-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2013; 3(C): 87-93

doi:10.5923/c.economics.201301.15

Developing a Perceived Audit Independence Rating Index for Nigerian Auditors: A Proposed Framework

Fatima Alfa Tahir, Zaimah Bt Zainol Ariffin, Kamil MD Idris

School of Accounting, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 UUM Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Fatima Alfa Tahir, School of Accounting, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010 UUM Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

There has been much public, professional, regulatory and scholarly concern about auditor independence in recent times. This is because of the high incidence of corporate collapses and the role of the auditor as a watchdog. Although auditor independence depends on both fact and appearances, researchers and regulators focus on examining appearances of independence because of the inability to observe the auditors state of mind. These perceptions inform the confidence reposed on financial statements and consequently, efficiency of capital markets. Inconsistencies in measuring auditor independence by using diverse proxies have resulted in conflicting findings in evaluating the constituents of auditor independence. This paper proposes that auditor independence as defined by fact and appearances can and should be measured by regulatory and informed stakeholders in order to determine the confidence to be reposed on financial reports and audit quality. This can be achieved by assessing user perceptions and developing a perceived auditor independence rating (PAI) index based on identified constituents. The paper also proposes that the acceptability of the rating index to stakeholders can be evaluated to assess how stakeholders rate auditors’ independence. Nine propositions are made to support and examine the proposed framework.

Keywords: Independence of mind, Independence in appearance, Objectivity, Integrity, Professional skepticism

Cite this paper: Fatima Alfa Tahir, Zaimah Bt Zainol Ariffin, Kamil MD Idris, Developing a Perceived Audit Independence Rating Index for Nigerian Auditors: A Proposed Framework, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 3 No. C, 2013, pp. 87-93. doi: 10.5923/c.economics.201301.15.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Auditor Independence (AI) has historically been described as the cornerstone of auditing which is fundamental in adding value to corporate financial reporting[1],[2]. “Reference[3] defined audit quality as a function of the auditor’s competence and independence”. While professional training and qualification takes care of an auditor’s competence, independence is a more subjective term which deals with the ability of the auditor to maintain and be seen to maintain objectivity, integrity and professional skepticism. The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) has identified two types of independence; independence in fact (IIF) and independence in appearance (IIA) which auditors are expected to maintain when carrying out audit assignments. IIF is the state of mind with which the auditor approaches the audit work as characterized by objective, integrity and professional skepticism. IIA refers to a situation whereby the auditor presents himself in such a way as to avoid insinuation from informed third parties having relevant knowledge of facts to conclude that the auditor is client-dependent[4]. This means that the independent auditor should be objective, unbiased, have integrity and professional skepticism and should always be seen to be independent by all stakeholders. Given the crucial significance of this concept to audit quality, the need for measurement in order to monitor and control AI becomes paramount. The Independence Standards Board[28] defines this independence risk as the risk that an auditor will make biased judgments about a client’s financial statements arising from inability to effectively curtail threats. There are many studies examining the determinants of AI from archival and perceptual perspectives using economic modeling, experimental and cross sectional surveys to evaluate user perceptions on factors influencing AI. Most of the studies focus on establishing dependence relationships among various factors and proxies of AI. The perceptual studies[5],[6],[7] generally focus on investigating the views of various users on limited factors influencing AI such as non-audit services (NAS), economic dependence, auditor size, client size, audit committee, auditor tenure and competition in the audit market using various proxies. However, few studies have considered empirically measuring AI despite calls for developing such a measure[8]. Presently, there is no composite measure that can be used to measure auditor’s independence by informed stakeholders. In filling this vacuum, the main objective of this study is to contribute to the AI literature by gaining an understanding of the concept of AI and its constituents and proposing a measurement of AI as perceived by the Nigerian stakeholders. The proposed rating index is directed at determining stakeholders’ perceptions of auditors’ independence. This will be very relevant to the auditors in improving appearances of independence and providing a signal of high integrity AI to stakeholders and capital markets. The PAI rating index will also provide regulatory authorities a means of measuring and monitoring perceived AI levels because perceptions of stakeholders reflect the confidence they repose on audit reports and hence audit quality. Shareholders and investors will also be able to evaluate auditors and make informed investment decisions based on empirical assessment. The framework for the study will be based on prior interdependence studies and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) conceptual framework on AI. Furthermore, other components identified from the Certified Public Accountants (CPA) characteristic instrument will also been included to evaluate informed stakeholders perceptions of auditor objectivity. The remaining part of the paper reviews prior research on determinants and measurement of AI, based on which a framework for developing the PAI rating index is proposed.

2. Literature Review

- AI has been a fundamental concept underlying audit stewardship which emphasizes the need for the auditor to act with integrity, objectivity, impartiality and professional skepticism in the conduct of an audit engagement[9]. It has been argued[10] that lack of auditor independence was an underpinning factor of the corporate collapses in the United States, Australia and Italy. However, AI problems have also been posited to originate from the ambiguity associated with who the ultimate employer of the auditor is[11], Psychological, economic and social pressures[12],[13] the party responsible for hiring, remunerating and terminating audit engagements[14] and flexibility offered by accounting standards[5],[15] which create incentives that may induce auditors to compromise AI. These various perspectives from which AI have been studied have sought to examine the relationship between AI and other factors such as non-audit services (NAS), economic dependence, auditor size, client size, audit committee, auditor tenure, competition in the audit market, audit fees, ethical cognition and moral development and flexibility of regulatory standards using various proxies. The conflicting findings arising there from, in the face of desperate need for scholarly guidance to inform regulatory policies and AI standards present an opportunity to focus on the need to measure AI.There are a few studies which have sought to measure or provide a framework for assessing AI. “Reference[16] developed a framework for evaluating the influence of direct and indirect incentives, situational and mitigating factors on independence risk, and consequently, audit quality”. The framework was however not subjected to empirical testing. Additionally,[17] use the belief function framework to calculate independence risk as a function of incentives, opportunity and auditor integrity. They develop a model of AI risk which supports integrity as the key variable in curtailing independence risk among other mitigating factors such as effective professional standards, auditor incentives and certain client characteristics. Their model however failed to encompass the interactional effects between the variables identified as well as the effects of safeguards, regulations and audit firm policies that also signal reduced independence risk to stakeholders. Another study[18] argues against focusing on AI which depends on relationships and proposes a framework which emphasizes auditor reliability in fact and appearance which is an embodiment of independence, integrity and expertise to attain objectivity. The study presupposes that since total independence is unobtainable given the auditor-client relations, pursuing reliability of financial statements through auditor objectivity as defined by his integrity, expertise and independence is a more realistic target. The study failed to empirically test the proposed model.Similarly,[19] developed the Audit quality model (AUDQUAL) which harmonized audit technical quality with service quality. AI was defined as a percentage of engagement partner’s audit fee control in relation to total fees control. However audit fees may be inadequate to evaluate AI and cover the domains of fact and appearances. AI was also considered a less important audit quality characteristic despite the firm resolve of various Governments and regulatory bodies in regulating and safeguarding this concept. Another qualitative study[20] used six case studies about auditor-client interactions involving significant accounting issues to analyze the audit risk model as supported by the UK independence framework. They find a linkage between audit risk and independence in fact and re-conceptualize the audit risk model to include motivation, independence in fact and competence risks and these were segregated according to firm based and client based risk. Their new AI risk model recognizes total audit risk which results from additional threats as urgency and face saving threats. Intimidation threat was found to be the most frequent threat encountered due to fears of client loss. A more recent study by[21] extended the model by[17] by developing a general framework based on threats and safeguards of AI. The study developed analytical formula for assessing AI risk using the Bayesian and Belief based theories based on six risk factors; three related to threats (incentives, opportunity and attitude) and three others relating to ineffective safeguards to these threats. Though the study operationalized its formulas based on assumptions and used both theories to calculate AI risk, the study called for empirical studies to validate the probability functions, measures, weighting of factors and usefulness of the approaches. The study did not consider perceptions of factual independence nor ascertain the level at which AI becomes acceptable to stakeholders (users and regulators). Researchers and regulatory bodies[22],[8],[23] have often called for the development of more concise structural models or instruments from a sophisticated selection of variables by combining various indicators into a single index score which can be validated. This study proposes to fill this gap and extend prior studies by evaluating the constituents of AI and developing a composite rating index that will provide a measure of AI and evaluate the acceptability of the index by stakeholders.

3. The Proposed PAI Rating Index

- Composite measures are increasingly being used as tools for decision making, policy analysis and public communication because they enhance comparisons of countries, entities or phenomena involving complex and ambiguous issues into simple summary assessments. According to[24] they enable governments to ascertain actual attainments compared to expectations which informs better decisions. There should be a system whereby the regulatory and professional bodies are able to monitor and evaluate adherence to professional codes and standards. One way of achieving this is by evaluating how informed stakeholders rate auditors in the financial reporting process. The importance of audit rating systems has been appreciated by prior literature in various service sectors. For example,[25] found that hotel rating systems enhanced service quality standards in terms of basic facilities, feeding and lodgings. Additionally,[26] also found rating systems provided banks an opportunity to assess credit risk exposures especially during pricing of bonds or loans and enhance management of credit portfolio against perceived threats. In Malaysia, the need to improve accountability of public officers in the management of public funds motivated the National Audit Department (NAD) to introduce the Financial Management Accountability Index (FMAI) in the public sector. The use of this rating system benefits the government, regulatory bodies, users of information and the subjects of ratings themselves by providing a means of measuring, monitoring and improving performances. Furthermore, rating systems can empirically denounce or justify stakeholders’ negative perceptions about accounting problems and audit failures[27]. This buttresses the need for evaluating the perceived AI of Nigerian Auditors.

4. Hypotheses Development

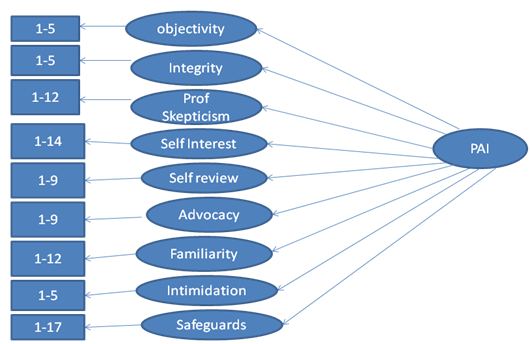

- The[4] requires auditors to be independent in fact and appearance. Independence in fact (mind) is determined by the state of mind which permits the auditor to act with objectivity, integrity and professional skepticism in the conduct of an audit. Because these qualities are fundamental to IIF, the study makes the propositions that:H1a: The PAI index in Nigeria should embody an assess -ment of perceived auditor objectivityH2: The PAI index in Nigeria should embody an assessment of perceived auditor integrityH3: The PAI index in Nigeria should embody an assessment of perceived auditor professional skepticismIndependence in appearance (IIA) on the other hand is concerned about auditors’ ability to avoid circumstances or interests that may make informed users, having knowledge about the facts and safeguards applied, doubt their ability to render objective opinions[4]. According to[28] independence threats represent sources of bias which provide incentives to auditors to compromise their objectivity. These threats result from various circumstances and relationships which put pressure on an auditor’s ability to remain objective in the conduct of an attest function. Such circumstances generally fall under five categories of threats namely self interest threat, self review threat, advocacy threat, familiarity threat and intimidation threat. According to[4] self interest threats result from auditors having stakes or personal interests in their audit client as a result of direct or indirect material financial interest, provision of non-audit services, economic dependence on client, loan to or from client, contingent fees or unpaid fees, business relations with client and prior or potential employment with client. Prior studies show that auditors are more likely to accept client choices, identify with management and become reluctant to criticize client management[29],[30],[31],[32] permit greater earnings management[33] and are negatively perceived by stakeholders[34],[35]. This shows that self interest threats make auditors align their interest with client management instead of protecting other stakeholders’ interests. It then follows that stakeholders are more likely to assess the magnitude of self interest threat when evaluating auditor objectivity. In line with this, it is reasonable to suggest that:H4: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of self interest threats Based on[4], the self review threat arises when auditors are placed in position to review their own work (e.g. by providing joint assurance and certain non-audit services) or were former client employees. Prior studies indicate auditors faced with self review threat were perceived as less independent[36],[37],[6] and put in less effort in reviewing prior work[38]. Furthermore, effective audit committees were less likely to procure NAS from incumbent auditor[39], or outsource internal audit services to incumbent auditors [40]. Put together, the studies suggest that stakeholders are more likely to also examine an auditor’s objectivity when he is placed in position to review his own work. In line with this, the study makes the following proposition:H5: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of self review threats Auditors are exposed to advocacy threats when they promote client interests by performing managerial functions/decision making, litigation services or acting on their client’s behalf in dispute resolution with third parties[4]. Past studies show that advocacy threat undermines auditor independence. For instance, auditors providing litigation support services were more likely to promote their client’s position[41],[29],[42], assist their clients in aggressive tax planning and representations before Tax authorities[37],[43] and sometimes viewed themselves as client advocates and responsible to management[44]. Also, users perceived objectivity to be impaired when auditors advocated for their client management[6]. Taken together, the studies imply that auditors are perceived as biased when they advocate client positions. Since stakeholders consider advocacy as threatening auditor objectivity, they are more likely to consider and assess circumstances that place auditors in advocacy position when rating auditors. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that:H6: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of advocacy threats Familiarity threats arise from having close family ties with client employees, family member in an influential position in client company, influential client officer was a former partner, lengthy audit tenures or accepting gift and hospitality from client[4]. Prior studies indicate that when auditors become too familiar with their clients, they are more likely to accept client accounting choices and identify with their interest[45],[46], exert little effort in audit planning and testing[47],[48], are more likely to be offered and accept jobs with client[49],[50],[51] and more likely to be perceived as biased by users[34],[52]. In addition, close bonds resulting from lengthy tenures were found to be associated with lower audit quality and earnings management[53],[54] and higher equity risk premium demands[55]. Furthermore, users perceive auditors accepting client gifts and hospitality as compromising their objectivity[56],[52]. These results suggest that circumstances engendering familiarity threat are perceived by stakeholders as negatively impacting auditor independence. Hence informed users will be more likely to evaluate the extent of familiarity threats when rating auditors’ independence. It can therefore be proposed that:H7: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of familiarity threatsAccording to[4], intimidation threat result from threatened dismissal or litigation, client pressure to reduce scale of audit work to reduce fees, greater client expertise in matters or partner promotion contingent upon acceptance of client policies[4]. Little scholarly attention has been given to intimidation threats. The studies show a client’s ability to exert pressure on auditor judgment can be linked with its financial condition. For instance, auditors are more likely to acquiesce to bigger clients having strong financial condition than smaller or weaker ones[57],[58]. Further, auditors facing intimidation threat are more likely to be pressured into hasty decisions through bullying into accepting client choices[59] or threatened with auditor change[60],[61]. The risk of client loss has also been significantly associated with independence compromises[62] as auditors’ yield to pressures in order to retain clients. Other studies[63],[37] argue that auditors earning significant tax fees face intimidation threats which make audit managers less likely to confront client management where compensation schemes are tied to client satisfaction which has been found to decline with greater professional skepticism. In line with these studies, stakeholders will perceive a possible impairment of auditor independence due to perceived auditor intimidation where auditors have large influential clients, provide tax services, are faced with likely change or compensated based on client retention. It is therefore reasonable to propose that:H8: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of intimidation threats Safeguards are measures, actions or procedures that can be employed to eliminate or limit threats to acceptable levels that no longer pose threats to auditor objectivity[4]. They include professional, legislative or regulatory safeguards or safeguards within the work environment. In applying safeguards,[4] requires professional accountants to exercise professional judgment by considering what a reasonable and informed third party will conclude after weighing all relevant facts and circumstances available to the professional accountant such as the significance of the threat, nature of engagement and firm structure. Examples include firm quality control procedures, disclosure of fees (NAS and attest) and types of services provided, disciplinary measures, professional and regulatory monitoring, separation of attest and consulting staff, existence of corporate governance mechanisms, independent partner reviews and partner or firm rotation.Prior studies have shown that safeguards mitigate independence threats and enhance PAI[34],[64],[38]. Effective audit committees have also been found to eliminate agency conflicts by demanding higher audit quality[65],[66], purchase fewer NAS from incumbent auditors[39], were less likely to dismiss auditors and safeguarded AI[67]. Positive outcomes from effective oversight included fewer restatements, reduced fraudulent financial reporting and litigations[68],[69] which will translate into enhanced actual and perceived AI. Cooling off (window) period was also found to reduce the threat of revolving door syndrome on auditor objectivity[50]. Quality control and third party reviews also signal a commitment to audit quality[16], improve audit risk assessments[70] and are generally perceived as important in maintaining audit quality[71]. In sum, the conceptual framework and empirical results emphasize the relevance of maintaining adequate safeguards to eliminate or manage threats to acceptable levels to enhance both IIF and IIA. In line with this, the study makes the following propositions:H9: The PAI rating index should embody an assessment of safeguards implementation

4.1. Research Framework

5. Conclusions

- The proposed framework shows PAI can be measured by various variables which can be used to develop an instrument for rating auditors based on stakeholders’ perceptions. This has implications for auditors, regulators and stakeholders. For instance, if auditors know they are assessed by stakeholders, they will improve appearances of independence so that stakeholders have more confidence on their reports. Regulators will also have a performance measure that is evaluated by beneficiaries of audit service which can be used to direct regulatory attention. Stakeholders will thus benefit from improved auditor objectivity which will mitigate agency conflicts.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML