to produce results in different cultures and ethnic groups. More recently, attention has focused on the important question whether Western management practices can be used as effectively with employees in Asia and whether the application of Western management principles affects satisfaction in non-Western countries (Andreassi et al. 2014). Asma (2001) affirmed that attempts to bring in western management principles and techniques in Malaysia may not go down well with the Malaysian workforce as they were brought up with unique cultural values that influence behavior in the workplace. These values conflicts with the western management practices that may result in miscommunication and misunderstandings (Trompenaars,1994) resulting in poor work performance. Most Malaysians researchers contended that although western cross cultural and management theories explained the behavior of the Malaysians in the workplace, but it lacks the richness of the relationships within an ethnic group and between cultural groups (Fontaine et al, 2002; Asma, 2001, 1992). It is evident that Malaysia is a multi-cultural country and each ethnic group do not share the same cultural values. Several researchers (for example, Thien & Razak, 2014 and Fontaine, 2002) reported that although there are similarities in work-related cultural values of the ethnics in Malaysia but they have significant differences between the ethnic groups due to distinct cultural and religious heritages. The majority of past Malaysian research was primarily concentrated on comparing the cultural values and behavior of Malays, Chinese and Indians ethnicities in the workplace (Thien et al, 2014; Ting & Ying 2013; Liu, 2012; Razak, Darmawan & Keeves, 2010; Selvarajah et al, 2008; Rashid & Ibrahim, 2008; Fontaine & Richardson, 2005; Asma, 2001). Recent literature revealed a growing interest in ethnics' cultural values, particularly in the context of ethnic groups in Peninsular Malaysia, however, there is a significant deficiency of literature in the study of ethnic groups in Sabah, the second biggest state in Malaysia. Budin and Wafa (2013) also noted that there have been no studies done yet related to Sabah ethnic culture and its impact in the workplace. This knowledge gap has created a void of information to guide further research in understanding the effective management of Sabah ethnic employees in organizations.For this study, a qualitative approach on past research and literature was employed. By exploring recent cross cultural research in Malaysia, this paper provides a critical review on the cultural differences of ethnic groups in Malaysia, specifically among the Sabah ethnics employees working in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. This study is organized into several sections. Firstly, we provide a brief overview of the culture and work values of the Malaysian ethnics and a short description of Sabah’s three major ethnic groups. Next, we review findings on Malaysian and western management practices and the cultural similarities and differences between the three major ethnic groups. The review concludes with its research limitations and suggestions for future studies.

2. Culture and Work Values

- Culture is important in business organizations as business interfaces with people: as customers, employees, suppliers or stakeholders (Jones, 2007). Past research revealed numerous definitions of culture, and each claiming to have a meaningful understanding of the term. Hofstede (2001) refers culture as the collective programming of the mind that need to be unlearned, learned and relearned. Asma (1992) presents an interesting definition of culture “as a shared and commonly held body of general beliefs and value which define the ‘shoulds’ and the ‘oughts’ of life and were instilled in early childhood”. Similarly, House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfmann & Gupta (2004) states that “Culture is defined as shared motives, values, beliefs, identities, and interpretations or meanings of significant events that result from common experiences of members of collectives that are transmitted across generation”.Based on the definitions above, values represent the core element of culture. Cultural values refer to the shared values that are unique amongst communities and these differences between cultures resulted from underlying value systems that cause communities to behave differently in similar situations (Cateora, Gilly & Graham, 2011). Values are the preference of certain states of affairs over another; a society’s ideas about what is good or bad or wrong (Deresky, 2014). Hofstede (2007) found that each individual carries with them values that are learned in early childhood and asserts itself in the culture. Determining the work values of a culture is important because of the differences in values and beliefs. Cultural differences in work values can be used to explain differences in individual performance and predict job satisfaction (Matic, 2008). Locke (1976) defined work values as “what a person consciously or subconsciously desires, wants or seeks to attain related to his/her individual and collective work activities”. Similarly, Chen, (2008) described work values as to the underlying preferences and opinions that should be met in people’s career choice that can result in job satisfaction. The relationship between values and culture has been studied by many researchers (e.g. Soon, 2013; Fontaine & Richardson, 2005; Hofstede, 1991, Trompenaars, 1994, Asma, 1992, Schwartz, 1999) using various cultural frameworks such as Hofstede cultural framework and Schwartz (1999) cultural values orientation. These theories stated that national cultural values relate to workplace behaviors, attitudes and other organizational outcomes (e.g., Hofstede, 1980; Trompenaars, 1994; Schwartz, 1994; Ronen and Shenkar, 1985). Among the numerous cross-cultural studies conducted, Hofstede’s framework on the cultural dimensions is the most cited and empirically developed and is still considered as the most robust measure of culture (Yoo & Donthu, 2011) despite criticisms of its construct and application on multicultural countries like Malaysia.

3. Sabah Ethnic Groups

- Sabah is located in the northern region of Borneo Island, which borders East Kalimantan of Indonesia and Sarawak of Malaysia. Malaysia is a multiracial and multiethnic country with a diverse population of 29.9 million. Sabah, the second largest state has 3.49 million and is the second most populous state after Selangor (Department of Statistics, Malaysia 2013). Based on the population estimates (Department of Statistic, Malaysia 2014), Kadazandusun is the largest ethnic group constituting 17.6 % of the total population, followed by Bajau 14.0%, Malay 7.4%, Murut 3.2% and other Bumiputra 20.3% (Department of Statistics, Malaysia 2013). The culture of these ethnic groups has seen changes from British colonization in 1881, through the Japanese occupation in World War 2 to the modernization and globalization influences (Rouass & Waller, 2011). Human’s relationship with nature, environment, people and God (Asma & Koh, 2009) is observed in the ethnic’s traditional rituals and customs and has a deep influence over their culture. Their traditional beliefs and values were gradually replaced by modern religions, modern lifestyle, beliefs and values. There are officially 32 recognized ethnic groups in Sabah, (http://www.sta.my/index.cfm). It is a common knowledge that regardless of the ethnic’s diversity in Sabah, the people live together harmoniously while at the same time preserving their respective cultures, traditions and customs. For the purpose of this paper, we will describe the three major ethnic groups – Kadazandusun, Bajau and Malay.

3.1. Kadazandusun

- Kadazandusun (KD) is a label coined from Kadazan and Dusun ethnics to unite these ethnic groups under one common name. This ethnic group is the largest indigenous group in Sabah and were traditionally paddy farmers and animism in faith. Its religious activities focused on maintaining a balance of harmony between man and environment so as to bring good harvest of rice, being the staple food of the indigenous people (Regis & Lasimbang, n.d.). Today, due to modernization and change in religiosity, most of these rituals were no longer observe, but remains as a symbol of culture. For example, the Kaamatan or Harvest Festival was traditionally observed to appease the spirit of paddy and is now celebrated annually as a symbol of the KD culture.

3.2. Bajau

- The word Bajau is a collective term to describe a closely related indigenous group i.e. Ubian, Bannaran and Sama. The second largest indigenous group, the Bajau form two distinctive groups based on geographical location – the east coast and west coast. They traditionally lived in the coastal areas and depended on fishing and related economic activities as their means of livelihood. Many of them are predominantly Muslims. The Bajaus used to barter trade their products with the KD in exchange for rice. This exchange also extended to other objects, ideas and concepts as evidenced in their culture, customs and practices (Regis et al, n.d.).

3.3. Malay

- The Malaysian federal constitution defined Malays as a group that speaks Malay, observes Malay customs and are Muslims. By virtue of this qualification, this has increased the number in this category. In Sabah, the Malays refers to the Brunei Malays and other kindred groups like the Kedayans who prefers to be classified as Malays and were broadly classified under this group (Regis et al, n.d.). Brunei Malays occupies the south west coast of Sabah and are predominantly Muslims. Religion and kinship are the guiding principles that influence their behavior, customs, practices and relationship (Regis et al, n.d.).

4. Malaysian Management Practices and Sabah Ethnics Cultural Values

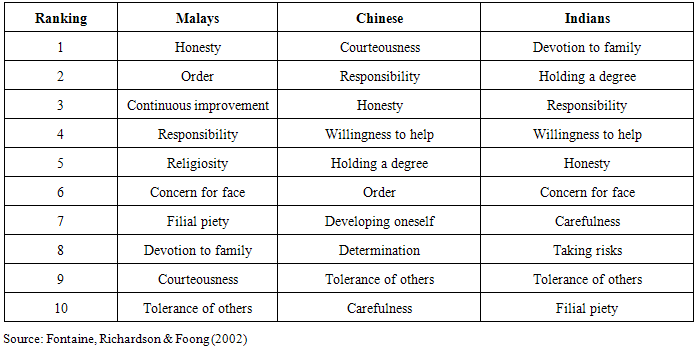

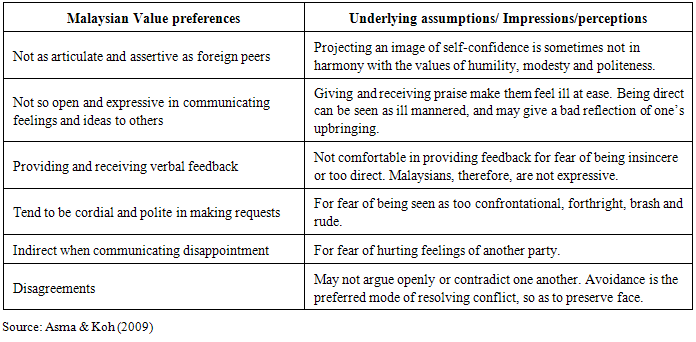

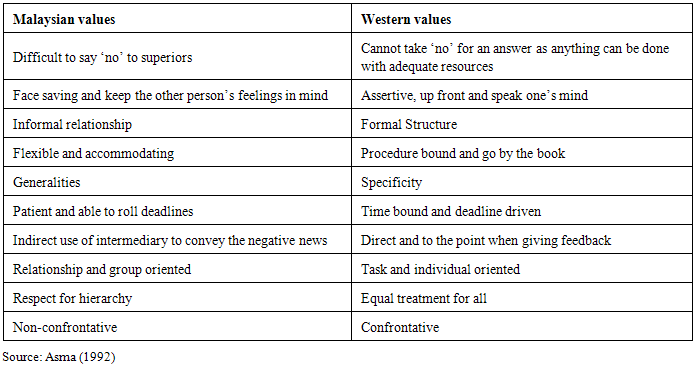

- Management in Malaysia is much influenced by the western management techniques such as those related to teamwork, counselling, performance feedback, negotiation, communication and leadership (Asma, 2001). Past research findings show that attempts to import western management practices without considering the host country’s culture leads to the frequent failure of these practices (Asma, 2001, Hofstede, 1980). In addition to our colonial heritage, foreign investment and industrialization have significantly influenced the traditional business management, which is associated with the westernization of management practices (Kennedy, 2002). However, despite this, the core cultural values of the ethnic groups that serve to create cultural differences remains (Asma, 2001, Kennedy, 2002). Sidhu (2007) also agrees that over the last several years, Malaysian management have been exposed to a number of western theories and practices which may not be appropriate for the Malaysian employees. Asma (2001) observed that these unique cultural values are revered by all Malaysian ethnics and form the basis of shared rituals which are frequently strengthened within family members and significant elders. From her research, she has identified some underlying values that characterize the Malaysian workforce in general, such as non-assertiveness, preserving face, loyalty, respect for authority, collectivism (“we” orientation), cooperation, harmony and non-aggressive, trust, relationship building and respect for differences. These values diverge with that of westerners, that emphasized on assertiveness, independence, aggressiveness and competitiveness. Employers in Malaysia should be culturally sensitive of the differences and any application of western management techniques need to be adapted to suit the Malaysian cultural context as echoed by some researchers (Liu, 2012; Selvarajah et al, 2008; Asma, 2001; Kennedy, 2002). Sabah ethnic groups are well known for their unique and rich cultural values that distinguish them from other ethnics in terms of language, dressing, lifestyle, food, rites, customs, beliefs and values. These cultural variables were traditionally passed down orally (as most of them were not educated in the olden days) through socialization and cognitive processes (Regis et al, n.d.). The transmission of culture usually begins at family, nuclear and communities’ level, taking the form of religious beliefs, music, songs and dance. Traditionally, women folks were known to be submissive and are mostly involved in domestic and religious activities. However, this role has changed with female participation in the workforce since 1970 (Kennedy, 2002) and legislation on gender equality. It was expected that this will affect women’s attitudes and values and promote gender equality, but, this is not to be the case for the female ethnics in Sabah (Budin et al, 2013) where the values across the three ethnic cultures have not changed significantly. In contrast to the findings by GLOBE gender egalitarianism scale in Malaysia, the rating was above the median scale of the ‘as-is’ dimension suggesting gender equity (Kennedy, 2002). Kennedy, 2002 observed that women are yet to attain advancement in the political, private and government sectors as gender issues continue to exist in the society. Lifestyle and behavior of the respective ethnic groups are guided by a set of value system based on moral and religious beliefs, for example the value system of the Kadazandusuns known as ‘adat’ (Asgaard, 2002). Similarly, the Malays have their ‘Budi’ principles, the Chinese based on Confucian teachings and the Indians ‘Dharma’ (justice and ethical conduct) and reincarnation (Selvarajah et al., 2008; Asma et al., 2009; Storz, 1999).Table 1 shows the ten most important values of Malays, Chinese and Indians from a study conducted by Fontaine, Richardson & Foong (2002). It can be seen from the table that the three ethnic groups may share similar values but differs in priority. For example, ‘honesty’ is ranked as most important for the Malays whereas it is ranked third and fifth by the Chinese and Indians respectively. On the other hand, there are some values, for example ‘religiosity’ only appears for the Malays, ‘developing oneself’ for the Chinese and for the Indians ‘taking risks’. This clearly shows that there are significant cultural differences between the ethnic groups due to the preservation of separate identities and cultures (Thien et al. 2014). Based on personal observation, some of these values may also be found in Sabah ethnics as well, however the order of importance may vary. A study conducted by Budin et al (2013) among the Sabah ethnic employees revealed similar cultural values but differed in terms of degree towards the four cultural dimensions, namely power distance, uncertainty avoidance, collectivism / individualism and masculinity/femininity. For example, the Malays, scored higher in power distance compared with the other ethnics and this can be attributed to the considerable importance placed on status and hierarchical order (Kennedy, 2002; Asma et al, 2009). GLOBE study (initiated in 1991) also reported that Malaysian employees are collectivism in nature, emphasizes on the importance of relationships, respects of elders and authorities, group work and face saving (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005; Kennedy, 2002).

|

|

|

5. Conclusions and Future Studies

- Our study was based on understanding the cultural differences in Malaysian ethnics’ work values that impact western management techniques and practices. We had searched the literature review extensively based on empirical studies and reviews to support the similarities and differences of cultural values of Malaysian ethnics, in relation to Sabah Borneo ethnic diverse employees. This study has given us some understanding of Malaysian ethnics values specifically the Malays, Chinese, and Indians. It can be observed that Sabah ethnics namely the KD, Bajau and Malays may share some of the values, but the priority of importance may differ. The results of this study also implied that there exist significant cultural differences between the three ethnic groups due to the distinct and separate culture and identity. However, it is to be noted that these findings and observations are not conclusive as a further research need to be conducted for it to be definitive.One of the limitations of the study is the lack of literature on Sabah ethnic’s cultural values. Most of the literatures referred were studies made in Peninsula Malaysia. The findings by Thien et al. (2014), Fontaine, (2002) and Asma (2001) showed significant cultural differences between the Malaysian ethnic groups. In addition, the values that they may have in common may differ in terms of importance or priority. It can be deduced that the Sabah ethnics’ cultural values may have significant differences with that of the Malays, Chinese, and Indians in the Peninsula Malaysia. Nonetheless, it is recommended to conduct future research on the cultural differences between Sabah ethnic groups, specifically focus on work related cultural values for better understanding of ethnic cultures in Malaysia.Another interesting direction for future research is how modernization/globalization and technology affect the value systems within the Sabah ethnic’s culture that may lead to changes in underlying work values. Studies made by Budin et al. (2013) on Sabah ethnics, Asma et al. (2009) and Ting et al. (2013) on Peninsula Malaysia ethnics reveals some changes and shifts in the cultural practices and values of Malaysian ethnics over time probably due to modernization and globalization.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML